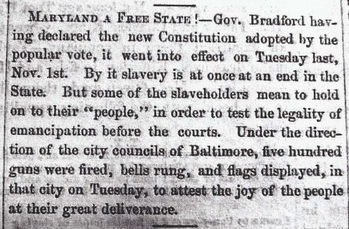

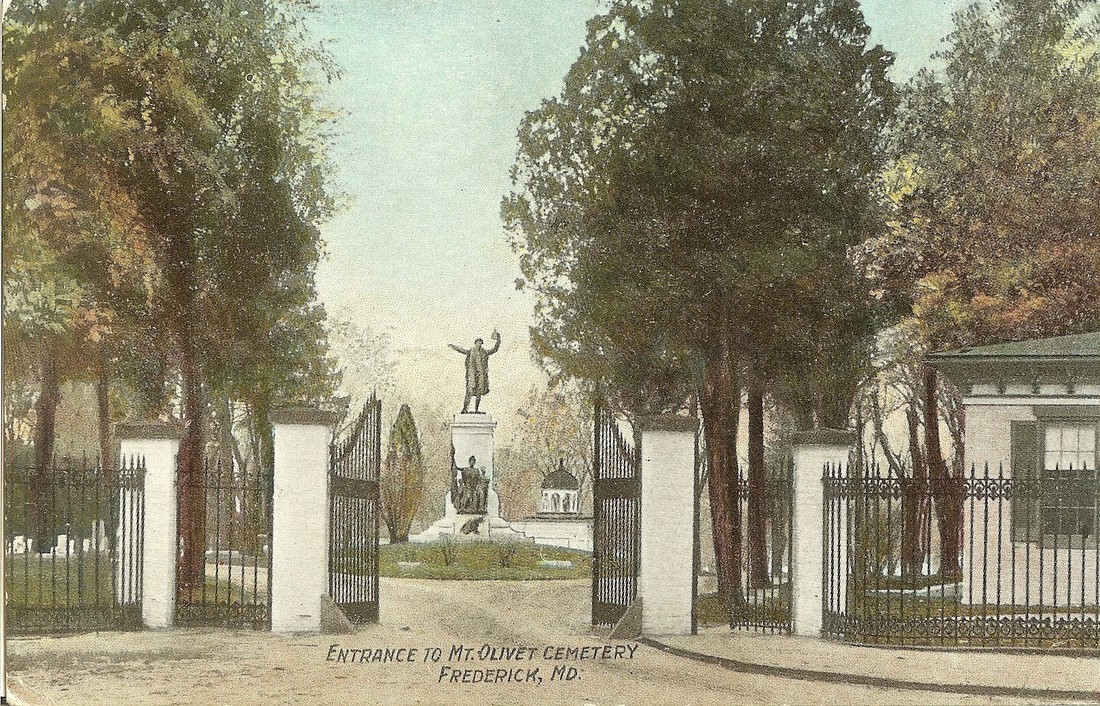

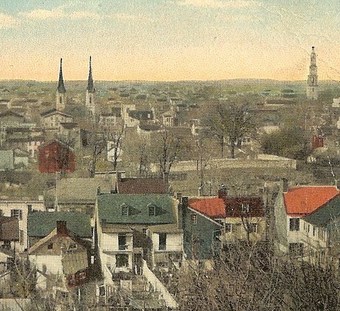

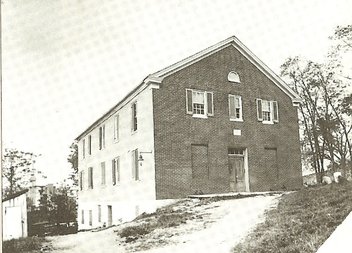

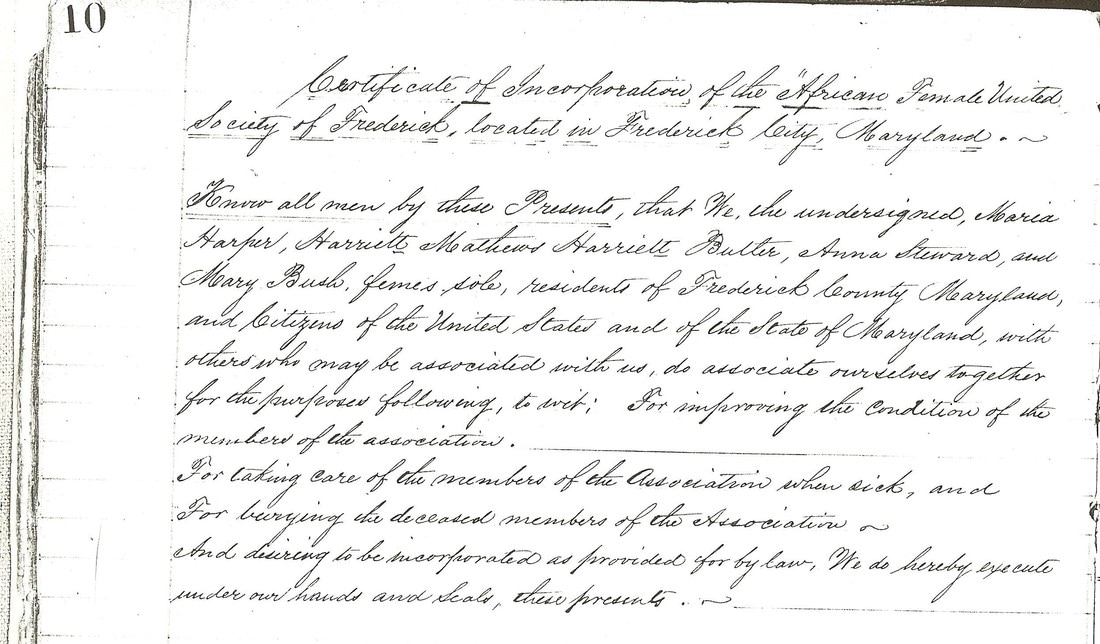

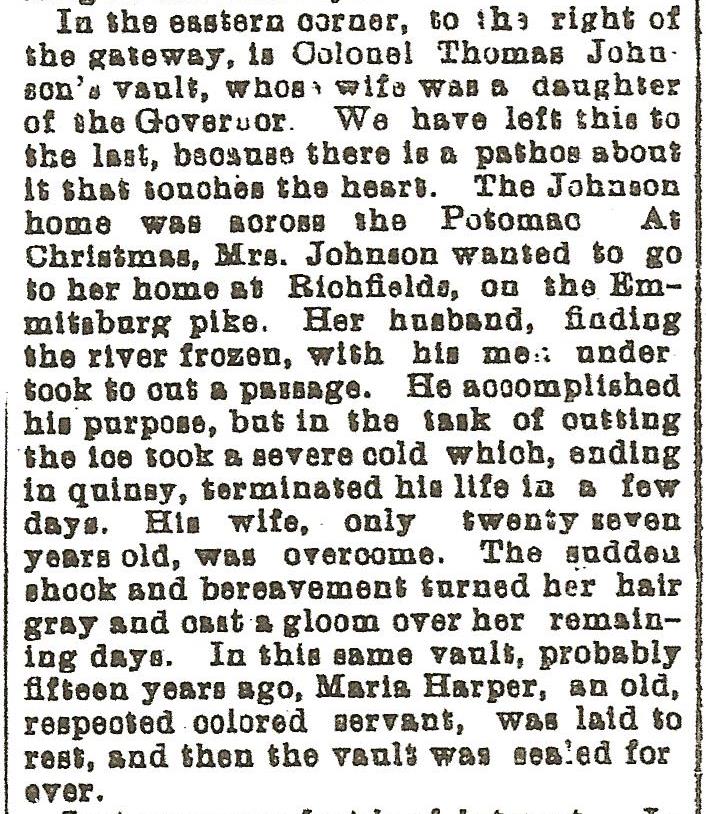

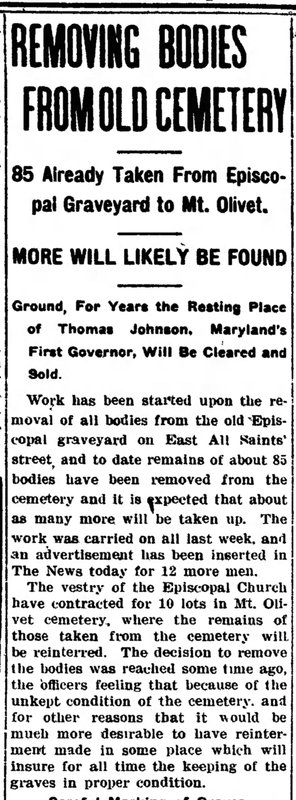

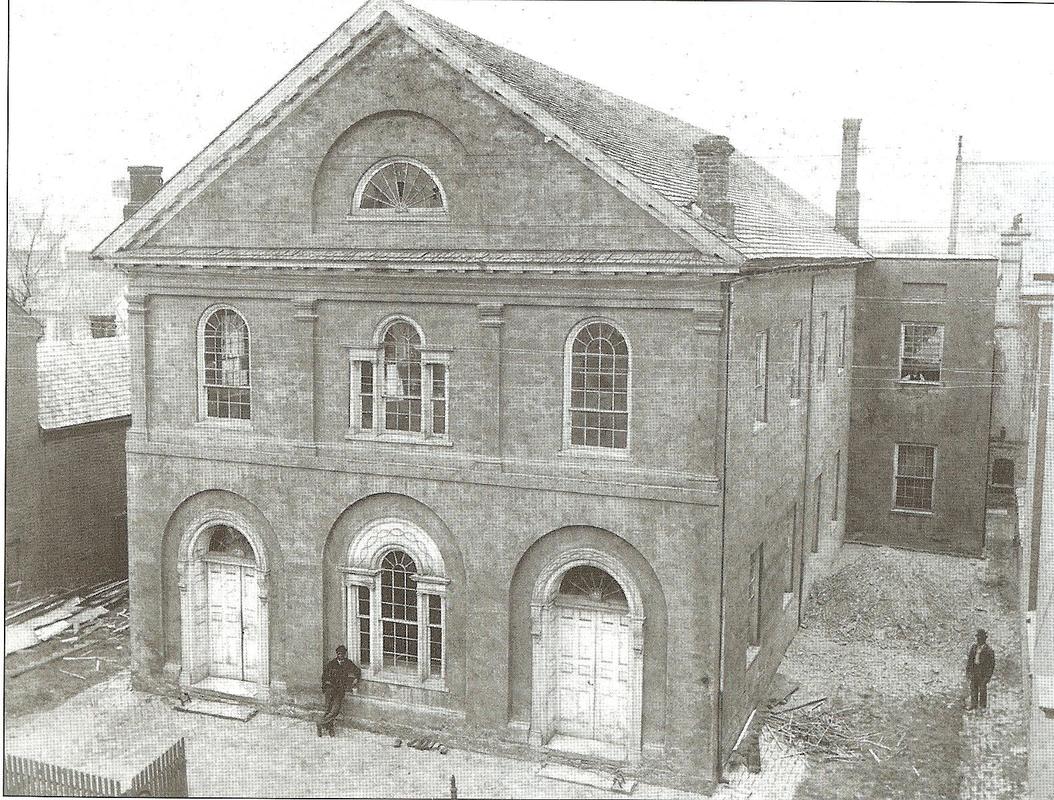

A clipping from the Commonwealth newspaper (Boston, Mass) dated Nov. 5, 1864 A clipping from the Commonwealth newspaper (Boston, Mass) dated Nov. 5, 1864 In honor of both Black History Month and Women’s History Month, I offer a three-part story to bridge February to March. I went in search of the first known burial of a person of color within Mount Olivet. In my research, I came upon three such interesting past residents, all women—and all of whom came into the Mount Olivet Cemetery in unorthodox ways. Of the three, one is the oldest known person of color here. Another was the first to be buried in the cemetery. Finally, the third remaining lady had the most controversial and arduous route ever taken to Mount Olivet, as it would entail a 34-year journey to travel a very short distance. I will share with you the story of one of these ladies this week, and the other two next week. First off, I must provide you with some important context about the times in which these women lived. Mount Olivet Cemetery was dedicated in 1854, ten years prior to the official state sanctioned abolishment of slavery. At this time, the population of Frederick County looked as follows: Total population Slaves/(%) Free Blacks/(%) 1850 40,987 3,913/(10%) 3,243/(7%) 1860 45,591 3,243/(7%) 4,957/(11%) Maryland lawmakers would meet in 1864, with the American Civil War continuing to rage. This was an effort to address, and strengthen, previous principles on how the state was to be governed. Actually, the 1864 Constitution was more so the product of strong Unionists, who had seized control of the state at the time. The document outlawed slavery, disenfranchised Southern sympathizers, and reapportioned the General Assembly based upon the number of white inhabitants. This provision further diminished the power of the small counties where the majority of the state's large former slave population lived. The framers' goal was to reduce the influence of Southern sympathizers, citizens who almost caused the state to secede in 1861. The constitution did emancipate the slaves, but this did not mean equality. The franchise was restricted to white males. Additionally, the Maryland legislature refused to ratify both the 14th Amendment, which conferred citizenship rights on former slaves, and the 15th Amendment, which gave the vote to blacks.  Frederick, county and city, had the unique situation of boasting both free and enslaved blacks living here during the Civil War era. By and large, the northern and north western reaches of the county had fewer instances of slavery due to the original settlement of German peoples in the prior century. These folks generally practiced family operated farms. This was counter-balanced by English/Scots-Irish settlers moving in and settling on the eastern, southern and southwestern areas of the county. Many of these people came from the original 17th century settlements of tidewater/southern Maryland. Slave plantations would take hold in places such as Carrollton Manor, Petersville, Urbana, New Market and Libertytown. As for Frederick City, this was a mixed bag. Household slaves could be found working in small industry and working in homes of wealthy Courthouse Square area English stock families such as the Potts, Murdochs, McPhersons and Tylers. In some instances, upper crust German families can also be found owning slaves. Examples include founding families such as the Getzendanners, Schleys, and Brunners. Even Barbara Fritchie owned slaves—the woman made world famous by the pen of one of the leading abolitionist in the land, John Greenleaf Whittier. The original bylaws and articles of incorporation for Mount Olivet say nothing about excluding burials of blacks within the cemetery. However, there was an unwritten rule of the times here in segregated Frederick. The community, itself, dictated that this not be attempted.  Hosselback Cemetery (Claggett Center, Adamstown) Hosselback Cemetery (Claggett Center, Adamstown) Before emancipation, most slaves were simply buried on the plantations where they lived and labored. Distinct slave cemeteries were prevalent. A surviving burial ground of this kind exists on the grounds of the Claggett Center in Adamstown, just below Buckeystown. Twenty years back, I began my video documentary entitled “Up from the Meadows: A history of Black Americans in Frederick County, Maryland” with video scenes of this humble burying ground, which certainly had more beneath the surface than above. A few field stones were evident, but nothing resembling an official grave marker or tombstones to be found. This is the site of the Hosselboch family cemetery, with provisions for at least two known family-owned slaves. The larger plantation would eventually turn into the Buckingham Industrial School for Boys, a boarding school for white youth, operated by the Baker brothers.  Ceres Bethel AME burying ground near Burkittsville. Ceres Bethel AME burying ground near Burkittsville. A more pronounced “slave cemetery” in Frederick County can be found in north county at Catoctin Furnace, below Thurmont. A roadway project associated with US 15 construction unearthed a cemetery containing nearly 35 souls associated with the iron furnace that began in the colonial era under the ownership of Thomas and James Johnson. Archeological study by the Smithsonian Institute on the remains is ongoing as the managing entity of the project is the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society. There were many other private slave and farm cemeteries across the county, most lost forever to residential and business development. Fortunately, we have several surviving black cemeteries that started to appear in post-emancipation communities and enclaves. These are most commonly located adjacent early rural Black churches such as Hope Hill, Sunnyside, Oldfields, Silver Hill and Ebenezer. Here you will find former slaves buried alongside freedmen. Luckily, community interest and activism has kept many of these burying grounds in satisfactory and respectable condition, especially in the light of longtime burial inactivity and the discontinuation of churches. However, just as many of these need help and protection. As for the smaller towns of the county, separate black cemeteries exist in places such as Middletown, Brunswick, New Market and Libertytown. More times than not, these cemeteries are/were associated with nearby black religious congregations. In other cases, blacks could be found worshipping in traditional white congregations, thus allowing for potential burial in those respective cemeteries. This usually took place in a designated “colored subsection” within a larger cemetery. Examples include Catholic cemeteries such as St. Mary’s in Petersville, St. Anthony’s (atop Catoctin Mountain behind Mount St. Mary’s College in Emmitsburg), St. Timothy’s in Libertytown, St. Joseph’s on Carrollton Manor near Buckeystown, and St. John’s Catholic Cemetery in downtown Frederick.  Amos Tecumseh "Tup" Lucas Amos Tecumseh "Tup" Lucas Back in 1996, an old mentor of mine, Marie Erickson, pointed out to me the grave of Amos ”Tecumseh” Lucas (1848-1917) in Thurmont’s Weller United Brethren, (now United Methodist) Church cemetery. Lucas was well-known by his nickname of “Tup” and served as a tonsorial expert (barber). He practiced his trade in Thurmont for nearly 40 years. The former slave came to town after the Civil War, from Lovettsville in Loudoun County, (VA) with Dr. J.J. Hanshew. He was the only self-proclaimed man of color to live in the Mechanicstown District for nearly 30 years, and serves as an overwhelming minority within the cemetery. "Tup" Lucas was buried in the Hanshew family lot upon his death in 1917. One other black individual, Ms. Helen Hammond, a popular camp counselor on the mountain, would also have Weller UM cemetery as a final resting place in 1977. In Frederick City, four cemeteries were utilized as exclusive burying grounds for black residents. In eras of slavery and segregation, beneficial societies also formed in order to provide burial opportunities for persons of color. The oldest known burying ground for blacks in Frederick City was the All Saints' Church Cemetery, once located on the northern slope of the "Old Hill," between Carroll Creek and East All Saints Street. Today, the Maxwell Place Condominiums occupy the former burial site, and the hill is virtually gone at this site, however can be found again with the creek amphitheater area just to the east. This locale was the original site of the All Saints' Protestant Episcopal Church structure. Many of the leading members of town (along with their slaves) worshipped, and were buried, here. Graves would eventually surround the original church structure. When the All Saints' congregation moved out in the early 1800’s (to locate closer to the Courthouse Square area), a new worship place for blacks and whites was constructed just west of the former location. This became known as the "Old Hill Church.” It sometimes gets confused for the original All Saints' church building, however, that structure was dismantled around 1813 with elements being used for a new home for the All Saint's parishioners on Court Street. Over time, the "Old Hill" congregation eventually came under total black leadership and evolved into Asbury Methodist Episcopal Church (around 1870). Adjacent the church, was a ground lot that contained earlier burials of slaves which had been placed outside the brick-walled All Saints' Cemetery. These dated to the 1700's. When the All Saints' congregation left, free blacks and others began being buried here and around the Old Hill Church structure. By the 1860’s, most burial activity had ceased at the white East All Saints' burying ground. The new Mount Olivet “garden design” Cemetery provided a welcome alternative for All Saints’ white parishioners. Almost immediately, families of means bought lots at Mount Olivet, and had loved ones reinterred—dug up, moved, and reburied. The All Saints' Cemetery started its steady descent, as did other congregational graveyards located downtown. The Old Hill burial situation would also be impacted at this time by the creation of two, new cemeteries, started by local black beneficial groups in the mid to late 1800’s. As for the "Old Hill" church, the Asbury ME congregation purchased land in 1912 at the northwest corner of West All Saint’s and Brewer’s Alley. Here is where they would build their new house of worship (which opened in 1922). In 1913, the All Saints' and Asbury ME trustees put their neighboring properties up for sale, as this was highly coveted real estate. Bodies of the dead had to be moved elsewhere. One such was a former slave and later emancipated woman. Her name was Mrs. Maria Harper. Maria Harper was no stranger to funerals and cemeteries during her lifetime as she was one of the five founding members of the “African Female United Society of Frederick,” known to many as simply "the Mothers." Incorporated in 1868, the aim of this benevolent association was to “take care of the members of the Association when sick, and for burying the deceased members of the Association.”  Furnace Mountain in Loudoun County (VA) as seen from Point of Rocks atop Catoctin Mountain. The Johnson-owned furnace was in this vicinity. Furnace Mountain in Loudoun County (VA) as seen from Point of Rocks atop Catoctin Mountain. The Johnson-owned furnace was in this vicinity. Mrs. Harper’s own burial took place in All Saints' Cemetery on October 3rd, 1884. She had been placed in one of six vaults that resided on the grounds. Her supposed “final resting place” would be the crypt associated with Col. Thomas James Johnson (1777-1815), son of Col. James Johnson of Springfield Manor near Lewistown (and the original furnace master of Catoctin Furnace). This would make Thomas James Johnson the nephew of Frederick’s favorite son, Gov. Thomas Johnson, Jr. Interestingly, our vault owner would also refer to Maryland’s first governor as not only an uncle, but also his father-in-law because he had married TJ’s daughter Rebecca Johnson. Let’s not judge here as this kind of thing happened regularly in those days. Plus it had its benefits such as making family holidays more manageable, not to mention the hassles associated with legal name change, etc.—but I digress. The couple of Col. Thomas James and Rebecca Johnson lived on the Loudoun County shore of the Potomac, operating the Bush Creek Forge, directly across from Point of Rocks. Entitled Ancient “God’s Acre,” a local newspaper article about the All Saints' Cemetery appeared back in November of 1894, and reported Maria Harper’s placement within the Col. Thomas James Johnson vault, after which it was “sealed forever.” (An excerpt of that article appears below) Apparently, forever would be short-lived (pardon my pun), as the tomb would be re-opened in the fall of 1913. At this time, 324 bodies in the All Saints' burying ground were in the process of being removed by the Vestry of All Saints'. They were destined for Mount Olivet, where the All Saints' vestry had purchased multiple lots within Area MM for reburial. Unfortunately, due to earlier vandalism of tombstones, coupled with the problem of missing or incomplete records, only 70 bodies could be properly identified. In addition, individuals placed within family crypts had become co-mingled, in some cases vandals were to blame. As a result, all members of the Johnson family, along with Maria Harper, were re-interred together within a new, large vault at Mount Olivet. This crypt lays underground and directly in front of the large Gov. Thomas Johnson, Jr. monument, and adjacent tombstones of Col. James Johnson and wife Margaret (to the right of the monument). Thankfully a careful documenting of the All Saints' Cemetery was performed by the congregation’s Ernest Helfenstein before the reburial process commenced back in 1913. He was able to record the contents of a number of tombstones, many of which were broken and required Helfenstein to piece together sections in an effort to decipher the information. One of the stones captured at that time belonged to Maria Harper and read as follows: Maria Harper Born Dec 23, 1806 Died Oct 1st, 1884 Aged 77 years 9 months And 8 days Only about 10 headstones were re-erected in Area MM at Mount Olivet along with associated known bodies. Most of the remains were reburied in a mass grave. This mound area lies a few yards beyond the Gov. Thomas Johnson monument. The balance of the tombstones from All Saints' were said to have been buried along with the remains, here. The cemetery apparently objected to the deteriorated condition of these stones, and required them below, and not above, ground—out of public view. Unfortunately, Maria Harper’s monument was one of these.

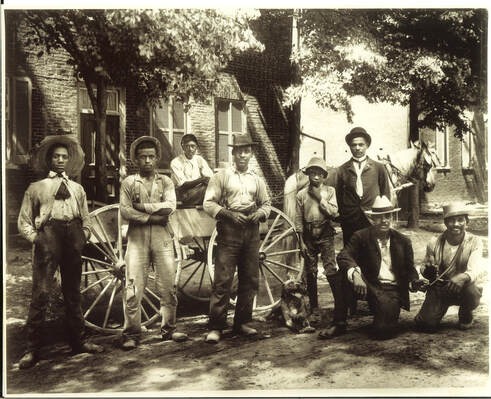

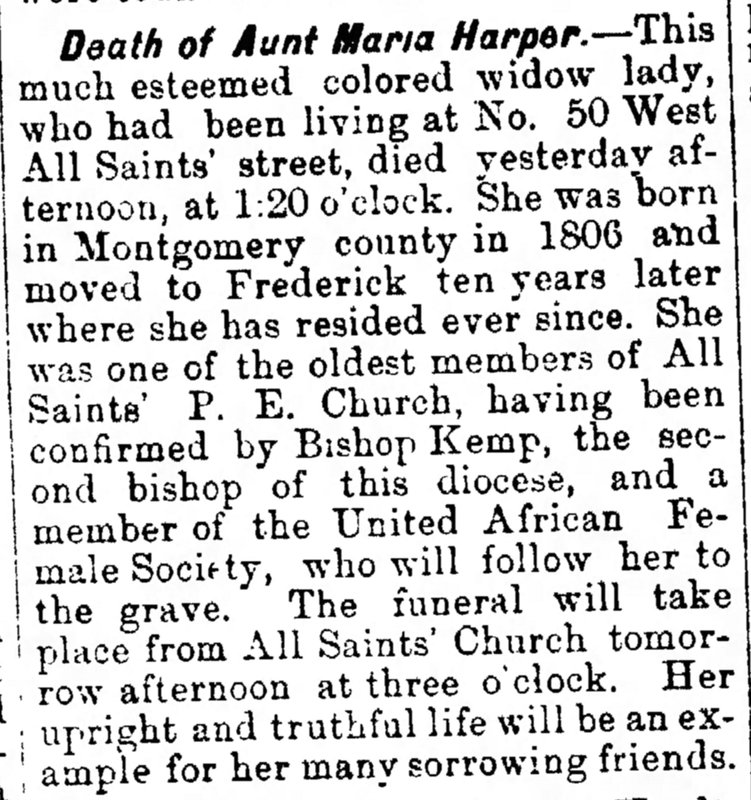

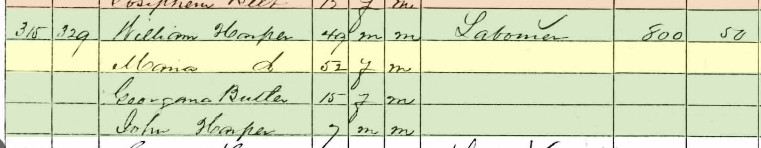

Mrs. Harper’s death was quite noteworthy at the time. Her obituary, and other related articles affectionately refer to her as “Aunt Maria.” At the time of her death, Maria resided at 50 West All Saints Street. She was listed as a “wash woman” in the 1870 census and was noted in her obituary as being one of the oldest members of the All Saints' Protestant Episcopal congregation. It seems that she was beloved by Frederick residents, both black and white.  Anne Grahame (McPherson) Ross (1827-1896) Anne Grahame (McPherson) Ross (1827-1896) The executrix of Mrs. Harper’s estate was Anne Grahame Ross, a luminary from Frederick’s past. Mrs. Ross was the wife of Worthington Ross and lived on Record Street. She had grown up in the Courthouse Square area on adjacent Council Street in the large mansion built by her paternal grandfather, Col. John McPherson. Mrs. Ross’ father, Col. John McPherson II, had married Frances “Fannie” Johnson, granddaughter of Gov. Thomas Johnson, Jr. To come full circle, Fannie’s father was Thomas Jennings Johnson, an older brother to Rebecca Johnson, whom I introduced you to earlier as the wife of Col. Thomas James Johnson—namesake for the funerary vault that Maria Harper was originally buried within. The best I could glean with researching local papers and census records is that Maria was classified as a mulatto, and had married William Harper, three years her junior. This appears in the 1860 census. The All Saints’ archives report this gentleman as Wilson Harper, and records show that the couple was married by Rev. Joshua Peterkin on March 18th, 1847. Within the 1860 census, Maria and William(Wilson) are living in Frederick City with 15-year old Georgeanna Butler and 7-year old son John Harper. By the next census in 1870, Maria appears as a widowed head of household, living with 16-year old son John Harper and 72-year old Alice Fowler. The All Saints' archives show that Maria had been a member of the congregation since 1816, and was actually married twice within the church. She had originally come to Frederick from Montgomery County in the year 1816 as Maria Waters. The ten year-old was a slave, the property of Rebecca Johnson. You may recall that Rebecca’s husband had tragically passed the previous year in 1815, leaving her with three small children. It’s likely that young Maria could have worshipped from the East Gallery of All Saints’ Church's second home, built on Court Street. She also may have participated in the congregations’ “Colored Sabbath School” as well. Maria Waters would marry the first time in February, 1832. Her first husband’s name was Robert Smith, and it is thought that the couple lived in Loudoun County with the Rebecca Johnson family.  McPherson-Ross Mansion (c. 1936) on Frederick's Council Street across from the current-day Frederick City Hall. McPherson-Ross Mansion (c. 1936) on Frederick's Council Street across from the current-day Frederick City Hall. Upon Rebecca Johnson’s death, Maria would return to Frederick in 1837, likely sans Robert Smith, who may have died. I venture to guess that she became the property of the McPherson family, but I have no concrete proof other than the 1840 census shows that the McPhersons had three female slaves living with them at the time, and Maria fits the age range perfectly. Maybe she was brought in to serve as a nanny to Ann Grahame McPherson, who would have been 10-years old in 1837? Maria remarried in 1847, as Miss McPherson turned 20. Was husband William(Wilson) Harper a slave of the McPhersons as well? I bring this up only due to the existence of a female slave named Ruthie Harper in the McPherson family. (She was written about by legendary Underground Railroad conductor William Still, having escaped slavery and Mr. McPherson in 1858. ) Anne Grahame McPherson would marry Worthington Ross in January, 1850. I assume Maria must have had an equally strong relationship with Anne’s aunt, Rebecca Johnson. This all can explain the indelible bond between these women, with major differences reflected by age and race. It would also give credence to the “Aunt Maria” moniker, not to mention the tremendous clout needed to have a former slave buried within the white All Saints' Cemetery and the prominent Johnson family crypt of her former owner. And to think, for over the past 100 years, Maria's remains reside alongside Gov. Thomas Johnson, Jr. within the same vault. Whatever the case, I pronounce that Maria Waters Harper is most likely the oldest/earliest born black resident of Mount Olivet Cemetery—but I need to caution that she wasn’t the first.  History Shark Productions Presents: "UP FROM THE MEADOWS: The Class" Are you interested in learning more about the incredible African-American heritage story of Frederick City and Frederick County, Maryland? Check out this author's latest, in-person, course offering: Chris Haugh's "Up From the Meadows: The Class" as a 4-part/week course on Tuesday evenings starting March 12th, 2024 (March 12, 19, 26 and April 2). These will take place from 6-8:00pm at Mount Olivet Cemetery's Key Chapel. Cost is $79 (includes all 4 classes). For more info and course registration, click the button below!

4 Comments

Jim Rowe

2/27/2017 12:52:16 am

Love your story . So interesting. Looking forward to the next one . Thanks !!

Reply

2/28/2017 08:59:06 am

Chris, love the stories; you are doing a wonderful job with this.

Reply

Cary Wider

3/1/2017 09:03:08 pm

This is an enormous resource, thank you for all the hard work and we look forward to you next report.

Reply

Beverly Ford

4/7/2018 03:12:17 pm

Despite having been born and raised in Frederick County of a long line of black ancestors, your stories are the most extensive of any I’ve come across in my seventy-seven years. I own a copy of your “Up From the Meadow” but these stories strike me as older and much more personal. Just recently I’ve wondered about resources available to construct a scenario of life for blacks in the county, e.g., personal diaries and letters. I hope to be able to have a conversation with you at your convenience.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed