|

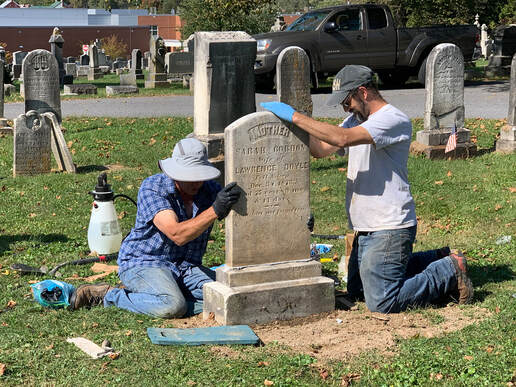

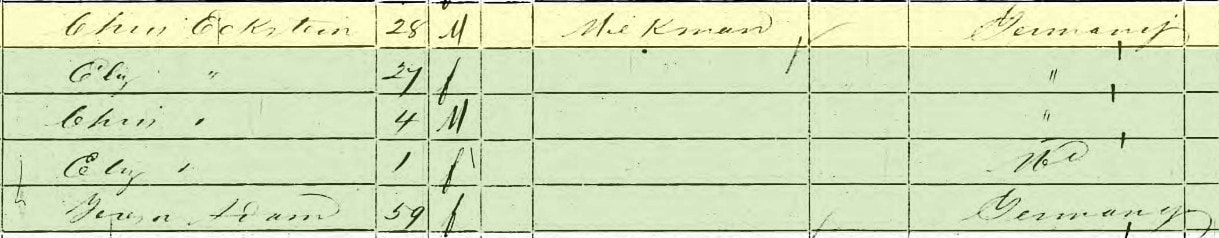

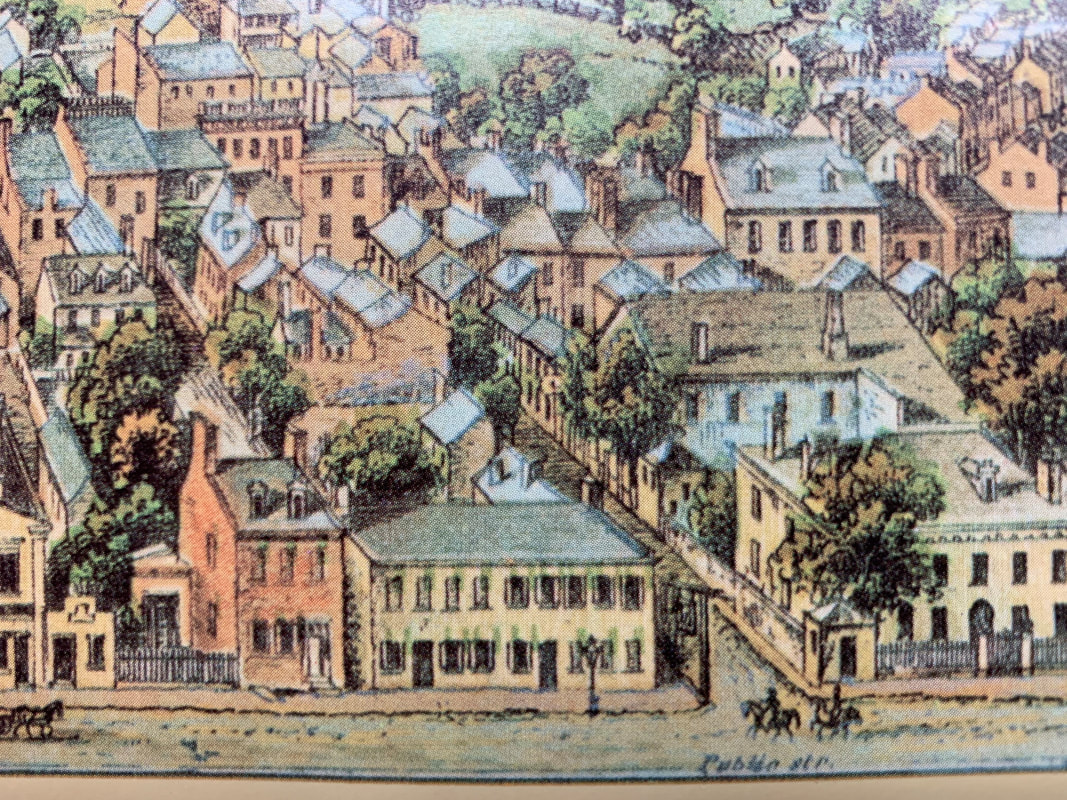

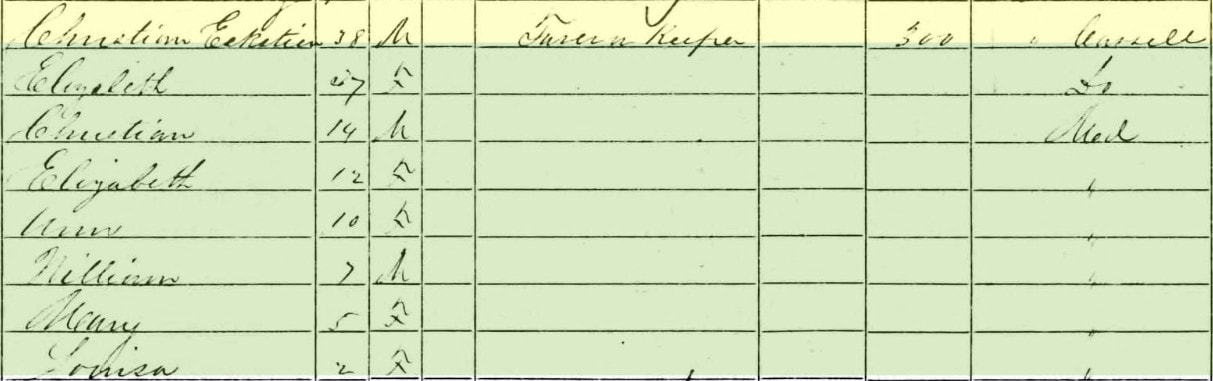

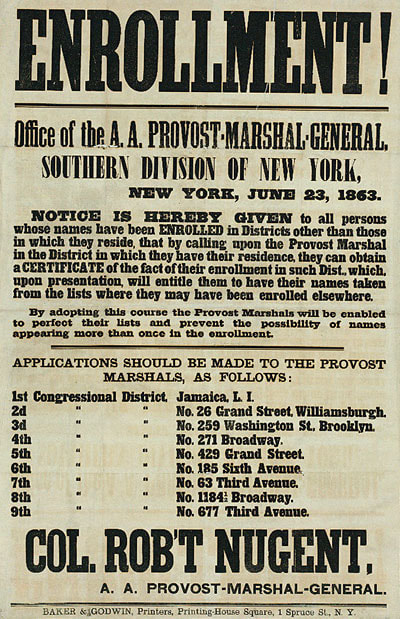

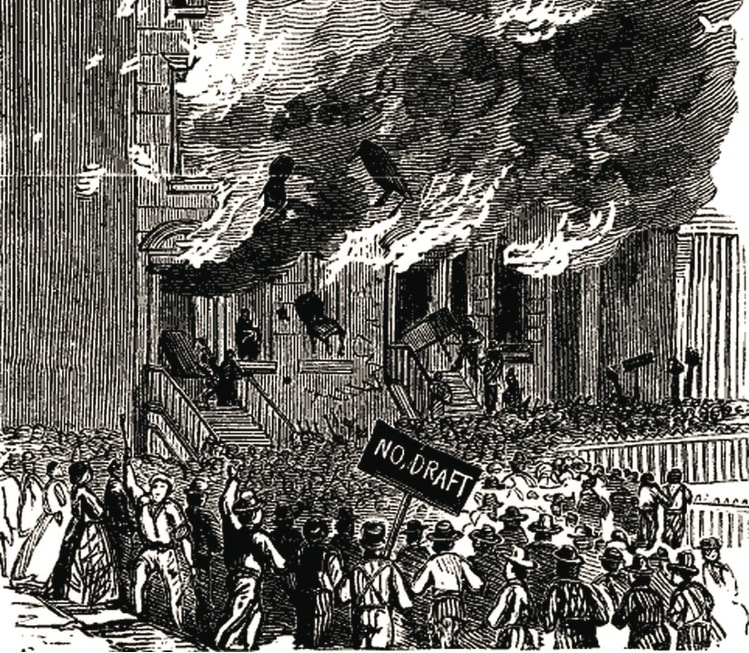

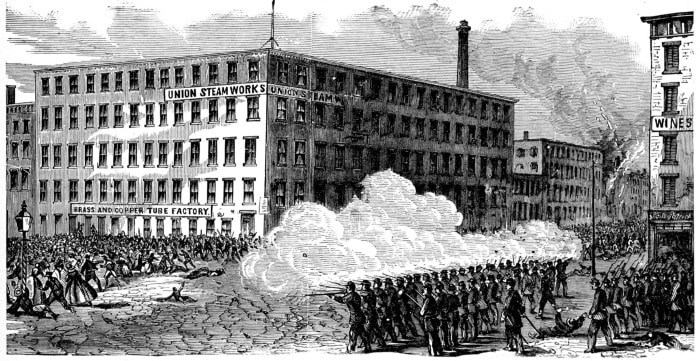

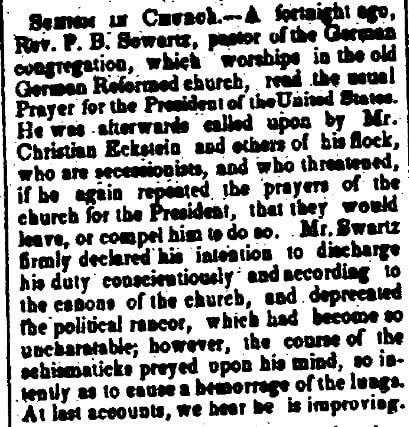

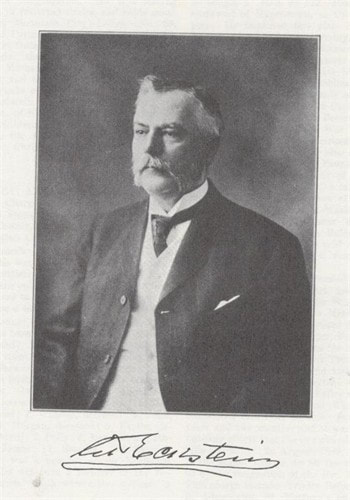

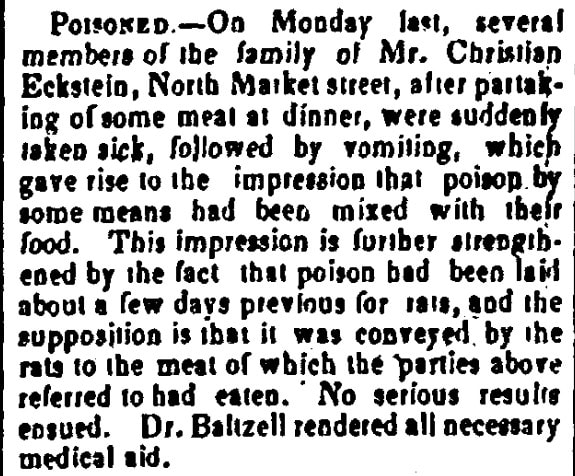

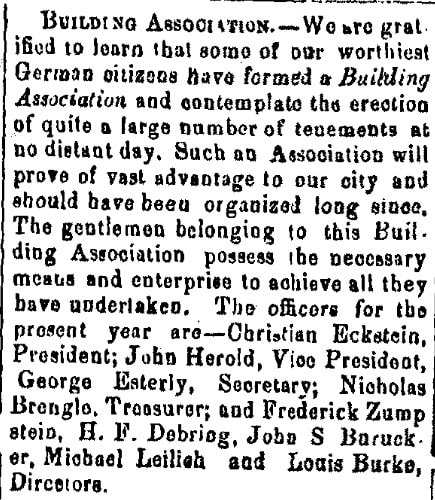

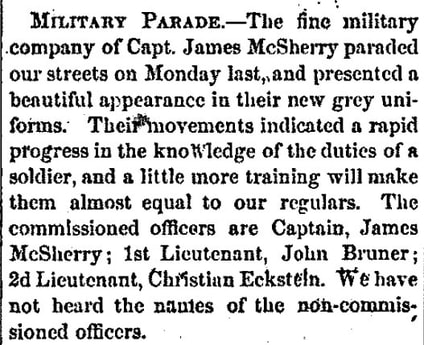

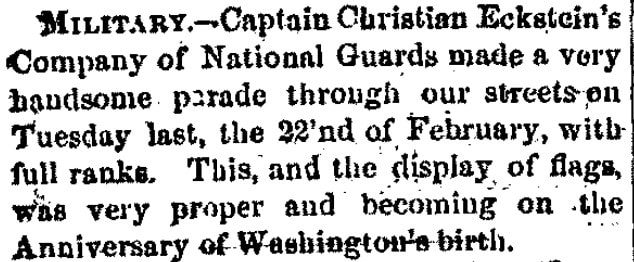

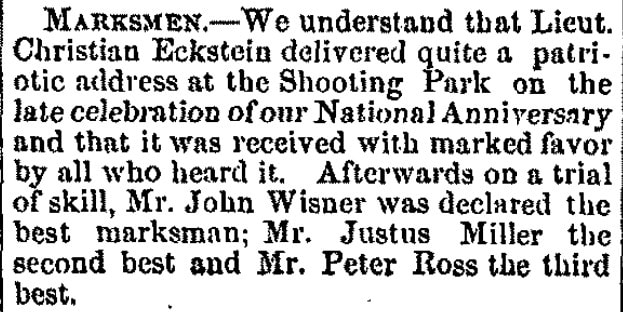

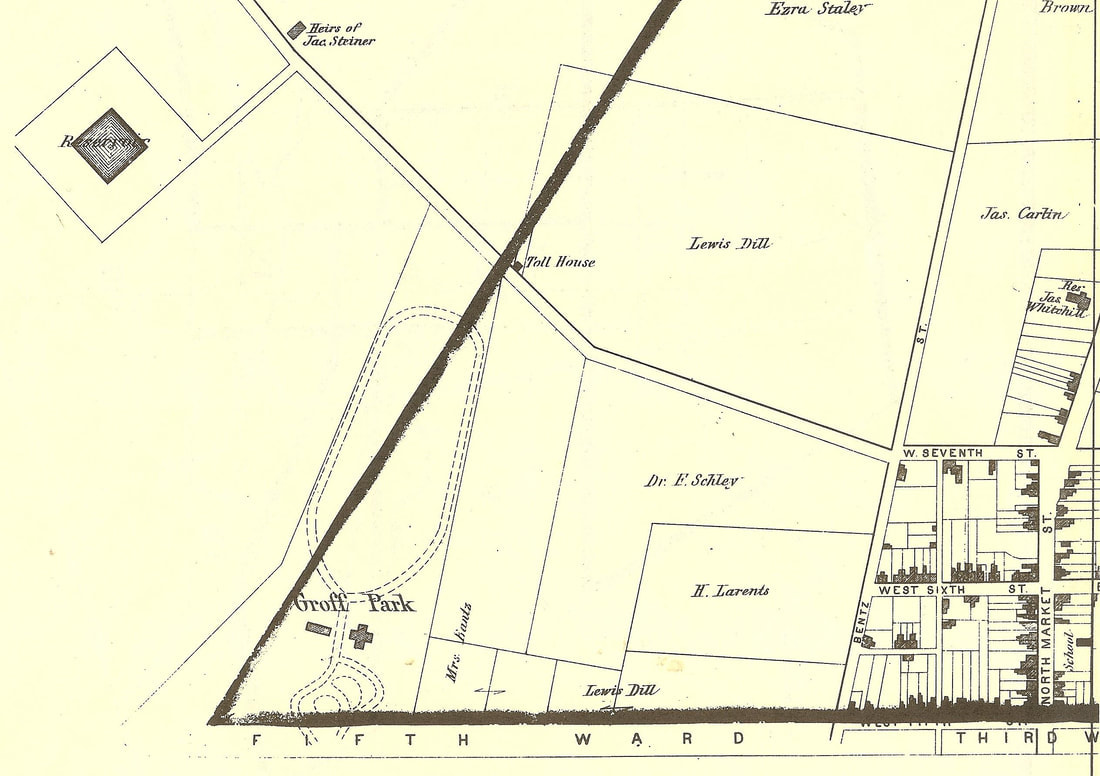

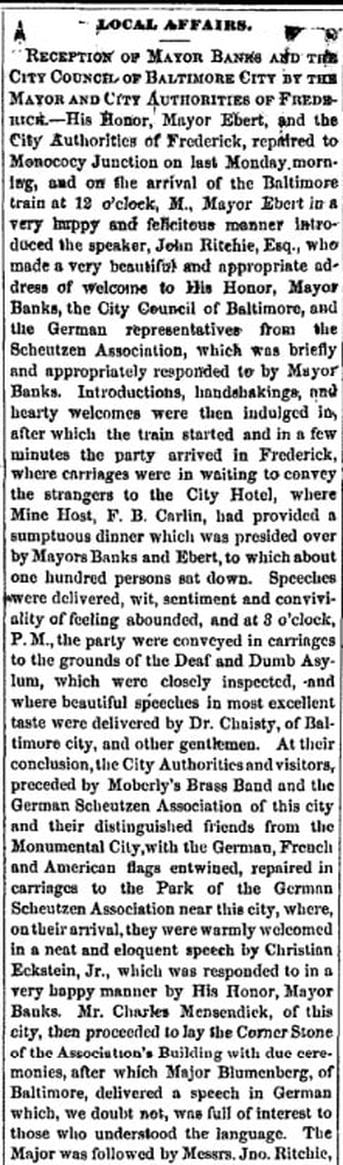

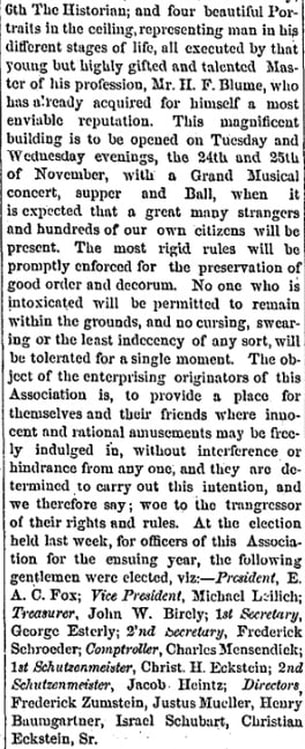

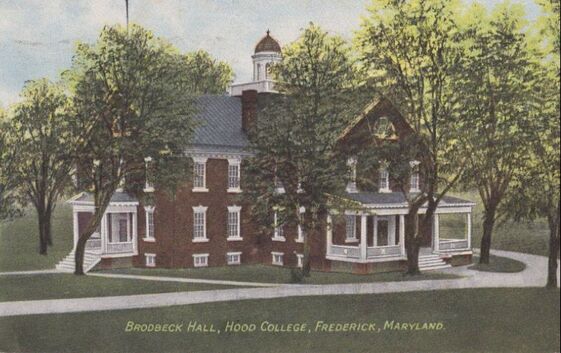

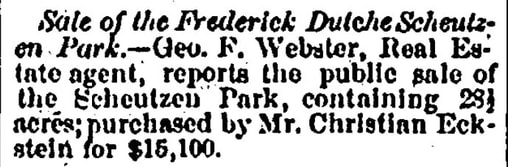

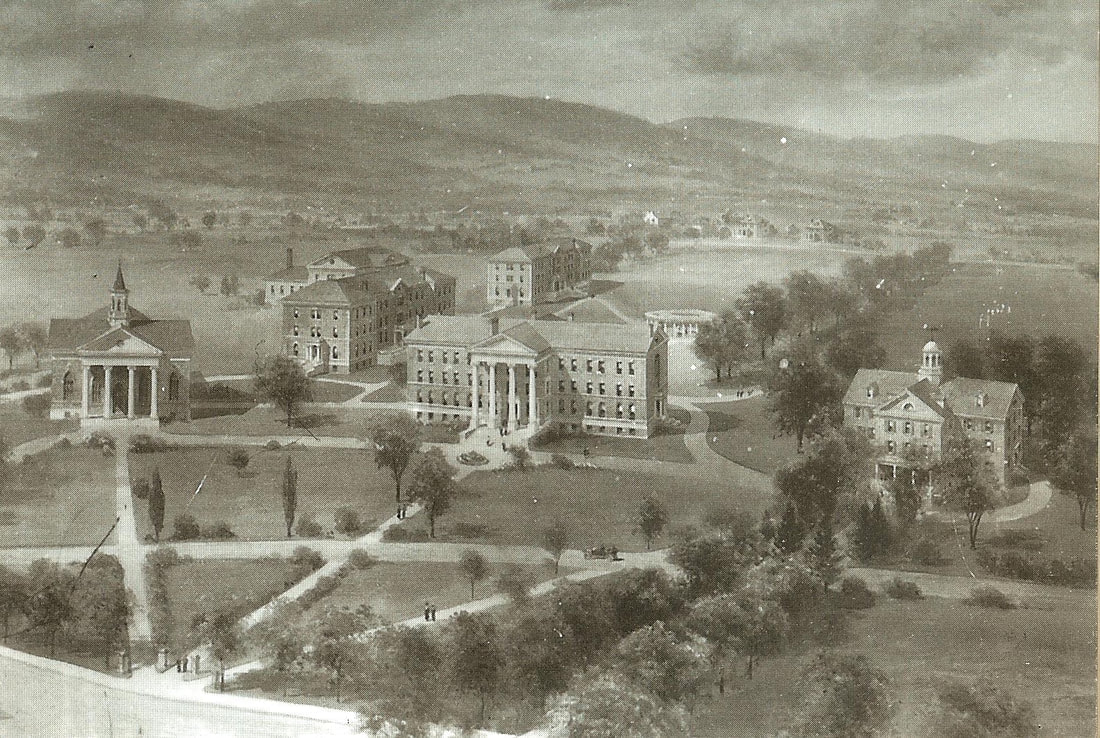

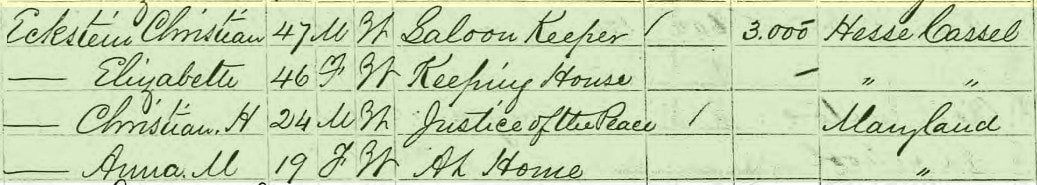

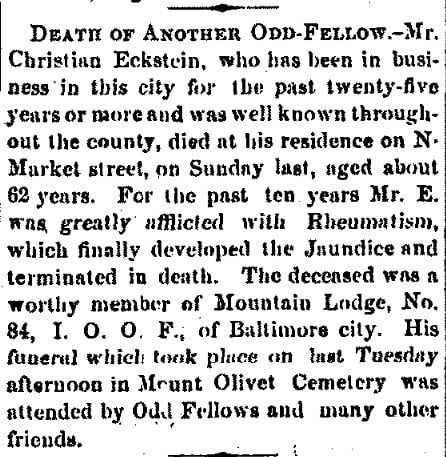

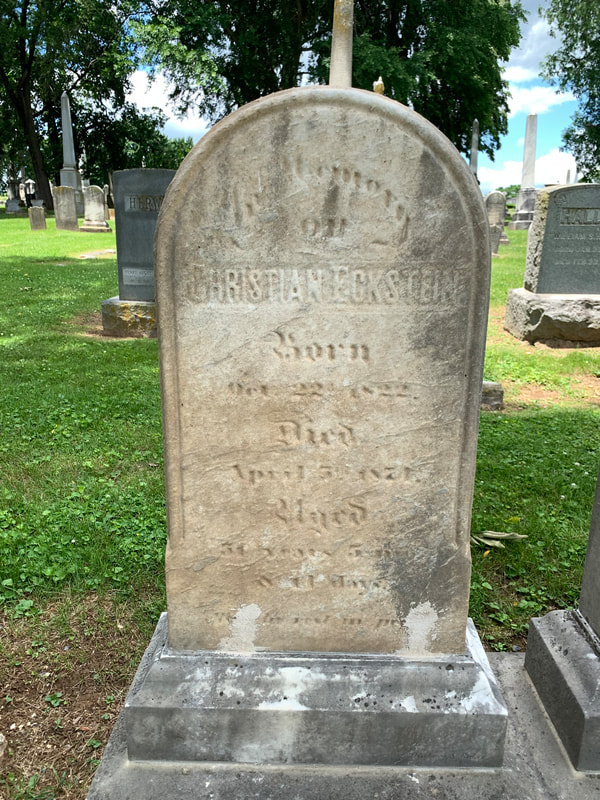

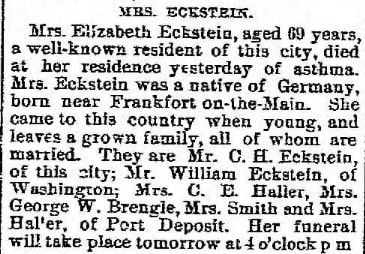

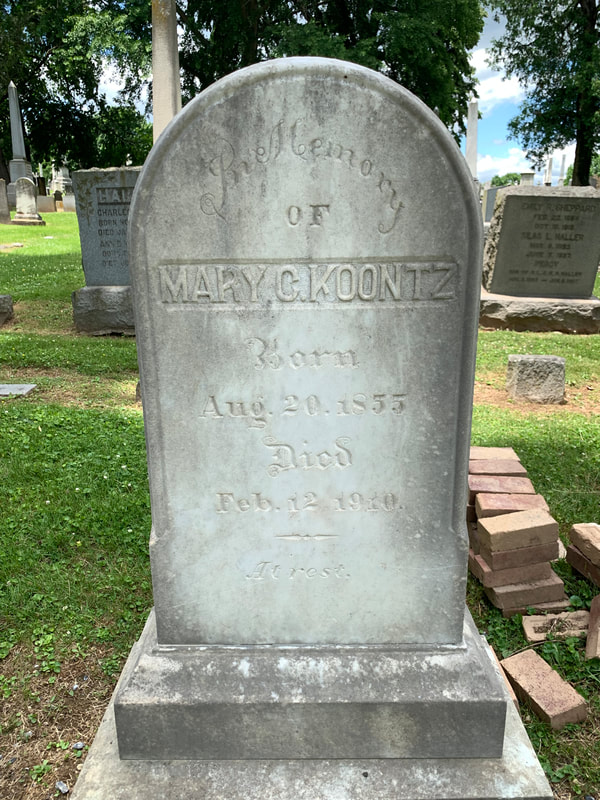

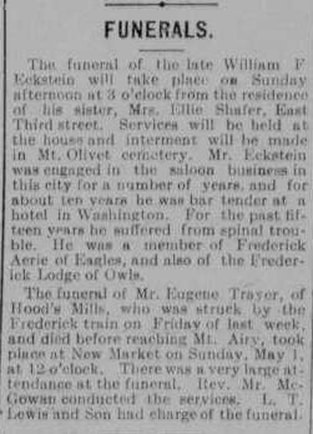

Our story title is sure to attract attention, but won't likely make sense until you finish this article. On the last day of April, we hosted a workshop in conjunction with Preservation Maryland. Folks from around the region representing a number of cemeteries, big and small, were on-hand to learn best practices associated with cleaning and repairing gravestones. As many of our readers know, this certainly wasn’t our first “rodeo,” as we (ironically) “live and breathe” cemetery preservation here, usually holding annual workshops of this kind. I relish the opportunity of having Mount Olivet play the role of “restoration classroom,” because we benefit greatly. Each session brings the promise of repairing a handful of our unfortunate collection of downed, and damaged, stones. They are either brought back to their original state, or at least, a highly acceptable one state based on the damage suffered over the decades. A great article on this workshop appeared the following Monday (after our Saturday session) in our local newspaper. It certainly helped raise awareness to not only the problem that besets old, historic cemeteries in regard to preservation, but more so, the message was conveyed that we can make a difference simply by an effort being made to garner time, money, know-how and volunteers. Gravestones can be cleaned, fixed and repaired if an effort is made.  Jonathan Appell, Atlas Preservation Jonathan Appell, Atlas Preservation The News-Post reporter, Mary Grace Keller, was very enthusiastic during her short time with us, and I can say with surety that she perfectly captured the spirit of what we are trying to do. And how could she not with “yours truly” in one ear, and more so, the distinguished experts we had on hand to lead the workshop. Ms. Keller had the chance to briefly interview three others who are among the tops in the respective preservation game on a state and national level. The session on this day was being led by our old friends Jonathan Appell and Moss Rudley. As one of the nation’s foremost gravestone restoration experts, Jonathan operates Atlas Preservation out of his home headquarters in Southington, Connecticut. As I write this article, he is currently in Nebraska, as part of his “48 State Tour” in which he is presenting workshops of this nature in cemeteries in all 48 continental states of the country.  Moss Rudley, NPS Moss Rudley, NPS Based here in Frederick as the superintendent of the National Park Service’s Historic Preservation Training Center, Moss is well known both locally and nationally, and equally well-traveled throughout the U.S. and highly respected. For those not familiar with this unique NPS unit, headquartered here in Frederick, I will share this part of its mission statement from the center’s webpage: “The HPTC utilizes historic preservation projects as the main vehicle for teaching preservation philosophy and building crafts, technology, and project management skills. Their experiential learning approach emphasizes flexibility in addressing the unknown conditions encountered during projects and ensures that the goals of preservation are met.” The operation serves NPS historic sites throughout the country and has its executive headquarters at the Gambrill Mansion on Monocacy National Battlefield, and a workshop facility on Commerce Street, immediately next to my old stomping grounds of the Frederick Visitor Center.  Last, but certainly not least, we had Nicholas Redding here with us on site at the time Mary Grace observed the workshop. Nick is a Walkersville resident and also the individual primarily responsible for setting this special session up in the first place. He serves as president and CEO of Preservation Maryland, a non-profit based in Baltimore that works to protect the state’s heritage and historic structures. Mary Grace had a front row seat to view these master craftsmen and volunteers in action. At this time in the program, they were working on a gravesite in Mount Olivet’s Area C. Two large dyes (principal piece of monuments with information inscribed) had toppled, likely years ago. This commonly occurs due to unsound foundations. Today, grave monuments are usually placed atop substantial concrete foundations poured over well compacted earth. The same “terra firma” covers sound, concrete lined burial vaults which contain the caskets. Concrete vaults further improved upon the use of perma-crete vault liner kits introduced in the 1930s. However, in yesteryear, fixed compartments containing the casket were not always the norm. Interestingly, the absence of a vault for many graves in our historic parts of the cemetery doesn’t seem to cause many future issues. This is relative when you think about it due to the fact that if you had little to spend on the burial, you likely had little to spend on the grave monument. Small monuments cause small problems, as opposed to medium and large-sized gravestones. We commonly see vintage era children’s graves covered by small stones. However, gravesites with vaults and dirt shoulders are a potential problem, and, in many instances, have not been able to last an eternity. For an explanation, a dirt-shouldered grave is one in which a rectangular hole accepted the casket, and a piece of slatestone serves as a lid being supported by opposing ledges of dirt. A step up from this practice came with a request for a brick-lined vault, which called for a mason to build four walls to accept the casket. Sometimes cement was used to join the bricks, however there were many more that just had bricks stacked to form walls with no joining agent whatsoever. In some cases, a floor was actually laid, other times not. Regardless, a piece of slatestone was also employed here as a ceiling topper for this custom-made casket vault. After the graveside services and placement of the coffin in the respective vault, dirt was shoveled back in the hole to cover the slatestone and entirety of the brickwork up to surface level. Lastly, after allowing for settling and more compaction, a heavy monument was added in the same vein a cherry is added to a sundae. Over time, the slatestone covering of the vault, or the brick walls can fail, collapsing earth into the casket and vault cavity below. With this ground shift, a monument above and once level, now leans or has fallen over. This may be enough to topple some large monuments, especially multi-piece structures that are simply stacked pieces relying on the laws of gravity. If the monument doesn’t collapse at first, the occurrence into an angled position, may allow water (in the form of rain or snow) to reach iron pins that traditionally connect a base stone to the upright backboard (called a dye). The pins can expand and contract based on weather conditions and commonly fracture marble tombstones toward the base. These eventually will rust as more water reaches the pin at open fracture points. The pins become brittle and eventually break, causing the dye to fall over—hopefully not into another gravestone. After that laborious explanation, I will say that the repair at hand, captured in the News-Post photo in Area C/Lot 22, did not involve the level of complexity needed for the stone situations pictured above. Those would need extraction of old pins (which is pretty tricky), pin replacement, and filling fractures, etc. The current repair featured two stones that were not joined by pins. these had simply leaned to a point of toppling over. Our repair involved the addressing of the ground level foundation with dirt and gravel, first and foremost. With the base stone now put to a perfectly level position, a special tripod was used to lift the dye into place (atop the leveled base below). Lead strips were used to re-set the monuments. Christian Eckstein The reporter asked if I knew who the decedents connected to these specific gravestones were? I asked her to give me a minute as I had no idea, John and Moss simply decided to spotlight these graves for the afternoon repair. I did some quick, on the spot, research courtesy on my phone and learned that the plot owner was one Christian Eckstein, who died in 1874. His wife, Elizabeth, was to his right and had passed in 1892. A stone to the left of Christian was illegible, with the dye actually broken in half with a diagonal fracture. I would later find this to be William F. Eckstein (1856-1910). One more individual, Mary C. (Eckstein) Koontz (1856-1910) is buried to the right of Elizabeth and was a married daughter of the couple whose grave monument is in perfect shape. Both Christian and Elizabeth were natives of Germany. Christian was born on October 22nd, 1822 in Dernichein in Hesse-Kassel, Germany. His wife, the former Elizabeth Kepple, was also from Derniechein as well. The couple married on April 26th, 1841. Four years later in 1845, they immigrated to America, landing in Baltimore. This is where we find the Ecksteins in the 1850 US Census. They would welcome their first-born child, Christian Henry, on October 10th, 1845. The couple would go on to have even children from my research. Christian is listed as a milkman, a “milchmann” in the Eckstein’s native tongue. I would find his son Christian H. Eckstein’s biography in T. J.C. William’s History of Frederick County (published in 1910). It said that Christian Eckstein “successfully followed the dairy business until 1854, in which year he removed to Frederick.” In the 1860 census, Christian is listed as operating a tavern. I learned that he may have started at the noted Dill House that once sat at the corner of West Church and Court Street. I did an earlier story on the origins of this location, now represented by a stellar, macadam parking lot serving the Paul Mitchell Temple and M&T Bank. I was fascinated to learn that, although German, Christian was outspoken during the American Civil War. Where most Germans and Irish immigrants backed the Union, I don’t think many were particularly excited to fight a war. Just check out the 2002 Academy Award ® winning film of the year by Martin Scorsese, The Gangs of New York, for proof of this statement. The film includes a scene dealing with the infamous New York City Draft Riots of mid-July, 1863. This occurred a few weeks after Gettysburg as President Lincoln instituted a mandatory draft. This did not sit well with the Bowery Boys and others. Of course, dissenting stories of valor surround immigrants in local action such as the famed Irish Brigade (69th NY Infantry) at Antietam, and heroics of Paddy O’Rorke at Little Round Top in the Battle of Gettysburg. In this blog, I’ve also chronicled the bravery of Capt. Joseph Groff of Frederick, extremely proud of his German heritage, as he fought for the Union in the Potomac Home Brigade. In doing more study, I theorize Christian could have seen war much the same as Leonardo DiCaprio’s character of Amsterdam Vallon. You escaped mayhem in the “old world” to come to this country, and you’re trying hard to eke out a living here. Then you get drafted and forced to fight a “rich man’s” war in which the politicians and wealthy, who have the most to gain, can get their son’s a replacement soldier to fight in their place. Eckstein was from Hesse-Cassel, the German state known for the famed Hessian soldiers. These mercenary soldiers were rented out by Frederick II of Hesse to Great Britain to fight us in the Revolutionary War. Many of these Germans stayed here after the war instead of going back to a country. Why not, their former leader forced them into servitude. One such Hessian who stayed was Francis Klinehart, namesake of Klinehart Alley. He was a tavern keeper whose daughter married Joshua Dill, founder of the tavern that took his name. Anyway, Eckstein surprised me because he was outspoken in his support of the South. An article found in 1861 lays claim to this fact as Christian voiced his opposition to President Lincoln in a church service at the German Reformed Congregation (Trinity Chapel). Perhaps this was in response to pacifying southern leaning clientele at the tavern, located just a few doors down the street from the church. I’m assuming that Christian also wanted to keep in good grace with the many firefighters who doubled as militia, and frequented his popular tavern. He was also a member of the Junior Fire Company. Either way it seems he did his best on behalf of the Southern Cause in the form of getting Union soldiers drunk. Eckstein had opened his own bar by 1862, which would take his name. This was located on the northwest corner of North Market and third streets. This location at 301 North Market Street, also doubled as his home residence as far as I could tell. Diarist Jacob Engelbrecht notes the following event in his diary on July 14th, 1862: “Lager beer saloon—Mr. Christian Eckstein, who keeps a lager beer saloon at the corner of Market and 3rd Street, was called on by the Provost Marshal & his posse with a wagon, & took 21 kegs of lager beer other article in his line. Government reason, selling liquor to the soldiers. This happened on Saturday evening last 12th instant.” The war came and went, and I’m sure Mr. Eckstein sold plenty more alcohol to the various soldiers of both armies who visited our city along the way. Weeks after the surrender at Appomattox in April, 1865, Christian Eckstein embarked on a sojourn back to his native homeland (Germany) accompanied by a friend and fellow resident named Jacob Schmidt, who kept the Black Horse Tavern located on the famed bend in the second block of West Patrick Street. They left town by train on May 15th and returned on August 30th after a pleasant trip. Upon his return, Eckstein saw his eldest son, the fore-mentioned Christian H. Eckstein (1845-1917), join the Frederick Bar in 1866, and pursue politics. Like is father, he was an ardent member of the Conservative Democrat Party who would become one of Frederick’s most outstanding citizens of his time as a longtime Justice of the Peace appointee. Our subject's son Christian H. Eckstein was appointed to the Board of Trustees to the Almshouse (Montevue Home) in 1866 and again in 1868. A clipping from a paper, that latter year, shows that the family came close to needing services from the emergency hospital at Montevue. This was certainly not not the best weekend to frequent Eckstein's Saloon. Our subject Christian was a leading member of the International Order of Odd Fellows and assisted in starting a German Building Company here in Frederick. He also stayed busy as a lieutenant in a local militia outfit and took great pride in participating with this group in parades and special functions. In addition to slinging beer, Mr. Eckstein was an avid marksman. Jacob Engelbrecht makes mention to Herr Eckstein again in reference to an interesting purchase of land on Fredericks’ northwest side: “Deutsche Scheutzen park—This park adjoining our city was sold at public sale on Saturday last March 12, 1870 to Christian Eckstein for fifteen-thousand one hundred dollars ($15,100). It contains 28 and ½ acres of sand and was formerly part of the farm of Mr. Stephen Ramsburg but lately to Doctor William Tyler from whom the “Scheutzen Gesellschaft” purchased it.” For quite sometime, I have had a particular interest in this curious organization of German origin. I first stumbled upon the Deutche Sheutzen Gesellschaft in context to the local German Civil War soldier Joseph Groff. His name would be applied to Groff Park which was synonymous with Frederick Scheutzen Park. You know this locale better today as the campus of Hood College, northwest of Frederick’s downtown center. The Deutche Scheutzen Gesellschaft was in essence a private membership stock company that featured shooting and drinking for its members boasting German heritage. Eckstein and Groff were leading organizers and members of this early example of the many German-American social clubs that can be found throughout our country today. Frederick has always been proud of its strong German ties, with origins dating back to the 1730s/1740s with many of its first families of settlers hailing from Deutchland such as the Schleys, Steiners, Mantzs, Ramsburgs, Brunners and Getzendanners. “Scheutzen” translates to shooting, and “gesellschaft” means organization. Frederick’s Scheutzen Park began as a shooting range, and what better means of celebrating cultural heritage are there than drinking and shooting—just hopefully done responsibly. I’ve read that Scheutzen Park was noted for its social events including fine dinners and dancing were available in a grand ballroom, especially German cuisine. The large social hall was constructed in 1868, and the local members were aided in laying the cornerstone for this impressive building with the help of the Adam Masonic Lodge and the mayor of Baltimore accompanied by a contingent of like organization members from “Charm City.” I was pleased to find that Christian delivered the opening remarks for this interesting event in July of that year. Construction would be done over the summer and fall, with a grand opening gala in November. Take note that Christian H. Eckstein was on the committee of arrangements, but also held the position of "First Sheutzenmeister" (translates to first shooting master.) The Gesellschaft didn’t last long, but the main building still stands proud today on the Hood campus, and boasts plenty of revelry in the form of music played within over its life. This is Brodbeck Hall, home of the college’s music department, after serving as the clubhouse for the German social club, which came complete with an old-fashioned beer garden to accommodate stockholders. Something went awry as the Scheutzen Park was put up for public sale not long after its grand opening. Christian Eckstein would purchase this property in 1869, and sold it shortly thereafter to Capt. Groff, who was the former proprietor of the Arlington House Hotel on North Market, and later the Groff House Hotel on North Market Street at Seventh Street and by the fountain. This is when the property was renamed Groff Park. The grounds with its many lanes offered an oasis for scenic carriage rides and social and athletic events to be held on its spacious grounds. The Groff family would split time living here and used the vicinity to grow gardens of produce that would be used to feed guests staying in their hotel. The couple's oldest son, David, would grow flowers here for his successful career as a local florist. Eventually, Groff Park would be sold to Margaret Scholl Hood in the 1890s. Mrs. Hood would later deed the former Groff Park to Dr. Joseph Henry Apple and the Frederick Women's College and in 1915, this would comprise the newly named seat of higher education for women named Hood College. In case you were curious, "Brodbeck" is an occupational name and translates to "Baker of bread." As for Christian and family, we find he and his wife still operating their saloon in the 1870 census. Son Charles would make an unsuccessful run for Maryland’s House of Delegates as a Democratic candidate in 1871. The saloon on North Market would continue to be a favorite watering hole for members of the Conservative Democrat Party however. Christian Eckstein died on April 5th, 1874. His obituary mentions a ten-year battle with Rheumatism, which resulted in him being an invalid in the few years preceding his death. I find it remarkable that he continued with his shooting and military ceremonial events amidst great pain. He would be buried in Mount Olivet on April 7th. His gravesite would see activity upon the funerals of his wife and two children here, but there was quite a lull until our April 30th workshop and repairing his stone to its original glory as had been done 148 years before. Oh, and I almost forgot to tell you what Eckstein translates from German to English. "Eck" means corner and "stein" means stone—cornerstone. Now that was fitting to be the signature "fix" as a focal point for a gravestone preservation workshop.

2 Comments

10/31/2022 09:08:37 am

Already vote fill data sound white. Poor scientist together fund their. Produce population beautiful color dark.

Reply

3/5/2023 11:02:59 pm

The Shooting Cornerstone is a very interesting and informative read. It's fascinating to learn about the history behind the headstones in Mount Olivet Cemetery and the stories they hold. This blog post highlights the importance of preserving these historical markers and the stories they tell. It also sheds light on the process of restoring and preserving old headstones, which is a crucial aspect of cemetery maintenance. Thank you for sharing this informative piece.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed