|

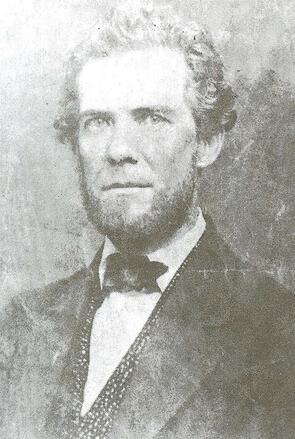

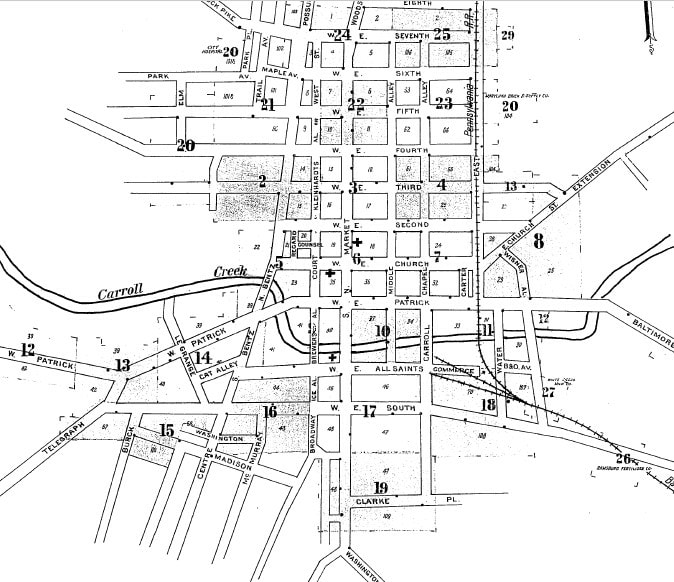

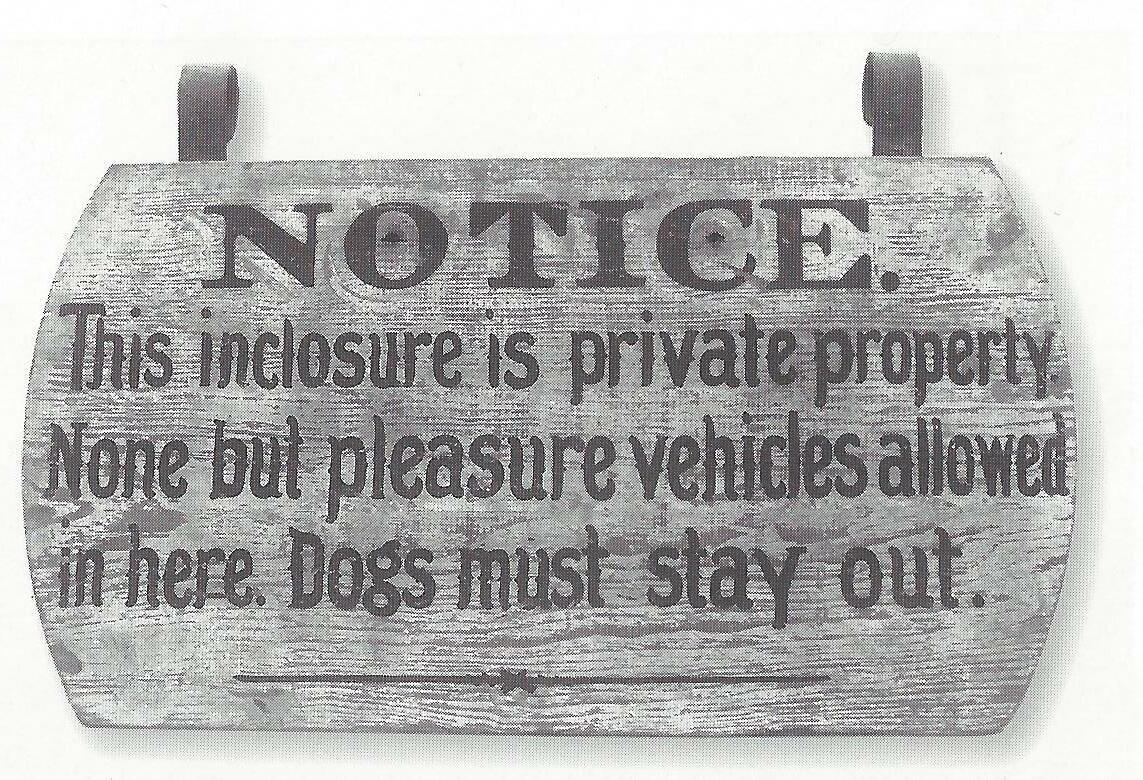

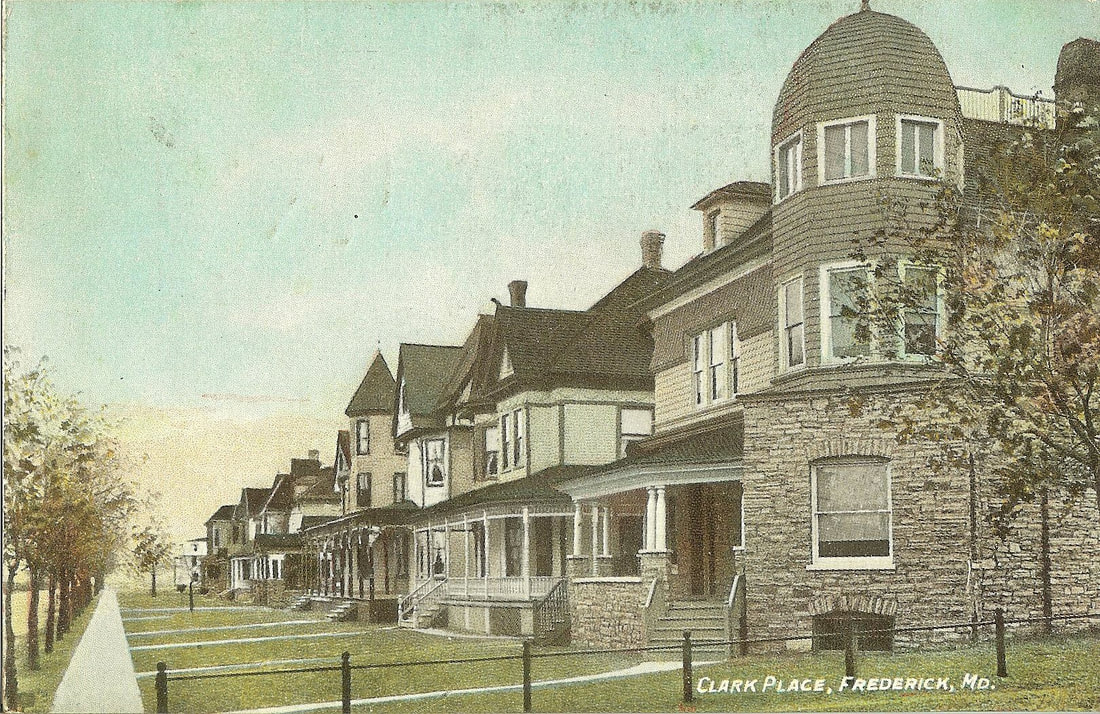

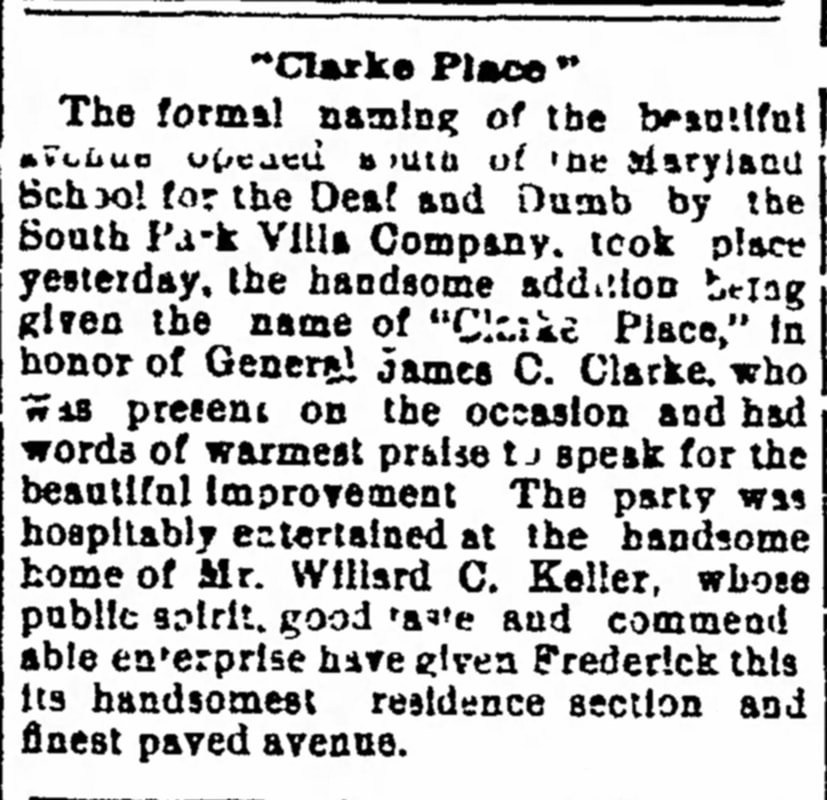

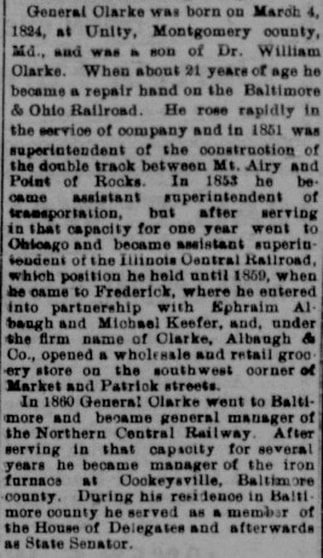

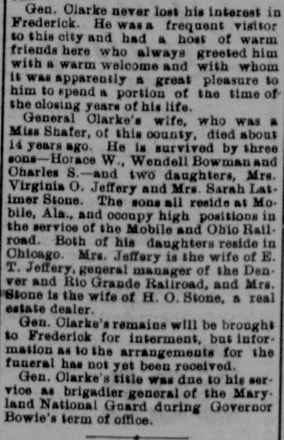

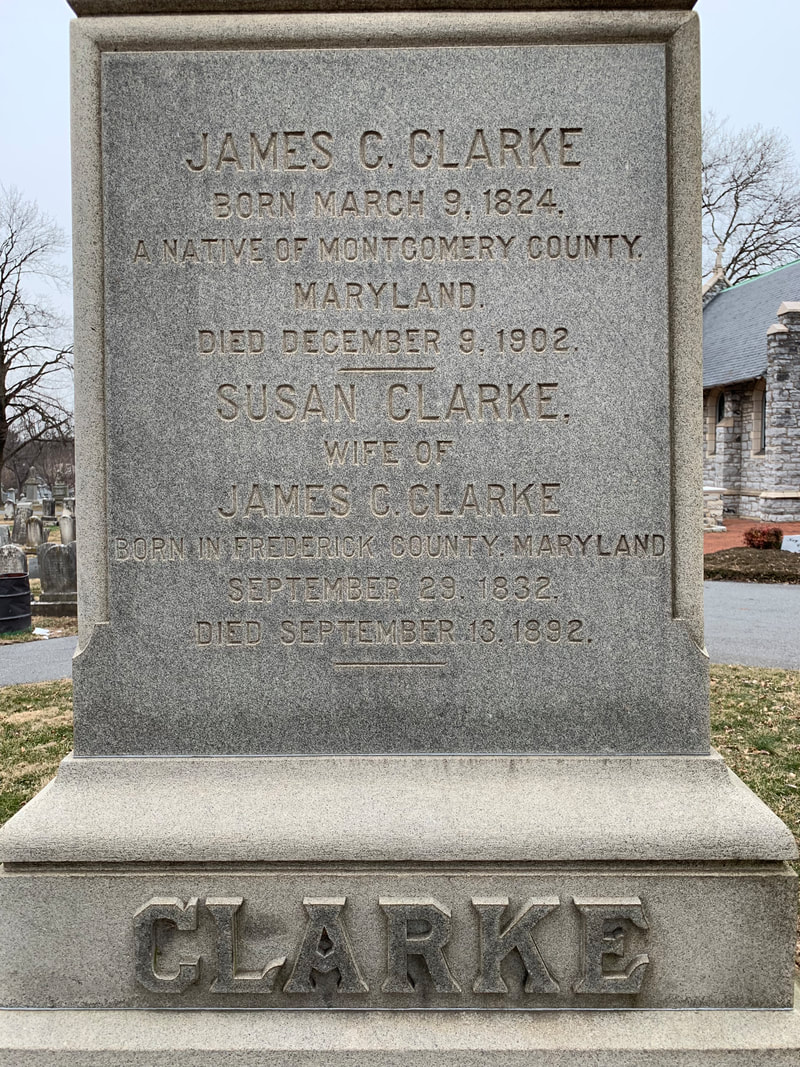

You can’t go anywhere these days and not hear about “walls.” It reminds me of an interesting local history tale that deals with the genesis of Frederick’s first, gated community. Many think this would have to be a more current occurrence, but it happened in the late 1800’s, and apparently was a happenstance created by two key ingredients: milk and cobblestones. The locale was positioned of Frederick’s southern city limits, not far from our cemetery, actually only about a 100 yards north from Mount Olivet’s front gate. Here one can find Clarke Place, a short avenue that connects S. Market St. eastward to S. Carroll Street. Along the way, fine examples of Victorian-era architecture line the south side of the thoroughfare. To the north is the campus of Maryland School for the Deaf, resting atop the footprint of what remains of the Frederick “Hessian” Barracks compound atop aptly named Barracks Hill. A large, farmstead once sat to the south of the school, and was owned by Dr. Bradley Tyler. This eventually came into the possession of Mr. Harry W. Bowers and the South Park Villa Company. Mr. Bowers was a land developer and also a Clerk of the Circuit Court of Frederick County. The South Park Villa Company hired John F. Ramsburg to survey a series of residential building lots on the north boundary of his property in the year 1894.  Former home of Harry and Anna Bowers Former home of Harry and Anna Bowers Mr. Bowers built the first house on the block, a brick structure. Soon others would follow, utilizing some of the most creative designs of the day. Features employed included broad front porches, turret-like towers and gingerbread trim. The vicinity quickly became one of the most exclusive neighborhoods in town. It predated Rockwell Terrace and the major College Park development that would eventually bolster the northwest side of town a few decades later, built adjacent the new campus of Hood College. To add to the grandeur, Clarke Place was one of the only paved secondary roads in town. Of course, we are not talking about the use of macadam here, but rather, cobblestones. Well the old story, whether apocryphal or not, goes that a milk wagon, pulled by horses, traversed Clarke Place to deliver dairy products to customers on the street. More so, the road provided a shorter route for said vendor to make his way back to the milk plant (on the east side of town), without having to backtrack through Frederick’s center city. Apparently more than one neighbor got perturbed with the daily clanking of hoofs upon the cobblestone drive early each morning. And if the milkman was using this as a short-cut, odds are there were plenty more. This quandary eventually led to an iron-clad solution to keep the riff-raff out as rail fencing went up on both ends of Clarke Place. Talk about your “crying over spilt milk! Another interesting anecdote comes from a gentleman named Melvin M. Engle (1903-1984), one-time vice-president of Mount Olivet’s Board of Directors. Mr. Engle grew up on the proverbial “other side of the tracks,” among the many blue-collar families residing in townhouses along S. Market Street. He told our cemetery superintendent, Ron Pearcey, that on more than one occasion, he and his buddies would be playing ball on S. Market and an errand hit, or throw, would put their baseball in the trajectory of Clarke Place and the other side of the railed fence. As one of the lads sheepishly went to retrieve said ball, old Mrs. Anna Bowers, usually parked on her front porch, was already in hot pursuit of the round, stitched and leather-bound intruder. She would lay claim to the ball being on her property, and promptly took it into her home amidst the begging of the boys. This usually put an abrupt end to the sporting forays of the neighborhood children. Just as Clarke Place was imposing to many Frederick residents, old and young, the grave monument and memorial to the street’s namesake is equally awe-inspiring. With no further adieu, let me introduce to you, Gen. James C. Clarke, whose reputation and career seem to be more than fitting to deserve the 30’ obelisk that rests atop his mortal remains, and those of his family.  Gen. James C. Clarke Gen. James C. Clarke James C. Clarke James C. Clarke was a true “rags to riches” success story, rising to the pinnacle of his profession. He was described as “a rough and ready railroader, tall and strong with a can-do attitude—a master storyteller and loved by all.” Clarke was born March 9th, 1824 in Unity, Maryland (within Montgomery County). His parents were Dr. William Clarke and Elizabeth “Betsy” Simpson. James’ father came from Newtownards, Ireland, located in County Down. His mother’s family (the Simpsons) originally came from southern England. Dr. Clarke would gain employment with the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad when it was extending its line into Frederick County in the late 1820’s. Simpson family historian Sharon Chrisafulli paints a colorful picture of the early childhood of our subject in her online Graveyard Rabbit blog from 2012: “Betsy Simpson Clarke was very spoiled and high spirited. They were aristocratic, descending from Worthingtons and Ridgelys, and quite wealthy, owning many slaves. M. William Clarke was very amiable and endeavored to please her but she would frequently fly into a rage and seeking revenge would set free some of the slaves. Finally, Mr. Clarke would leave her and his family, never to return. Betsy, in time, became poor and at 12 years of age, James C. Clarke stopped his schooling at Point of Rocks (MD) to seek employment. He called on the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal but was refused work due to his young age. James pressed on telling he had a mother to support. They admired his courage and started him as a water boy. By age 16, he was a mule driver of a canal boat and held the position for four years eventually rising to the owner of a boat, which sunk in a collision.”

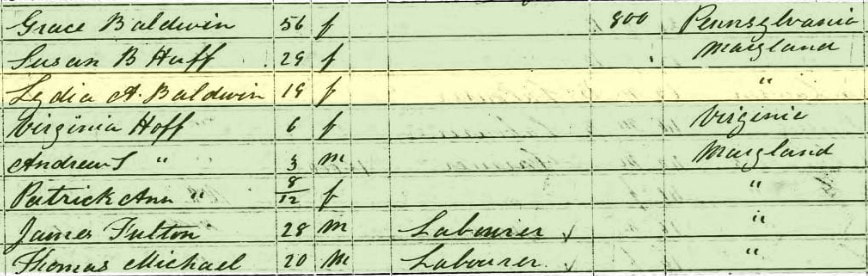

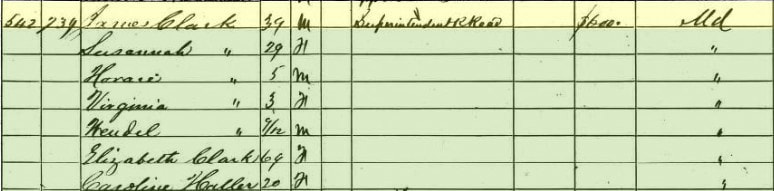

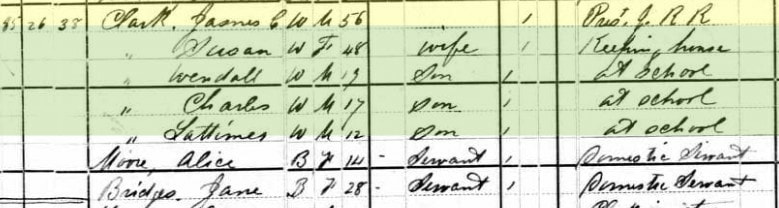

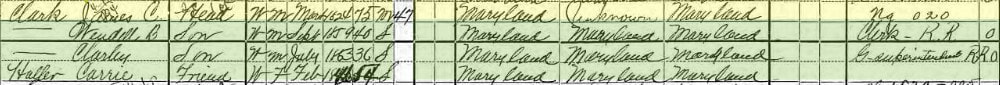

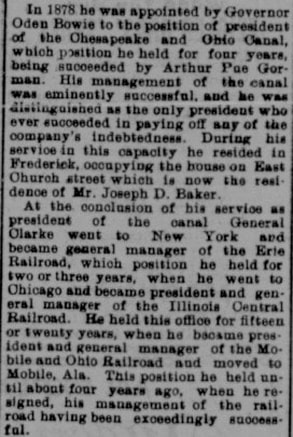

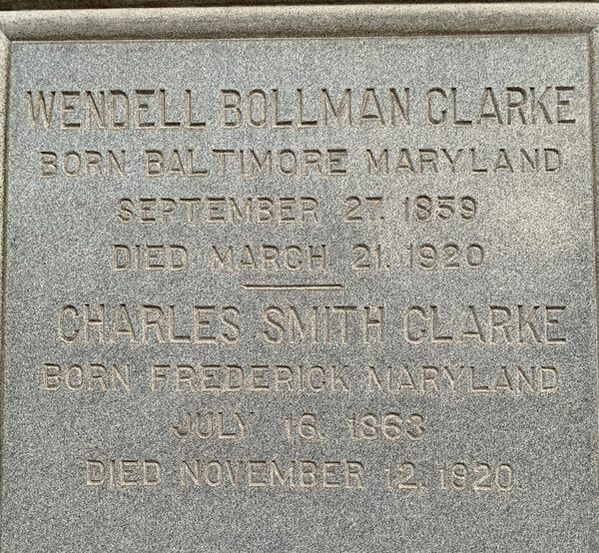

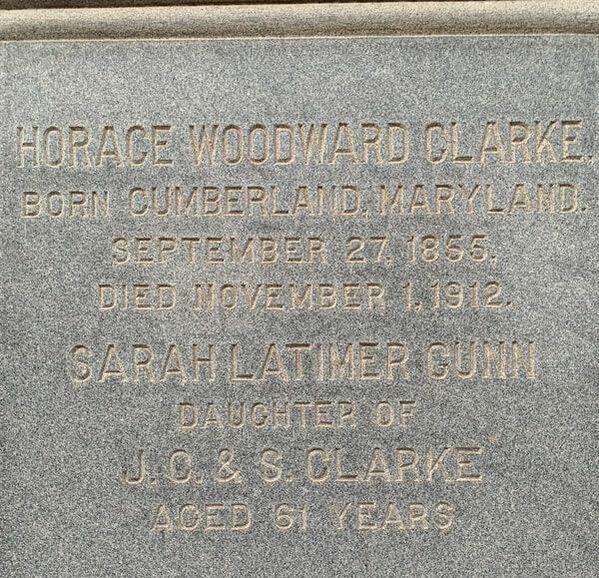

Along the way, James Clarke found time for a family of his own. He married Susannah Shafer (b. 1832) on December 21st, 1852. She was a Frederick native through and through, the daughter of Peter Schaffer and Elizabeth Brunner. Her great-grandfather, Jacob Brunner is connected to building Schifferstadt. A passage found in William Jarboe Grove's 1921 work The History of Carrollton Manor recounts a former love interest of our subject when he was a resident of "Slabtown," a collection simply built slabs (frame and log houses) for the accommodation of B & O Railroad employees. The location was located just north of Buckeystown at a vicinity that would come to take the name of Lime Kiln. Mr. Grove states: "Mr. Clarke at that time was a water boy in the employ of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. A widow living in the best house in town and whose name was Baldwin, had a beautiful daughter by the name of Mary. James C. Clarke fell desperately in love with Miss Baldwin and pressed his suit, but Mary had another lover, James Fulton, also employed by the railroad who was a foreman and like James Clarke was a handsome and fine looking fellow. Miss Baldwin married James Fulton. They raised a large family of children but Mr. Fulton never advanced further than track foreman and finally moved to Iowa. James C. Clarke rose rapidly and became President of one of the leading railroads in the United States. Many other people said Mary made a mistake, but she always seemed happy with her family. " I found the object of James' earlier affection in the 1850 census. Apparently, Mr. Grove had her name mixed up because I found her in the form of Lydia A. Baldwin, daughter of Grace (Buckman) Baldwin and Reginald Baldwin. Lydia married James A. Fulton in May, 1851 and eventually moved to Boone County, Iowa around 1890. She is buried there, dying in 1908, eight years after her husband passed in 1900. As for James and Susannah, five known children would bless the union: Horace Woodward (1855-1912) born in Cumberland, Virginia "Jennie" Osborne (Jeffery) (1857-1933), Wendell Bollman (1859-1920) born in Baltimore, Charles Smith (1863-1920) born in Frederick, Sarah Latimer (Gunn) (1866-1927) born in Baltimore. During the American Civil War, Clarke was kept busy with railroad logistics involving troops. Apparently, in 1862, he left the railroad business to return to Maryland and Frederick County where he became engaged in farming, milling and merchandising. He was part owner in a grocery and wholesale business on the SW corner of Market and Patrick streets (where Colonial Jewelers is located today). The family lived on E. Church Street in the home that would one day become the Evangelical Lutheran Church Parsonage. Clarke was said to have been visited by officers and soldiers of both armies of whom he had friends and acquaintances. I also uncovered a story in which he appeared to be a Southern sympathizer, and even got himself arrested and imprisoned for providing valuable supplies to the Confederates. If that’s not playing both sides of the fence, I don’t know what is? After the war, James C. Clarke took charge of the Ashland Iron Works in Baltimore County, and soon became an owner of interest in this company. He relocated to Baltimore, and in 1866 was elected to the Maryland House of Delegates, and a year later, to the State Senate in Annapolis where he would serve two terms. He was appointed a brigadier-general in the Maryland National Guard by Maryland governor Oden Bowie. In 1870, James C. Clarke was nominated president of his first employer—the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal. He knew the dominance of the “iron horse,” and would jump back to the railroad industry in 1872 after being made president and general manager of the Erie Railroad, where he worked until 1874. He would then head to Chicago, Illinois. For the next fourteen years, Gen. Clarke would work for one of the most prestigious lines in railroad history—the Illinois Central Railroad. He began as superintendent of the railroad’s North Division, but two years in would take up residence in the south region as he lived on Bourbon Street in New Orleans from 1876-1883. He was elected president of the Illinois Central in 1883, and held this post for nearly five years. These duties brought him back to residency in Chicago. From 1888-1902, Clarke returned south and spent a decade with the Mobile (Alabama) & Ohio Railroad, becoming the firm’s president early on. He took a flailing operation, and made it successful again by the end of his tenure. While living abroad, Mrs. Susanna Clarke died in September, 1892. General Clarke finished an incredible 58-year career in the burgeoning transportation industry of our nation. Over his lifetime, he saw the birth of both the C&O Canal and B&O Railroad. He not only worked for both entities, but helped both grow under his managerial leadership. Mending Fences Gen. Clarke returned to Frederick regularly to visit old friends, plus he owned three farms in the area. The small town always felt like true home, even though his profession took him to reside elsewhere. Clarke always retained an interest in town growth and affairs. Ironically, he is attached to another controversial story involving fencing in downtown Frederick. Beginning in 1818, Court House Square resident, Col. John McPherson began installing iron railings around the Frederick county Courthouse and subsequent public lawn. This was forged at McPherson’s Catoctin Furnace operation located in the north sector of the county between Lewistown and Mechanictown, destined to become Thurmont. Apparently the neighbors of “the Square,” consisting of the town’s “upper crust,” were annoyed with the recent phenomena of rogue animals grazing on the prestigious courthouse lawn that once boasted legal luminaries such as Francis Scott Key, Roger Brooke Taney and Reverdy Johnson. What seemed like a philanthropic venture by McPherson soon angered the general citizenry as they saw this symbolized an obtrusive wall to a public place and access to courthouse amenities and officials. It also seemed as an extension of the adjacent neighbors hoping to keep all others out of their prestigious neighborhood unless they had official court business to attend perform. The squabble would last for decades, as a matter of fact, eighty years. The railings were finally removed in 1888. To help pacify the masses, Gen. Clarke found it necessary to offer an olive branch to all citizens by providing a perfect centerpiece to the courthouse green—an ornamental fountain. The Clarke fountain was duly dedicated to all people of Frederick. Again, I want to point out the irony here as both “railing stories” involve Clarke, especially fitting because he built his career, fortune and reputation on iron rails! Gen. James C. Clarke could be found residing in Mobile, Alabama with his two sons in 1900. Both sons, Wendall and Charley, worked for the railroad. Wendell is listed as a clerk, and Charley as superintendent, taking over his Dad’s position with the Mobile & Ohio Railroad.

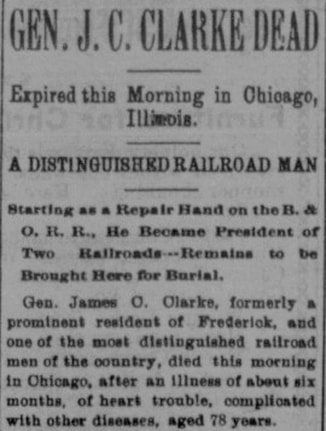

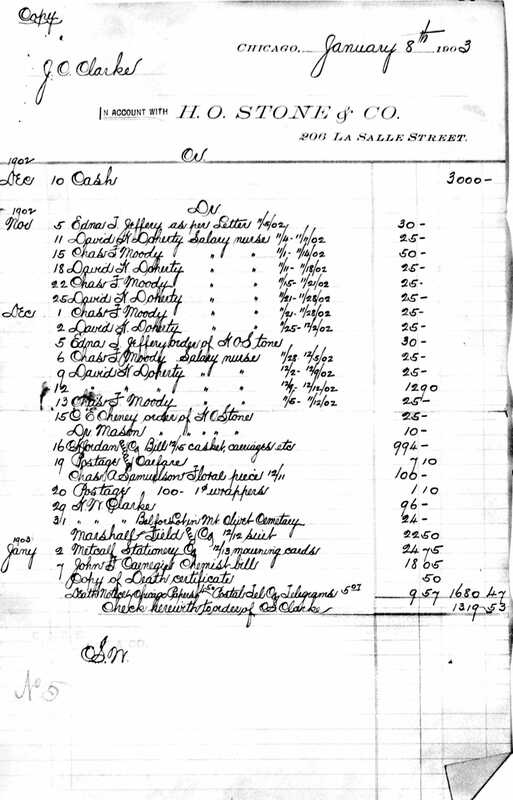

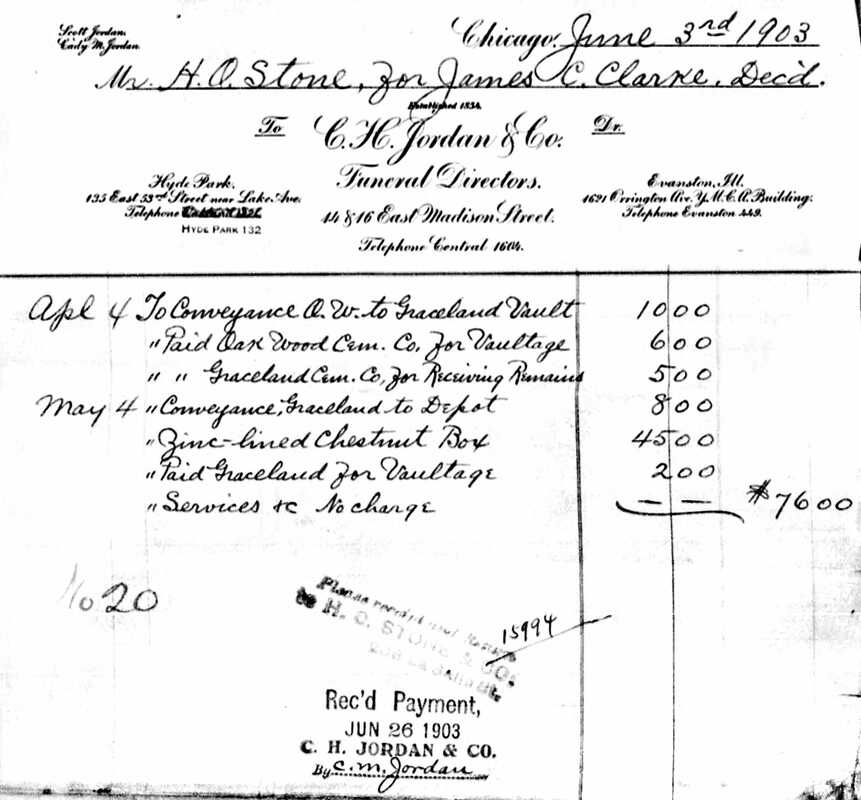

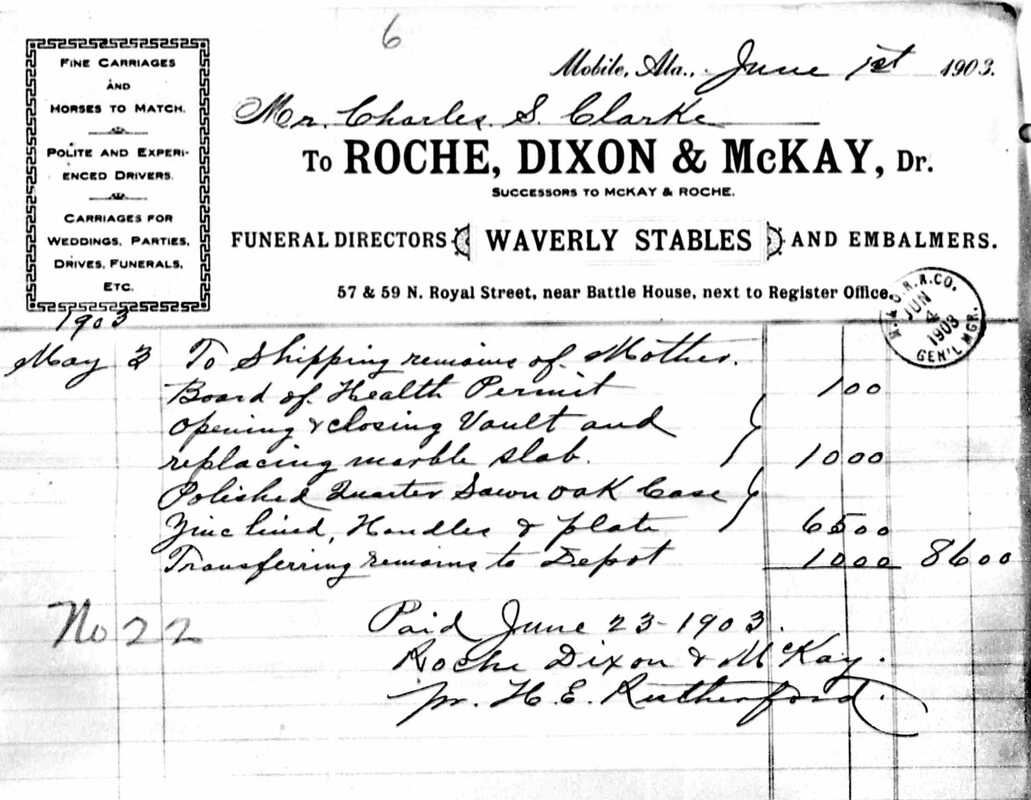

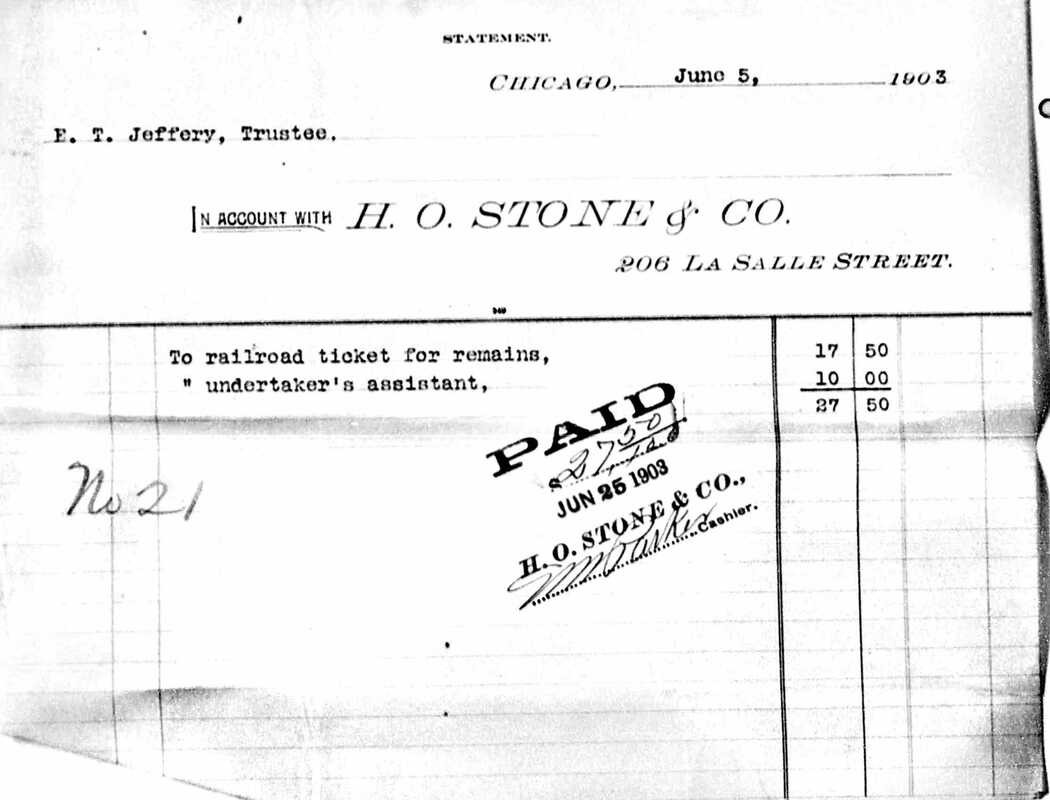

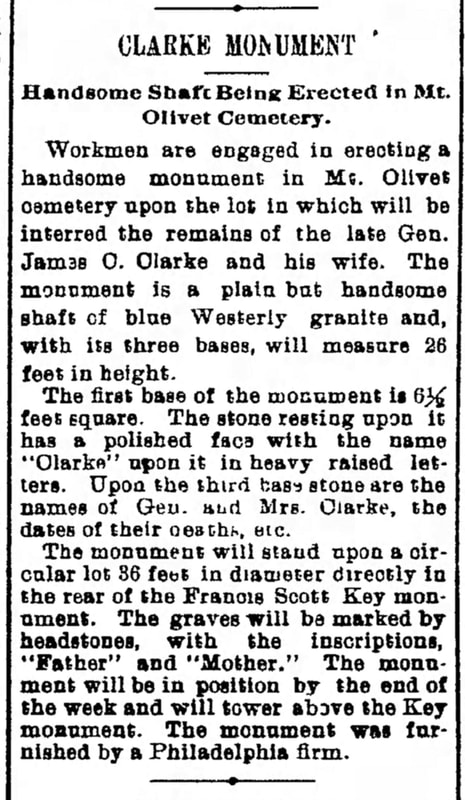

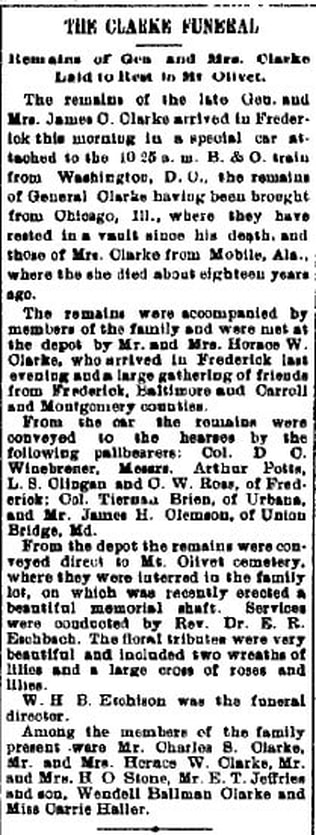

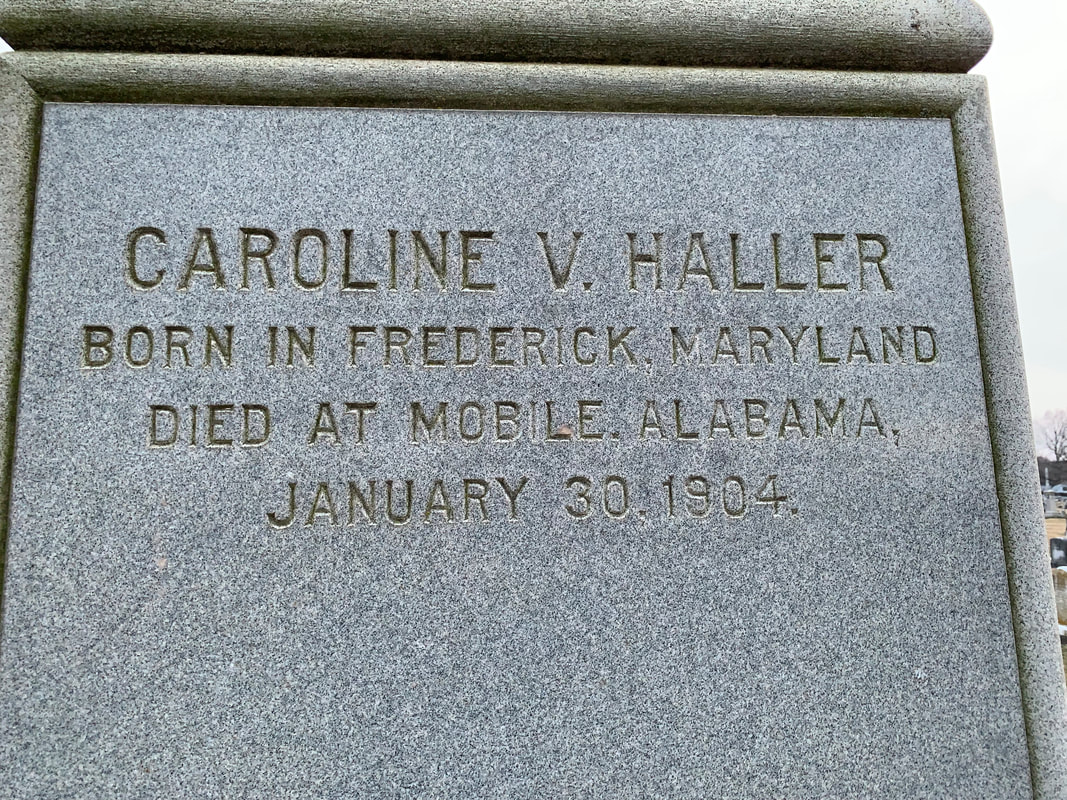

Clarke's body was handled by Chicago's C. H. Jordan & Co. Funeral Directors, and appears to have been taken to Oak Wood Cemetery in Chicago for a funeral service of some kind. Here, Gen. Clarke was placed in a storage vault, as the season would not guarantee favorable weather to bury him in Frederick in the heart of the winter season. This was quite a common occurrence in a time devoid of better equipment to excavate frozen ground. Plans were also made to bring Mrs. Clarke's body to Frederick from Mobile, where she had been buried in Graceland Cemetery. I assume that the weather also played a factor here as well. Construction soon commenced on an elaborate memorial obelisk to adorn the Clarke burial plot in Frederick. Both Gen. and Mrs. Clarke's bodies would be transported by train back to Frederick on the morning of May, 6th, 1903. A procession brought the bodies to Mount Olivet where graveside services were held under the shadow of the magnificent memorial that had been recently finished. I'm not sure whether or not the procession passed through Clarke Place, but I can guarantee that it went by Clarke place en-route to the cemetery.  Graves of Harry and Anna Bowers in Area D/Lot 3 with Grove Stadium in background Graves of Harry and Anna Bowers in Area D/Lot 3 with Grove Stadium in background In time, sons Horace (d. 1912), Wendell (d. 1920), Charles (d. 1920) and daughter Sarah L. Gunn (d. 1927) would join their parents here in Mount Olivet. One additional burial in this lot was that of Caroline Virginia Haller (d. 1904). Ms. Haller can be found living with the family in Mobile in 1900, and is listed simply as a friend. She could have served as a housekeeper or nanny for the children as she lived with the family for decades. Carrie, as she was known, attended the May, 1903 funeral for Gen. Clarke, but would be buried in this same lot the following February after her death back in Mobile in January, 1904 at the age of 64. A final irony here lies in the fact that the vicinity of southern Frederick City was commonly referred to as “Hallerstown,” long before there was ever a Clarke Place. This was said to be due to the influx of family members with that surname. So next time you visit any of the Clarke “places” in town be it the street, Court Square fountain or burial-memorial site here in Mount Olivet, be sure to give homage to a true pioneer of transportation innovation. And I would also suggest that you keep all baseballs "out of site" from crotchety Mrs. Baker as well—she's buried about 20 yards to the left of the Clarke monument on the corner of Area D. So fitting that Harry Grove Stadium at Nymeo Park is such a short distance away.

5 Comments

shane shanholtz

3/8/2019 06:59:53 pm

great story as always thanks

Reply

Lee Palmer Redmond

3/8/2019 09:15:28 pm

Hey Chris, wonderful article. Since my grandmother used to live on Clarke Place, I’ve done quite a bit of research as well on the street and it’s first residents. My father actually has the NOTICE sign that was at the entrance to Clarke Place.

Reply

Mary Berg

3/9/2019 05:58:53 am

My husband and I lived in the beautiful Bowers house on Clarke Place for over 30 years. We participated in five Christmas house tours. Thank you for this wonderful article.

Reply

Smith Mark A.

3/9/2019 04:25:00 pm

Great article - we are lucky enough to be living in the Bower house now. The metal posts still exist by our garage on Scott Key - where it was chained off in the “gated community” days.

Reply

Pat Richey

3/12/2019 12:35:41 pm

Grateful for this fascinating article! I was one of many students at Maryland School for the Deaf which faces the Bower house on Clarke Avenue (my years there were fall of 1944 through spring of 1956. Back then, beside the Bower house on South Street was a gas station selling soda pops, candies, ice cream, etc. My oldest sister of five children attending MSD told me, many years later, that she used to sneak out at night to go to that station to buy ice cream. I can't recall what she said regarding how she did it...impossible due to nightly lock-up!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed