|

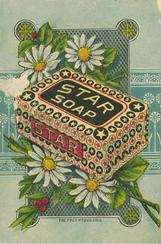

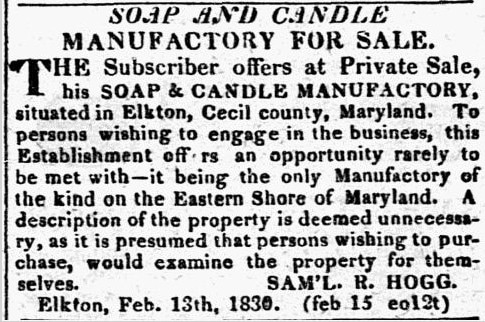

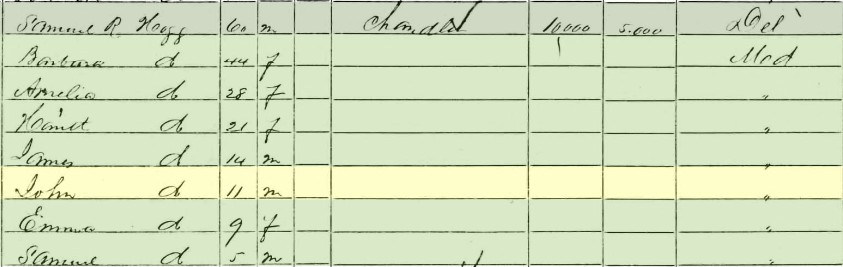

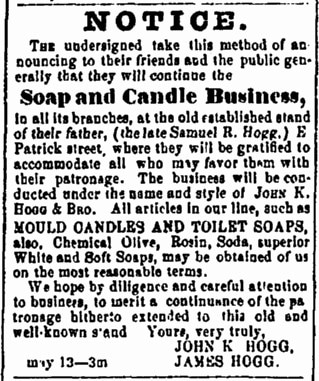

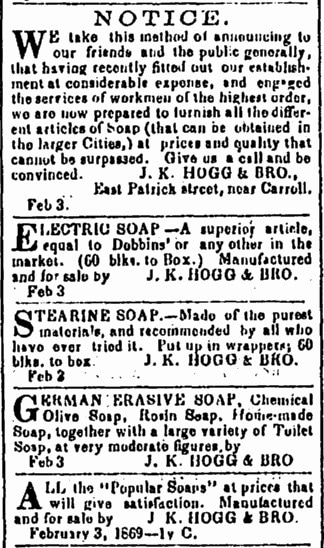

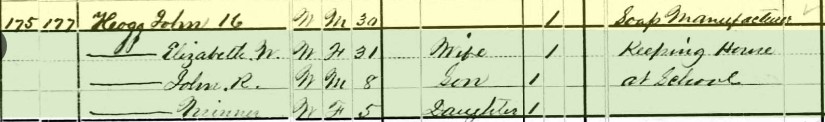

“As happy as a pig in mud” is an age-old idiom still used today. Along similar lines, another popular, pork-related phrase is “He is in hog heaven!” or “She went hog wild!” In all these cases, the subject seems to be enthralled, and satisfied, while engaged in some pleasurable act, all the while captivated within a desirable environment. Oftentimes, gluttony of some sort is implied. The basic underlying premise of the first phrase is that pigs are happy in mud. Not knowing the exact religious stance of most porcine-based creatures, I’m assuming that a mud-filled pen or trough is the closest thing to “heaven” that a pig, boar or hog will experience. Options are limited since it is generally known that they seldom make it off the ground, beings they aren’t known to fly. Interestingly, our human view of mud is totally congruent to that of swine. Unless involved in a social endurance event activity or spa treatment, we generally are very “unhappy” in mud. Even just the hint of mud on our shoes or clothes is repulsive, and we make extra efforts to avoid wet, soft earth as much as possible.  So what exactly is it about mud that makes pigs so gleeful? Researchers say that wallowing in the mud offers several practical benefits, like keeping swine cool. Reasons range from sun protection to parasite removal to temperature regulation. In April 2011, Researcher Marc Bracke of the Netherland’s Wageningen University and Research Center shared great insight after conducting a study for the Journal of Applied Animal Behavior Science. Bracke wrote: “Pigs have few sweat glands, high body fat and a barrel-shaped torso that stores heat. Wallowing can lower a pig's temperature by 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit, making it more efficient than sweating would be even if pigs had lots of sweat glands. A mud bath is more cooling than a dip in cold water because the water in mud evaporates off the pig's coated body more slowly, allowing the animal to reap the cooling benefits of evaporation for longer. But even in cool weather, pigs still wallow, suggesting that the magic of mud doesn't just lie in thermal regulation, Some wild pigs seem to use mud baths to scrape off parasites such as ticks and lice; they may also rub their scent glands around wallowing areas, possibly as a way of territory marking.” So there you have it, the secret behind “porcine mud bliss!” Now what does this have to do with Mount Olivet? Well I was recently triggered by a few tidbits picked up while researching the cemetery. First off, William T. Duvall (1813-1886), Mount Olivet’s first superintendent, actually raised hogs in a pen on the premises. I also stumbled across a few old prominent Frederick families having names that could be stretched to relate to swine terms, but certainly that is where the connections end. Mount Olivet has three graves associated with the Pigman family who were originally buried in the All Saints’ Church burying ground (once located downtown off E. All Saints Street). Meanwhile, the cemetery boasts 10 members of a family having the last name of Hogg. Both surnames were fairly new to me, however I recalled the latter from childhood with the fictional character of Jefferson Davis “J.D.” Hogg. Known more commonly as “Boss Hogg,” this was the unscrupulous county commissioner from the legendary Dukes of Hazzard television show. Tom Kohlhepp, an industry colleague and history lover, recently alerted me to one of the Hogg family being another unsung, and forgotten, individual buried within Mount Olivet’s gates. This was John K. Hogg, whose noteworthy achievement came in 1870, when he successfully registered U. S. Trademark No. 9 with the United States Trademark and Patent Office. That’s right, this was the 9th trademark in US history—and ironically Hogg’s entry was for soap. For quick review, a trademark is defined as a recognizable sign, design or expression which identifies products or services of a particular source from those of others. The trademark owner can be an individual, business organization, or any legal entity. A trademark may be located on a package, a label, a voucher, or on the product itself. We are surrounded by registered trademarks ranging from names/logos pertaining to soft drinks, candy bars, professional sports teams, car manufacturers, sneakers, and household cleaning agents. John Kunkel Hogg was born in Frederick on October 11, 1848. He was the son of Samuel Robinson Hogg, Sr., a native of Delaware who had come to town after living in Elkton (MD) in the 1830’s and opened his own business as a tallow chandler, a dealer in household items such as candles, wax, oil, soap, and paint. John’s mother was Mr. Hogg’s second wife, Barbara Ann Kunkel. Many of the Kunkels are also here in Mount Olivet, and of particular note are John’s grandfather John Kunkel II and uncles John B. Kunkel and Jacob Kunkel, a US congressman. These three gentlemen were onetime owners of the Catoctin Furnace (mid-19th century), and specialized in the production of what else—“pig iron.” John K. Hogg and brothers James and Samuel R. Hogg, Jr. learned and worked the family business with their father, who opened a small manufactory adjacent their home on the north side of East Patrick Street, near the intersection with Carroll Street. The home and lot once extended through to Church Street and boasted a two-story stone dwelling and a plentiful fruit orchard. Samuel Hogg purchased the property at auction in 1837. I have not claimed the exact address but strongly deduct that the Hogg home and store was located in the vicinity of the parking lot for downtown Frederick’s US Post Office, and along Chapel Alley.  A view looking north up Carroll Street and showing the old Frederick News-Post/Trolley Freight Terminal building (right) and the intersection with E. Patrick Street. The author believes the potential Samuel R. Hogg household to be at the NE corner of this intersection with the actual house immediately to the right of the trolley car pictured Samuel R. Hogg, Sr. was quite active in Frederick’s business and civic community. He was the father of 10 children, and said to have been an outspoken Unionist during the American Civil War. Hogg’s Soap was the chief product his small industry, and would be carried by merchants in other cities, including Baltimore. Mr. Hogg died in April 1868 at the age of 68, and was buried in Mount Olivet at a well-attended funeral by his many friends and neighbors. Ads began appearing one month later in the local Frederick Examiner newspaper announcing the fact that sons John K. and James Hogg would be carrying on the business their father had meticulously crafted over the balance of his life. One year later, the firm of J.K. Hogg and Bro. announced improvements to their store and works, and boasted a wide variety of soaps that could only be gotten by customers in larger cities. One year later, John would register for his trademark. In the meantime, John and James amicably dissolved their partnership, and John made a solo effort of it, apparently with help from kid brother Samuel R. Jr. In early 1870, an auction was held to sell off the old homestead and manufactory. The family appears together in the 1870 census, but soon they would depart Frederick, heading east to Baltimore and eventually bringing the family soap business with them.

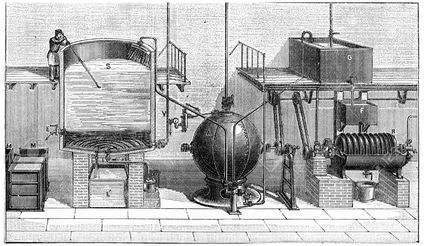

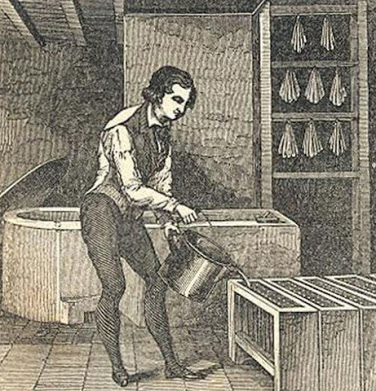

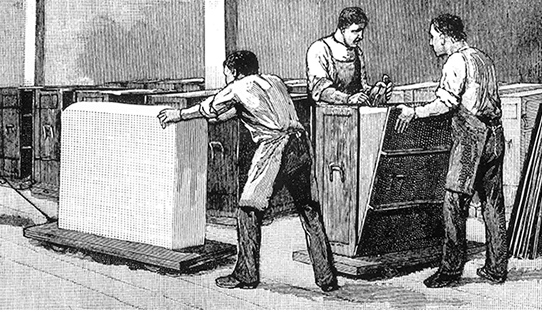

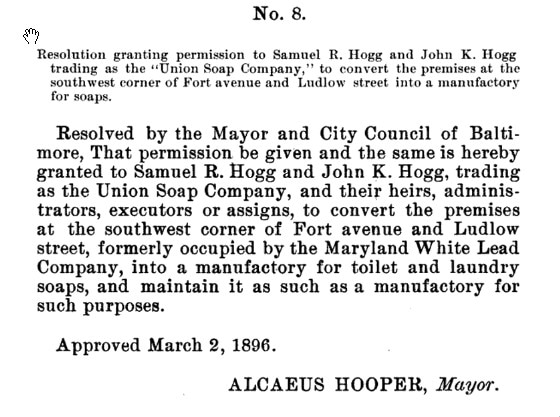

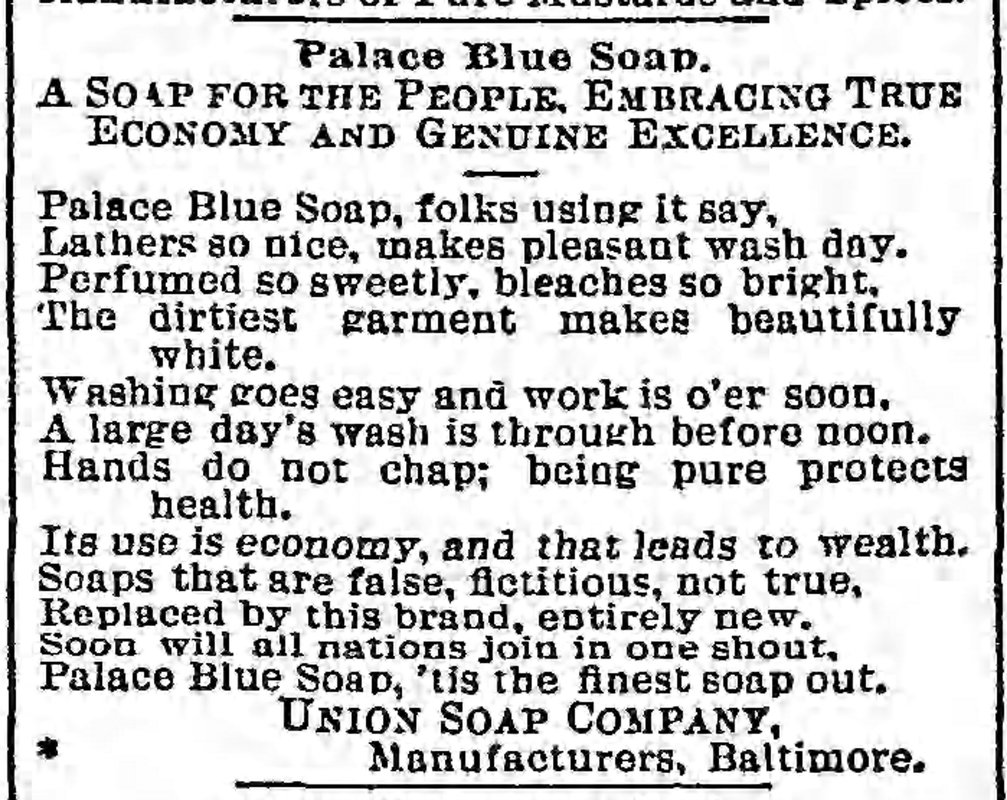

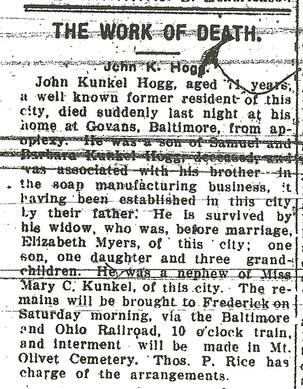

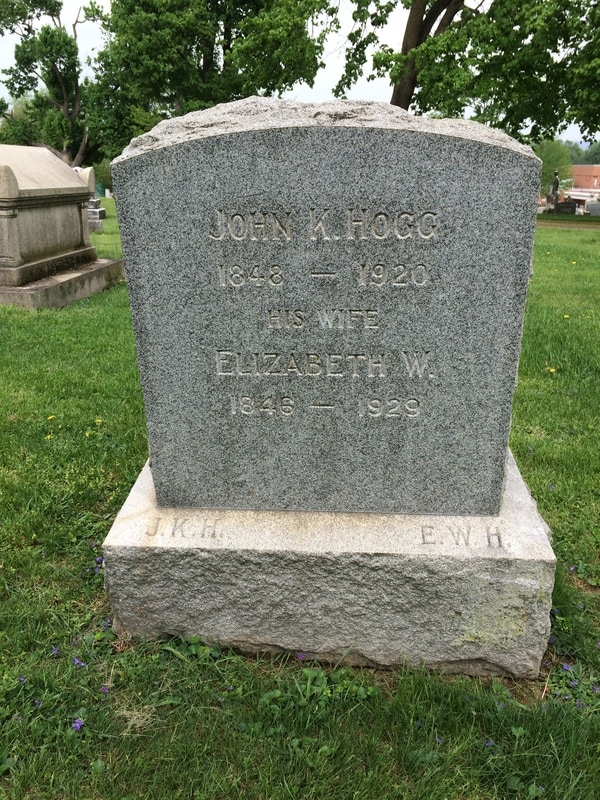

I wasn’t able to glean much of John K. Hogg’s personal life other than his marriage in 1870 to Elizabeth Wilson Myers (1846-1929), the daughter of German immigrants. The couple can be found living with John’s mother, Barbara, in Frederick in 1870 as newlyweds. A son, John Robert, would be born to them in October, 1871. By 1873, they had moved to Baltimore and were residing and working at 38 N. Paca Street, a few blocks south of the famed Lexington Market. John K. and teamed up with his brothers again to operate a grocery store under the name of J. Hogg and Bro. They also were manufacturing Diamond Yeast Powder. Today, this location is encompassed by the campus of the University of Maryland, Baltimore.  A daughter Minna would join the family in 1875. They appear to have moved around quite a bit, living in the downtown/west Baltimore area of the city at locations such as Mosher, Stricker and Arlington streets. Back to business, John and Samuel would start a soap-making firm under the name of the S. R. H and Co. in the Calverton section of town. Perhaps they did this to honor their father. The Brothers Hogg eventually changed this moniker to the Union Soap Company and advertisements appear in newspapers throughout the 1880’s and 1890’s. I don’t know what became of their production of Star Soap, as I have found another firm, under the ownership of the Schultz family, producing Star Soap out of Zanesville, Ohio in the 1880’s. The Schultz brothers would continue until 1903, when the Proctor & Gamble Company would purchase the endeavor and move it to Cincinnati, a city once known as “Porkopolis” because it was the one-time center of hog packing for the country. Proctor and Gamble were the makers of Ivorine Soap, which they smartly renamed Ivory Soap. In 1896, the Hogg brothers petitioned the Baltimore City Mayor and City Council for permission to convert the former Locust Point neighborhood property of the Maryland White Lead Company (located near Fort McHenry on the southwest corner of Fort Ave and Ludwell Street) into a manufactory for toilet and laundry soaps.  1875 illustration depicting soap-making in isolation, extraction with glycerin. 1875 illustration depicting soap-making in isolation, extraction with glycerin. I was curious as to what the soap production process consisted of—first having to explore the makeup of soap itself. Here’s what I missed while daydreaming in high school chemistry class (courtesy of Wikipedia): In chemistry, a soap is a salt of a fatty acid. Household uses for soaps include washing, bathing, and other types of housekeeping, where soaps act as surfactants, emulsifying oils to enable them to be carried away by water. In industry they are also used in textile spinning and are important components of some lubricants. Metal soaps are also included in modern artists' oil paints formulations as a rheology modifier. Soaps for cleaning are obtained by treating vegetable or animal oils and fats with a strong base, such as sodium hydroxide or potassium hydroxide in an aqueous solution. Fats and oils are composed of triglycerides; three molecules of fatty acids attach to a single molecule of glycerol. The alkaline solution, which is often called lye (although the term "lye soap" refers almost exclusively to soaps made with sodium hydroxide), induces saponification. In this reaction, the triglyceride fats first hydrolyze into free fatty acids, and then the latter combine with the alkali to form crude soap: an amalgam of various soap salts, excess fat or alkali, water, and liberated glycerol (glycerin). The glycerin, a useful byproduct, can remain in the soap product as a softening agent, or be isolated for other uses.

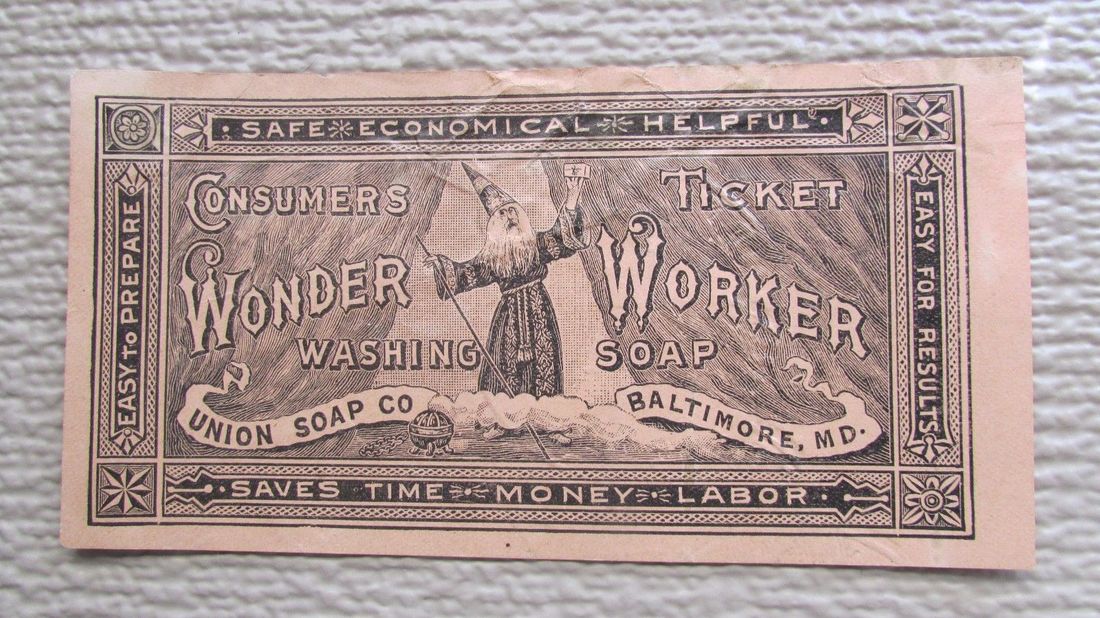

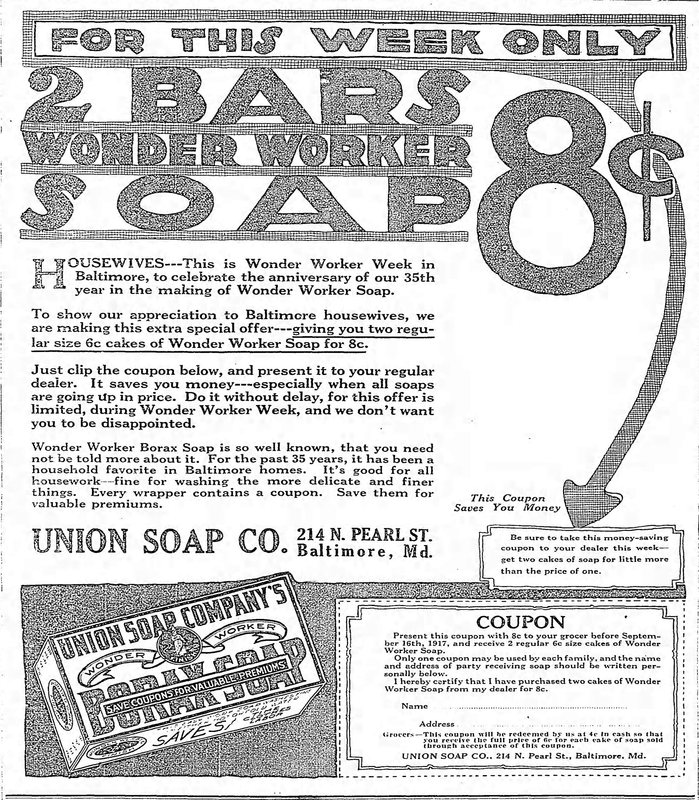

Into the 1900’s, the soap works would move back into downtown with locations on Arch Street and later Pearl Street. Newspaper and advertising cards can be found “barking” another signature product entitled “Wonder Worker Washing Soap.” The last citing I found of one of the company’s ads was in 1917.

3 Comments

Lisa McEwan

4/23/2017 10:31:35 am

love this article.

Reply

Jocelyn Wetzel

4/25/2017 07:27:47 pm

This is a brand new story for me and very interesting. Keep up the good work.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed