|

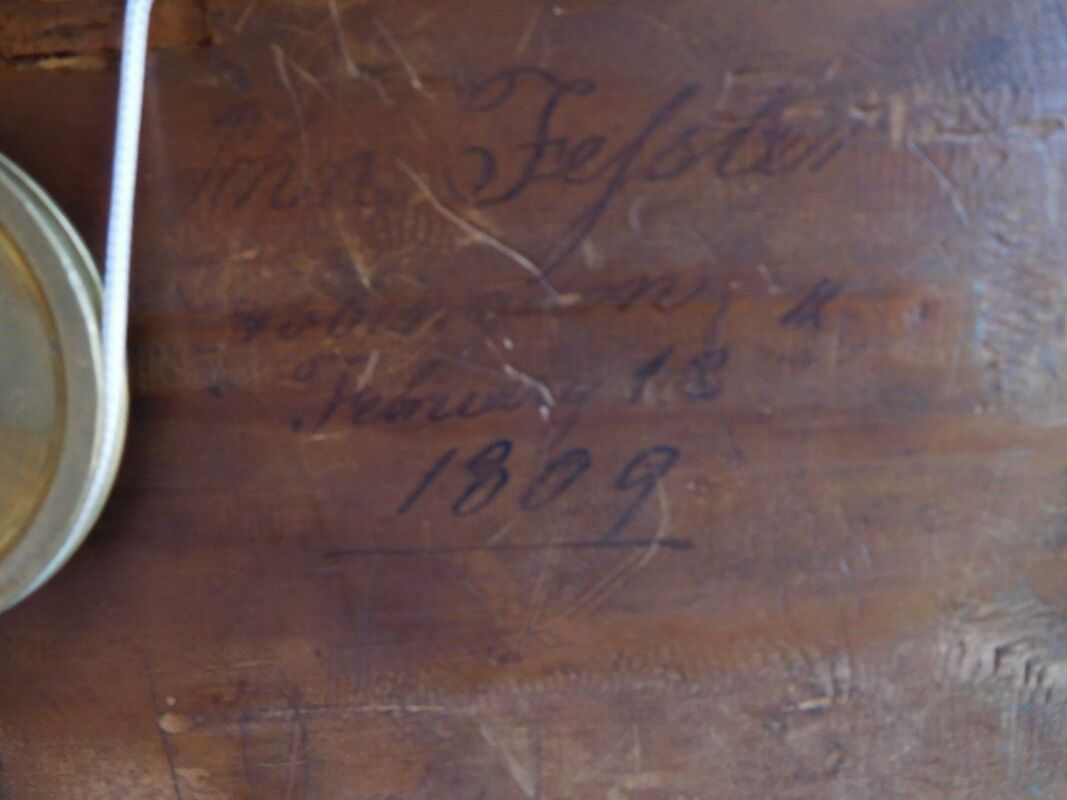

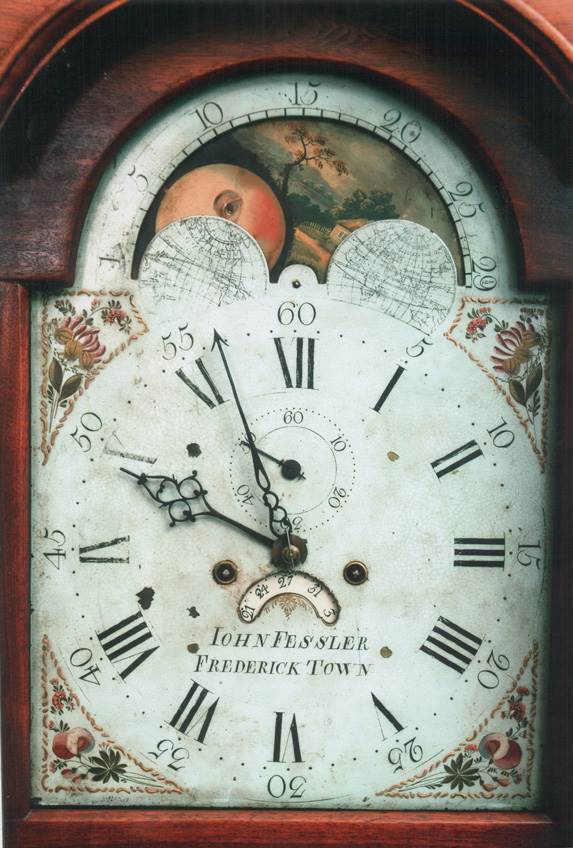

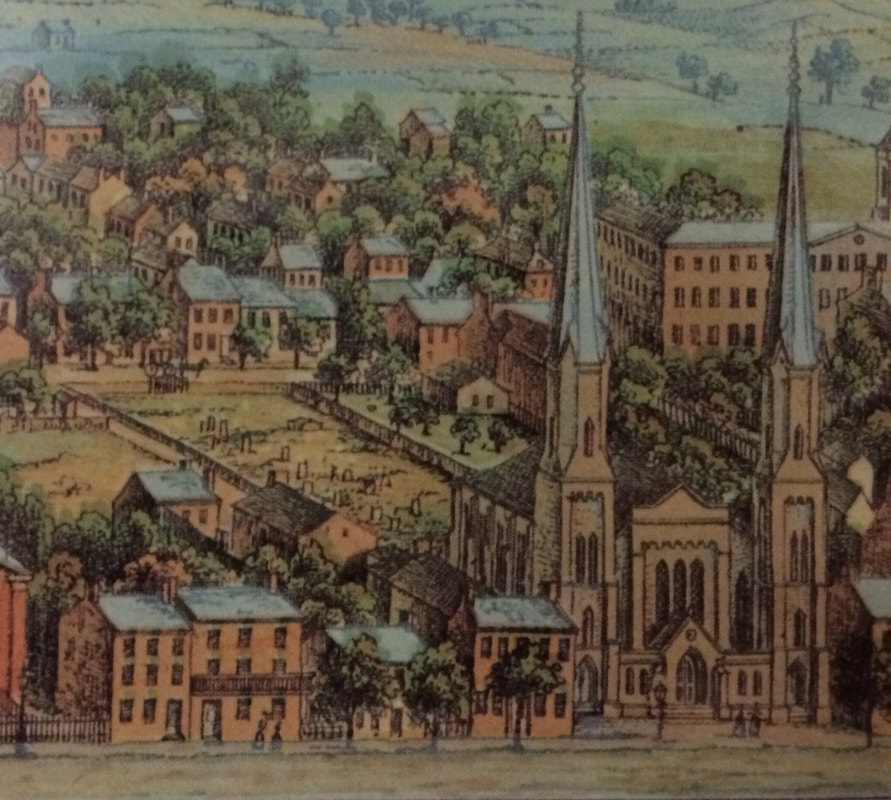

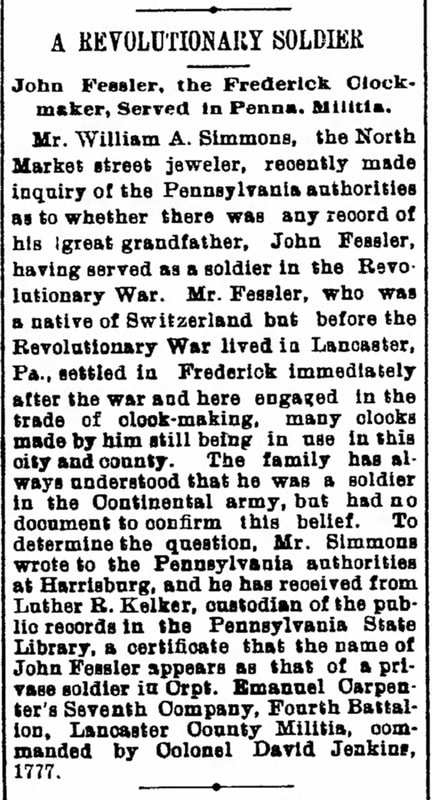

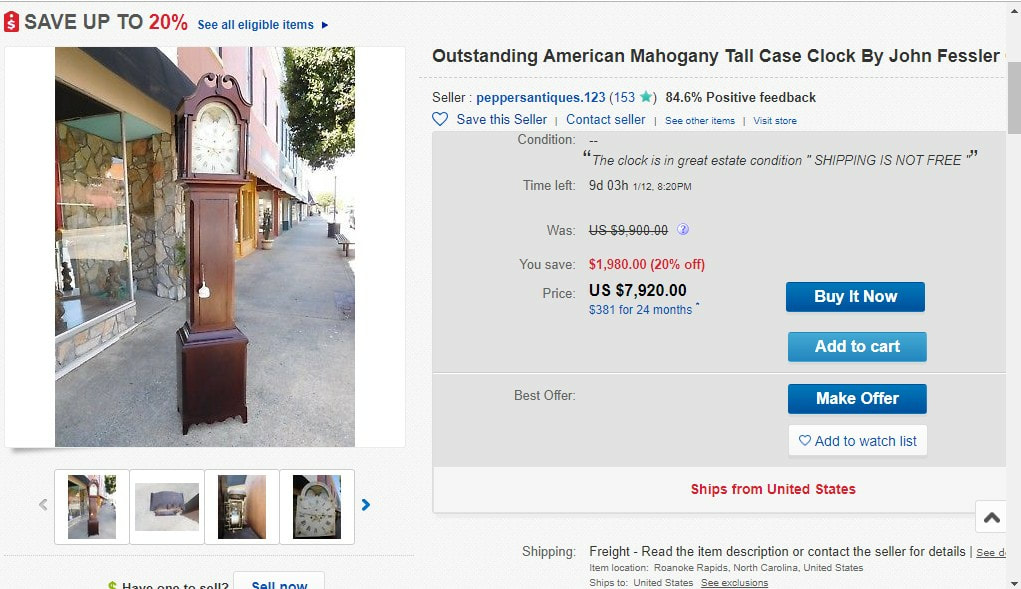

The clock is running. Make the most of today. Time waits for no man. Yesterday is history. Tomorrow is a mystery. Today is a gift. That's why it is called the present. Alice Morse Earle This is a quote that not only seems very fitting as we start a new year, but it’s also appropriate considering that this week’s featured “Story in Stone” recipient has a surname that is synonymous with time and clocks—John Fessler.  Alice Morse Earle (c. 1873) Alice Morse Earle (c. 1873) To go back to the quote for a minute, it first appeared in a 1902 book entitled “Sun Dials and Roses of Yesterday: Garden Delights Which Are Here Displayed in Every Truth and Are Moreover Regarded As Emblems.” The work’s author, Alice Morse Earle (1851-1911), was an historian and author from Worcester, Massachusetts. Her writings, beginning in 1890, focused on small, sociological details rather than grand facts, and are invaluable for modern social historians. Mrs. Earle wrote a number of books on Colonial America (with much concentration on the the New England region) such as Curious Punishments of Bygone Days. Alice Morse Earle could certainly appreciate her own quote regarding the inability to stop “the march of time” and enjoy “living in the moment,” thanks in part to a life-changing event that occurred in 1909. She nearly drowned off the coast of Nantucket while a passenger aboard the RMS Republic bound for Egypt. Shortly after departure and within a dense fog, her ship collided with the SS Florida. During the transfer of passengers, Alice fell into the water. This event impacted her health so severely that she died two years later. Tick-Tock Perhaps you are familiar with the fact that early Fredericktown was known for skilled craftspeople of many kinds ranging from furniture makers to glass artisans. The burgeoning Colonial era crossroads town on the western frontier was also known for its talented horologists. Now, like me, you may need a background in Latin and/or a small leap of imagination to see hour in horology, but if you do, you've pretty much deciphered the meaning of the profession based on the root “hora” (plural “horae”). Horology is the study of time and the art of making timepieces. Mount Olivet Cemetery is the final resting place to several horologists, but among the earliest is John Fessler, Jr. Mr. Fessler and his father are mentioned by name in an article written 80 years ago by D. W. Hering, the curator of the James Arthur Collection of Clocks and Watches at New York University, in which he discusses clockmaking in the 18th and 19th centuries, noting the rise and fall of the independent clockmaker, the movement away from quality items to clocks that could be sold cheaply, and the differences between public and domestic clocks. It originally appeared in the November 1937 issue of American Collector magazine, a publication which served antique collectors and dealers. Here is an excerpt from that article:  “To be a horologist, a man had to know both the science and the art of timekeeping; to be a clockmaker he had to be a skillful mechanic. From time to time a completely rounded man in science, art and handicraft appeared, such as Tompion, Graham, Harrison in England; LeRoy, Berthoud, Breguet in France; Ramsay, Reid, Smith in Scotland; Huygens in Holland; and Rittenhouse in America. In lesser degree there were many in America as well as elsewhere of measurable ability. In America we can cite examples that will show a wide distribution of such craftsmen and an interweaving of their output in a pattern that was spread over a broad territory. In clock lore as in that of furniture making and other industrial arts, certain names are so outstanding as to have become household words. Especially was this the case in the New England colonies where the fame of their clockmakers eventually rose to such a height as to produce the impression in later times that little ability or activity in that line was manifested anywhere else. But before the end of the 18th Century skillful clockmakers in other colonies had been producing their wares and acquiring a reputation. This was more marked in the Middle States and Maryland than in the colonies along the sea coast of the South. A clock was one of the few things not brought over in the Mayflower. If there was a clockmaker among the passengers he had no means of practicing his art except by importation of materials from Europe. Lack of mechanical facilities in America and high cost of materials for metal clocks, which had to be imported, drove would-be clockmakers of America to the production of wooden movements. These, however, were not attempted until the colonies had been growing for a hundred years and the compulsion under which they were made continued from about 1770 until about 1820. During this time these clocks were made almost entirely by hand and it is those only that can claim any attraction today as antiques. Toward the end of this period, with the aid of machinery that had then become available, wooden clocks were produced in such number and were so widely distributed that a wooden movement cannot now indicate either rarity or antiquity unless its date or maker is known. Handmade clocks, even those cheaper ones with wooden movements, were expensive and people who could afford to buy one could also afford to pay for an attractive case for it, and the long case or so-called “grandfather” clock became a prized piece of household furniture. Clockmaking as an industry related entirely to domestic clocks. Public clocks were installed by individual makers who, in many instances, carried on in a comparatively small way. Local makers of recognized ability constructed tower clocks to be installed in a town hall, a church steeple, or some public building in many of the thrifty New England cities, towns or villages, and also, though less commonly, in other sections of the country. Some of these clocks survive; others have been replaced by later ones. When an artisan built a public clock it was an important item in his own history and in the history of the place for which it was made. A clock of that nature was likely to be a chef d’oeuvre of its maker whose subsequent fame rested entirely upon that one work. A similar comment applies to an interesting public clock now in operation in the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C. Of this the Associate Director of the Smithsonian writes: ‘The clock movement was installed in the tower of Trinity Chapel, Evangelical Reformed Church, Frederick, Maryland in 1796-97. It was made there by Frederick Heisley. It was paid for by public subscription and was known as the Town Clock. It was removed about 1928 and replaced by an electric movement…It is a weight-driven, pin escapement, hour strike movement with a fourteen-feet pendulum with wooden rod and cast-iron bob. The frame is of hand-wrought iron, the wheels of brass, the drums of wood, and the weights cast-iron.’ Evidently this clock did duty faithfully on its original site for more than 100 years and, yet, so far as I know, no other clock by this maker is on record. “Willard,” “Terry,” and a good many other names suggest clocks to residents of the North Atlantic States who have no knowledge of clockmakers in other sections of the country, but there were makers in other sections, well known to residents there who knew nothing of the New England celebrities. Among such examples were the Fessler clocks in Maryland. John Fessler, Sr., learned the art of clockmaking in Germany or Switzerland and came to America sometime after 1750, settling in Lancaster, Pa. After serving in the Revolutionary War he moved to “Fredericktown” (now Frederick), Md., and established a business of making clocks. They are much in demand by collectors, especially in his local territory of Western Maryland. He died in 1820. One of the best authenticated and most fully recorded of early American clocks, with peregrinations and successive sojourns in three states is an example of a practice that was common with clocks of that kind and that period. The movement complete, without a case, would be placed on a shelf or bracket or could be hung up against the wall. As thus suspended it was, to all intents and purposes, a wag-on-the-wall but if the owner wanted a case for it he would have one made to suit his taste or his purse by a cabinetmaker in his own neighborhood. Our subject, John Fessler, Jr., learned the clock-making trade from his father, and would continue the family business upon the latter’s death in 1820. The Fessler story is atypical of the many German families that came to settle in early Frederick Town during the American Colonial period. To elaborate on Mr. Hering’s writing above, John Fessler was born in Switzerland in April, 1759 and immigrated with his parents and brothers to America in 1771, first living in Pennsylvania’s Philadelphia, then Germantown. He would move to Lancaster, where he likely apprenticed in the clock-making trade, although a few sources say that he came from a family of skilled craftsman of this ilk. Regardless, he took employment as a clock-maker there. From 1777-1782, John Fessler fought as a private in the Revolutionary Army. After the War, he relocated to Frederick Town, now a bustling crossroads, chock-full of skilled artisans including furniture and glass-makers. In the same year, John married a local girl, Anna Elizabeth Bach, and in 1783 opened a clock making and silversmithing business. The location is said to have been at the corner of W. Patrick and Publick (now Court) streets. The couple had four children, however, the first two (Heinrich and Elizabeth) would die in infancy. John, Jr. (also recorded as William John Fessler) was born July 2nd, 1787 and baptized in the town’s Evangelical Lutheran Church. Two years later, a sister Margaret would be born. I couldn’t find much on her aside from a marriage to George M. Conradt, Jr. in 1819. Mrs. Fessler, the former Anna Elizabeth Bach, was the daughter of German immigrants Balthasar and Rosina (Stump) Bach. Sadly, Mrs. Fessler would die prematurely in 1791, only in her 31st year. John Fessler, Sr. would remarry Elizabeth’s younger sister, Maria Barbara Bach. The couple would have three children, however two died as infants, and the third, a girl named Rosina, would die at age 13 in 1812. To compound the John’s pain, Maria Barbara would die in July 1801 at 30 years of age. Both marriages spanned only eight years each. Ironically, John Fessler, Sr. was dealt a hard lesson, over and over again, when considering Alice Morse Earle’s quotation regarding time when it comes to his loved ones. One can only assume that the bond between father and son (John, Sr. and John, Jr.) was exceptionally strong. Not only did John Jr. assist his dad in the family business, but he also stood as a steadfast family member throughout the entirety of John Fessler, Sr.’s adult life.

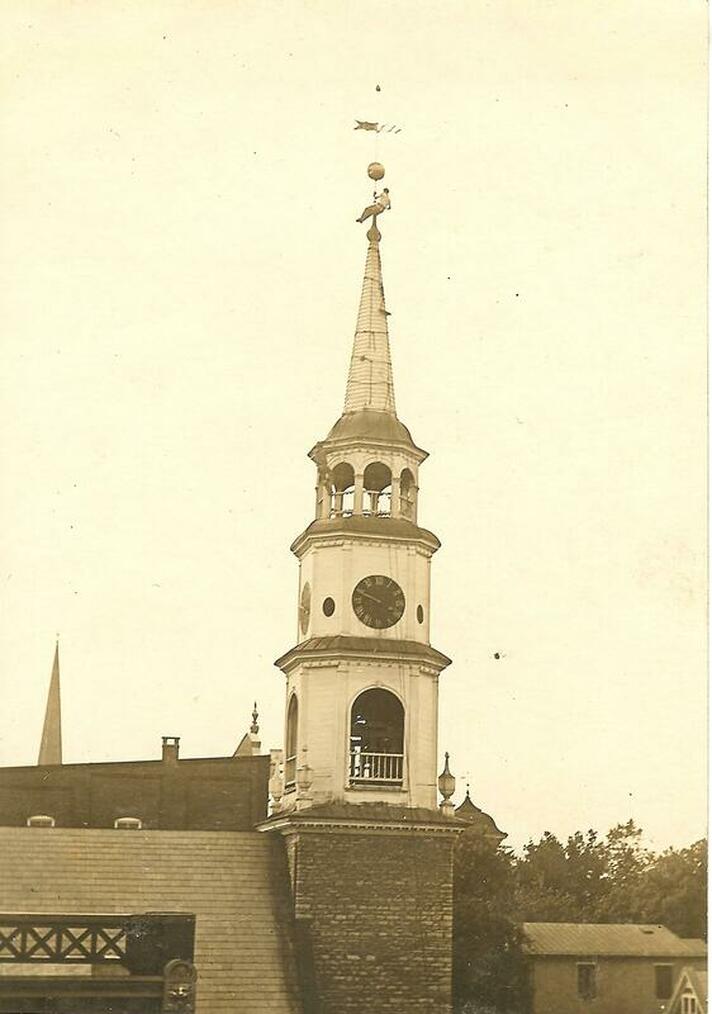

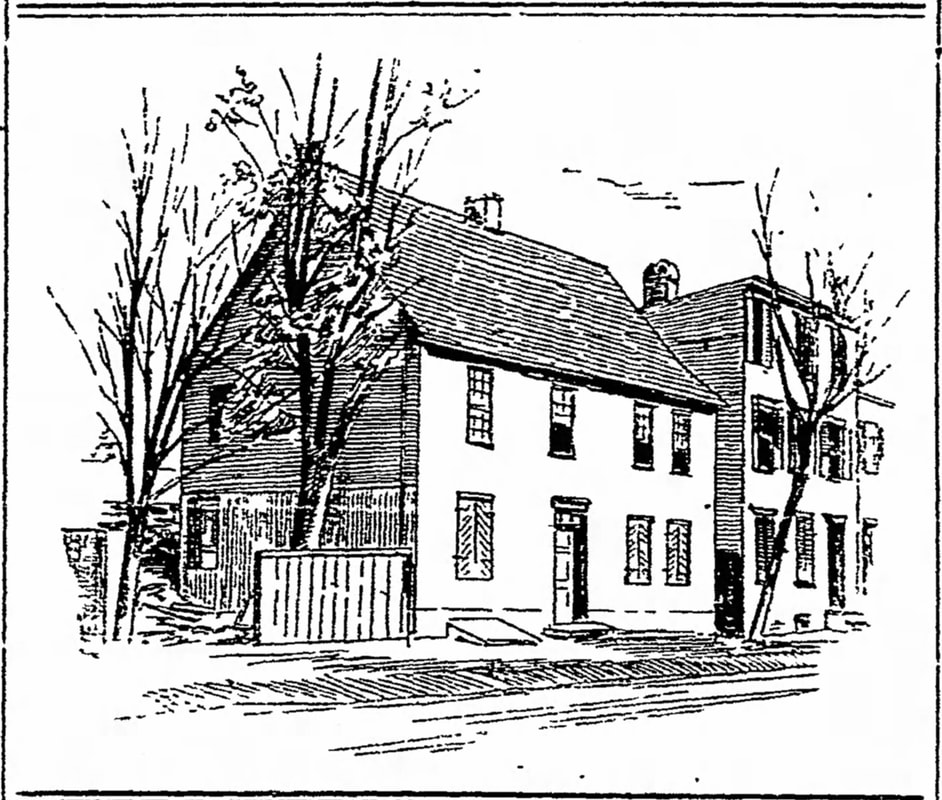

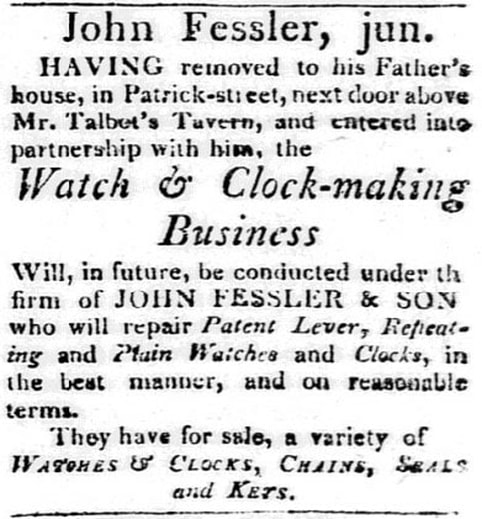

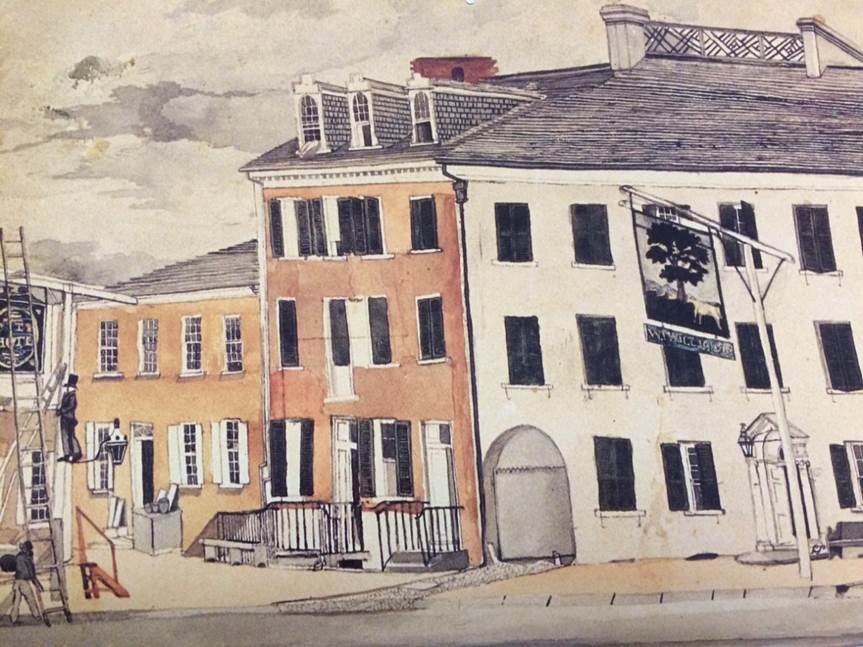

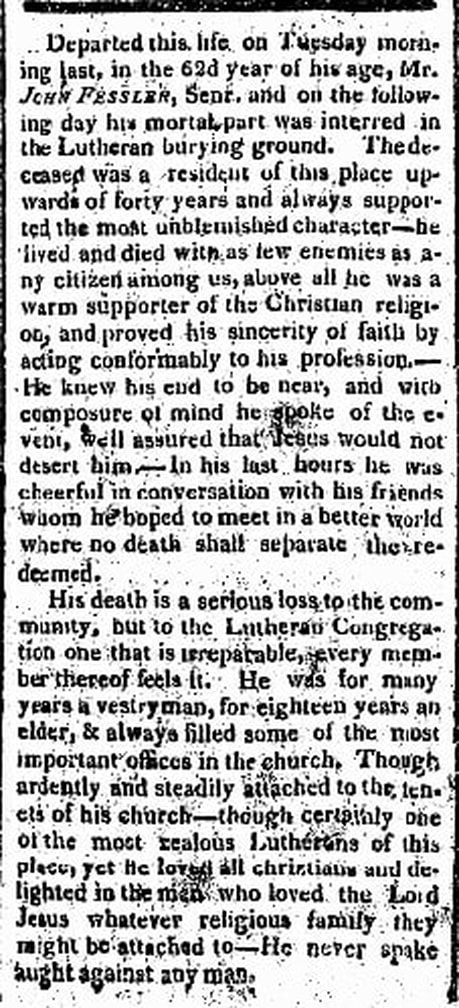

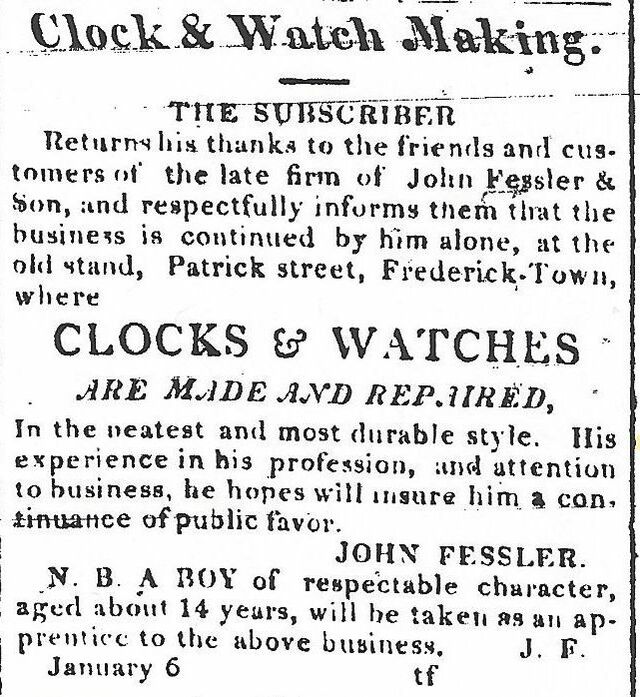

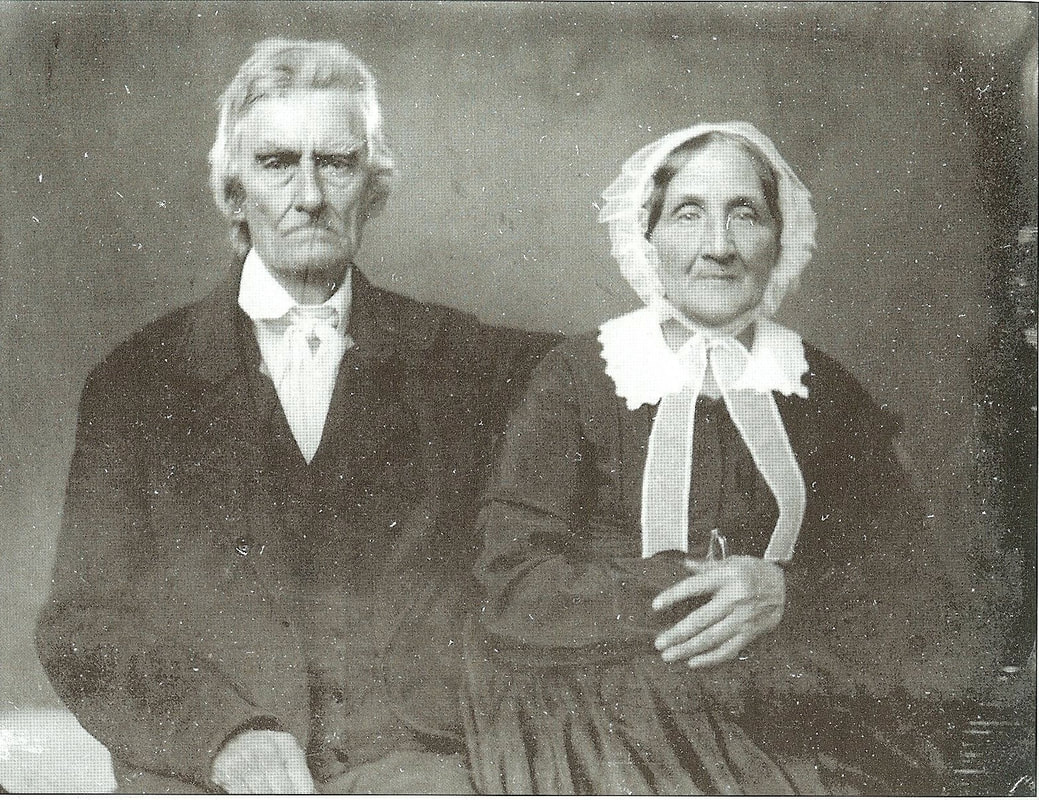

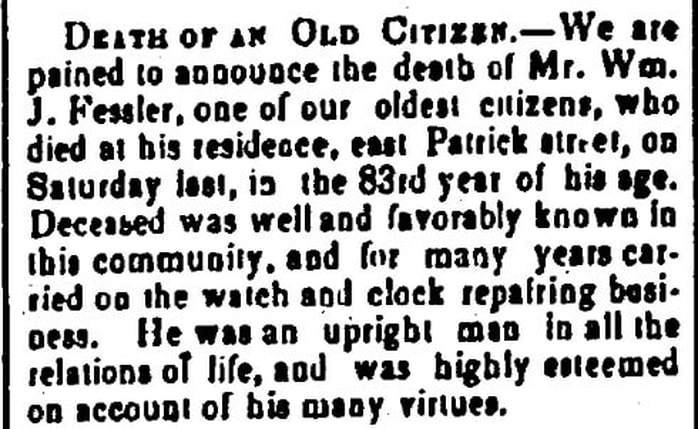

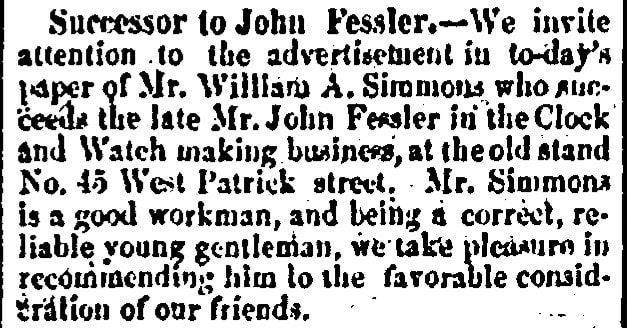

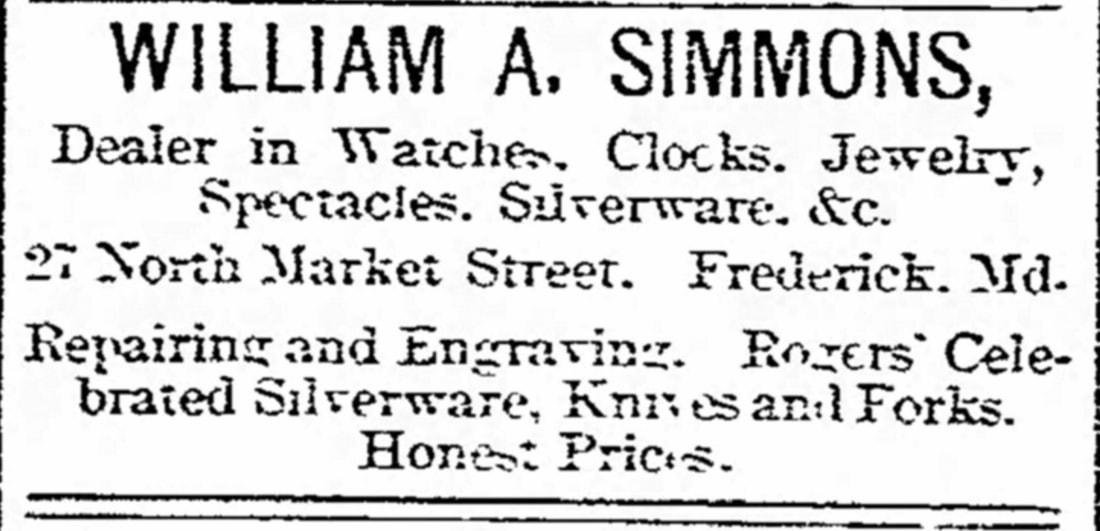

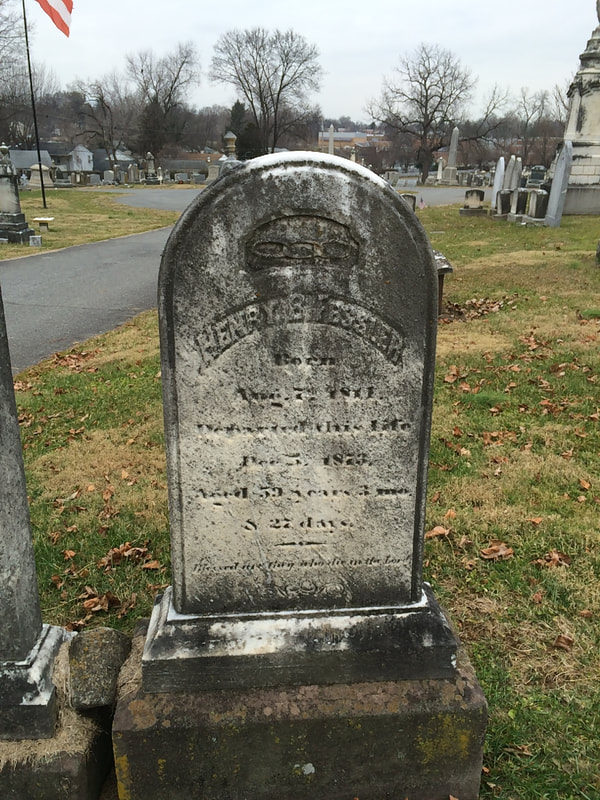

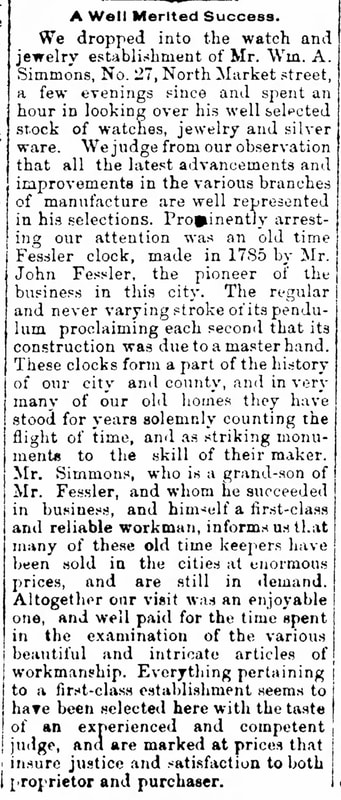

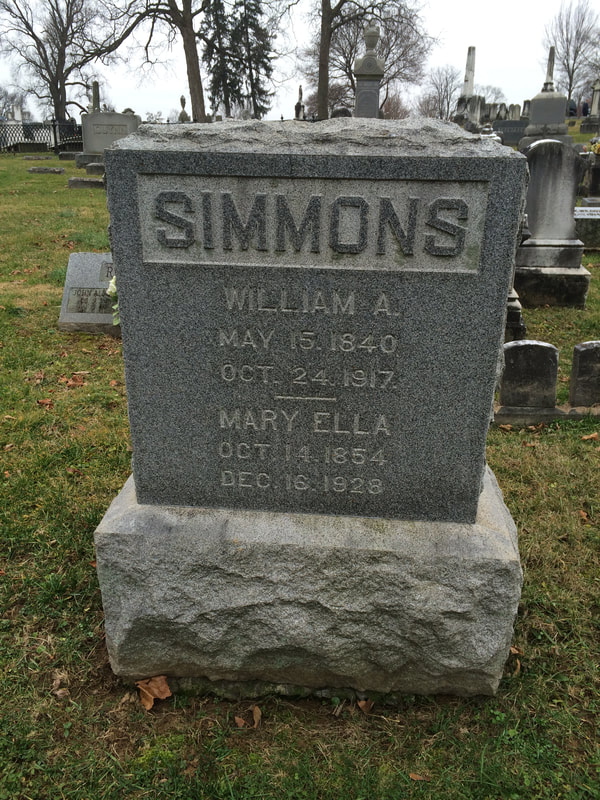

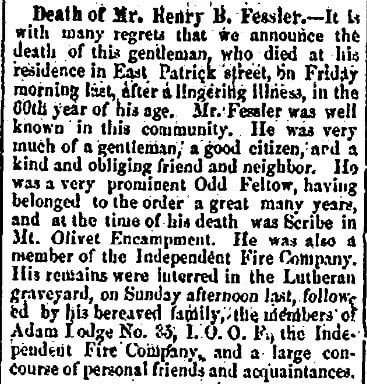

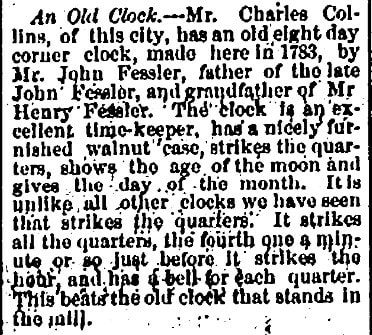

John, Jr. had assisted his father since childhood. One of his early responsibilities involved winding and oiling Frederick’s Town Clock, produced by fellow German and Revolutionary War vet, Frederick Heisley (1759-1843). This massive timepiece was placed within the spire of Trinity Chapel, located in the first block of West Church Street. To put things in context, I think I should give a brief overview of the fore-mentioned Mr. Heisely.  Compass made by Frederick Heisely Compass made by Frederick Heisely Frederick Heisely Frederick Heisely had also moved to Frederick in 1783 and set up a clock, watch, and mathematical instrument trade. He remained here about ten years, most of which spent located on South Market Street. Heisely’s prime offerings complimented the Fessler clocks as he specialized in surveyor compasses and other mathematical instruments, such as protractors, scales of different sorts, perch chains, pocket compasses, and sun dials. Around 1793, Heisely moved back to Lancaster, PA, and went into business with his father-in-law George Hoff. It is said that he returned to resume his own shop in Frederick in 1798, but this may be a bit fuzzy. Regardless, he was contracted by his own church congregation (German Reformed) to produce the clockworks to be placed in the spire of their church. Frederick Heisely may have bounced around as a journeyman, but would definitively move to Harrisburg, PA, in 1811, and worked with his two sons, George Jacob (1789-1880) and Frederick Augustus (1792-1875). Incidentally, we have a round-about connection with George J. Heisely as he is credited with putting the tune to Francis Scott Key’s “Star-Spangled Banner.” He was a soldier in Pennsylvania’s First Regiment during the War of 1812 and apparently shared his song book with fellow soldiers Ferdinand and Michael Durang. These two gentleman were amateur actors and the first to publicly perform singing the song with the accompaniment of the British drinking song “To Anacreon in Heaven”—and the rest is history (not to be confused with Heisely). In case you were curious as to the fate of Frederick Heisely, he would die in Harrisburg in 1843 and is buried in Harrisburg Cemetery. In early 1821, a register listing the Corporation of Frederick’s expenses for the previous year was printed in the Republican Gazette and showed that John Fessler and Son were paid $30.00 for winding and oiling the Town Clock. John, Jr. would continue to perform this task for years to come. Incidentally, the Heisely clockworks were eventually removed from Trinity Chapel in 1928 as mentioned in Mr. Hering’s article, and have been in the collection of the Smithsonian ever since. From that point forward, our Town Clock has been run by electricity. Fessler & Son On November 23rd, 1811, John Fessler, Jr. announced the opening of a shop in “the house of John Schley, opposite William and John Baer’s—a clock and watch making business.” This appeared in the Frederick Town Herald newspaper. Just over five years later, a formal business partnership with his famed father was publicized by way of an advertisement appearing in the Republican Gazette and General Advertiser in early 1817. The location given in this latter ad was that of a storefront on West Patrick Street, located to the west of Talbott’s Hotel, which in time would become known as the City Hotel. Today, the former Francis Scott Key Hotel sits on the site of both these former properties. The Fessler House, as it came to be known, was one of Frederick Town’s earliest domiciles, dating to the 1740’s. It served home to early surveyor, John Shelman, credited with assisting frontiersman Thomas Cresap in laying out the streets and lots for our oft-forgotten founder, Daniel Dulany of Annapolis. Through marriage, this house came into the Henry Baer family—John Fessler, Jr.’s in-laws as he had married Catharina Susanna Baer on January 28th, 1812. John Fessler, Sr. died on November 7th, 1820. His death was lamented in the local newspapers, and by noted Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht in a passage written later that day: “Died this morning at 4 o’clock in the 61st year of his age Mr. John Fessler, one of the most respectable inhabitants of this town.” The old clockmaker was laid to rest in the burying ground of his beloved Evangelical Lutheran Church, amidst his “sister wives” and the five children that predeceased him. I wasn’t able to glean much about John, Jr.’s professional life, but he continued producing quality work, including addressing the need came for smaller mantel clocks and pocket watches as tastes and styles changed. He was very active in civic life, and was continually elected as a city councilman representing Ward 2, and served as City Commissioner several times. The Fesslers went on to have five children: Rosina/Rosanna Catharina (1818-1903), Henry Baer (1814-1873), Anna Elizabeth (1816-1898), Caroline Rebecca (1828-1901), John William (1830-1837), and another son whose name is not readily known (1835-1837). Jacob Engelbrecht mentioned John, Jr. often in his recounting of municipal elections. The diarist also made two melancholy entries in the winter of 1837, a downtrodden time in which John and Susanna lost two sons in a week’s time: “Died this morning a son (youngest) of Mr. John Fessler aged about 2 years. This is the second child of Mr. Fessler that died within two weeks. The other was in the 7th year of his age. Buried on the Lutheran graveyard.” (Thursday, March 9, 1837 2PM) John Fessler, Jr. had been down this road before, and likely channeled his heartbreak into his work as he had seen done by his father before him. Unlike his father though, he experienced 50 years of marriage with Susanna (Susan). We are very fortunate that a picture of the couple (in later years) taken around the year 1860 survives in the magnificent collection of Heritage Frederick (formerly known as the Historical Society of Frederick County). Better yet, the collection has several examples of the Fessler “horological handiwork!” The U. Mehrl Hooper tall clocks display is a must see, and has been a permanent fixture of the museum for years. Susanna (Susan) Fessler died on Christmas Eve, 1862. It had been a rough fall and “time of times” already with the Confederate invasion of town by Gen. Lee and his Confederate Army in early September, followed by the battles at nearby South Mountain and Antietam. John, Jr. lived to see the end of the war and a return to a new normalcy. Amazingly, he had been born four years after the end of the American Revolution, and would die four years after the surrender at Appomattox. The clock would sound its last chime in the life of John Fessler, Jr. on July 2nd, 1869, two days before Independence Day. He had lived for 82 years, three months and nine days, but who’s counting. Fessler would be buried next to his wife in the old Lutheran graveyard of town. On November 15th, 1891, their bodies would be moved to Mount Olivet and reburied in Area H/Lot 5. After John Fessler, Jr.'s death, the family business would in essence continue for several decades, as it eventually passed into the hands of grandson William Augustus Simmons, son of John, Jr.’s daughter Rosina (Rosanna) Catharina (Fessler) Simmons. Fessler’s only son to live into adulthood, Henry Baer Fessler, trained as a lawyer but proudly performed the municipality’s appointed, honorable role as “town clock winder” when his father reached an advanced age. Henry B. Fessler’s early death in 1873 culminated in the end of the Fessler family care of the Town Clock for three-quarters of a century. "Time marches on!" you could say, but thanks to the Fesslers, many Fredericktonians were able to measure it through the beautiful clocks and watches they produced over a tenure spanning three centuries.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed