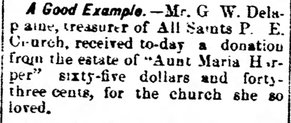

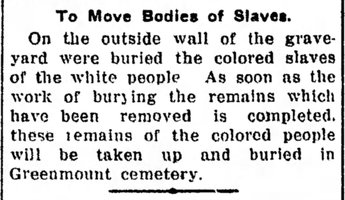

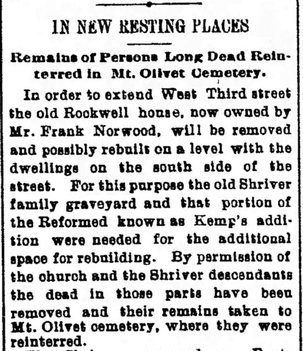

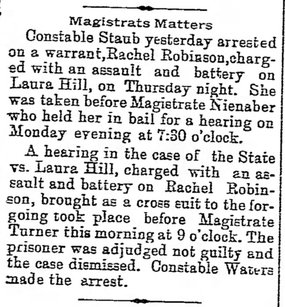

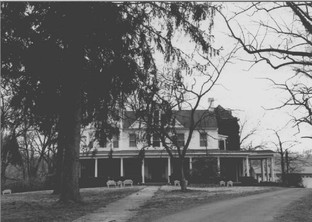

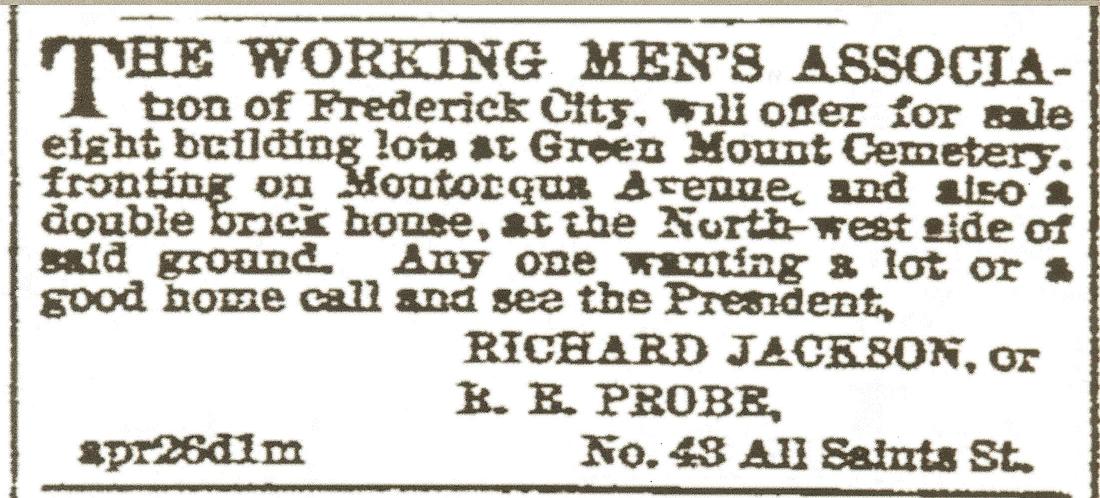

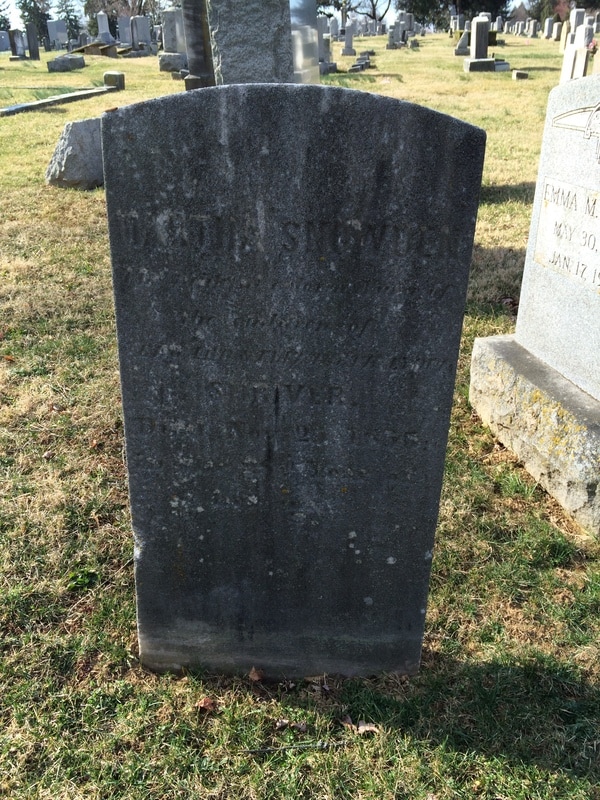

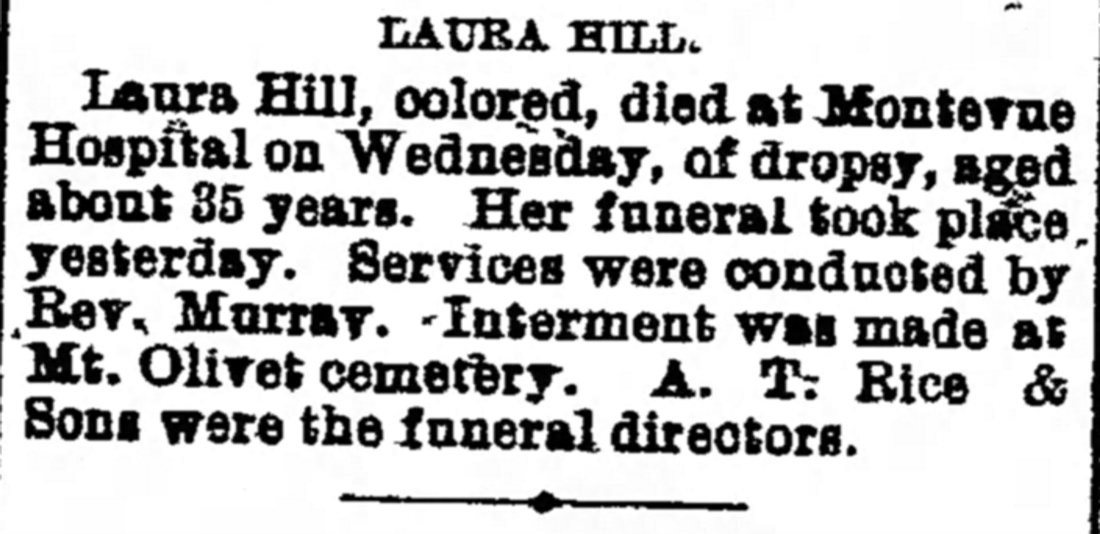

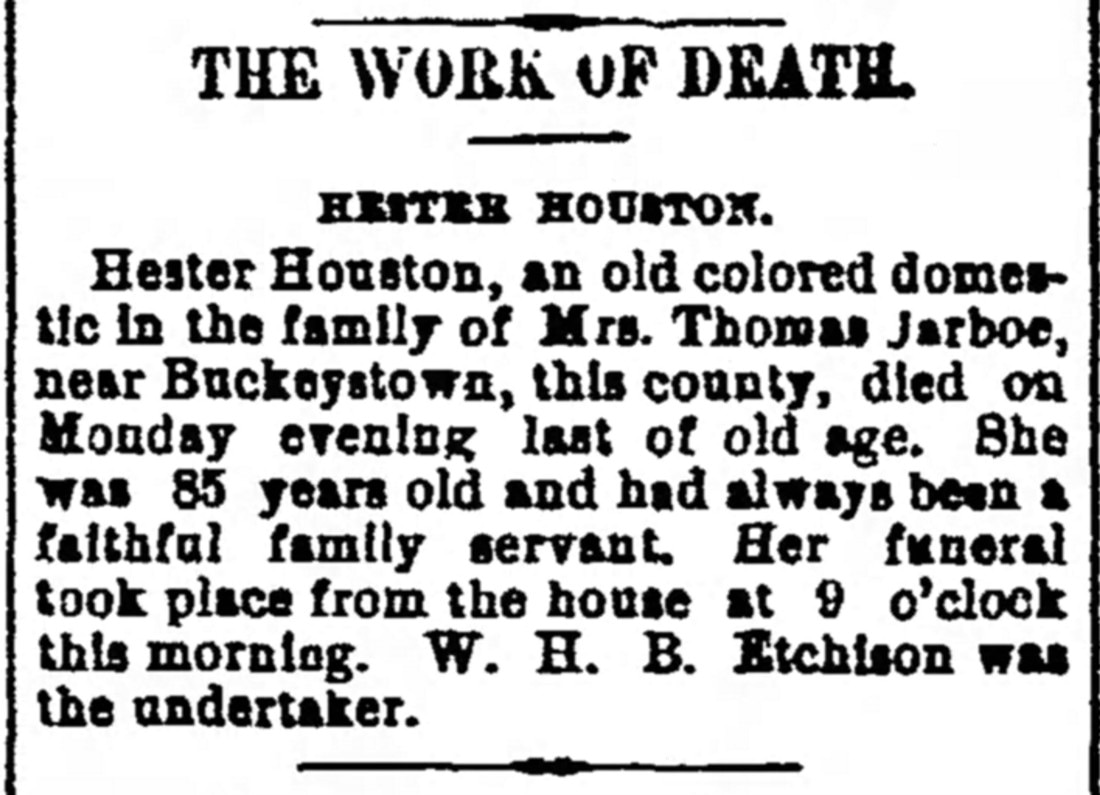

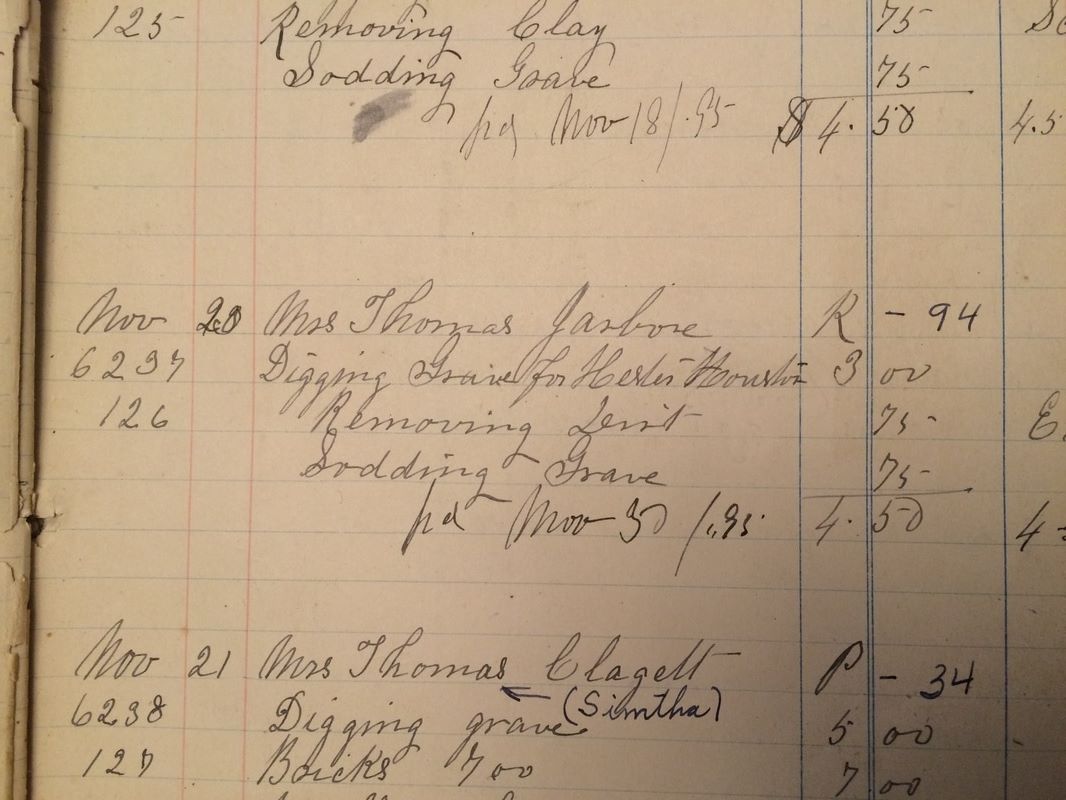

(Part II) Sidestepping a Color Barrier: The first Black Residents buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery3/5/2017  Grave of Dr. Ulysses G. Bourne, Sr. (1873-1956) in Fairview Cemetery Grave of Dr. Ulysses G. Bourne, Sr. (1873-1956) in Fairview Cemetery In part one of this story, I explained the preface of searching for the earliest Frederick residents of color to be buried in Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery. The rural cemetery opened in 1854 and specifically catered to Frederick’s white community, an unspoken and understood practice not only here and the Deep South, but in many places in the North as well. Separate burying grounds, or sections within established graveyards, had been set up by churches or beneficial societies for the black populace. This was no different with how churches had evolved, marking a color divide with religion (ie: the Methodist Episcopal Church vs the African Methodist Episcopal Church). The same was true here in Frederick as well. From before the time of the Civil War up through to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, many cemeteries would remain segregated with “unwritten” and, in some cases, “written” rules to back the claim. Today, Mount Olivet is the largest cemetery in Frederick County, open for over half a century operating without discrimination in burying people regardless of color, creed, religion, sex and national origin. At the same time, Fairview Cemetery, located on E. Church Street extended/Gas House Pike continues a proud tradition of service as the predominant “black cemetery” of town. This is more of a historical and cultural precept in the time following the civil rights movement. The cemetery continues to cater to black citizens, especially those with long family ties to the community. Within its gates, the visitor can find outstanding leaders of our past such as Dr. Ulysses G. Bourne (Frederick’s first doctor), John W. Bruner (Frederick’s first Superintendent of Colored Schools), Rev. J. W. Townes (Faith and Community leader/First Baptist Missionary Church), Esther E. Grinage (Educator and Kindergarten Foundress), William O. Lee (Frederick’s First Alderman) and Albert V. Dixon (Frederick’s First Black Undertaker). Although Fairview’s monuments may not be as grand as many found in Mount Olivet, the ”life’s work” of what each of these gentlemen did for our Frederick community certainly rivals, if not surpasses, that done by some of our gilded heroes—particularly the big three—Francis Scott Key, Gov. Thomas Johnson, Jr. and Barbara Fritchie. And speaking of the Thomas Johnson, in the last article I talked at length about Mrs. Maria Harper, associated with the extended family of Maryland’s first governor and Frederick’s All Saint’s Church congregation. In 1913, the mortal remains of Gov. Thomas Johnson, Maria Harper and over 300 others were removed from the colonial-era All Saint’s Cemetery in downtown Frederick, and reburied in Mount Olivet. This was certainly a historic occasion as Maria gained entrance into Mount Olivet Cemetery and became one with thousands of white residents resting in peace since the cemetery first opened its gates nearly sixty years earlier.  Frederick News (May 13, 1885) Frederick News (May 13, 1885) And speaking of the Thomas Johnson, in the last article I talked at length about Mrs. Maria Harper, associated with the extended family of Maryland’s first governor and Frederick’s All Saint’s Church congregation. In 1913, the mortal remains of Gov. Thomas Johnson, Maria Harper and over 300 others were removed from the colonial-era All Saint’s Cemetery in downtown Frederick, and reburied in Mount Olivet. This was certainly a historic occasion as Maria gained entrance into Mount Olivet Cemetery and became one with thousands of white residents resting in peace since the cemetery first opened its gates nearly sixty years earlier. Maria Harper may have been the earliest-born black female resident to be buried in Mount Olivet, but she was not the first. To seek out whom that distinction belongs to, I have had to dig deep (no pun intended). Due to many factors such as lost or missing records, we may never have the true answer to this question. But we also may be sidetracked due to a record that was deliberately lost, or deliberately “unwritten.” I will explain this statement further into our discussion. No matter the situation, I am pleased to report that my total findings of known early black residents in Mount Olivet has doubled over my last few weeks of research—from three to six definitive cases bearing proof. Because of this increase, I have decided to turn a two-part article into a three-part article. I seek not to overwhelm you the reader, as I regularly push internet blog and etiquette norms with regard to article length.  Frederick News (11/26/1913) Frederick News (11/26/1913) Backstory First off, I want to give a little more context into the history of black burial as it pertains to Frederick City. In part one of this article, I discussed the myriad of slave and family cemeteries which could be found across the county. I also presented information regarding isolated burials of blacks in the older “white church congregation” graveyards of town—places such as St. John’s Cemetery and the fore- mentioned All Saints Cemetery, with adjoining “Old Hill” Burying Ground. Re-interment of bodies that were originally buried in the latter “Old Hill” ground (also referred to as the “colored people’s graveyard”) followed that of the whites once buried in All Saints. While the whites, plus one black (Maria Harper), headed south of town to Mount Olivet in fall of 1913, the black bodies were transferred “uptown” to a new home—Greenmount Cemetery. Greenmount Cemetery was incorporated for the purpose of aiding Frederick's black residents under the leadership of The Working Men's Association of Frederick. This occurred in 1880, as the black beneficial society purchased a "lot of ground for burial purposes" from Gideon and Julia Bantz, situated on the south side of Montonqua Avenue, today’s W. Seventh Street. A gentleman named Richard Jackson signed the deed as the association’s president. In the 1880 census, Jackson is listed as a black shoemaker, born in Virginia, and living with his wife and three daughters on W. All Saints Street.  Greenmount Cemetery as captured in this zoom from an 1899 photo taken from the atop Trinity Chapel, looking nw across Court Square. The white house to the immediate right of center was the cemetery keeper's house that once sat on the south side of W. 7th Street (which bisects the photo left to right heading nw.) Greenmount Cemetery and its monuments can be seen below and to the left of the house as the property stretches to the southwest from this particular angle. Note the hedgerow separating the cemetery property from Groff Park to the west (future Hood College) and Emma Smith's purchased parcel to the east (future City Hospital site). In 1898, The Working Men’s Association changed its name to The Working Men's Stock Company. The Greenmount Cemetery quickly overtook another beneficial society-formed “colored cemetery” located roughly six blocks to the east, between E. Sixth and E. Fifth Street, on Chapel Alley. This was the Laboring Sons Cemetery, formed in 1837 by a group of free black laborers and craftsmen residing in and around Frederick. This group had purchased their cemetery property in 1851, and burials soon commenced after. A schism of some sort occurred in the early 1860’s within the Beneficial Society of Laboring Sons, apparently causing two-thirds of the members to defect. In turn, many of these folks were responsible for establishing the Working Men’s Association and subsequent rival cemetery. All the while, Maria Harper had been buried in All Saints Cemetery in 1884, and would make her way into Mount Olivet less than 30 years later in 1913. However, there are at least three other documented cases involving black women being buried in Mount Olivet before this time (1913). In addition, a fourth incident involves the first burial of a black male.  German Reformed Cemetery (located at the corner of Bentz and W. 2nd streets) German Reformed Cemetery (located at the corner of Bentz and W. 2nd streets) Martha and Abe An entertaining article in the May 19th, 1904 edition of the Frederick News announced that the remains of the Shriver family had recently been successfully reinterred within Mount Olivet cemetery. A family plot belonging to Judge Abraham Shriver (1771-1848) and son Gen. Edward Shriver (1812-1896) was located along N. Bentz Street, specifically on the west side, just south of today’s Rockwell Terrace thoroughfare. The Shriver family graveyard was an addition to the existing German Reformed Burying Ground, and was said to have been “a quiet, pretty plot, enclosed with an iron railing, and shaded with tall pine trees.” Gen. Shriver was associated with a local militia unit and the Union Army’s Potomac Home Brigade during the Civil War. His home was only a block and a half away in Courthouse Square. Another family member buried here was Charles Edward Shriver. Charles fought with the Confederacy, falling in battle in August, 1863 at the tender age of 18.  Frederick News (May 19, 1904) Frederick News (May 19, 1904) At the time of the article’s writing, a plan was in effect to extend W. Third Street to the west from Bentz Street (today’s Rockwell Terrace). The namesake home of Elihu Rockwell was originally positioned on the west side of Bentz in the street bed that exists today—it had to be moved to the south of its present location. Thus came the need for the Shriver family and others to be moved. Since these bodies had to be re-located anyway, why not re-bury the inhabitants in the newer, prime cemetery location of town in Mount Olivet? Ever since the new cemetery's opening, the traditionally white city cemeteries (with the exception of St. John's) had been slowly falling out of favor for burial. The German Reformed Burying Ground would become Memorial Park by the mid 1920's. The Shriver family cemetery plot consisted of Judge Shriver’s children and grandchildren. Along with these, were included two interesting extended family members that served as slaves and servants for this wealthy family. The article mentions both of these individuals, Martha Snowden and Abe Brighton. Martha Snowden, along with her ancient tombstone, was moved into the cemetery on May 11, 1904. Her marble stone reads: “Martha Snowden/faithful colored nurse of children of Edward and Elizabeth Shriver/died 25 Nov. age 28.” The same story holds true for Abe Brighton who died in 1847. His grave marker states: “Abe Brighton/1847 age 60/a faithful servant of the Shriver family”  The Shriver Family Plot in Mount Olivet (Section MM) The Shriver Family Plot in Mount Olivet (Section MM) Sadly, I could not find anything further on these individuals, except for a brief reference in Jacob Engelbrecht’s diary, dated December 5, 1820, in which he recorded a list “of the different Negroes” in Fredericktown.” Engelbrecht simply mentions the “Shriver’s Abraham Brightwell” among his tally. I wonder if the name could have been confused by Engelbrecht—Brightwell instead of Brighton? Or was it possibly changed by the family over time? (NOTE: A Daphne Brighton (d.1893 age 75) can be found among those buried in Greenmount, but there are also multiple burials of Brattons. Two other Brightons are among the burial record of Laboring Sons Memorial Ground—Francis Brighton (b.@1833-d. 1874 age 41) and Harriet Brighton (b. @1814-d.1894 age 80). These individuals can be found in the 1850 census living in the same household with a Margaret Brighton (b. @1830). If Abe’s name was indeed Brightwell, a likely relative named Hannah Brightwell is also in Laboring Sons Memorial Ground. Hannah Brighton died in November 1907 at the age of 100.) The new Shriver lot in Mount Olivet is located in Area MM, placing Martha and Abe within twenty yards of the Johnson family vault holding the remains of Maria Harper. Other nearby friends include Jane Hanson (wife of John) and Dr. Philip Thomas, noted upper class residents and former slaveholders in their own right. Again, these two burials predate Maria Harper by nine years. Maria is the oldest known/earliest born woman of color in Mount Olivet, but Abe Brighton now holds the title for being the oldest known black individual resting here. Interestingly, the names of both Martha Snowden and Abe Brighton could not be found in the cemetery’s database and record books of Mount Olivet. The database is understandable as this system relies on the written record at the time, in this case 1907. Was this done deliberately, to hide the fact that people of color had knowingly been transferred into the cemetery? The white Shrivers can be found on their corresponding lot card for Area MM Lots 22 & 23, but not Martha and Abe. I assure you that I will duly add this info, albeit 110 years later. The Strange Story of a “Stranger” On the flipside of the situation with Martha Snowden and Abe Brighton, our Mount Olivet computer database shows the burial of a “colored” individual on July 24th, 1902. There is scarcely any detail in the official records, however, the information was likely added in recent years based on the finding of an obituary for the deceased. The burial card simply says that a female named Laura Hill was buried in lot 136 within the Stranger’s Row area of the cemetery. Stranger’s Row was a potter’s field area of Mount Olivet, reserved for early visitors to town, unknowns and indigent persons. This was the charity card for the cemetery, a norm in the old days of the funerary business. Dated July 25th (1902), a brief newspaper article mentions the death of Laura Hill, colored, who died at the Montevue Hospital and was buried at Mount Olivet. The actual space of Ms. Hill’s final resting place is lost to time, unmarked and unknown. But we have reason to believe this was no mistake by the paper. We also haven’t found her in other cemetery records.  Montevue Hospital (c. 1909) Montevue Hospital (c. 1909) While we are here, I’d like to explain another burial option of the time that relates to “strangers to town,” tramps, elderly residents and the indigent. The Montevue Hospital was the treatment place of record for Frederick’s black population, even for decades after the establishment of the Frederick City Hospital at the turn of the 20th century. The “hospital building” and later Montevue Home structures replaced the original Frederick Almshouse, where the indigent and insane were housed. Usually, when these full-time residents (black and white) died, they were buried in a “potter’s field” located on the property. Some of those who expired at the Montevue Hospital from sickness, wounds or surgery were buried here as well, but most having means were buried at the city’s established white and black cemeteries including Greenmount and Laboring Sons. The case of Laura Hill is quite puzzling. I’m really not quite sure how, or why, she ended up here in Mount Olivet.  Laura Hill...ultimate fighter? (Frederick News/Aug 3, 1889) Laura Hill...ultimate fighter? (Frederick News/Aug 3, 1889) I found one lone reference to “Laura Hill” in the census records. In 1880, she was listed as an 18-year-old mulatto working as a wash woman, and living on East Third Street, apparently in an apartment. A number of newspaper incidents of the late 1800’s mention Laura Hill. These were generally related to fighting and disturbing the peace. I can’t prove that our Laura Hill was a “rough and tumble” wash-woman, but there certainly is a possibility. No Laura Hill could be found in the 1900 census, but a Martha Hill was the closest match. This 36-year-old woman was living in the infamous tenement complex of Shab Row on East Street, with an 18-year-old daughter named Mary. Martha’s birthdate is listed as January, 1864, and profession given as a cook with daughter Mary as a wash woman. Looking back further, Martha Hill can be found in the 1870 census, but not that of 1880 where I found Laura. Martha in 1870 is shown as the daughter of Henry and Maria Hill. Could these be the same lady? Regardless, it still doesn’t answer the question of how she got to Mount Olivet. The cemetery records fail to show a burial on this date as well. Perhaps this was another stealth burial of a person of color.  Grave of Hester Houston (Area R/Lot 94), "first known black person buried in Mount Olivet" (Nov 20, 1895) Grave of Hester Houston (Area R/Lot 94), "first known black person buried in Mount Olivet" (Nov 20, 1895) "Houston—We have our First Burial" That brings us back to the year 1896, and a definitive first-time burial of a black female, in a documented lot site within the cemetery, and, best of all, capped with a monument. She was Mount Olivet's 6,237th burial on record. But most importantly, the name of this woman, who I believe to be the first black individual buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery, is Hester Houston. I have been familiar with this individual for roughly 25 years, all due to a book entitled The History of Carrollton Manor by William Jarboe Grove. I mentioned Mr. Grove’s magnificent narrative of southern Frederick County in an earlier piece written about Clara McAbee, a young resident of Lime Kiln (near Buckeystown) who was named “Maryland Prettiest Girl” in 1915. William Jarboe Grove was onetime president and treasurer of the M. J. Grove Lime Company. The noted philanthropist grew up on Carrollton Manor and published his memoir laced history book in 1922. On page 48, Mr. Grove speaks of Hester Houston (whom he misnames Easter Houston) a slave once-owned by his aunt Margaret Lauretta Jarboe(1838-1900): “It was not unusual that some respected colored slave was buried beside her master. I will mention one, Easter Houston, who was owned by William Eagle, she was given to his daughter, Lauretta, the wife of Thomas R. Jarboe, who is buried by their side in Mt. Olivet Cemetery.”  Manor House at Gayfield Manor House at Gayfield My curiosity with this woman has been piqued ever since. Hester lived with the Thomas R. Jarboe family on their spacious Gayfield Manor estate at Lime Kiln, having the Monocacy River as its eastern border, and the Buckeystown Pike as a western border. More recently, Gayfield was the 145-acre home of US Congressman Roscoe Bartlett. It was a fine plantation during its heyday, full of social entertaining which surely kept Hester on her toes. That’s all that can be gleaned about Hester Houston in this book, however 19 pages later, Grove tells a story about another one of William Eagle’s slaves with the last name of Houston—perhaps a husband or brother to Hester? Grove writes: “Jonah Houston, who I remember well, large and a powerful man who was looked upon as being the champion fighter in the neighborhood. He was quite an athlete, fond of dancing and fond of liquor, for a drink he would sing and dance the following which usually brought down the house. “This way buzzard and where you ‘gwine crow, I am ‘gwine up the river to jump just so, First upon my heel tap, then upon my toe, Every time I jump around, I jump Jim Crow.” The routine performed by Houston was "Jump Jim Crow", a song-and-dance caricature of blacks originally made famous by white actor Thomas D. Rice in blackface. It first appeared in 1832 and was used to satirize President Andrew Jackson's populist policies. As a result of Rice's fame, "Jim Crow" had become a derogatory expression meaning "Negro” by 1838. When southern legislatures passed laws of racial segregation directed against blacks at the end of the 19th century, these statutes became known as Jim Crow laws. We also know these as the “separate but equal” status of blacks up through 1965, following the monumental Civil Rights movement and legislation passed the previous year. I could not find anything further on Jonah, but in Hester Houston, we have definite proof of a major color boundary “having been jumped.” Hester Houston was buried in the Jarboe family lot in Area R, lot 94. The record book is well over 121 years old and yellowed from age. Mrs. Jarboe met with the cemetery Superintendent (or Secretary) on November 20th, 1895. Hester’s name appears in the log book as the decedent, however there is no notation signifying Houston as being black, mulatto, colored, or Negro. I find this odd, especially for the times, as it seemed common practice to differentiate people of color. As for the public written record, Hester Houston’s obituary/funeral report appears in the Frederick News on November 20, 1895, however it does not mention place of burial. The bulk of the arrangements in those days were handled by the undertaker. Mr. Marshal R. Etchison was that undertaker, and a known friend to the black community. No one from the cemetery would have had a need to open the casket, so they wouldn’t know.  Mount Olivet Superintendent D. J. Michael Mount Olivet Superintendent D. J. Michael I became curious after seeing this allowance of four blacks into the cemetery over a nine-year span between 1895-1904. I checked to see who the cemetery superintendents were during this time and was fascinated to learn that it was only one, Daniel Jerome Michael (1840-1908). Mr. Michael served as the third superintendent of Mount Olivet. It was only a nine-year term which began in 1893 and lasted until late 1907. Michael was forced to resign due to health reasons, and died eight months later. Daniel J. Michael knew two things very well: 1.) the Buckeystown/Carrollton Manor Area of which he grew up; and 2.) the institution of slavery. However, he understood the latter by never being a slaveholder himself, and the same held true with his father Henry S. Michael as far as I can find. The irony lies in the fact that his paternal grandfather and uncles were known slaveholders, as were many of the neighbors that lived around him. Is it possible that he had been raised with abolitionist ideologies?—or simply an admiration for the bond existing between some white families and beloved former slaves and employees of color? Did he, or someone else on the cemetery’s Board of Managers, purposely look the other way, allowing Jim Crow to trip and fall? We’ll never know, but I have a weird hunch that Superintendent Michael may have played a part in these burials, and the surreptitious manner in which each took place, or were recorded. If anything else is telling, Daniel J. Michael’s grave is only 20 yards distant from that of Hester Houston. Stay tuned for next week’s final part 3. It’s a sad story that relates to segregation and Mount Olivet, but offers a positive ending tied indirectly to the Civil Rights Movement. If you have any information, corrections or photographs to add to our stories, we are greatly interested. Please comment or contact me via this website's contact page. Many thanks in advance!  History Shark Productions Presents: "UP FROM THE MEADOWS: The Class" Are you interested in learning more about the incredible African-American heritage story of Frederick City and Frederick County, Maryland? Check out this author's latest, in-person, course offering: Chris Haugh's "Up From the Meadows: The Class" as a 4-part/week course on Tuesday evenings starting March 12th, 2024 (March 12, 19, 26 and April 2). These will take place from 6-8:00pm at Mount Olivet Cemetery's Key Chapel. Cost is $79 (includes all 4 classes). For more info and course registration, click the button below.

3 Comments

Irene Packer-Halsey

3/6/2017 09:20:51 am

Thank you! Your work is amazing! I am learning so much about my beloved Frederick and it's African American legacy...

Reply

Jocelyn Wetzel

3/6/2017 09:46:59 am

Another interesting article, Chris. Keep up the good writing.

Reply

Susan E. Fitzgerald

3/13/2017 08:12:19 am

I can't thank you enough for publishing this blog. I have learned so much about the history of my adopted hometown (I'm originally from Thurmont). I especially commend Mr. Pearcy for his kind consideration in the matter of Bird Smith.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed