|

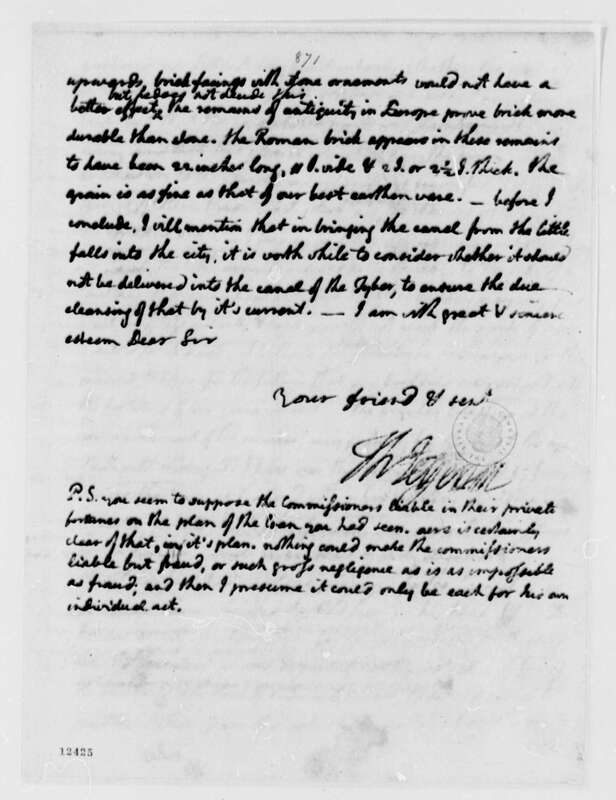

Hopefully I’ve piqued interest with the unorthodox title above. Living here in Frederick, Maryland, most residents are familiar with the initials “T.J.” and who they belong to. Yes, the man who unknowingly lent his name to not only a local high school (my alma mater) and middle school, but also a thoroughfare through an estimated 85% of our town’s physician offices and related medical services. I’m talking, of course, about Thomas Johnson. Mr. Johnson was one of Maryland’s top heroes of the American Revolution period, and became the state’s first elected governor. His resume is quite impressive, and the above named legacies are fitting because they are located on land Johnson had purchased in 1778. I wrote a piece on Gov. Thomas Johnson, Jr. back in October 2019, marking the 200th anniversary of his death. My focus this week is not on Thomas, but I wanted to make special mention of one of his eight children, Ann Jennings (Johnson) Grahame, born in Annapolis in 1759. In addition to being his oldest daughter, biographer Edward S. Delaplaine claimed that she was her father’s favorite. Thomas Johnson had five of eight children reach adulthood, one being the fore-mentioned Ann. As for Ann Jennings (Johnson) Grahame, many may have a familiarity with this woman, but likely more because of her home, rather than a particular deed or accomplishment achieved during her lifetime. Ann, and husband Major John Colin Grahame, are responsible for building the mansion known as Rose Hill Manor in the mid-1790s. The story goes that Anne’s father gave the newly married couple an amazing wedding gift in 1789—the 225-acre parcel formerly known as Rose Garden. Thomas Johnson also “bankrolled” the construction of the magnificent manor house. In return, Thomas, who had recently lost his wife, came to live at Rose Hill for his final 25 years. (He had previously lived just up the road at a plantation named Richfield.) Major Grahame died in 1833, and Ann would live another four years until spring, 1837. Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht made the following entry in his diary on May 5th, 1837: “Died on Wednesday last 3rd instant in the 69 years of her age, Mrs. Ann J. Grahame widow of the late Major John Grahame and daughter of the late Governor Thomas Johnson. Buried on the Protestant-Episcopal graveyard.” This locale was also known as All Saint’s Burying Ground, between Carroll Creek and East All Saints Street. Sometime between 1854 and 1913, Ann’s remains would be reinterred here in Mount Olivet in Area A/Lot 2. A fine monument memorializes her, although the death date carved in stone reads 1835 instead of 1837. Our cemetery files agree with Engelbrecht’s death date, however his math was off by ten as Mrs. Graham was 79 years of age, not 69. Well that takes care of explaining a fraction of my puzzling story title. Since we’ve now established who one T.J. is, now it’s time for the “other,” as these two men personally knew each other during time spent together serving in the Continental Congress and fight for Independence back in the 1770s. Proof of their relationship in later decades exists in the form of a letter received by Thomas Johnson in March 1792 from the other T. J. The contents spoke to Mr. Johnson’s work as one of the commissioners chosen to oversee the laying out of the country’s new capital, the District of Columbia.

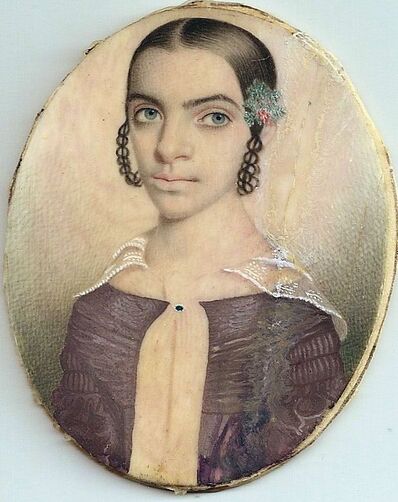

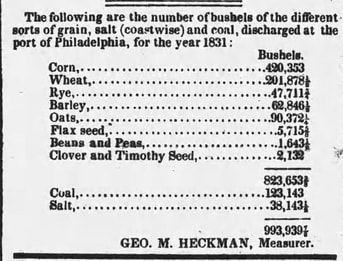

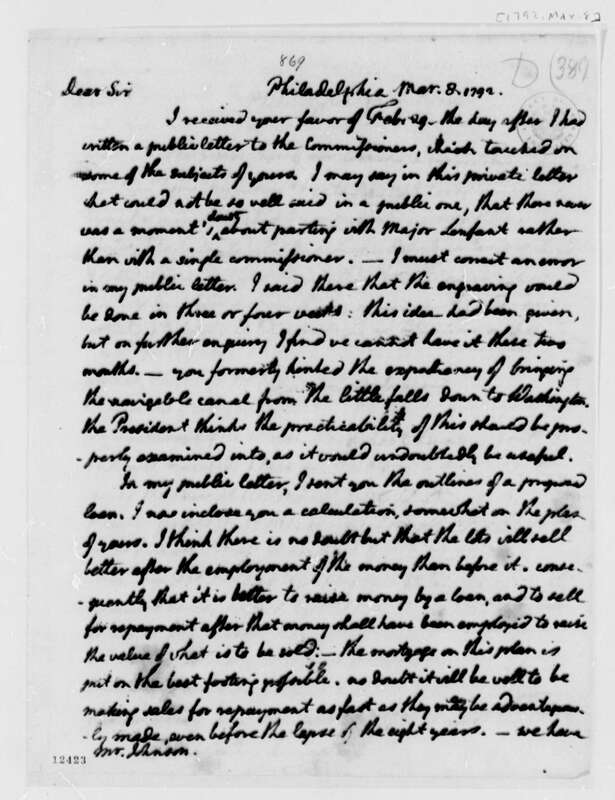

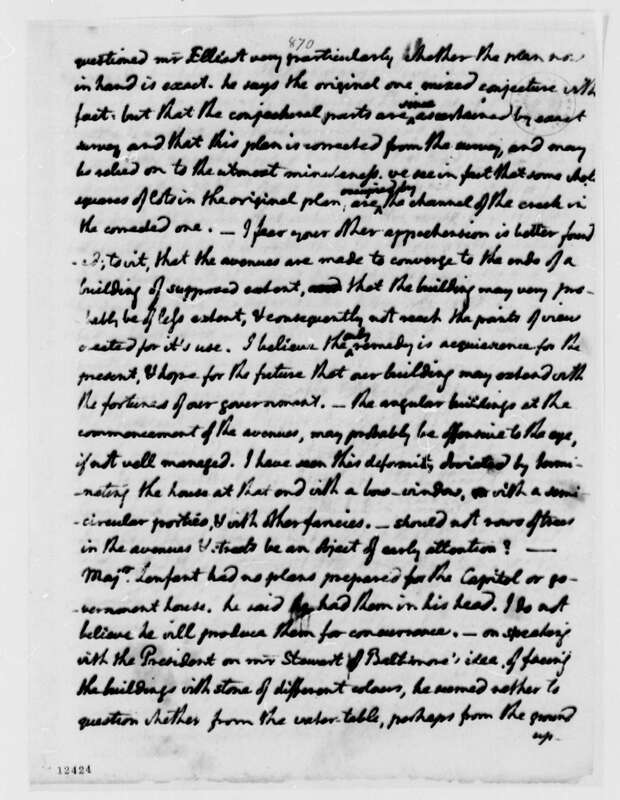

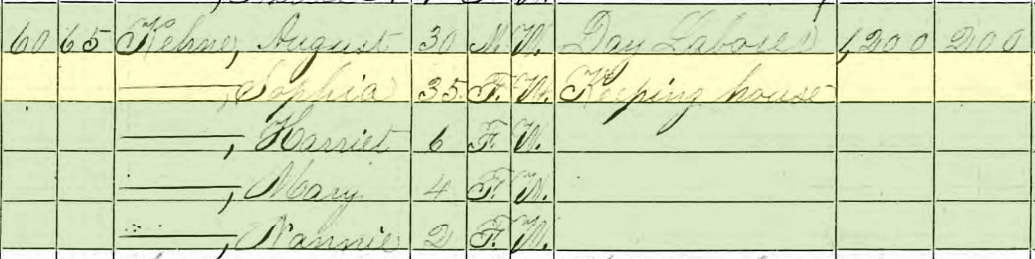

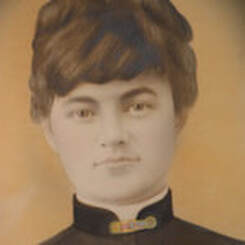

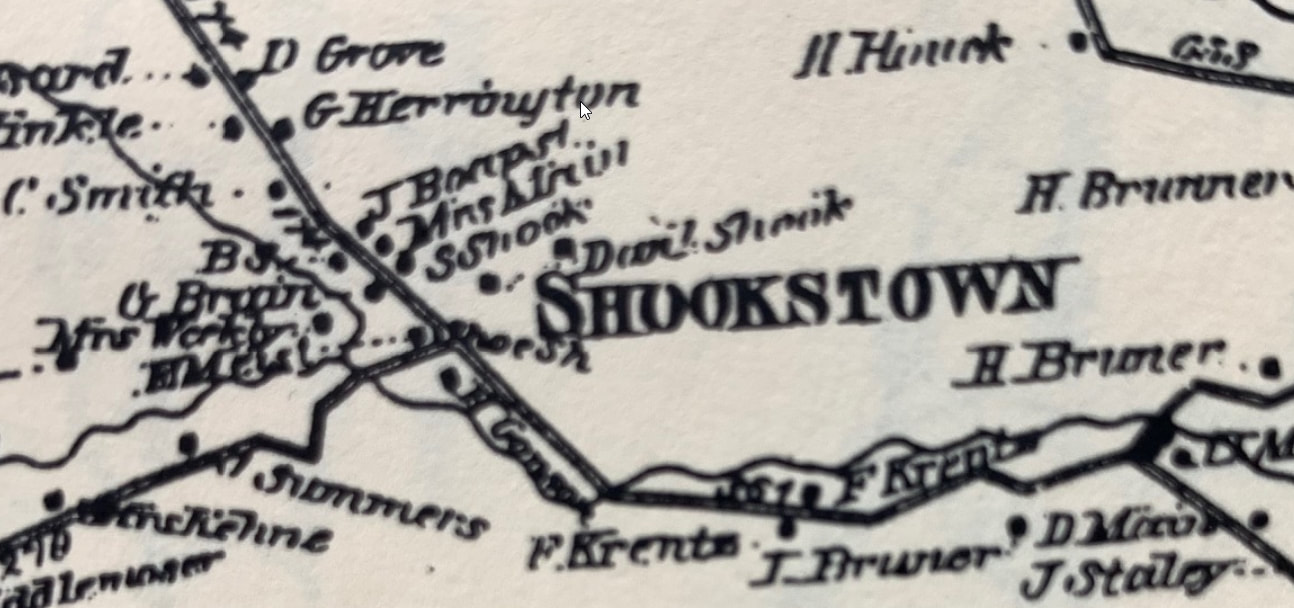

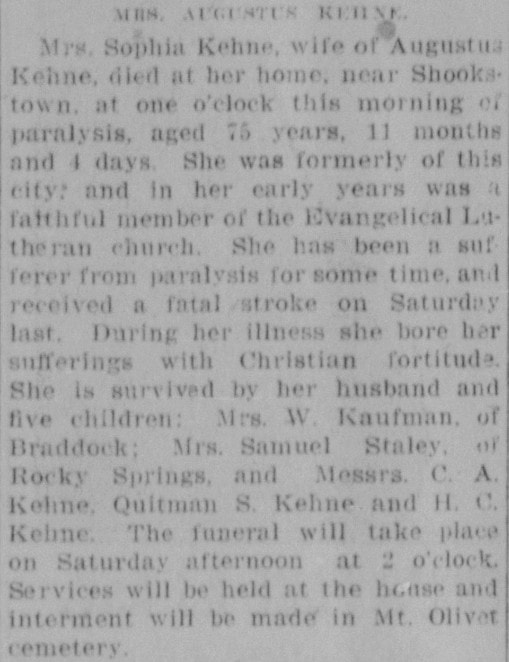

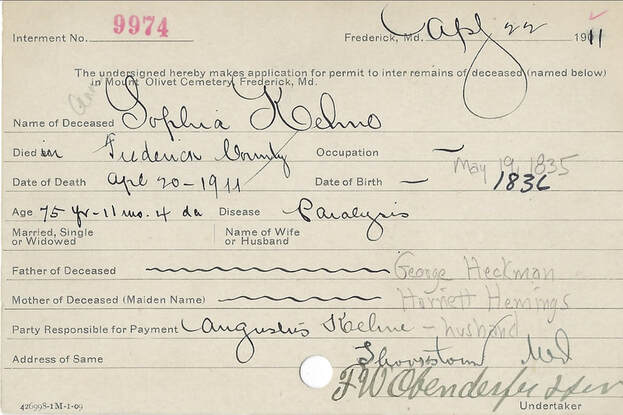

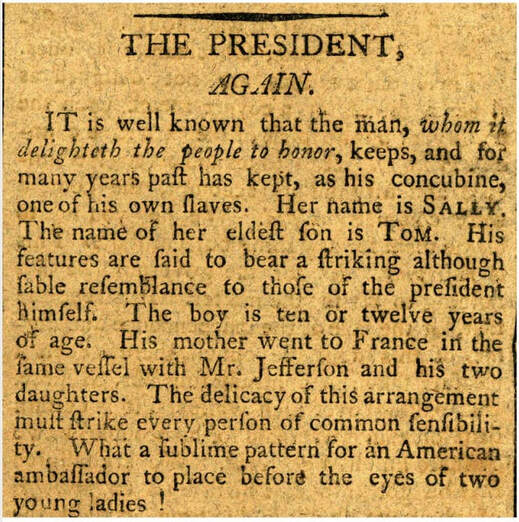

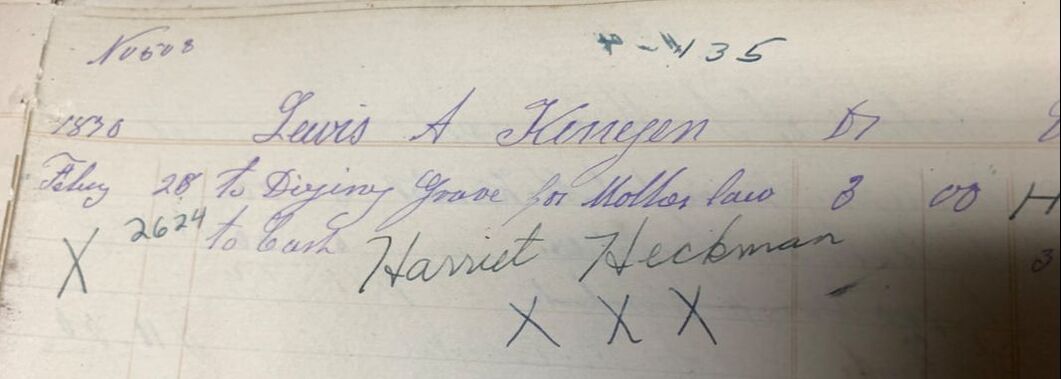

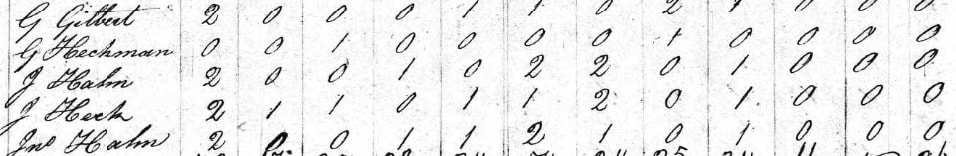

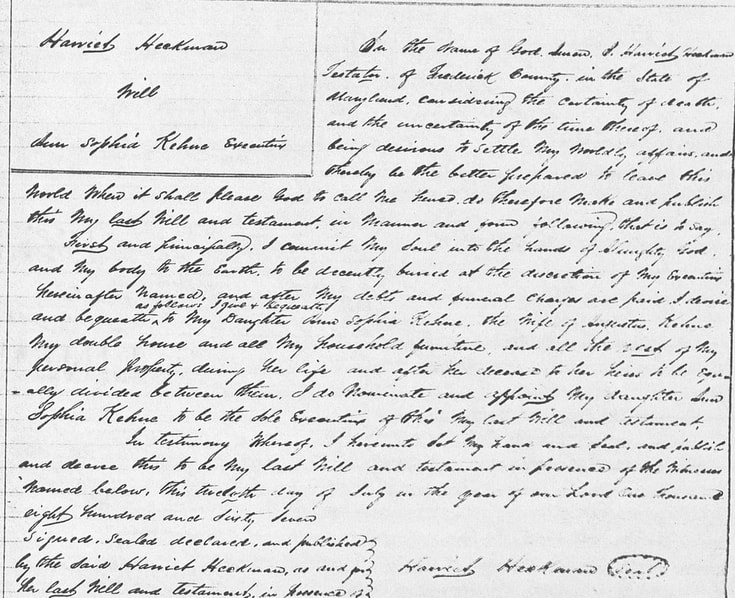

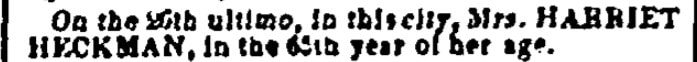

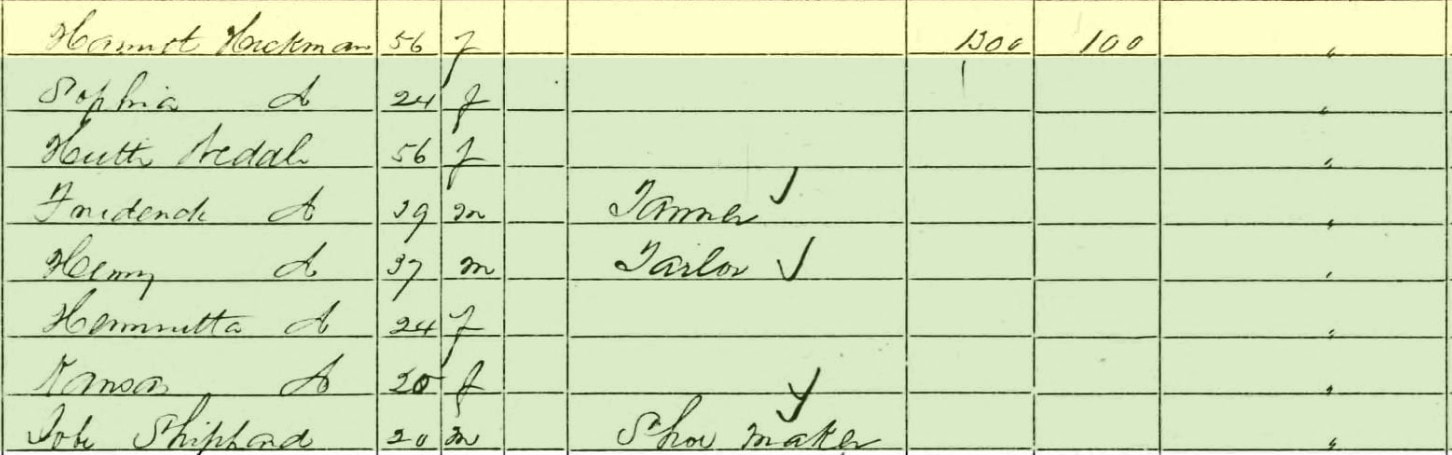

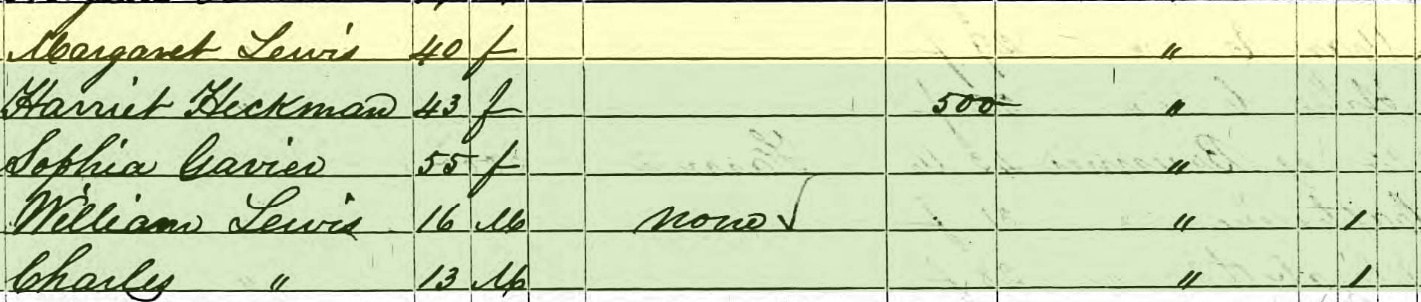

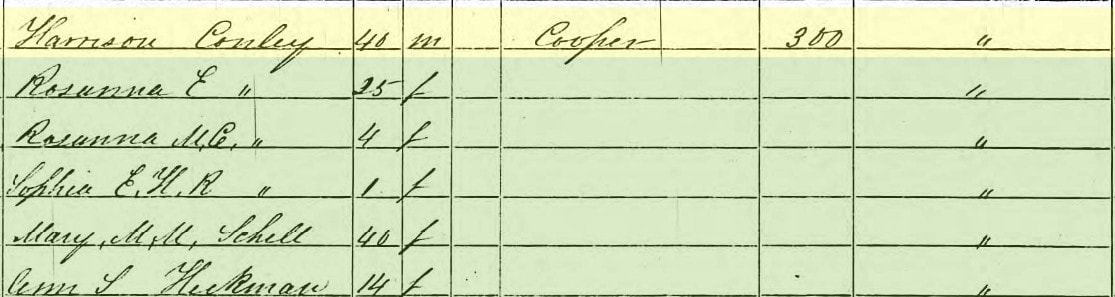

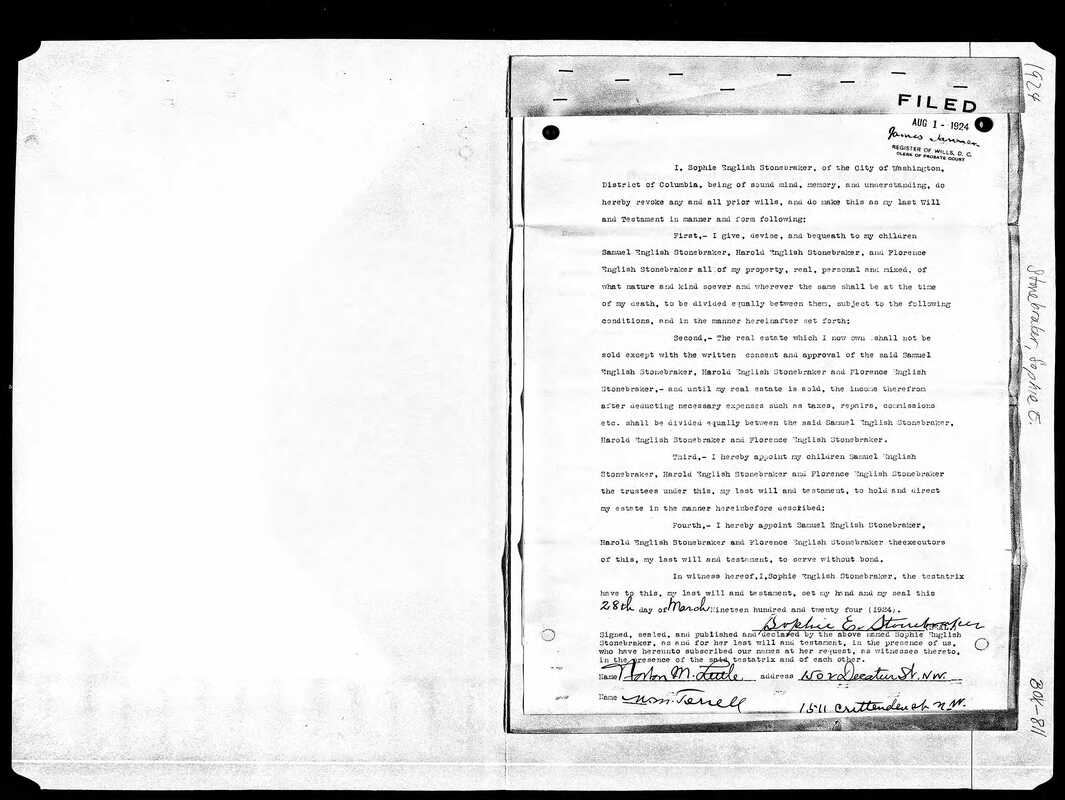

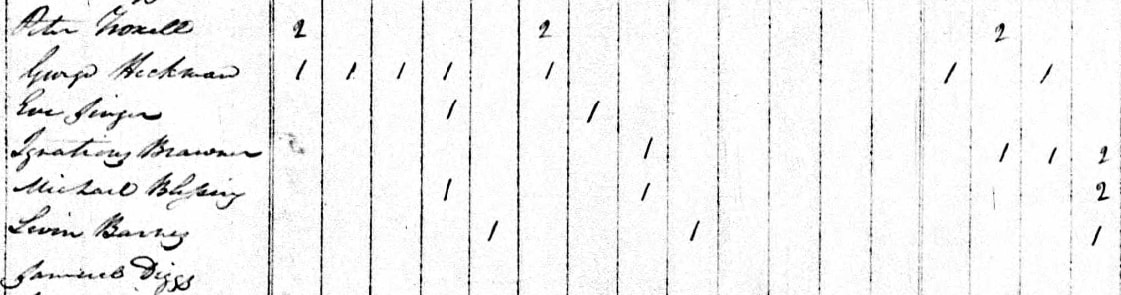

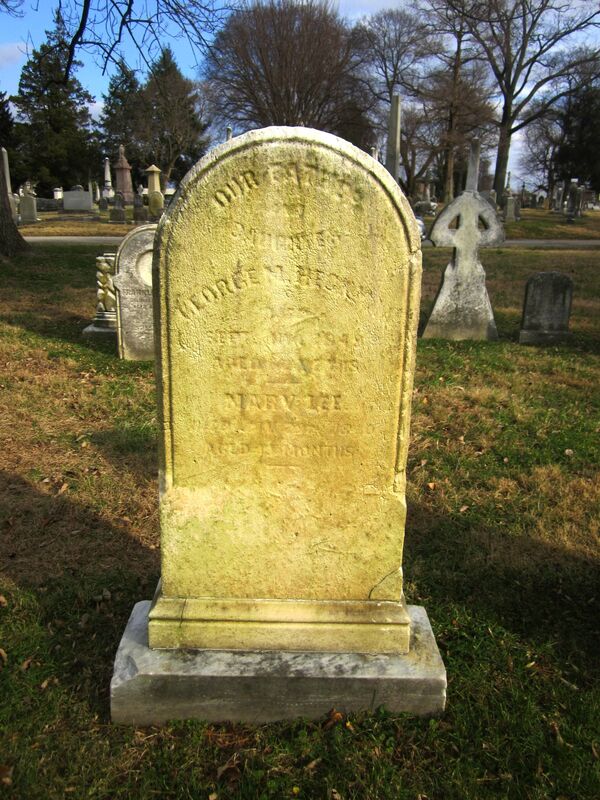

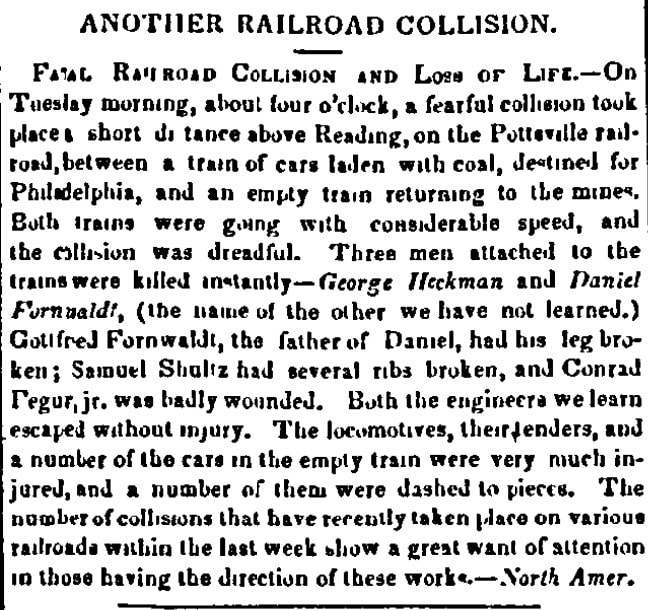

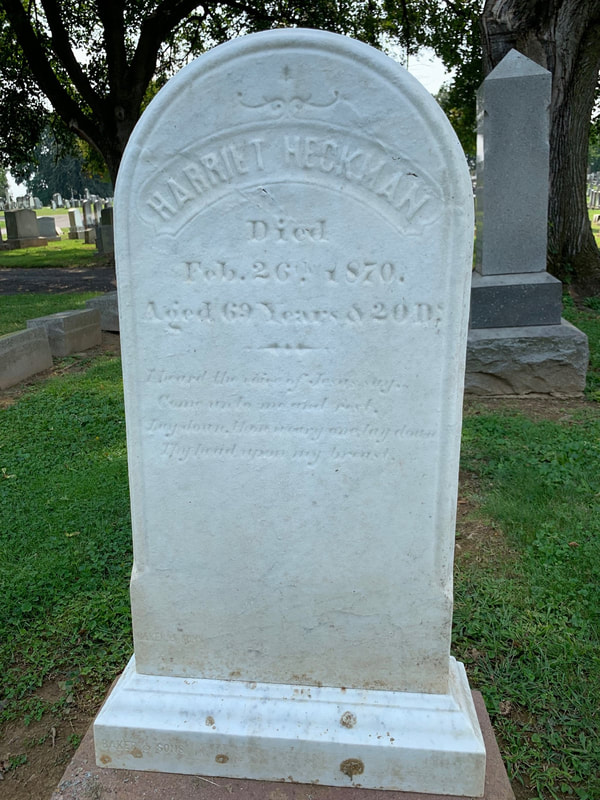

Of course I’m talking about the immortal Thomas Jefferson, who at this time was serving as Secretary of State under first president George Washington, a known close friend of Thomas Johnson. Interestingly, I learned that our (Frederick) T.J. was originally given consideration by Washington to serve as his Secretary of State in 1793. Johnson would be offered this position by Washington, himself, two years later, after the resignation of Edmond Randolph. Johnson had stepped down from a position as an associate justice on the U.S. Supreme Court late 1793 and would respectfully decline the position due to his own concerns with declining health. Wives and Daughters Both T.J.s were widowed early, Thomas Johnson in 1794 after the death of wife Ann Jennings, and Thomas Jefferson in 1782 when wife Martha Wayles Skelton (b. 1748) passed, likely due to complications tied to the birth of her final child, Lucy, who would eventually die at age two. Two other children of Thomas and Martha Jefferson also died in infancy (Jane in 1775 and Peter in 1777). The couple did have two daughters who lived into adulthood: Martha “Patsy” Randolph (1772-1846) and Mary “Polly” Eppes (1778-1804). So I recently received an interesting phone call from my longtime barber, Lawrence Jesse, and wife Susan Reeder Jesse. Apparently a family friend of theirs dabbles in genealogy, and offered to do some family tree work for them. Well, while researching back through Susan’s lineage, the researcher stumbled upon a very curious and interesting find in regard to Susan’s mother’s family, the Kehnes. It appears that Susan’s GG Grandfather, George Dallas Kehne (1850-1931), had a brother named Lewis Augustus Kehne (1840-1920). Both Kehne brothers emigrated to America (and Frederick, Maryland) in the early 1840s, coming with father Charles Frederick Kehne and mother Marie Delong from the highly contested Alsace region on the France and Germany border. Of chief interest here is the wife of Frederick Augustus Kehne, one Ann Sophia Kehne, born May 19th, 1835. As the researcher dug a little further into information on this woman who made her home in Shookstown, northwest of today’s City of Frederick, something peculiarly interesting came to light. Numerous books, as well as genealogical sources and family trees found on the internet showed that Ann Sophia Kehne was the granddaughter of our third U.S. President. That’s right, T.J., Thomas Jefferson! Best of all, for me, Ann Sophia Kehne is buried in Area H of Mount Olivet. Susan Jesse went on to explain to me that her family researcher had found something even better—Ann Sophia’s mother is also buried here in the cemetery. I soon learned that mother and daughter are buried in the same plot—Area H/Lot 190. So, if true, this would make Ann Sophia Kehne the daughter of one of the earlier mentioned Jefferson daughters, right? However, I seem to recall telling you that Mary “Polly” Eppes died in 1804, so I can rule her out. Martha “Patsy” Randolph (1772-1846) would have been 63 years old in childbirth with Ann Sophia in 1835, but that seems medically impossible. Hold the phone! I quickly learned that these two ladies are buried in Virginia, next to their father in Monticello Graveyard. So how could a woman buried in Mount Olivet’s Area H/Lot 190, 132 miles away from Monticello, possibly be the daughter of the president? Talk about stumping the band? I was perplexed as Ann Sophia's mother, a woman named Harriet Heckman (1801-1870), would be the object of my new research quest. I quickly learned that I was not alone, as others have been trying to piece together this puzzle for well over a century. I was able to study a few elements from the "back end" of this Harriet’s life with a firm connection to daughter Ann Sophia, and residency here in Frederick. She first appears in the 1850 census, living in Frederick City. My assistant Marilyn Veek found Harriet’s name in land and estate records but not much more is known of her humble, or not so humble, life. I could find nothing on her early days such as a birth/ baptismal or marriage record, maiden name, parents or siblings. Harriet Heckman's story seems to ooze secrecy— and was this by design? Whatever the case, I can’t definitively give you a final answer on her true life story from beginning to end at this time, but I can share facts, and I confidently feel that there is at least a 50% chance possibility that this Harriet Heckman could well be “The Other T.J.’s Other Daughter.” Now let’s explain my use of “other daughter,” but before I do, maybe this would be a good time for you, the reader, to take a brief intermission. Walk around, check emails, grab a drink or a snack to eat, meditate, because I have just thrown at you an intriguing new, local history possibility (for Mount Olivet and Frederick) coupled with a great deal of genealogical data. Next up, I prepare to drop quite a bomb on you, so go ahead and take a break as I’ll wait. See you back here in a few. Harriet Heckman So who is this woman named Harriet Heckman, mother of Ann Sophia (Heckman) Kehne and buried in Mount Olivet’s Area H/Lot 190, exactly fifty yards, and within plain eyesight, of Ann Jennings (Johnson) Grahame’s grave monument over in nearby Area A? Our records give us birth and death dates on Harriet, but nothing more. As for Ann Sophia, her original interment card from 1913 includes vital dates and the names of her parents, but this latter key piece of information was not written on the card until decades later, and in the hand of our cemetery superintendent, J. Ronald Pearcey. You can clearly read above that which I saw a few weeks back in pulling this card— the names of George Heckman and Harriet Hemings, both written in pencil, along with a corrected birth date. Back to Ron Pearcey, who recently celebrated his 55th anniversary as an employee of this cemetery. His mind is sharper than most, however he can’t quite remember the circumstance in which he came upon this information. He is pretty sure a cemetery patron or family member gave it to him because it is written in his own handwriting and in pencil. He wonders if it was former genealogist Margaret Myers, a local legend in the field, who passed away back in 2009. Margaret contributed much to enhancing our records, but was she involved in this quest for this “Lost Ark of the Monticello Covenant? Several biographies on Thomas Jefferson state that Martha Jefferson made a poignant request of her husband in her dying days. So that her children would not grow up with stepmothers, she had asked Thomas Jefferson to never marry again, and he never did. Her request has been said to have been attributed to her own disagreeable relationships with her step-mothers. Of particular note here, Martha had been married previously and widowed. Now at the time of her passing, she was 33, and Jefferson was 39. Although Thomas Jefferson never married again, it’s known that he had additional children after Martha’s passing. The “baby-momma,” or mother, of these children was a mixed-race slave at Monticello named Sally Hemings. Sally originally came into Jefferson’s life as part of the dowry gained through marrying Martha. In fact, Sally Hemings also shared common blood with white counterpart Martha Jefferson. Both women could claim a common father, John Wayles (1715-1773), which made them biological step-sisters. Sally Hemings was born about 1773 to Elizabeth (Betty) Hemmings (1735–1807), a woman also born into slavery. Sally's father doubled as their (Sally and Betty’s) master John Wayles. Betty's parents included another enslaved woman, a "full-blooded African,” and John Hemings, an English sea captain. So do we at Mount Olivet have yet another woman and generation of this family with mixed blood through a slave and master pairing? Claims that Thomas Jefferson fathered Sally Hemings's children have been debated since 1802. That year, a gentleman named James T. Callender, after being denied a position as postmaster, alleged Jefferson had taken Hemings as a concubine and fathered several children with her. In 1998, a panel of researchers conducted a Y-DNA study of living descendants of Jefferson's uncle, Field, and of a descendant of Sally Hemings' son, Eston Hemings. The results, released in November 1998, showed a match with the male Jefferson line. Subsequently, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation formed a nine-member research team of historians to assess the matter. In January 2000 (revised 2011), a report concluded that "the DNA study ... indicates a high probability that Thomas Jefferson fathered Eston Hemings." The same report by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation also concluded that Jefferson likely fathered all of Heming's children listed at Monticello. A high degree of controversy surrounded this subject and how the results were interpreted. In July 2017, the T.J. Foundation announced that archeological excavations at Monticello had revealed what they believe to have been Sally Hemings' quarters, adjacent to Jefferson's bedroom. In 2018, the this same group said that it considered the issue "a settled historical matter." Since the results of the DNA tests were made public, the consensus among academic historians has been that Jefferson had a sexual relationship with Sally Hemings and that he was the father of her son Eston Hemings. Sally Hemings' documented duties at Monticello included being a nursemaid-companion, lady's maid, chambermaid, and seamstress. It is not known whether she was literate, and she left no known writings. She was described as very fair, with "straight hair down her back". Jefferson's grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, described her as "light colored and decidedly good looking." She is believed to have lived as an adult in a room in Monticello's "South Dependencies," a wing of the mansion accessible to the main house through a covered passageway. One of the key informants on the subject was another alleged “lovechild” of Sally and Thomas Jefferson named Madison Hemings. In 1873, this man’s brief memoir was written and published. Excerpts appeared in newspapers across the country. According to Madison, his mother's (Sally's) first child, named Tom, died soon after her return from Paris in 1789. He notes that Sally Hemings gave birth to six children after her return to the United States and their complete names are, in some cases, uncertain: Harriet Hemings (October 5, 1795 – December 7, 1797) Beverley Hemings, possibly William Beverley Hemings (April 1, 1798 – after 1873) Daughter, possibly named Thenia Hemings after Sally's sister (born in 1799 and died in infancy) *Harriet Hemings [II] (May 22, 1801 – Unknown) Madison Hemings, possibly James Madison Hemings (January 19, 1805 – 1877) Eston Hemings, possibly named Thomas Eston Hemings (May 21, 1808 – 1856) Jefferson recorded slave births in his Farm Book. Unlike his practice in recording births of other slaves, he did not note the father of Sally Hemings' children. Sally Hemings never married. As a slave, she could not have a marriage recognized under Virginia law, but many slaves at Monticello are known to have taken partners in common-law marriages and had stable lives. No such partnership of Hemings is noted in the records. She also kept her children close by while she worked at Monticello. According to Madison, while young, the Hemings children "were permitted to stay about the 'great house', and only required to do such light work as going on errands.” At the age of 14, each of the children began their training: the brothers with the plantation's skilled master of carpentry, and Harriet as a spinner and weaver. The three boys all learned to play the violin, which Jefferson himself played. Harriet Hemings, oldest surviving daughter of Sally Hemings does not have a known burial place—or does she? Harriet Hemings So let’s zero in on our mystery women named Harriet, both at Monticello and here in Mount Olivet. Information is known on Harriet Hemings’ early life, but not her later life. As I said, we know of Harriet Heckman’s later life but nothing of her younger life. This is a clue to me that there is a possibility, not so far-fetched, both of these "Harriet" puzzle pieces may fit together. In 1822, Harriet Hemings’ older brother, Beverley, age 24, "ran away" from Monticello and was not pursued. His destination was Washington, DC. Harriet Hemings, then 21, followed in the same year, apparently with at least “tacit” permission from her parents, Sally and Thomas Jefferson. The plantation overseer, Edmund Bacon, later stated that he had given Harriet $50 ($1,067 in current dollars) and put her on a stagecoach to the North, presumably to join her older brother in Washington, DC. In his memoir, published posthumously, Mr. Bacon said Harriet was "near white and very beautiful", and that people said Jefferson freed her because she was his daughter. Let’s go back to Madison Hemmings’ memoir written in 1873, and see what he had to say of his absconding older siblings: “Beverly left Monticello and went to Washington as a white man. He married a white woman in Maryland, and their only child, a daughter, was not known by the white folks to have any colored blood coursing in her veins. Beverly's wife's family were people in good circumstances. Harriet married a white man in good standing in Washington City, whose name I could give, but will not, for prudential reasons. She raised a family of children, and so far as I know they were never suspected of being tainted with African blood in the community where she lived or lives. I have not heard from her for ten years, and do not know whether she is dead or alive. She thought it to her interest, on going to Washington, to assume the role of a white woman, and by her dress and conduct as such I am not aware that her identity as Harriet Hemings of Monticello has ever been discovered.” Jefferson formally freed only two slaves while he was living: Sally Hemings’ older brothers Robert, who had to buy his freedom, and James, who was required to train his brother Peter for three years to get his freedom. Jefferson eventually (primarily posthumously, through his will) freed all of Sally's surviving children, Beverly, Harriet, Madison, and Eston, as they came of age. (Harriet was the only female slave Jefferson allowed to go free.) Of the hundreds of enslaved individuals he legally owned, Jefferson freed only these members tied to the Hemings family. Sally Hemings' children were seven-eighths European in ancestry genetic makeup, and three of the four entered white society after gaining their freedom. Their descendants likewise identified as white. Lastly, Jefferson’s will also petitioned the legislature to allow the freed Hemings family members to stay in the state of Virginia.  An interesting miniature portrait sold on eBay in 2012 which was said to be of Harriet Hemings. One of the papers inside the piece indicates the subject as "Harriett Hemings", president Thomas Jefferson had two daughter's with his slave Sally Hemings, named Harriett, one dying shortly after birth, and the other, often known as "Harriet II", was born at Monticello in 1801 and was known to be working in the textile factory by age 14. It was well known that she was very light skinned and could "pass for white". The interesting thing here that the artist truthfully portrayed was that although she had very light skin, she still had African American features. After Thomas Jefferson's death, although not formally manumitted, Sally Hemings was allowed, by Jefferson's daughter Martha, to live in Charlottesville as a free woman with her two sons until her death in 1835. The early Monticello Association however refused to allow Sally Hemings' descendants the right of burial at Monticello. So, the later life whereabouts of Harriet Hemings is quite a story and mystery unto itself. This woman appears to have vanished into thin air, or at least into Maryland as some sources contend at a time period in the late 1840s. Madison Hemings added knew the answer of her husband’s name, but declined to offer it up in public to protect her secret. He did give us a clue that he thought she possibly died between 1863-1873 because he hadn’t heard from her in ten years. Again, let me reiterate the fact that researchers, historians, authors and genealogists more talented than I have been searching high and low for Harriet Hemings for quite some time. It is great news to us that some of these folks have proposed that she disappeared to Frederick and is buried in Mount Olivet. I then ask the question: Why is this not a possibility? I remember moving to Frederick in 1974, and a popular bumper sticker that could be found here read: “Frederick, Maryland—Away from the Maddening Crowd.” I’m sure the sentiment was even more the case back around 1848. Harriet Heckman Instead of insisting that Harriet Heckman could be the former Harriet Hemings, I will take the approach of trying to find out who “our Harriet Heckman” was, based on the local records at hand, and exhaustive searches of newspapers, census records and family tree info. I also called on some of my colleagues for their expertise: Ron Pearcey, Marilyn Veek and Marcia Hahn. I've been trying to find anything pertaining to a family named Heckman, supposed in-laws of the Harriet we have lying in Area H. All I can go on here at the cemetery is that interment card that Ron completed with the names of the parents of Ann Sophia (Heckman) Kehne. On this it gave the name of Harriet Hemings and spouse George Heckman as I said earlier. Our interment book also proves that Mrs. Heckman is Mr. Kehne’s mother-in-law at the time of her death in 1870. Unfortunately, there is no George Heckman here in Mount Olivet. The same holds true for his name being absent in the burial records of Frederick’s Evangelical Lutheran Church. I’ve only run across this name of George Heckman as being married to Harriet Heckman in other books and online family trees stating a potential spouse for Harriet Hemings. Marcia Hahn, however came up with multiple references to a Frederick City Heckman family of the late 1700s and 1800s that connect to Harriet and Ann Sophia, but no records on a “George Heckman,” only a Johann George Heckman that died in 1787 at the age of one. I did find a G. Heckman as head of household in the 1810 US Census living here in Frederick County. He was between 16-25 and was co-habitating or married to a female of the same age range. This woman could not be either of our "Harriets" born in 1801, however. It is an interesting find, but one that needs more work. I think this fellow resided in northern Frederick County, and will revisit at end of this story. So outside of Harriet Heckman’s given birth date in our records of February 6th, 1801, I’m forced to start at Ms. Heckman’s true end of life (February 26th, 1870) and make my attempt to go backwards. This date is only slightly different than the May, 1801 date that the Monticello Foundation has in their records for Harriet Hemings’ birth, but it is pretty darn close, but I digress. Once again, on our interment card for Harriet, we don’t have parents listed for Harriet, but Ron had written in a spouse named Christopher Heckman, but not George. Marilyn Veek presented me with a copy of Harriet Heckman’s will dated March 3rd, 1870. Ann Sophia Kehne was her executor. It was nice to read Harriet’s own words and yes I did make note to look if she had indeed signed her last will and testament and not simply left a mark, like a majority women of her time period. A brief obituary appeared in the local paper at the time of her death reveals little about the woman. I did read that Ann Sophia was a loyal member of Frederick’s Evangelical Lutheran Church dating back to younger years. This got me thinking that if anything, Harriet Hemings would have been introduced to the Protestant-Episcopal religion at Monticello, but I think Thomas Jefferson was more philosophical than religious. My mind began suggesting that a smarter choice for a mixed-race individual, hoping to blend into white society, would be a person of German heritage, instead of one of English ancestry. Above all, this thought was grounded in the fact that slavery was less practiced by Germans here in earlier days, in favor of the family farm construct. The slave plantation was introduced by English and Scottish families. This holds true here in Maryland and our neighbors above and below. In addition, another ethnonym found in genealogy involves the notion of the “Black Dutch” of the early 19th century. These were dark-complected people of German, European or even Native-American descent. This would be a safer route compared to marrying into a high-brow, socialite with nosey family members asking you to prove your heritage for social standing purposes. Harriet Heckman appears in both the 1860 and 1850 US census records. She died shortly before the 1870 census was taken. In both records found, she is inferred to be widowed, while Maryland is given as her place of birth. She is also shown to have valued real estate in her name, a rarity for most people of this period. Examining the 1860 household, Ann Sophia can be found living with her mother, now being 24 years of age. It appears that the Heckmans have boarders, a family by the name of Weddle. The Williams’ Frederick Directory City Guide and Business Mirror of 1859-’60 lists Mrs. Harriet Heckman living on the northside of East 3rd Street between Middle Alley and Chapel Alley. Harriett bought this property, now 125-127 East Third Street, in 1854, and willed it to her daughter (Ann Sophia Kehne). Kehne sold it in 1897 (Note: the houses currently there today are estimated at 1900 and 1901 in tax records, so most likely not the ones in which Harriett and Ann lived). Unfortunately, I found next to nothing in the vintage newspapers I have at my disposal. However, it would make sense for a person wanting to keep a low profile to keep their head down. The 1850 census was my best opportunity to glean anything. It did not disappoint, but I did find that Harriet and Ann Sophia were living separately. Harriet is living with a woman named Margaret Lewis (age 40), formerly Margaret Ogle and widowed wife of an Isaac Lewis, a man born in 1808 in Washington DC, who died in Frederick in 1838. Step son of Michael Lambrecht. Mr. Lewis is buried in the Evangelical Lutheran Cemetery, however Margaret is buried in Mount Olivet. The couples’ two teenage boys, William and Charles, are living here as well. One more person can be found living here in 1850—65 year-old Sophia Gavier, or at least that is the way the name is transcribed by Ancestry.com. I would soon have a connection to the name Heckman when I learned that this was Sophia Gavier’s maiden name. More in a moment on that point. Meanwhile, Harriet’s daughter (and Ms. Gavier’s probable namesake), Ann Sophia Heckman, was living with the Harrison Conley family of Frederick. Harrison was a cooper and perhaps Ann Sophia (then 14) was helping with the family’s business, or was simply pawned off to because there was no more room at the Lewis residence. I am quite perplexed, but continue to think that the Harrisons could have been relatives of family friends, something I have not ascertained as of yet. Mrs. Conley was the former Rosanna E. Schell, perhaps a stronger candidate to have a familial connection to Ann Sophia and Harriet. One more person living here at this residence located on East Patrick Street, is Mary M.M. Schell (age 40). I have come up empty in trying to find any mention of Harriet Heckman in Frederick prior to this 1850 census. Unfortunately, Covid-19 has also restricted me from thoroughly researching local Frederick Town Herald newspapers of the 1830s and 1840s which I would love to do. My assumption is that Harriet is clearly widowed by 1850, and perhaps moved to Frederick from elsewhere upon her husband’s death. I have not been able to find either Harriet or George Heckman in the 1840 census as I had hoped to find either living in Frederick or perhaps Washington, DC with 5-year-old daughter Ann Sophia (born 1835). I assume the family lived elsewhere, because I have not found church records pertaining to Harriet’s marriage, Ann Sophia’s birth/baptism or George’s death. A proposed narrative would feature Harriet living in Washington (or elsewhere in Maryland) and meeting “a Mr. Heckman” (whether it be George or something else) in the early 1830s. The couple marries, and Ann Sophia is born in 1835. Mr. Heckman dies (sometime over the 15-year span (1835-1850). I saw two references in online trees that conjectured “George Heckman” dying in 1838 and another in 1848. Either way, this would precipitate a move, to Frederick, by the widowed Harriet in hopes to gain support of family or by the urging of family. Sophia Gavier, who was worthy of Harriet naming her daughter after, would be that key support system, especially due to the fact that her own husband (George Geweyer) died in 1826, just three years after her marriage. Jacob Engelbrecht spelled the couple’s last name “Geweyer” in his diary, so it’s still not certain as to the official spelling as it could be Geyer or Gaver, or any slight variation from this. As an aside, Sophia and George Gavier/Geweyer were married at Frederick’s Evangelical Lutheran Church, and thanks to Mr. Engelbrecht, we have a record of him being buried in the old graveyard behind the church. Another one of the challenges with this particular research project involves others buried in the Evangelical Lutheran Graveyard. Marcia Hahn informed me that there is a gap in the death/burial records as nothing was recorded from August 1807 through February, 1837. That’s a problem if the mysterious George Heckman died between 1835 and 1837, but anytime afterwards he would have been recorded if he died and was buried here in Frederick, and if he was a member of this church along with the rest of his family.  Heckman Family of Frederick As for a legitimate Frederick Heckman family, I found a definitive match, with the notable exception of a George as I mentioned earlier. They derive from a German immigrant named Christopher Heckman (1752-1828). Actually, this “Herr Heckman” did not come to Frederick by choice, but rather as a prisoner. He served as a mercenary, or Hessian, soldier during the American Revolution. He was captured at Yorktown, marched to Frederick, and imprisoned at the aptly named Hessian Barracks, today on the grounds of Maryland School for the Deaf. Upon his release in 1783, he, like many other Hessians, decided to stay in Frederick rather than return to Germany. He soon married Christina Davis January 24th, 1786 as both appear as members of Frederick’s Evangelical Lutheran Church. Baptismal records show a daughter, Christina, born later that year on November 26th, 1786. A son Johann George, mentioned earlier, was born to this couple on June 9th, 1788, but died on September 23rd, 1788 and is buried in the church graveyard. A second daughter Anna Catharina was born August 5th, 1789, but died just over two weeks later on August 22nd, 1789. She too was buried in Evangelical Lutheran’s graveyard. The historic church also has records for two other Heckman children: Johannes Casper and Maria Sophia. Johannes Casper was born September 18th, 1792. Like sister Christina, this is our only mention of him as he didn’t marry later in this church. No record of burial, but if his death occurred between 1807-1837, perhaps he could be resting in peace here without a stone. I want to put an asterisk next to this individual’s name as a possible “person of genealogical interest.” Could this be Harriet’s “George?” Maria Sophia Heckman has been previously introduced, and better known to us as Sophia (Heckman) Gavier/Geweyer. She was born May 17th, 1795. Her marriage was recorded as December 21st, 1823. She died sometime before 1860 and is most likely buried with her husband as she doesn’t appear in our Mount Olivet records. Surprisingly, Marcia couldn’t find her in the records of Evangelical Lutheran which is odd. Let’s briefly get back to family progenitor Christopher Heckman for a minute. His wife Christina died in 1810. He then married another woman, a widow named Catherine Ely who was a member of Frederick’s German Reformed congregation. No children were recorded as part of this union. Jacob Engelbrecht recorded Christopher Heckman’s death in his diary on September 16th, 1828: “Died last night or this morning in the 76th year of his age Mr. Christopher Heckman one of the Revolutionary soldiers who came to America from Germany in the Hessian Regiments. Buried on the Lutheran graveyard though he is a member of the German Reformed Church. His wife being buried there & his children being members of the Lutheran Church.” My colleague Marilyn Veek stumbled upon a few important tidbits, but unfortunately a will from Christopher Heckman was not one of them. She found two property deeds that indicated that Mr. Heckman had left property in his will, but could not find such document in Frederick County’s records. In one of these deeds, she found a very interesting sentence pertaining to property that would later be associated with Harriet Heckman. Apparently, Sophia Gavier/Geweyer inherited 1/4 of lot at 101 East Second Street (now 105 East Second) from Christopher Heckman. Sophia willed her interest to "my sister Harriet" in 1850. Harriet sold this property in 1854 (Note: the house currently at that address is estimated at 1880 in tax records), but this gesture (by Sophia) gives me overwhelming reason to view Harriet as a bonafide relative to Sophia. I do not think she meant “sister” in the biological sense, but rather in the vein of “sister-in-law.” Since Sophia makes this statement, I view Harriet as the daughter-in-law of Christopher Heckman, whether they ever met in real life or not. Harriet married Christopher’s son, perhaps after his death. However, all I can find through a viable search of church records is the existence of a Johannes Casper Heckman (b. 1792). It’s conceivable that he married Harriet, but what happened to him, and did he ever go by the name George? Or is the whole George name irrelevant? What’s in a Name? Well, I did find some other George Heckmans of the period in question who seemed remote possibilities. I found a will for a William Heckman of Frederick County whose executor in 1841 was his son named George Heckman of Franklin County, Pennsylvania. George sold William's property, located on the road from Emmitsburg to Frederick, in 1842. The man in question seems to have lived in the Emmitsburg area, just north of Mount St. Mary’s University. I saw a Frederick County Equity case from 1830 involving Troxalls (living a mile south of Emmitsburg) and it was stated that a George Heckman was currently renting a property. I found this George in the 1830 census and noticed he was living in close proximity to a few free Black residents residing in that area, which heightened my curiosity. My assistant Marilyn searched but did not find any deeds in which George Heckman bought real property. In1828, he sold livestock, farm tools and household goods. In 1832, he bought livestock, farm tools and household goods (from a different person) and in 1834 he sold to Felix B. Taney his grain crops from 90 acres "now in my possession". It seems, George was farming on his father's property. This rules out my theory of Harriet being married to this gentleman, while being a daughter-in-law to Christopher Heckman and sister-in-law to Sophia Heckman Gavier/Geweyer.  The United States Gazette (Jan 3, 1832) The United States Gazette (Jan 3, 1832) In the case of Harriet Hemings being Harriet Heckman, there is mentioned another possible Pennsylvania connection. Some think that Harriet Hemings' husband was a George Heckman, native of Philadelphia, and born in 1800. These sources state that the couple lived in Washington DC, Philadelphia, or both. They cite an individual named George M. Heckman whose burial site can be found on the popular Findagrave.com. This George Heckman is buried in Philadelphia's historic Laurel Hill Cemetery. His stone includes a death date of December 1849 but no discernible birth date. However, in Ancestry.com, I found a George M. Heckman born about 1787 and died September 11th, 1849, but no cemetery listed other than "a Philadelphia Cemetery." A little research on my part found that this man had the position as "a grain measurer" Philadelphia during his lifetime, a pretty good job. He was originally buried in Ronaldson’s Cemetery, which was obliterated in 1950, at which time bodies were reinterred in other cemeteries in the Philadelphia area. George’s stone reads that a daughter Mary Lee Heckman, who died before him, is also buried with him. In researching further, it didn’t seem as if this man had Maryland roots, or any connection to Christopher Heckman. His family members were from the greater Philadelphia area and New Jersey. I found news of this horrific accident which occurred in Pennsylvania in papers all over in 1843. You have a man named George Heckman dying of injuries sustained. I haven't been able to make a connection to a family based on the nature of a railroad locomotive operator's nomadic nature. I wouldn't think this would be our George, as it also seems to call for a home residence in eastern Pennsylvania. You never know, though. Back to that story of Harriet Hemings. She went to Washington, DC aboard a stagecoach in1823 and is said to have married George Heckman and began raising a family as she had passed into white society as a free woman. It’s been said that this woman apparently fell off the face of the Earth in the late 1840s. Later in life, her brother stated that she lived out her life in Maryland, but no sign of where. She likely died around 1870, the time of Madison Hemings’ memoirs. Hmmmmmm. The Monticello Society has done research and are obviously aware of the potential Kehne connection but have discounted this on grounds of not having DNA evidence. In accordance with the US Presidents Project, the relationship of President Jefferson to George Heckman, Anna Sophia (Heckman) Kehne and Mount Olivet have been disconnected by a leading genealogist at Wiki Tree. Oh Johann Casper Heckman, what ever became of you, my friend? Looks like I may have to bring Henry Louis Gates, Jr. into the fold as my next step. Thanks for sticking with me on this unfinished odyssey. To be continued..... Note: Special thanks to Susan Reeder Jesse for sharing this story with the author.

10 Comments

Bonnie Kobielak

8/18/2021 05:33:25 pm

Absolutely Amazing! Can’t wait to learn more!

Reply

Ashley

5/17/2022 08:53:28 pm

The miniature portrait of Harriet Hemings has a very similar nose as Thomas Jefferson, also this was a very interesting read and I can't wait for more info because I'm very interested in finding out more about Harriet and her mother Sally Hemings.

Reply

Misty

5/27/2022 10:46:52 pm

Very interesting read. I am looking forward to updates on this article.

Reply

Tasha

8/15/2022 07:18:15 pm

Fascinating story—best of luck in your continued research! I can’t wait to hear more!

Reply

Jamie Bronstein

6/5/2023 06:01:01 pm

"Harrison Conley" = Beverly Hemings.

Reply

Leslie

7/12/2023 12:45:20 am

I couldn't find anything on a Harrison Conley. Where'd you get that info? If you don't mind me asking.

Reply

KC

7/19/2023 09:44:23 pm

Lot of research went into this! Has anyone traced this Anna Sophia (Heckman) Kehne to any modern day descendants she may have to see if they could donate DNA to test the claim that they are related to the Jefferson family?

Reply

Faith

3/10/2024 12:07:12 pm

Great research on Harriet Hemings! Any recent found or updates?

Reply

JOHN FROIO

5/8/2024 09:46:47 pm

Very interesting article. Would love to read about any further development of this story.

Reply

Alexandra rosina

5/12/2024 01:27:09 pm

Il nome di harriett può essere modificato in henriette e il cognome petit ed era sposata con jacob

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed