|

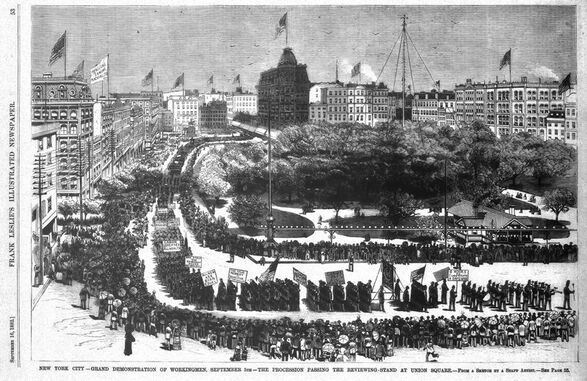

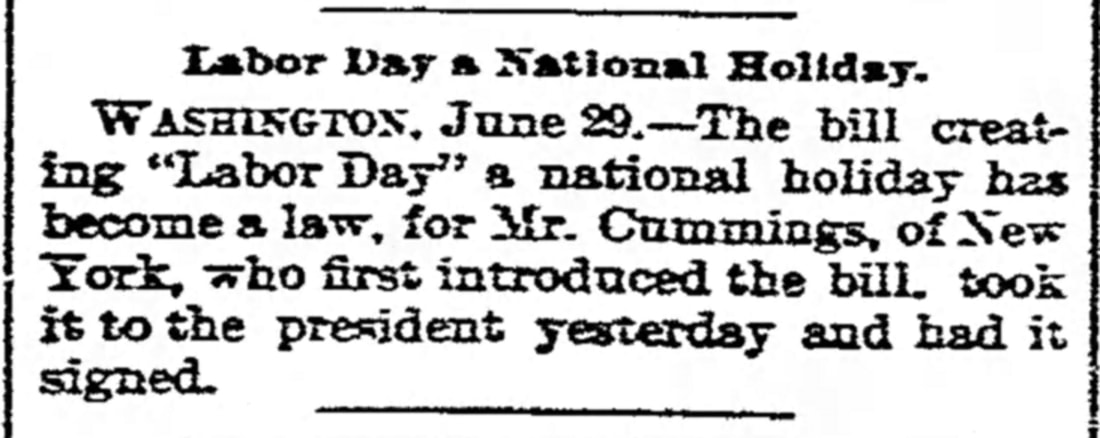

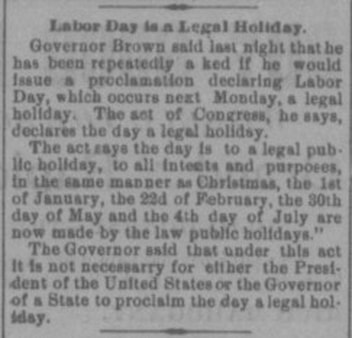

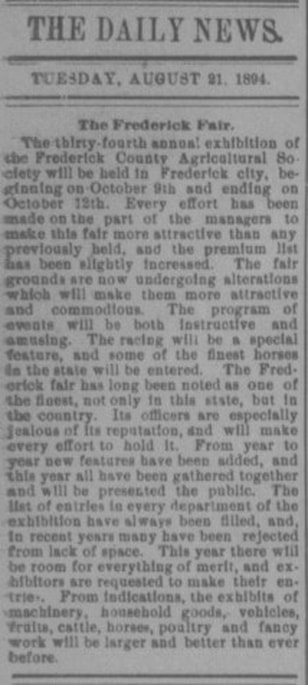

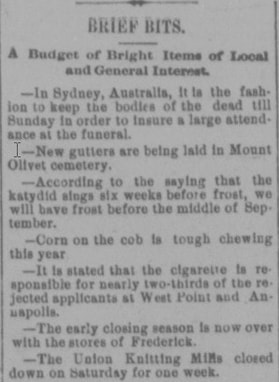

Labor Day, the public holiday celebrated annually on the first Monday in September, honors the American labor movement and the power of collective action by laborers—the lifeblood of the workings of our society. According to the Department of Labor's official description, “Labor Day is dedicated to the social and economic achievements of American workers, and constitutes a yearly national tribute to the contributions workers have made to the strength, prosperity, and well-being of our country." Of course, many folks these days have lost sight of the true meaning behind this day, simply because it sometimes gets lost as the depressing “pack-up” day of a long weekend (Labor Day Weekend). Worse yet, Labor Day sadly signals the "unofficial end of summer" as most annual family vacations have already been taken, and children are heading back to school. In addition, traditional fall activities and sports are set to soon commence, leaving behind the outdoor recreational opportunities such as picnics and amusement park visits afforded by warm, sunny weather. Here in our area, the temperature begins to cool at this time, and one of the major associations with summer is severely affected by the change of season—that of visiting the beach. It’s no wonder that the leading destination for Labor Day weekend involves ocean resorts. Naturally, this is due to the fact that a return of warmer weather (especially dictating higher temperatures suitable for ocean water swimming and sunbathing) will not come for another eight months. Let’s get back to the origin of the Labor Day holiday. Beginning in the late 19th century, the trade union and labor movements grew. Trade unionists proposed that a day be set aside to celebrate labor. In 1882, "Labor Day" was promoted by the Central Labor Union and the Knights of Labor, which organized and executed a parade in New York City. In 1887, Oregon became the first state of the United States to make Labor Day an official public holiday. I found a first mention of “Labor Day” in our local paper that same year, and in 1888, the September 4th edition of the Frederick Daily News carried several articles on its front page chronicling celebrations and parades held in major cities throughout the nation. It would eventually become an official federal holiday in 1894, and at this time, 30 states including Maryland officially celebrated Labor Day. Interestingly, the Frederick Daily News included the following brief, and seemingly sarcastic, remarks about the new holiday in an edition published by the firm and its staff of employees on Monday, September 3rd— Labor Day itself.

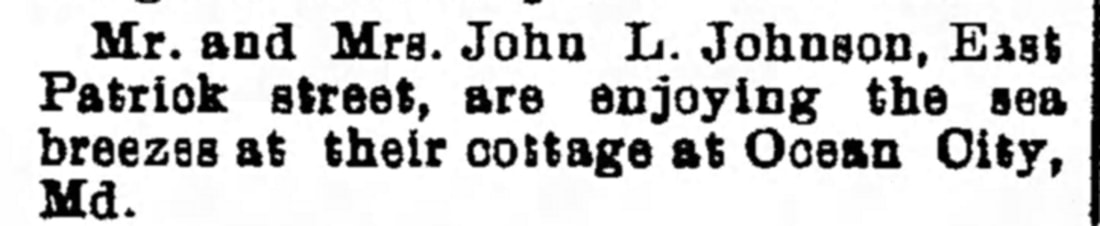

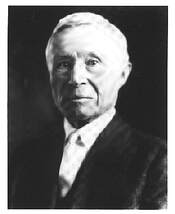

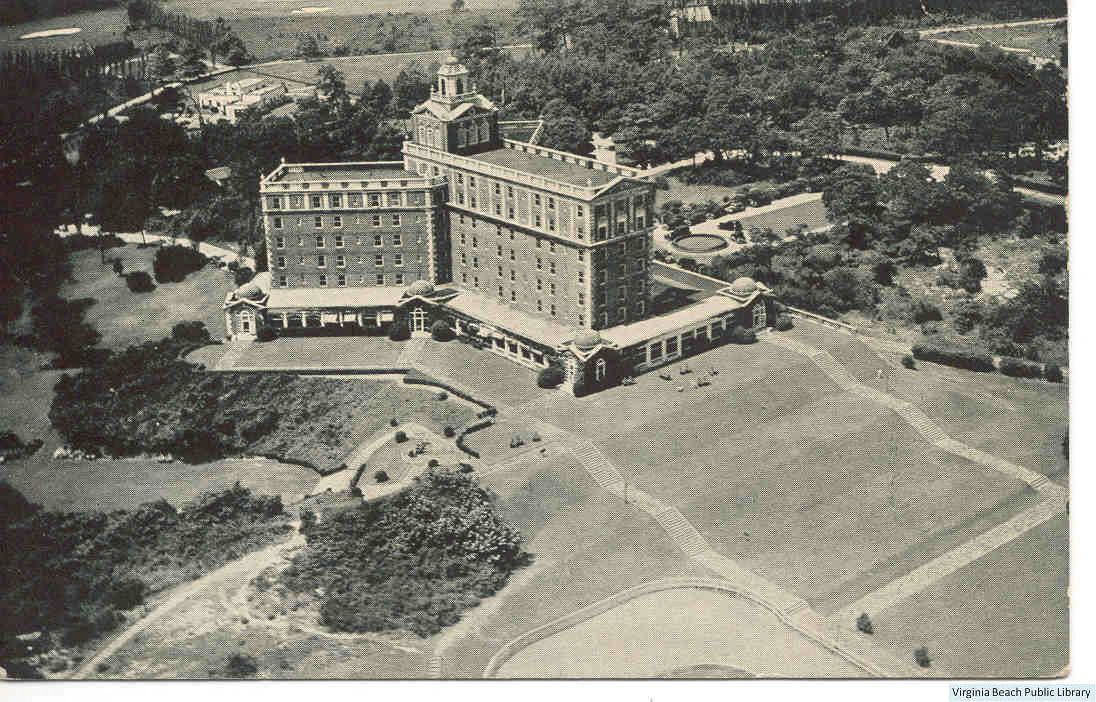

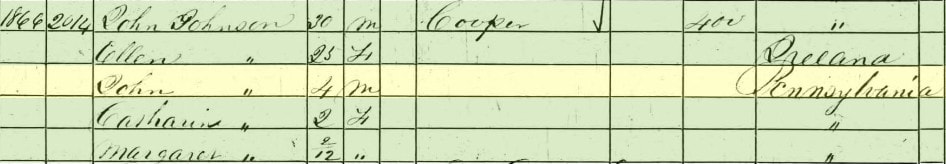

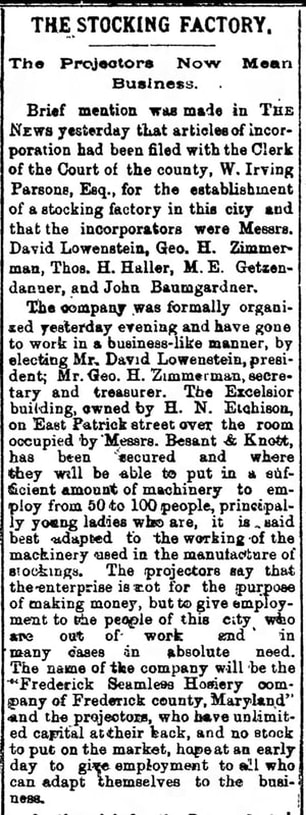

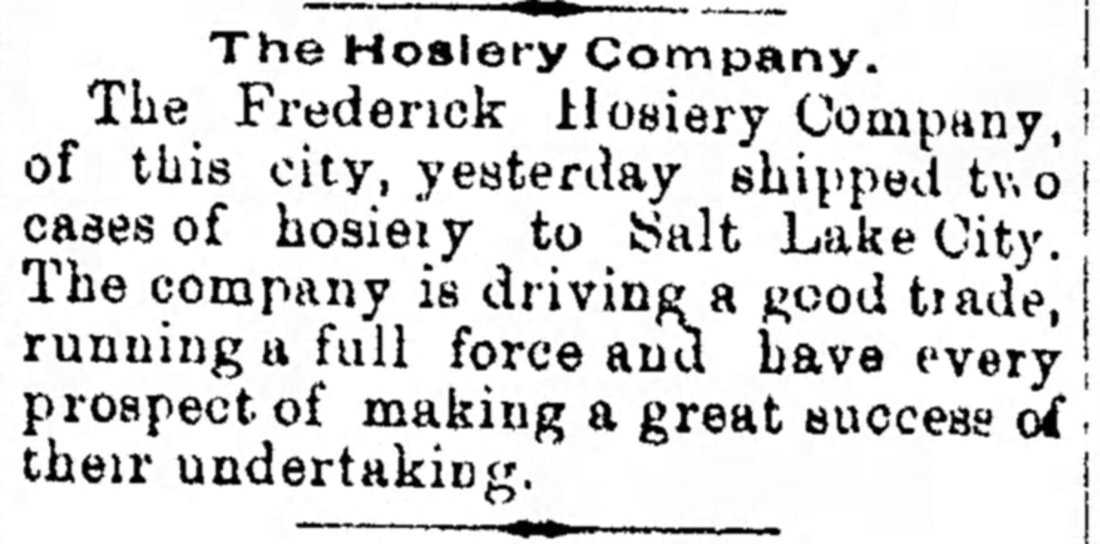

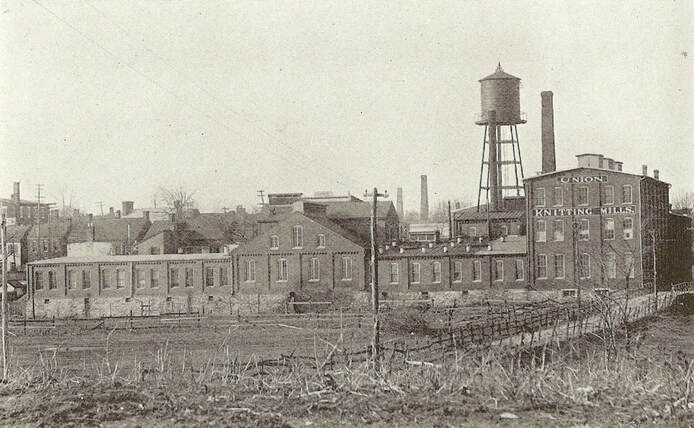

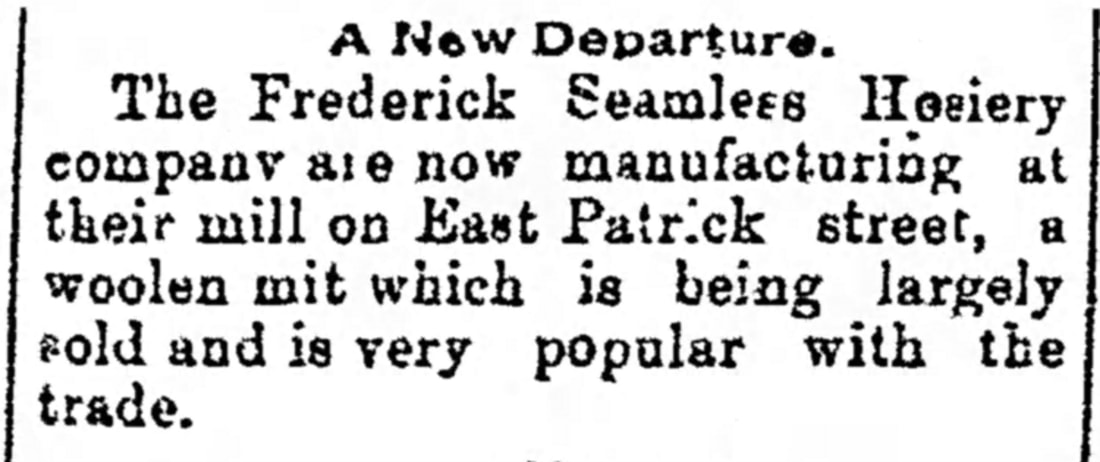

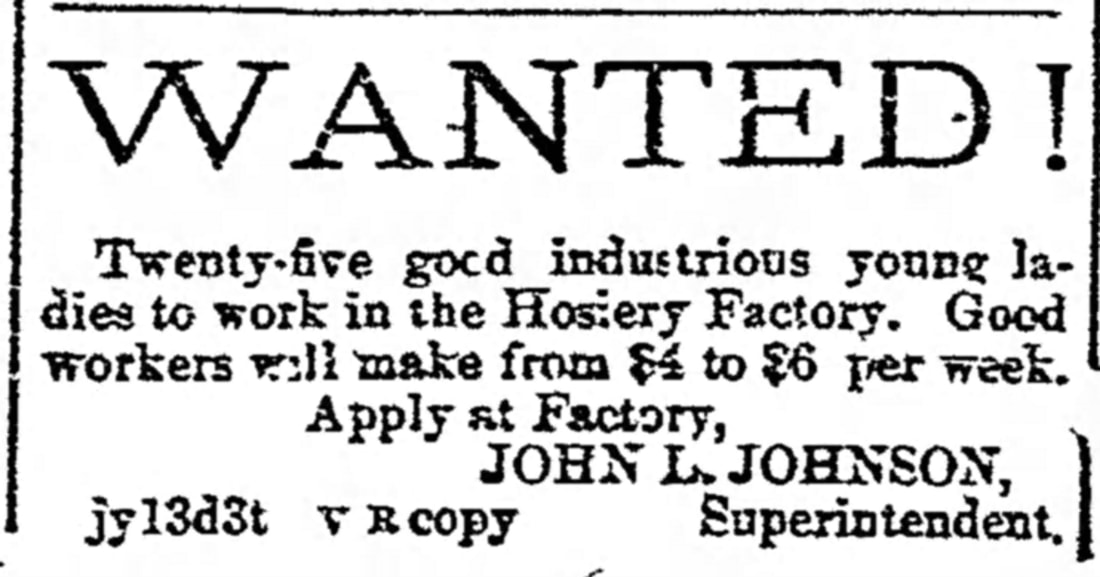

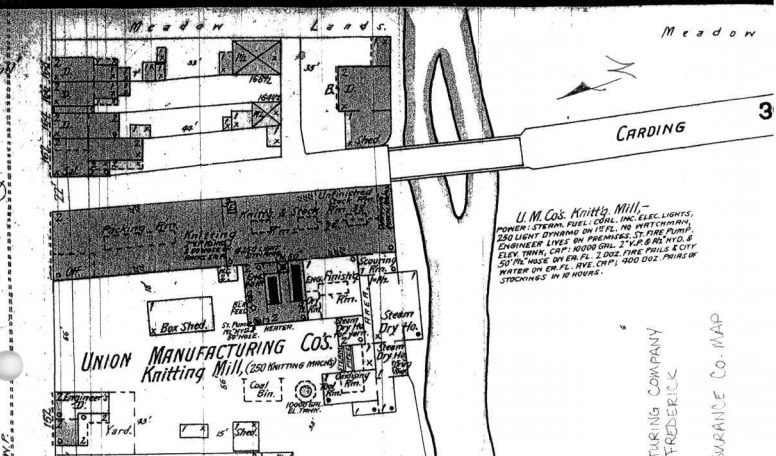

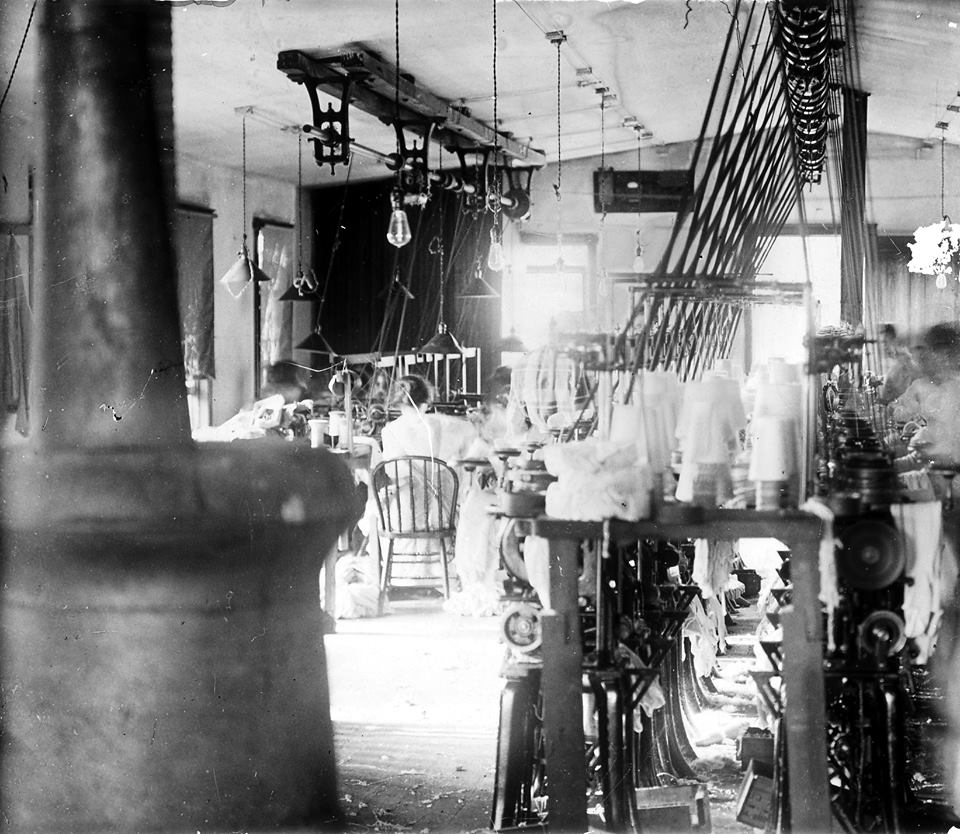

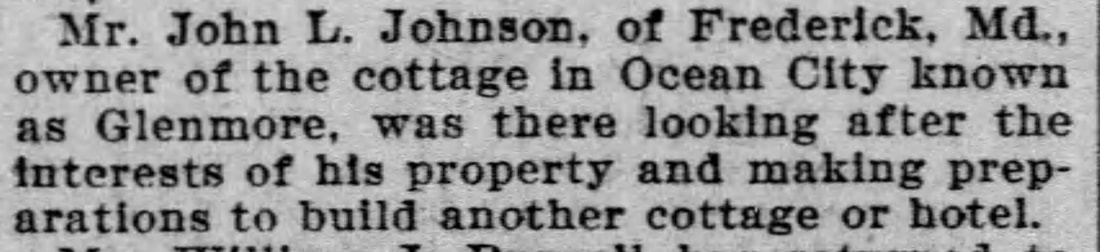

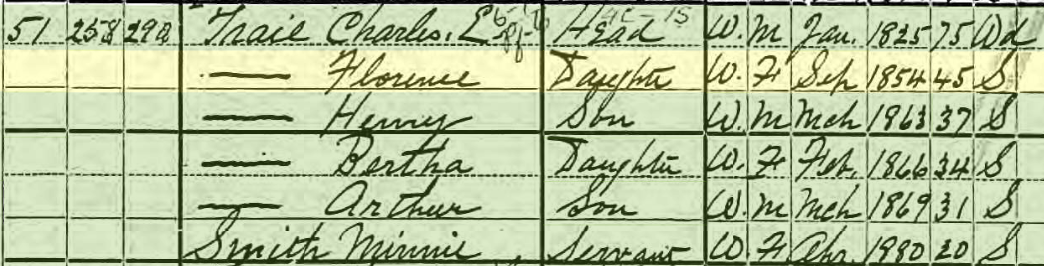

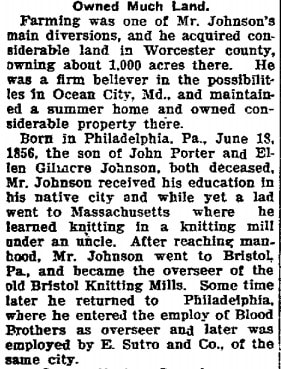

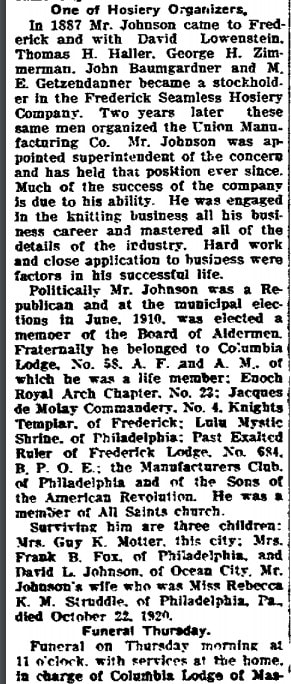

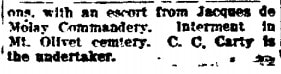

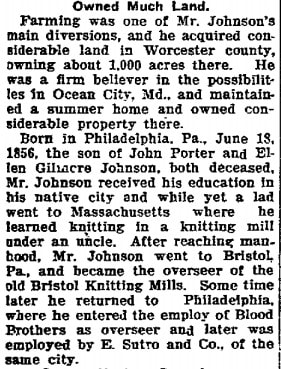

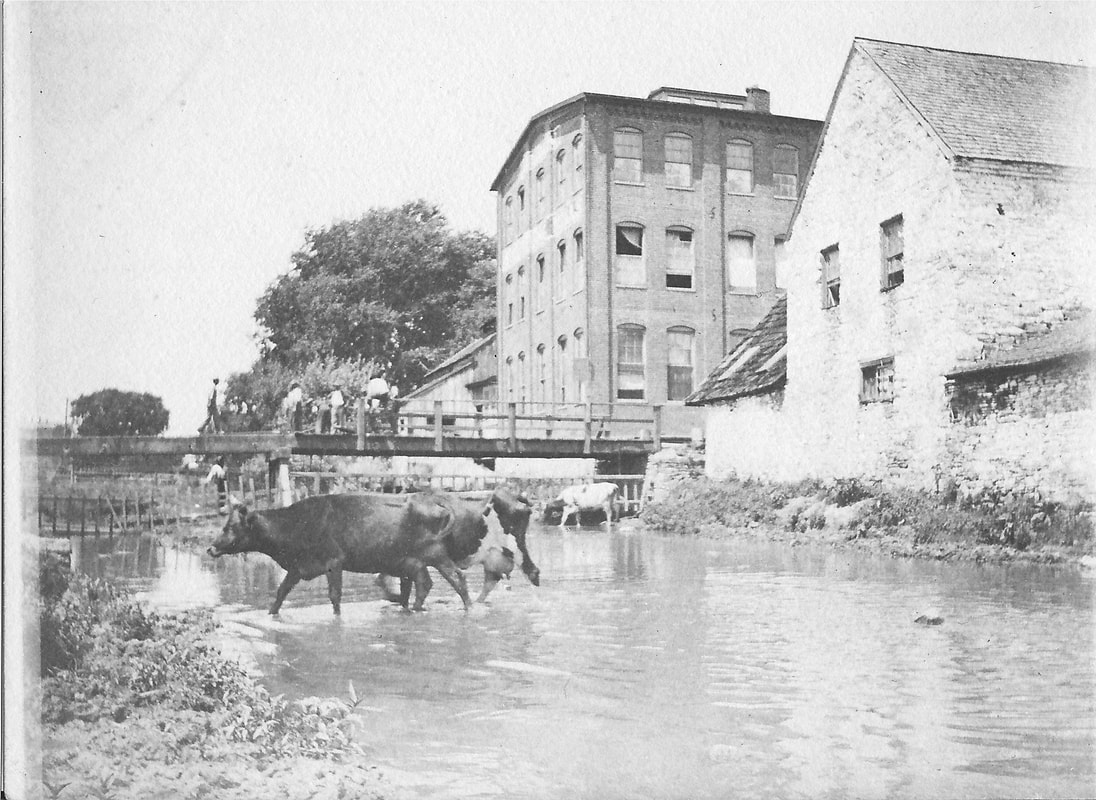

Now, for decades there had existed small-scale industries here in Frederick such as grain mills, canneries, tanneries, lumberyards and iron works, however the spirit of unionized labor was non-existent as opposed to its presence in the aforementioned cities in our region. One reason, I was told years ago, hinges on the fact that the founding families of town wanted to keep big industry out of Frederick, as exemplified by only allowing a train spur-line here coming up from Monocacy Junction. Now think about how the railroad influenced Baltimore, Hagerstown, Martinsburg and Cumberland, giving rise to more factories and industrial pursuits because of the transportation component? It did the same for Brunswick and Thurmont on a smaller scale, of course. In time, however, a shift away from the train to vehicular shipping (on a system of interstate highways) had serious negative consequences on the former places the railroad had transformed. Frederick, however remained virtually unscathed. I was excited to find several mentions of a local captain of industry who seemed to have made a ritual out of going to the beach around Labor Day weekend. His name was John L. Johnson and he was the managing superintendent of the Union Knitting Mill, formerly known as the Frederick Seamless Hosiery Company. Mr. Johnson would travel to the Maryland seashore regularly throughout summer, having built a beach cottage in old Ocean City, and came to own multiple farms on the Isle of Wight Bay in West Ocean City near Drum Point (north of the route 50 bridge). In fact, in that edition of the Frederick Daily News from September 3rd, 1894, I found John L. Johnson’s staff of employees had actually been given the week off. The irony of it all is that this industrial complex was one of the first, and only, large operations in Frederick’s history, and had come to have the word “Union” in its name. Of course at the time, “Union” had several meanings, but not “labor union,” which were the initiators behind the holiday of Labor Day. At the time, this particular company did not have an organized labor union, but decades later, calls for one, would serve as the undoing, or dare I say, un-stitching of the Union Knitting Mills—one of Frederick’s largest employers from 1887-1957. The Beachcombing Industrialist I have always had an incredible love of the beach, and am not alone. Stories of early industrialist who loved the shore have interested me as well. I have made trips to Jekyll Island, Georgia where the world’s wealthiest families vacationed— most notably the Morgans, Vanderbilts and Rockefellers. In fact, beer-brewing legend, Adolph Coors, escaped the Rockies and Colorado to spend time at Virginia Beach. Unfortunately, he chose to take his life here in June of 1929 by jumping out of a window of the Cavalier Hotel at which he was lodging. Thirteen years of the Prohibition had taken its toll on the legendary beer-maker from Germany. John Llewellyn Johnson just plain loved the ocean. He was one of the leading citizens of our town at the turn of the 19th century. He not only made an impact here in western Maryland, but also played a role in the early development of Maryland’s pride of the eastern shore, the aforementioned Ocean City. John L. Johnson had no connection to the Frederick family connected to our state’s first governor. He was born just a few days prior to the summer solstice, on June 18th, 1856 in Philadelphia. His father, John Porter Johnson, was a cooper by trade and veteran of the Civil War. John’s mother was a woman named Ellen Gillmore Johnson, and like her husband, is said to have come from old families associated with New Jersey. I learned from John L. Johnson’s biography found in Volume II of Williams & McKinsey’s "History of Frederick County, MD" (1910) that the one-day Frederick resident had grown up in “the City of Brotherly Love.” Apparently, he was sent to Massachusetts in his youth and learned knitting in a knitting mill under his uncle. Upon reaching adulthood, John went to Bristol, PA at which place he took charge of the aptly named Bristol Knitting Mills. After some time, Johnson returned to Philadelphia and worked under the employ of Blood Brothers as an overseer. Later, he would be employed by E. Sutro & Company. His next career move would come in 1887, at which time he would be brought to Frederick, Maryland to head an endeavor concocted by some of the towns leading business entrepreneurs. This was the Frederick Seamless Hosiery Company. The following narrative can be found online as part of the Maryland Historical Trust inventory of historic properties (NO FHD-1300): The Frederick Seamless Hosiery was founded in 1887 by five Frederick businessmen, David Lowenstein, Thomas H. Haller, John Baumgardner, George H. Zimmerman, and M.E.Getzendanner with $5,000 in capital. It was first established in the four-story Etchison building at 34-36 East Patrick Street and the primary product was men's half hose. Soon the business outgrew the building and in 1888 the partners bought the site of the former Vulcan Iron Works at 340 East Patrick Street and began building a new factory. In 1889, the Frederick Seamless Hosiery was reorganized and renamed The Union Manufacturing Company and took up residence in the newly constructed building.

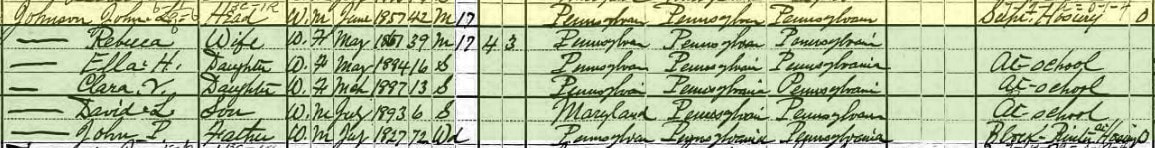

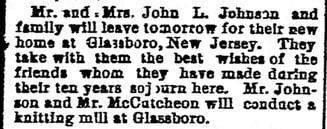

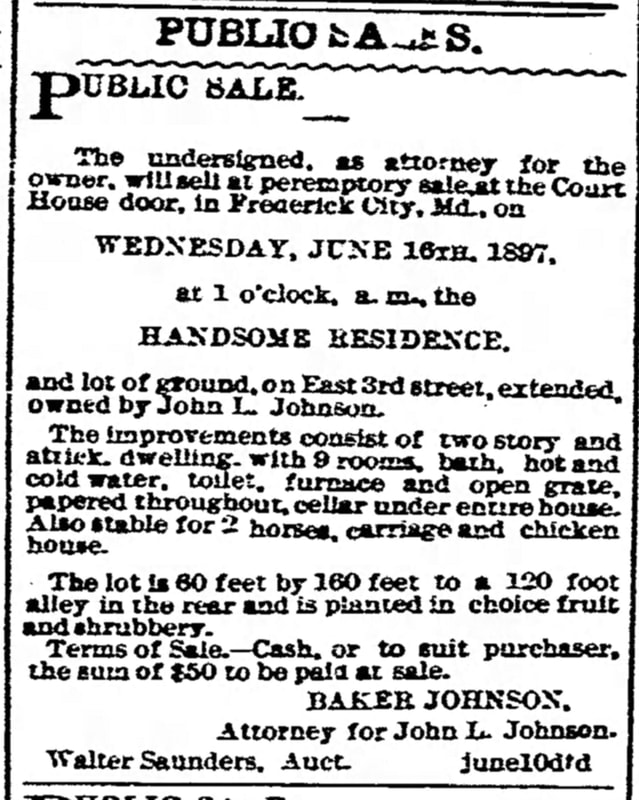

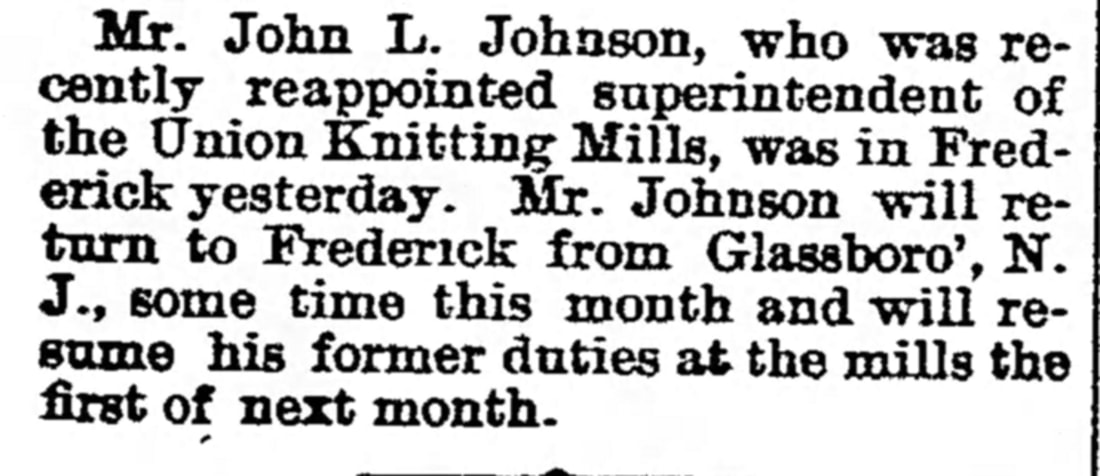

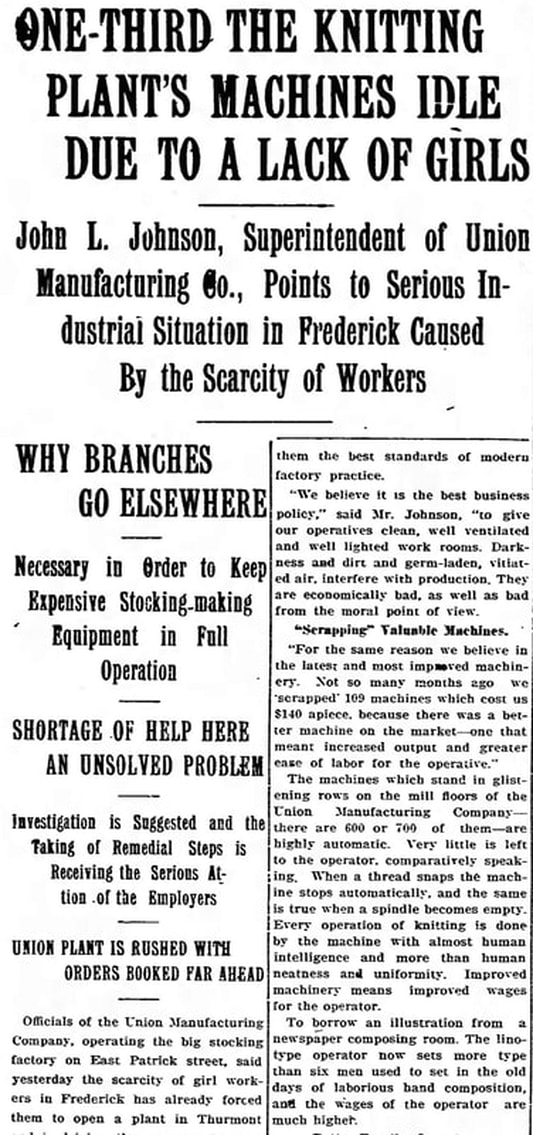

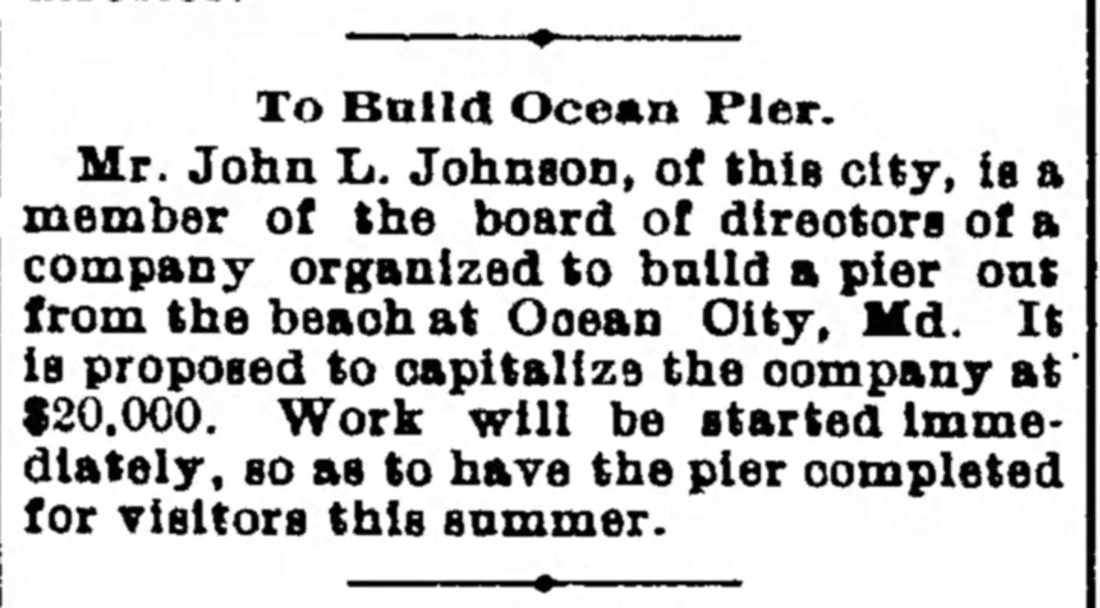

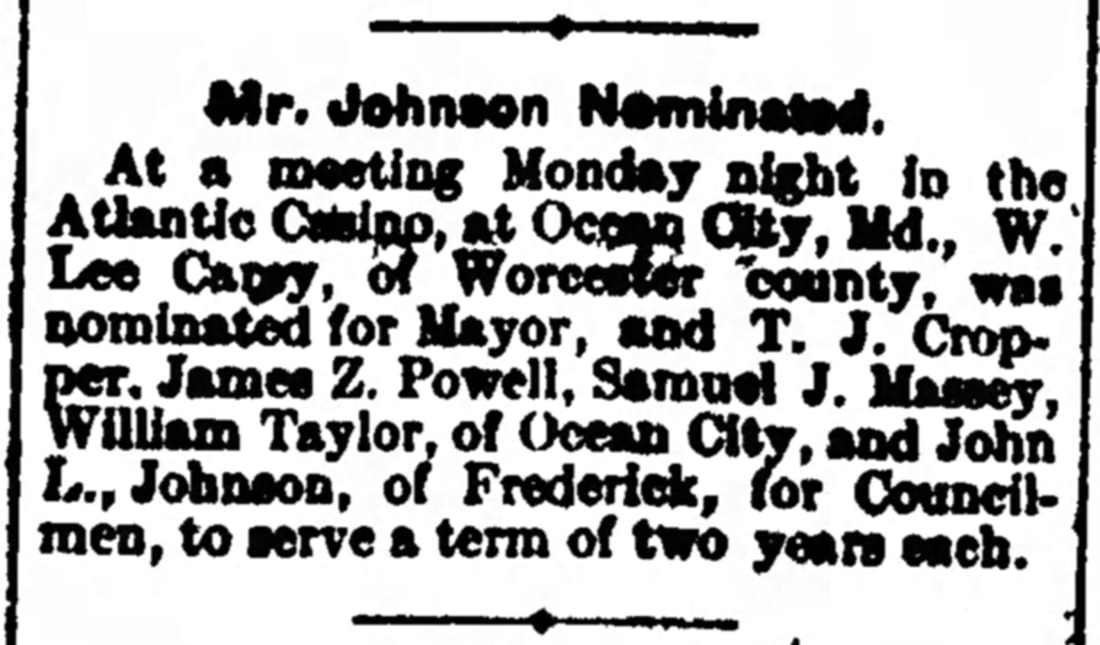

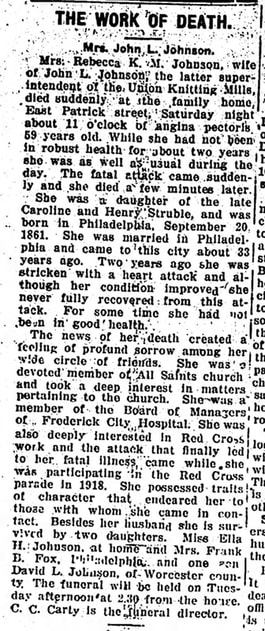

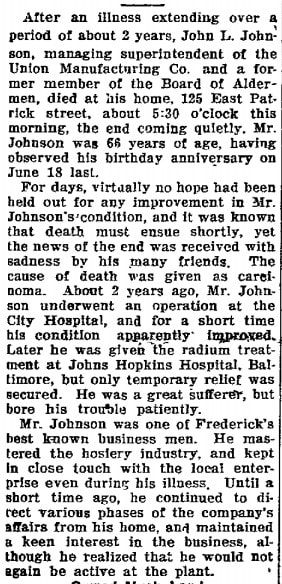

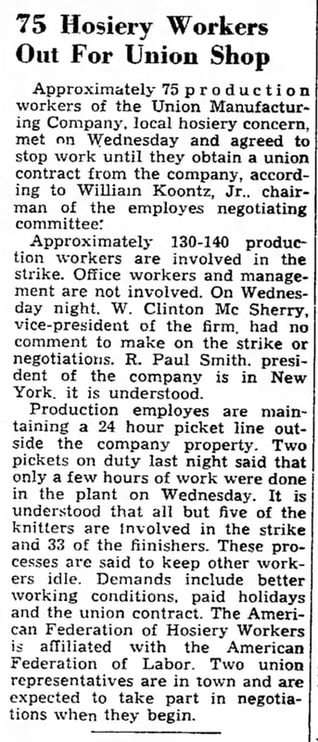

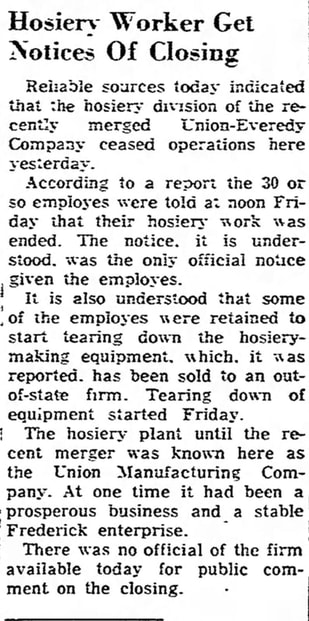

As previously stated, John L. Johnson was made managing superintendent of the firm, and also became a shareholder. The Williams & McKinsey History of Frederick states that “much of the success achieved is due to the great ability with which Mr. Johnson has discharged the duties devolving upon him.” The biography goes on to say: “He has been engaged in the knitting business all his life, and has thoroughly mastered all the details of that industry. He is strictly a self-made man, and owes his success in life to close application to business, and to his sober, temperate habits. Mr. Johnson has not given all his time to the knitting business, but has been active along other lines. He has always been a stanch supporter of the Republican party and, at the municipal elections in June, 1910, was chosen a member of the board of Alderman of Frederick City which is strongly Democratic. Fraternally, he is a member of Columbia Lodge, No. 58, A.F. and A.M.; Enoch Royal Arch Chapter, No. 23; Jacques De Molay Commandery, No. 4, Knights Templar, of Frederick; LuLu Mystic Shrine, of Philadelphia; Frederick Lodge No. 684, Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks; the Manufacturers Club of Philadelphia; and the Sons of the American Revolution. John L. Johnson was married to Rebecca Kay Maree Struble, of Philadelphia, Pa. They have three children: Ella H., Clara V., and David L. In religion, he is a member of the Episcopal Church. On their move from Philadelphia, the Johnson family first took up residence on a lot sold to them by business partner David Lowenstein. This was on East Third Street extended. Interestingly, I found news clippings that reported that Mr. Johnson had actually left Frederick with his family in 1897 and moved to Glassboro, NJ, where he and a partner opened a like-knitting operation to the Union Knitting Mills. During the spring of 1897, the Glassboro factory opened with twenty new machines and it’s said the female workers became very efficient with the machines. The factory did well and even gave their employees a week paid vacation, which at the time was very rare. This was a trademark of John L. Johnson's management style.  Wm O. McCutcheon (1858-1952) Wm O. McCutcheon (1858-1952) Ironically, the partner was destined to make a name for himself in the annals of Frederick manufacturing history, but not in the production of clothing but in the realm of canning, but would not occur until the late 1930s. He was Johnson’s brother-in-law, the husband of his wife’s sister, Annie. His name was William Oscar McCutcheon, also a native of Philadelphia and an experienced stocking weaver. A few years prior, Mr. and Mrs. Johnson encouraged the McCutcheons to move to Frederick and put William's talents to work for the Union Knitting Mills. Both families would leave for Jersey, but would eventually return to the town of clustered spires.  McCutcheon's Apple Press McCutcheon's Apple Press John L. Johnson came back in 1899 and took up residence on E. Patrick St. Mr. McCutcheon and family moved to Barnesville, Ohio where he managed a knitting mill there. The McCutcheons would return to Frederick where William managed the Colt-Dixon Canning Company for decades. In 1938, he would locate a used apple cider press on Wisner Street, exactly across from the Union Knitting Mills. Here, along with his son Robert and daughter in law Helen, he would found what would become McCutcheon Apple Products, an operation that continues to thrive today, generations later. The first decade of the new century saw measured growth under Johnson's leadership, however problems would arise at the beginning of the second decade. In particular, 1911 and 1912 would be trying times as Johnson and the knitting operation experienced a shortage of workers. This prompted the company to establish satellite operations of the Union Knitting Mills in Emmitsburg and Thurmont. Johnson's Personal Life A good manager always makes time to “recharge” his or her batteries by partaking in times of rest and relaxation. Mr. Johnson made countless trips to Ocean City. He also seems to have encouraged co-management and other Frederick business leaders to do the same as I found many clippings of the Johnsons entertaining guests at their beach cottage. I also presume that Johnson had a hand in designing the annual beach outings for the Union Company’s employees. A lasting tradition included an annual trip to Tolchester Beach on the eastern shore of the Chesapeake, located west of Chestertown in Kent County. Johnson spent enough time in Worcester County as to have been elected to the city council of Ocean City in 1908. In previous years he had been part of a board which planned the building of the famed Ocean City pier. This project was completed in 1907 and had a major effect in encouraging visitors and business to the beach resort. Rebecca Johnson died in 1920. Like her husband, she had also served her community well as one of the early Board of Managers of the Frederick City Hospital. Mr. Johnson had her buried in a lot located in Area Q (`Lot 182). Here, the Johnsons had earlier buried an infant son (John Llewellyn Johnson, Jr.) in 1892, and John's father in 1905. John L. Johnson found himself in poor health at the time of Rebecca’s death. He was diagnosed with cancer and underwent progressive treatments for the day including radium treatments. He died at home a week after celebrating his 66th birthday on June 27th, 1922. His body would be laid to rest in Mount Olivet two days later. The Legacy of Union Manufacturing And what became of the company Johnson labored for over a 35 year period? We can return to the Maryland Historical Trust report for the proverbial “rest of the story:” As the Great Depression set-in, the knitting mill found itself in good stead having purchased new rayon knitting machines. By 1935, rayon stockings with the seam running up the back of the leg were becoming the fashion so the factory continued to prosper and the building expanded to keep pace. Then, in 1937, Dupont Industries successfully developed nylon thread. The Union Manufacturing Company had been a good customer of Dupont's in the past and was offered a chance to experiment with the new fiber that same year. After several days of trial and error, in the spring of 1937, the Union Manufacturing Company produced the first nylon stocking in the world. The new stocking was a hit and soon the knitting mill was turning out over one million pairs of women's stockings annually. Hose from the Union knitting mill was being sold all over the world under the brand names of Wonder Hose and Ever Wear. Unfortunately, the success did not last. Following World War II, fashions changed again and the seamless variety of stocking was back in style. The company was caught unprepared, they did not have the machinery to produce the new kind of hose. Business dropped off and workers were let go and hours cut back. In 1959 the Union Manufacturing Company and another local business, the Everedy Company, merged to form the Union-Everedy Co. After the merger, Union stopped making hosiery, and the knitting machines were sold. In 1962, Meadows Van and Storage purchased the building  A fuller picture of the demise of the company in the 1950’s can be found in a wonderful history compiled in 1997 by authors Joseph Ford, Lynne Wells and Melissa Conroy and entitled: "The History of the Union Manufacturing Company from 1887 to 1957" and published by Fredericktowne Printing and Graphics. The authors say that there was “an external force that caused the tensions to erupt. In 1952, the American Federation of Hosiery workers approached the workers and attempted to organize them. ‘The salesmen told us they could sell hosiery if it had a union label,’ said (former employee ) Mrs. Grace Baker. It made sense to some of the workers, who believed that the company work conditions were due to decreased profitability arising from the inability to market the factory’s hosiery. Yes, it made little sense to the management who still believed they were doing the community a favor by continuing business in spite of decreased profitability. The tension between management and the workers came as a surprise to many who had seen the relationship between the two in a positive light. A Norwegian visiting the factory had once commented, ‘The most striking feature about American manufacturing is its mass production and the second thing is the relationship between people in the mill…you can’t have high efficiency without the relationship…This cooperative spirit between management and labor is really outstanding here.’  John Lewelynn Johnson can be credited with setting the early tone for this endeavor and creating a corporate culture that bred efficiency and high quality of product. Things turned turbulent in March, 1952, thirty years after Johnson’s death. Employees went on strike, one of the first work demonstrations in Frederick’s history, not to mention one of the largest. This also created a problem for the city as 27 police officers had to be assigned to the scene, culminating with the mayor requesting that the Union Manufacturing Company’s management close down the plant until the strike was settled. The strike is said to have ended quietly, but the damage had been done as the relationship between management and laborers would never be the same afterwards. The company limped forward for another seven years, however the end came to producing hosiery in mid August of 1959. Employees helped pack up the machines and after a 72-year run in stockings (pun intended), the knitting operation John L. Johnson helped built went quiet. Labor Day and the Union Knitting Mills no longer were connected.

2 Comments

9/2/2019 09:22:30 pm

I enjoyed this article. I didn't know much about it. My Father and Grandfather made the boxes for the hose and stockings. This was the New Citzen on East Patrick . It once was a news paper but later was a box manufacturing plant. We have met before in the cemetery on your walk in May. George Schroder, my father when the New Citizen closed its box making that is when he went to work at the news post. I remember when they made boxes, The cardboard was made at the paper mill in Hall Town.West Va. Many pretty paper samples I remember were there to be picked to cover the boxes. There were Holiday, seasonal, and other designs to use to cover the hosiery boxes. I still have a folder with some of the paper. I used the scraps of paper.for play

Reply

Rebecca McCutcheon Griffin ( Becky)

8/11/2023 07:31:51 pm

I knew some of the history of my grandfather, William O McCutcheon, and his connection and relationship to John L Johnson. I also knew some of the history of the Union Knitting Mill in Frederick, Md.. We are having a McCutcheon family reunion on Saturday, August 12,2023. I am printing the entire article to show to the relatives. Hopefully that is permissible and it will encourage many to read more of your "Stories in Stone". Thank you

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed