|

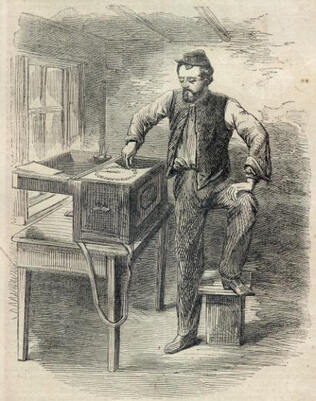

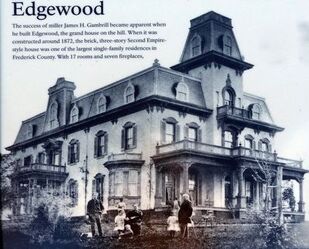

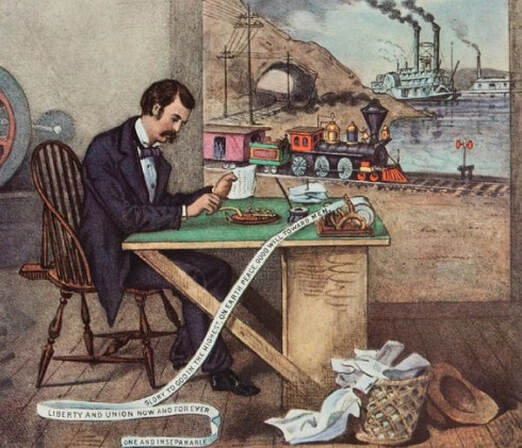

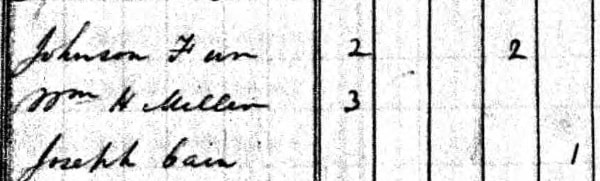

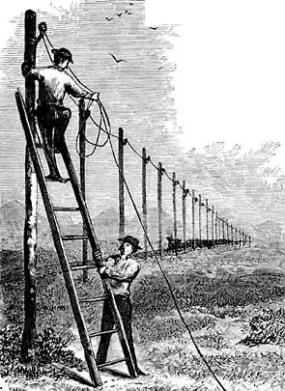

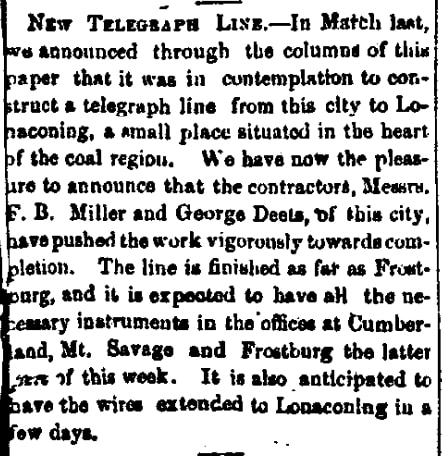

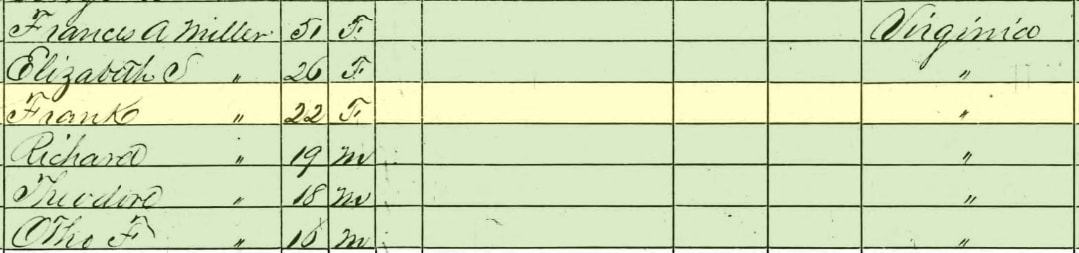

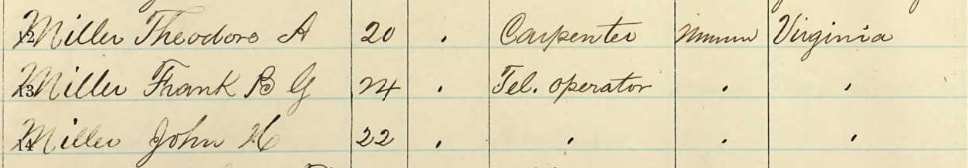

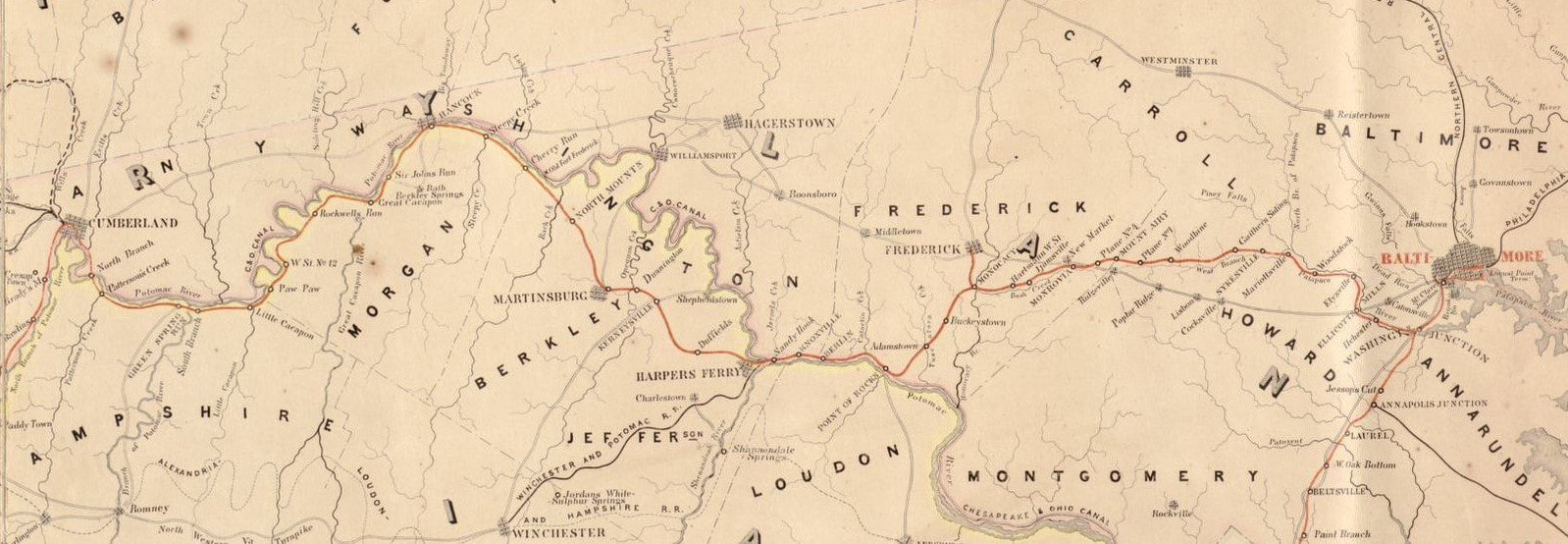

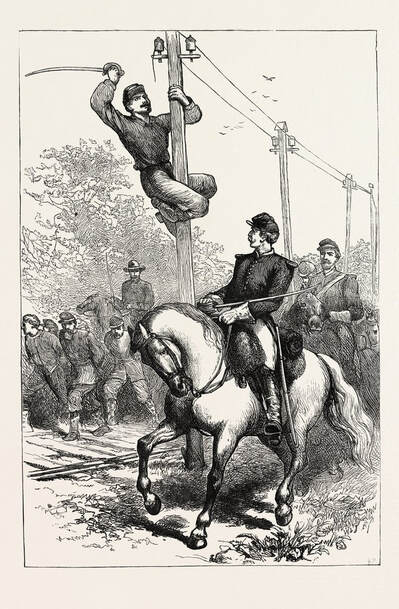

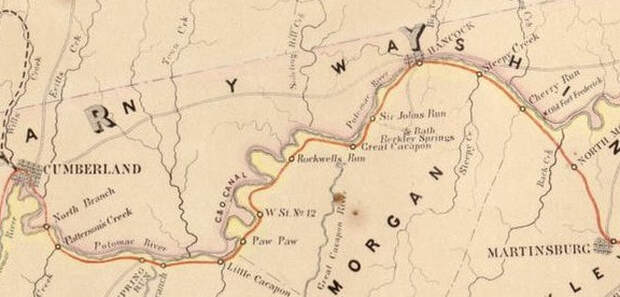

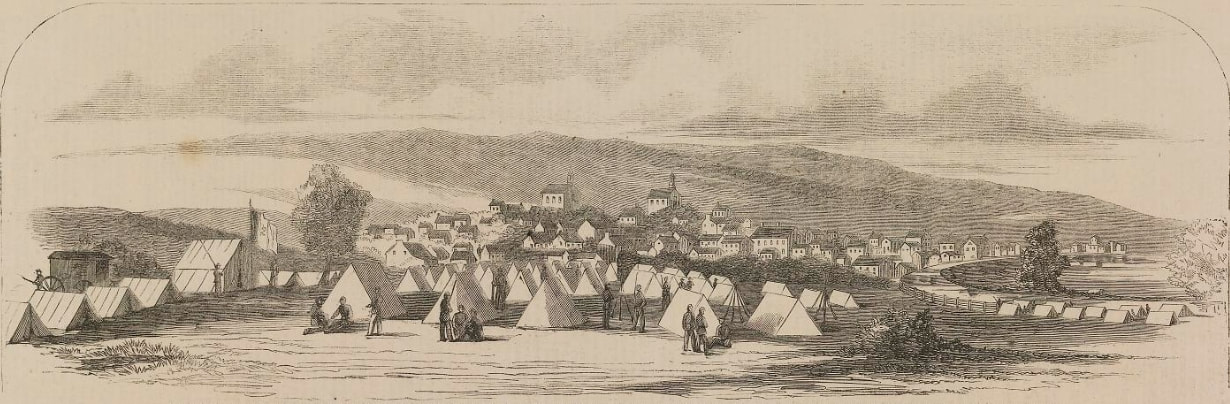

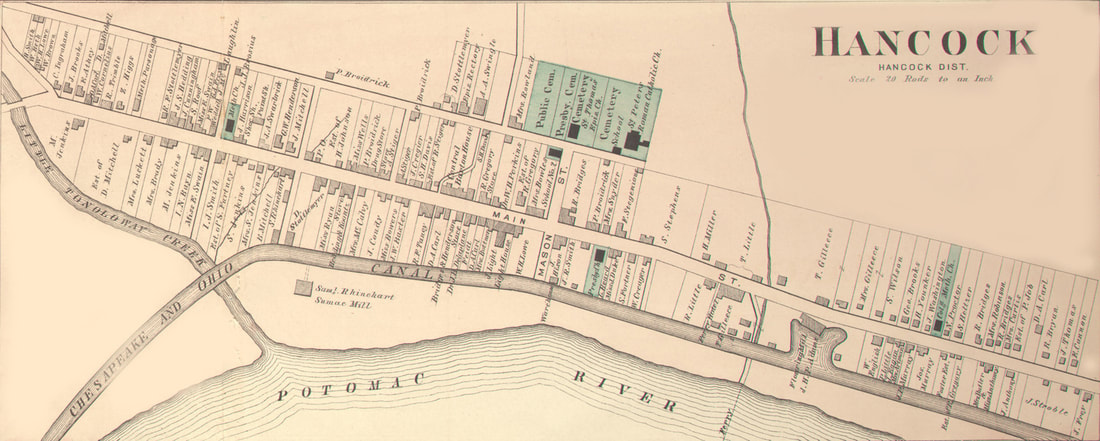

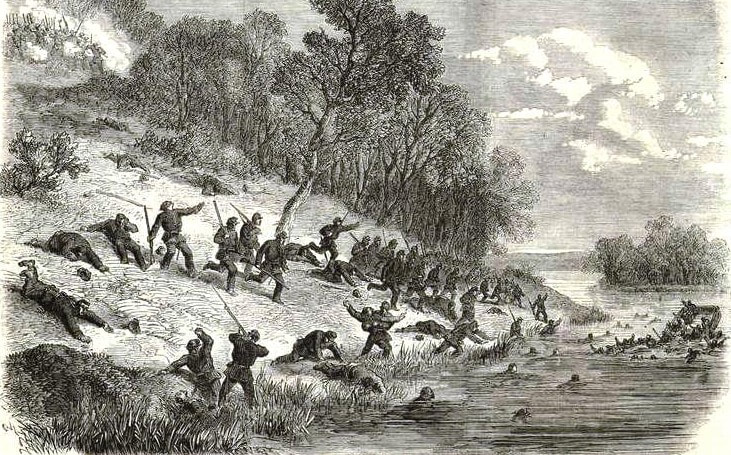

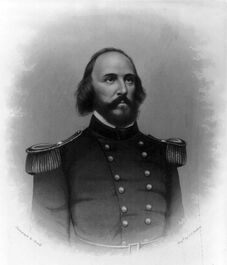

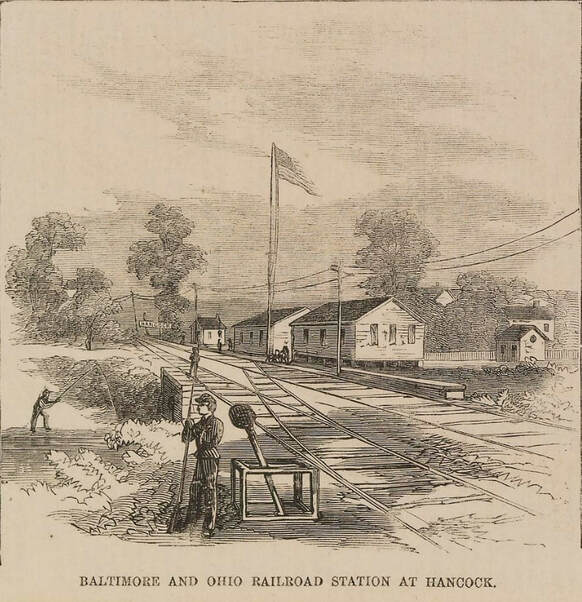

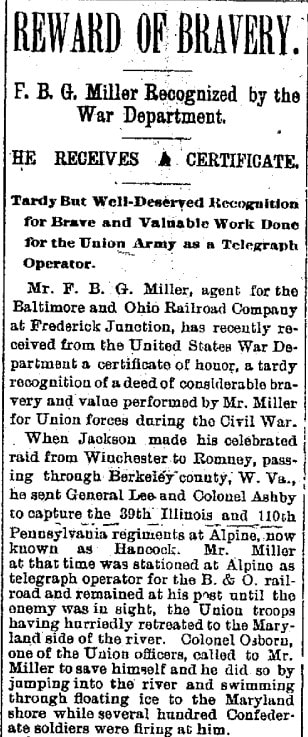

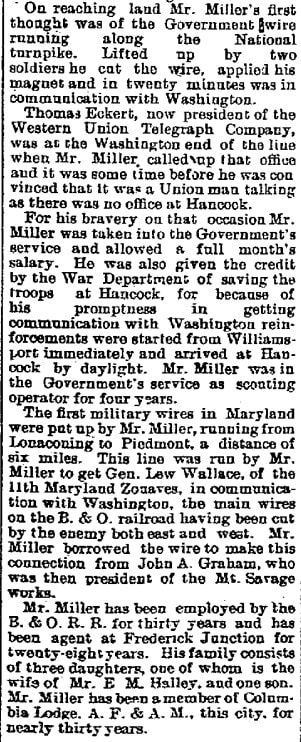

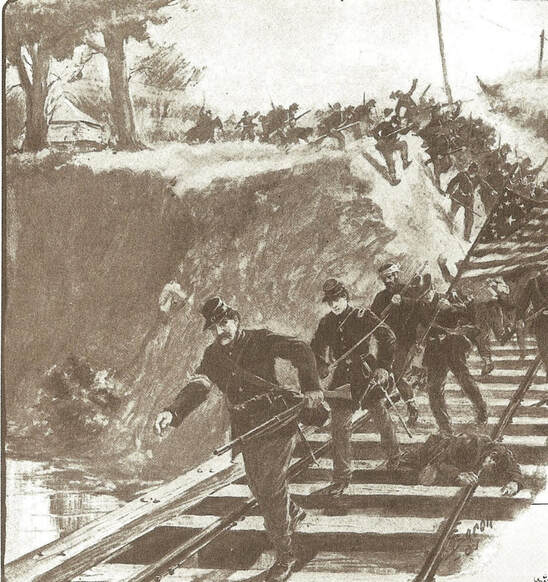

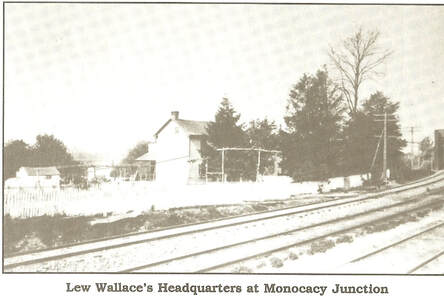

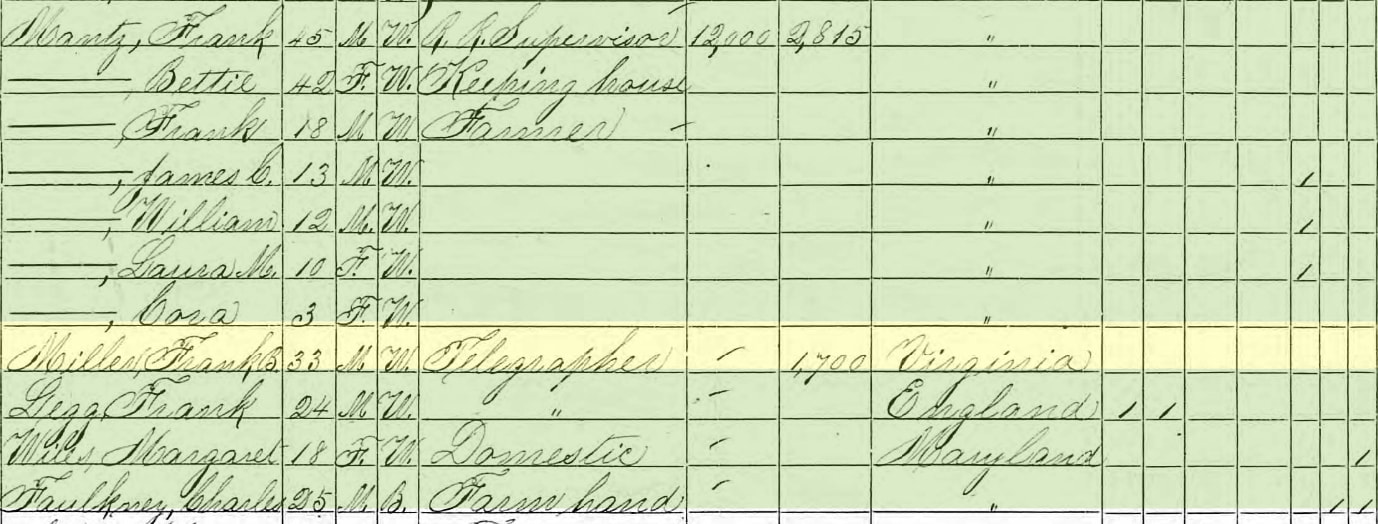

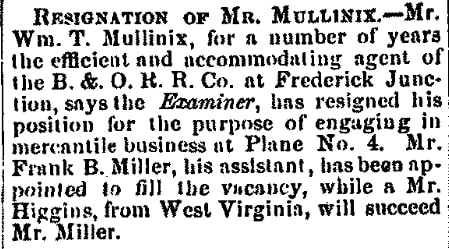

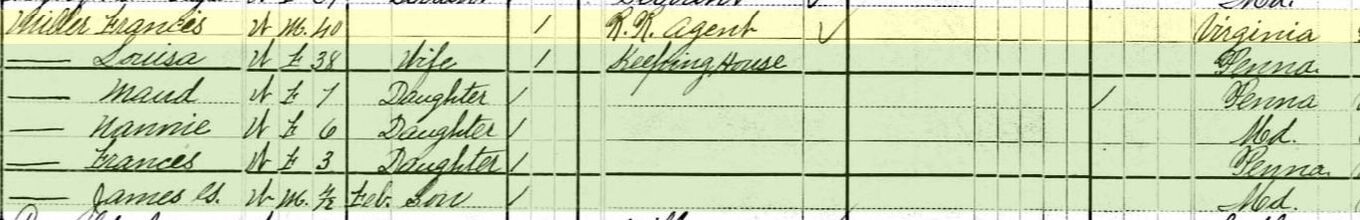

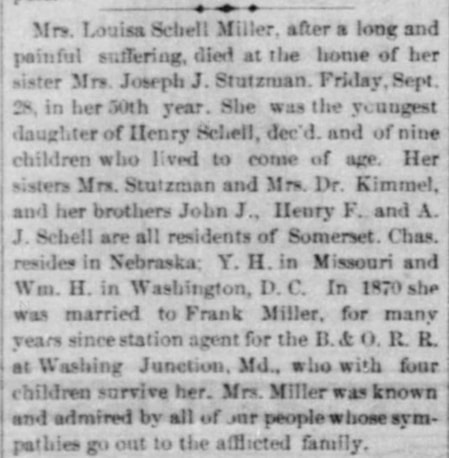

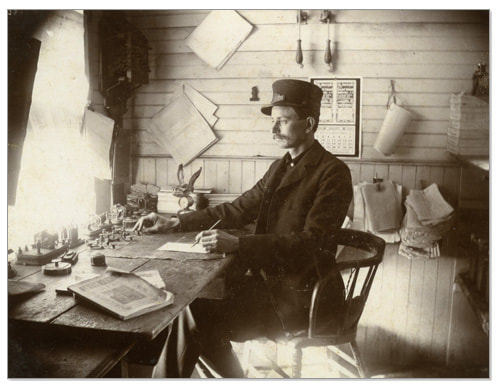

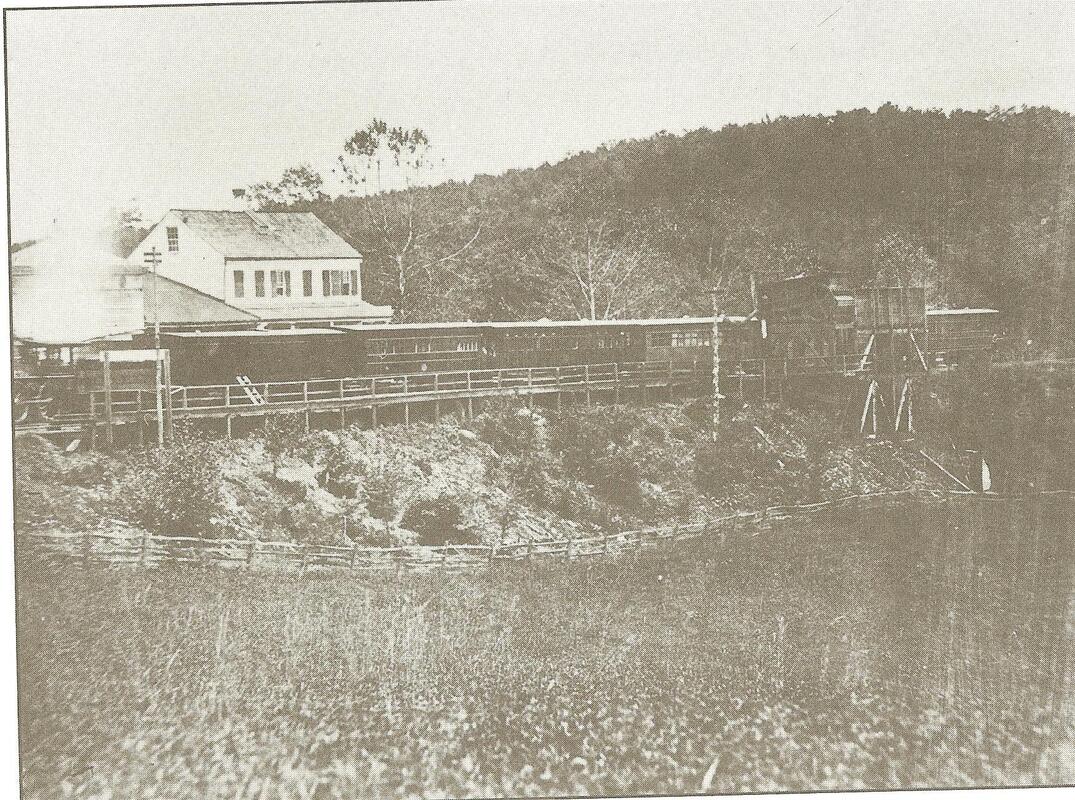

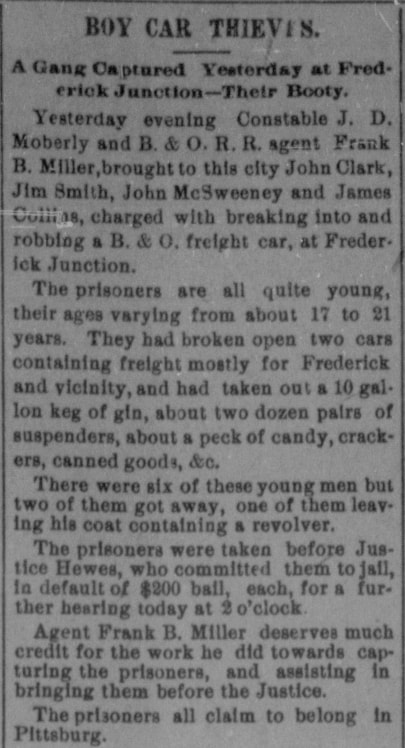

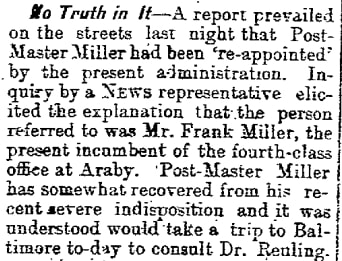

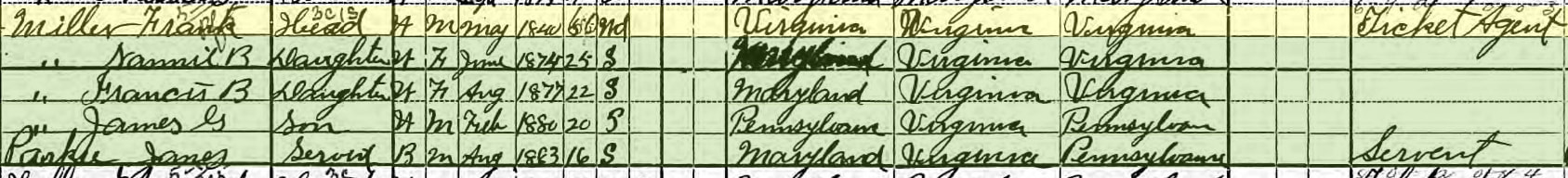

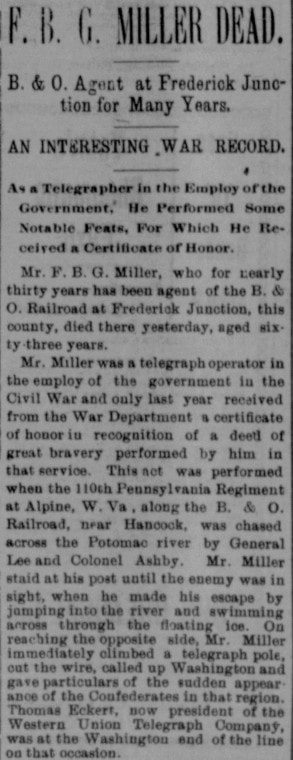

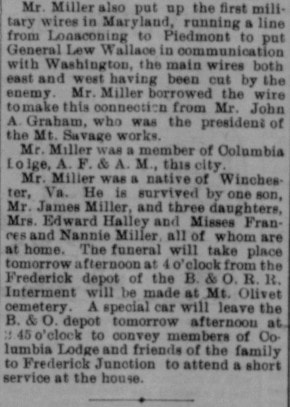

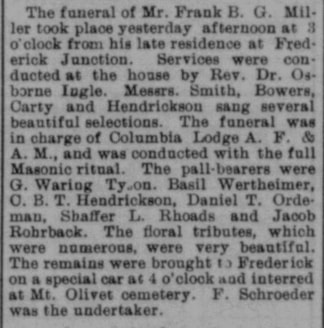

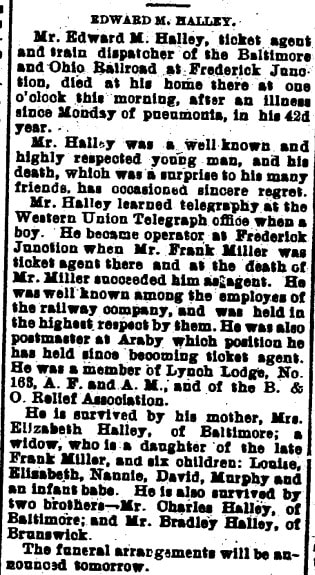

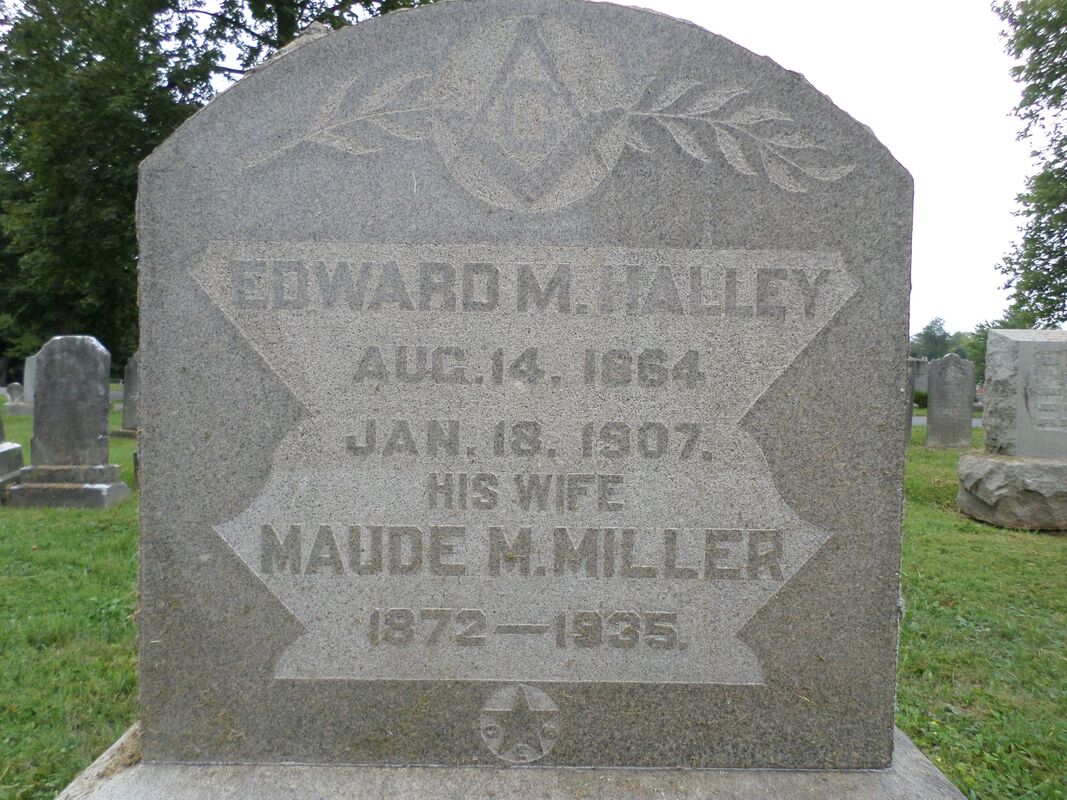

A few months back, an interesting visitor came to our Mount Olivet booth set-up at the Great Frederick Fair, (located under the West Grandstand). This kind lady approached me and told me she had been wanting to reach out to me in effort to share a tale of one of her ancestors buried in Mount Olivet. As historian of this amazing, historic garden cemetery, you can imagine that I’m always excited in learning more about our 40,000 plus inhabitants. This kind woman, Kristi Edens, even had gone to the trouble of putting some research together for me and printed a handful of newspaper articles, including an obituary for her GGG Grandfather—F. B. G. Miller. She also included a picture of Mr. Miller’s gravestone and a rough draft of a family tree pertaining to the subject, a long-time employee of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. So here I am a few months later to give you a brief glimpse into the life of Frances Bannister Gibson Miller, born in Winchester, Virginia on October 15th, 1838. He was the son of William Henry Miller (1808-?), a native of Pennsylvania, and wife Francis Ann Foster (1809-1866). Early life information is scarce, as I could not find the family in 1850 census, but they were indeed residing in Winchester in the 1840 US Census. I found my earliest account on this gentleman, better known as Frank, from an 1859 news article in a Cumberland, Maryland newspaper called the Maryland Civilian. It discusses young Frank’s amazing work ethic in running a telegraph line between Cumberland and Lycoming, Pennsylvania. Eventually he would make sure the line would reach Washington, Frederick and Carroll counties. This was the start of a lifelong profession. Frank’s father, William Henry Miller, had died somewhere before 1860, as he does not appear in the 1860 US Census with the family. We do not have either of his parents interred at Mount Olivet, so it’s been hard to piece info together aside from the semi-complete family tree Kristi shared with me. Frank’s mother, Frances Ann (Foster) Miller appears as head of household in the 1860 Census, in which he can be found living with his older sister Elizabeth and three younger brothers in Cumberland. I next found Frank Miller’s name in Allegany County’s Civil War draft registration roll books, which list his profession as a telegraph operator. He is listed as continuing to live in Cumberland. Here may be a good time to explain the once “state of the art” communication marvel of the telegraph and the profession of telegraphy that Frank had found himself engaged. A telegraph is a device for transmitting and receiving messages over long distances, i.e., for telegraphy. The word telegraph alone now generally refers to an electrical telegraph. Wireless telegraphy is transmission of messages over radio with telegraphic codes. A telegraph message sent by an electrical telegraph operator or telegrapher using Morse code (or a printing telegraph operator using plain text) was known as a telegram. The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad has a history intertwined with the first long-distance telegraph system set up to run overland in the United States.  The Baltimore & Ohio was the original telegraph line and was the right of way along which inventor Samuel F. B. Morse (1791-1872) constructed his experiment. Thereafter, many of the original expansion lines were built along the B&O. These lines were built through agreement between the original telegraph companies and the B&O. The telegraph companies were permitted to build the lines along the right of way, in exchange for providing service to the railroad. The lines might be the property of the railroads and operated by the telegraph company; or the lines might be owned by the telegraph companies, but at the end of the contract, if they did not remove the lines, they were surrendered to the railroad. The railroad controlled the most important thing for the networks—control of the right of ways. And the B&O controlled access to these right of ways in the mid-Atlantic, the most valuable market for the initial communications network. In 1861, when the Civil War broke out, the North/Union boasted a large network of telegraph lines, where the South had few lines. The North placed telegraph service under the War Department and used it to its strategic advantage. US President Lincoln and B&O president James B. Garrett (namesake of the Maryland county) developed a unique relationship in which the railroad and telegraph would assist the Union Army in communication and transport of troops and supply. In return, Mr. Garrett would receive protection from the army for his important investment consisting of trains, track, bridges and telegraph wires which had become regular targets for vandalism at the hands of Confederate raiders. The Civil War found Frank living to the east of Cumberland on the other side of Sideling Hill. He was in Hancock, Maryland, a town that grew up around the National Pike and later Chesapeake & Ohio Canal. The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad was a stone's throw away and across the Potomac River on the Virginia side. This settlement was called Alpine Station after the rail station positioned here, worksite for our subject Frank B. G. Miller. Hancock would see some of the first pitched action of the Civil War. The Battle of Hancock was fought during the Confederate Romney Expedition of the American Civil War on January 5th and 6th, 1862, near Hancock. Confederate commander Major General Stonewall Jackson began moving against Union Army forces in the Shenandoah Valley area on January 1st. After light fighting near Bath, Virginia (aka Berkeley Springs), Jackson's men reached the vicinity of Hancock late on January 4th and briefly fired on the town with artillery. Union Brigadier General Frederick W. Lander was in charge of Union forces here. The following passage comes from Peter Cozzens 2008 book entitled Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign: “By the morning of January 5, the temperature had fallen to 0 °F (−18 °C), where it would remain steady for the next three days. The Stonewall Brigade was brought up that morning, and Jackson aligned his men on Orrick's Hill across the flooded and ice-choked Potomac River from Hancock. At 09:30, Colonel Turner Ashby was sent across the river with a request for Lander to surrender; Jackson warned that he would shell and then capture the town if Lander refused. Upon meeting Lander, Ashby was instructed to tell Jackson to "bombard and be damned" and was given a written rejection of the offer. While Ashby returned to the Confederate lines, Lander ordered that civilians leave the town and assigned the 84th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment to serve as a fire brigade in case the coming bombardment started any fires. The 110th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment defended warehouses, and two pieces of artillery were positioned on a hill behind the town. The Confederate cannons opened fire at about 14:00, and a sporadic artillery duel which inflicted no casualties continued until dusk. A Confederate detachment under Colonel Albert Rust destroyed a bridge over the Big Cacapon River belonging to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, while another detachment failed in an attempt to destroy a dam upriver from Hancock. While Jackson opened January 6 with a bombardment of Hancock by the Rockbridge Artillery, Lander still desired to take offensive action against Jackson. He asked Major General Nathaniel P. Banks to either cross the Potomac in Jackson's rear or to send him reinforcements, with which Lander would attack the Confederates directly. Banks had ordered Brigadier General Alpheus Williams's brigade to march towards Hancock on January 5, but sent the request for offensive action through Major General George B. McClellan, who viewed it as too risky and rejected it. Later that day, Jackson attempted to cross the Potomac at Sir Johns Run, but was repulsed. Having damaged the telegraph lines in the area, Jackson abandoned the attempt to take Hancock on January 7 and withdrew. The exchanges of artillery fire had caused little damage. The National Park Service estimates that the two sides combined suffered about 25 casualties during the fighting. Here is where two interesting connections to Frederick, Maryland come into play. First, the above mentioned Gen. Frederick Lander would eventually have his name grace a post office in southern Frederick County on Potomac River and on the west side of Catoctin Mountain. Of course this is Lander, a small hamlet that boasts a canal lockhouse at lock 29 near mile marker 50.8 Today, you can find a popular boat ramp here too. As for Gen. Lander (b. 1821), he was a transcontinental United States explorer, a prolific poet and had recently married a top stage actress from Great Britain. Likely due to the fatigue of the winter campaign of January and February, 1862, Gen. Lander contracted pneumonia and his gifted life would be cut short with his death on March 2nd, 1862. The second connection of note involved Frank B. G. Miller who was serving as the telegraph operator for Hancock at that time. The railroad station was located across the Potomac at Alpine Station. Here is an article from 1899 that explains the heroics he would employ during the Battle of Hancock in early January, 1862. Pretty cool stuff and the imagery of someone swimming across the Potomac in the dead of winter is one thing, but doing so amidst ice chunks in the water, and bullets whizzing by in the air above is awe-inspiring. And if that wasn’t enough, he didn’t even have time to dry off and change clothes, before climbing a telegraph pole to jerry-rig the communication line to Washington, DC. This seemed to be the most exciting action during the war for Frank Miller. Following the end of hostilities, he came to Frederick and served as the assistant telegraph operator at Monocacy Junction, another place that saw plenty of activity during the American Civil War. The pinnacle was the July 9th Battle which is known in history books as "the Battle that Saved Washington, DC." This conflict was mostly the result of telegraph and transportation lines of the B & O. Word was communicated via the telegraph to Baltimore that an unusual Confederate Army contingent had suddenly appeared in Martinsburg under Jubal Early in early July, 1864. This Rebel group headed east across to Potomac to Sharpsburg, and then Boonsboro crossing South Mountain to Middletown and eventually reached Frederick in July where they promptly requested a ransom of $200,000. Gen. Lew Wallace commanded Union troops here, hastily brought in from Baltimore to square off with Gen. Early's men. Interestingly, Miller had installed some of these same telegraph lines under Wallace earlier in the war in the western part of the state. A battle would rage at the Monocacy Junction, a few miles south of Frederick, on July 9th. The fighting could clearly be seen and heard from vantage points throughout town, including our fair cemetery, only in its 10th year of use at the time. One of the central areas of action of the battlefield area was the Monocacy Junction itself and associated buildings. Many fascinating things happened here during and after the battle, including action around the train station at the actual junction itself, Lew Wallace's command headquarters and the B& O Railroad Bridge across the river. A surprise visit from Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and Gen. Philip Sheridan occurred here on August 6th, 1864 for a secret planning meeting. One of the longest inhabitants though would become Frank Miller. Frank started as assistant telegraph operator, but would take the top job after his boss, William T. Mullinix (1849-1910), stepped down in 1880. It appears from other articles that he performed this top job as B & O Rail Agent with a high level of professionalism and creativity. On the personal side of life, Frank lived at the Junction but records show that he had purchased a 4-acre property between the railroad and Bush Creek on the east side of the Monocacy, but sold it in 1870 to Ann Johnson, wife of Worthington Johnson. Frank soon married Louisa Marie Schell (b. 1838 in Somerset, PA) around 1871. The couple would go on to have four children: Maude Mary Miller (1872-1935), Nan Boardman Miller (1875-1960), Frances B. Miller (b. 1877), and James H. G. Miller (b. 1880).  Frank's son, James, was named for neighbor and friend James Henry Gambrill who lived across the river from the junction in the large mansion once known as Boscobel House and Edgewood. The Gambrills owned the nearby Araby Mill and the Frederick City Mill (destined to become the Delaplaine Art Center). Now part of the Monocacy National Battlefield, the old Gambrill mansion houses employees of the National Park Service Historic Preservation Training Center. Sadly, the Miller family would undergo a great degree of sadness in the late 1880s as Louisa would become sick and required care from her sister in their hometown of Somerset, Pennsylvania. Here, Louisa succumbed to her illness on September 29th, 1888. She was laid to rest in Somerset's Husband Cemetery. Meanwhile, Mr. Miller took on the task of raising four children into adulthood. Mr. Miller threw himself into his job even more, one he already had great passion. He even foiled a robbery one night while on the job. In addition to his duties as a rail-road agent for the B & O, Miller would also be appointed the postmaster of the Araby Post Office. He would eventually be replaced in his Railroad agent position at Monocacy Junction by his son-in-law, Edward M. Halley, who had married his daughter Maude. Frank served as a ticket agent with the railroad in his final years. He would die on September 12th, 1900. He is buried in a small lot (#36) on Area F. This plot is owned by Columbia Lodge Number 58 of the Frederick Masonic Lodge. Frank was a member for nearly 30 years. Mr. Miller is one of four individuals actually buried within the Masons’ lot which was originally purchased in 1858. Staying true to form, he continued his streak of avoiding land property ownership. Frank G. B. Miller's obituary found in the Frederick paper included tales mentioned earlier of his early career in the telegraphy business, and his Civil War heroics and bravery under fire. His obit was carried in both the Baltimore and Washington newspapers where I'm sure many knew him from his connection to the B & O. Mr. Halley would be appointed as Araby's Postmaster just a few weeks after the passing of Frank Miller. Mr. Halley died just seven years after his father-in-law in 1907, thus ending the family's reign at "the Junction." Both Maude and Edward are buried in Mount Olivet’s Area H/Lot 29.

1 Comment

Kristi Edens

11/9/2021 12:16:05 am

Thank you so much for sharing our story. When I was a little kid, I always thought my great-grandmothers were exaggerating things that their grandparents did, but this one turned out to be totally true. It is so awesome to see it published.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed