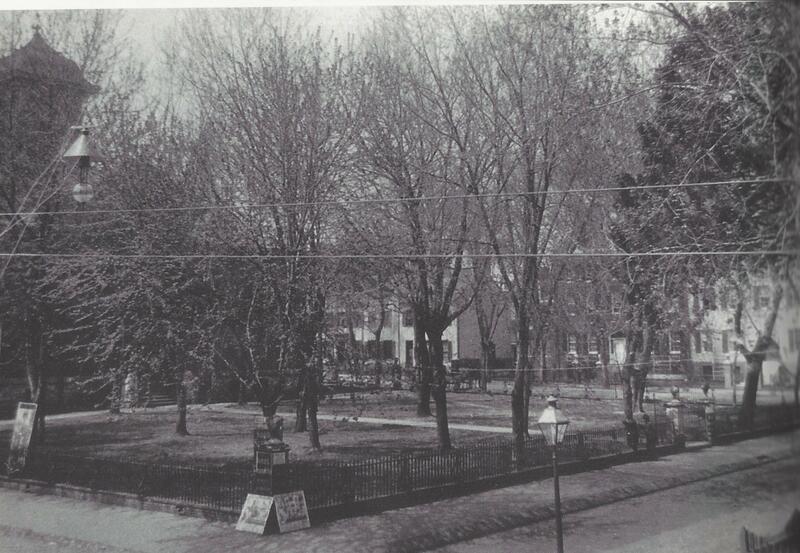

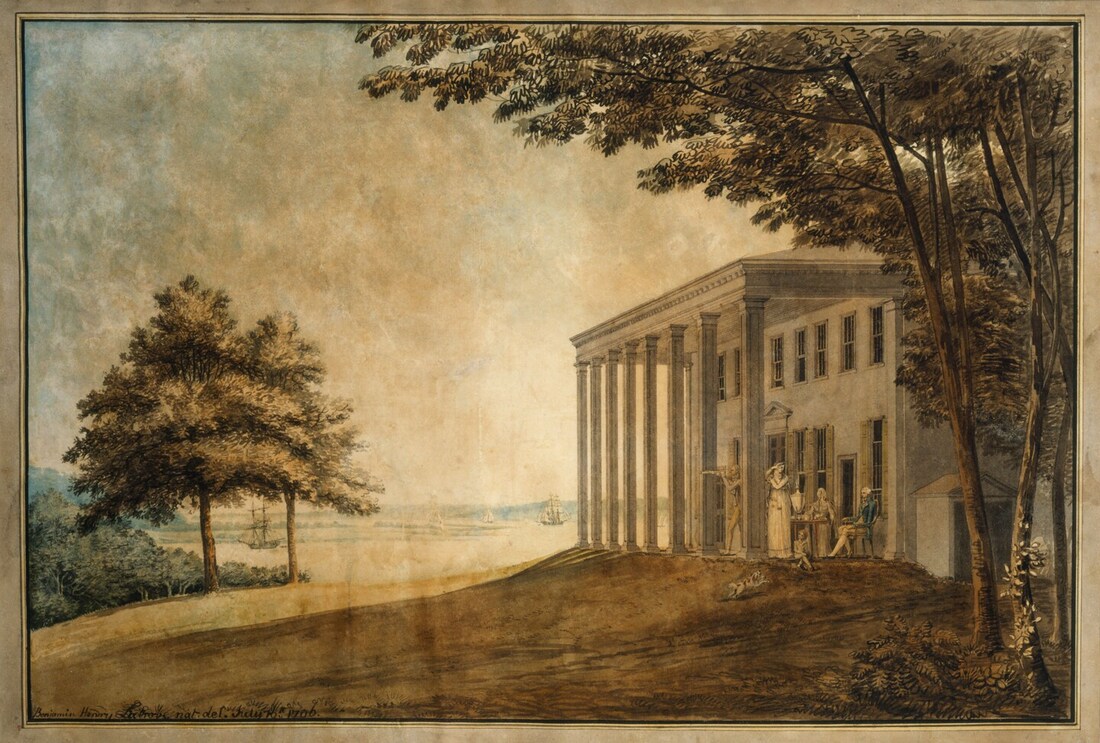

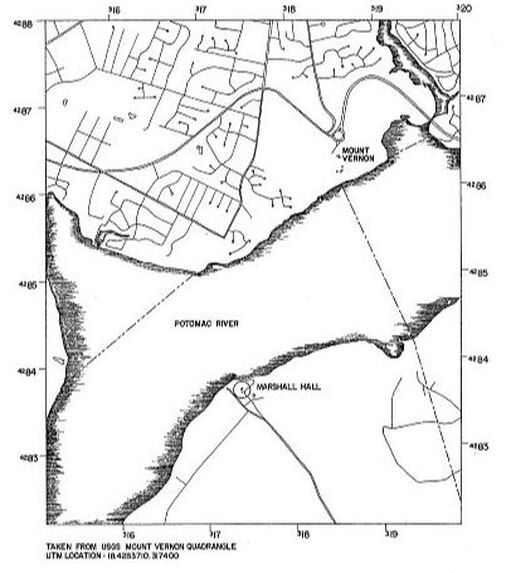

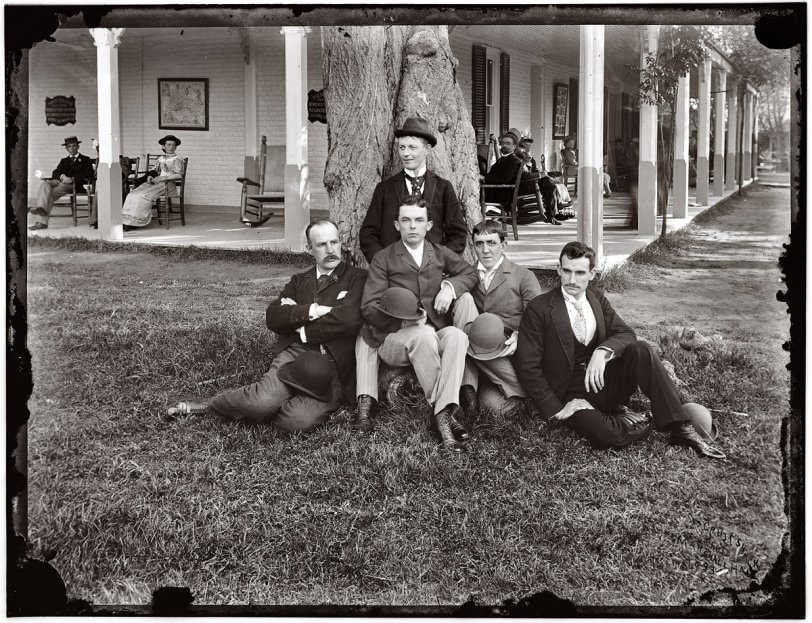

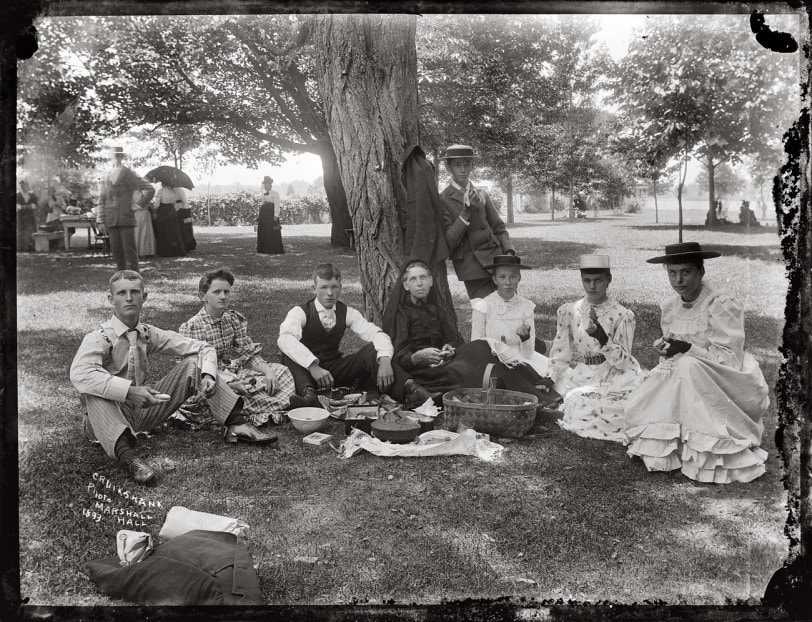

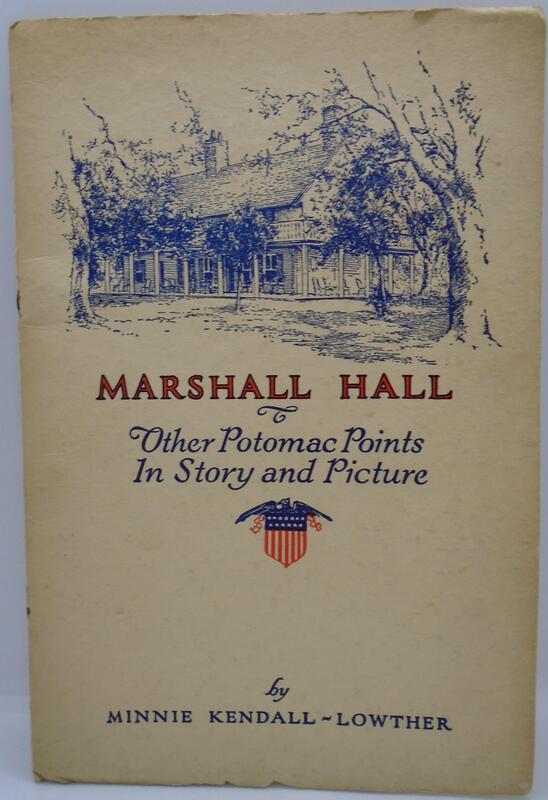

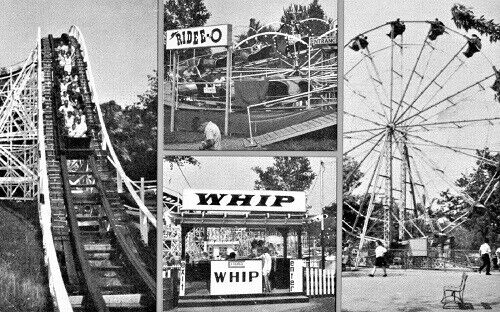

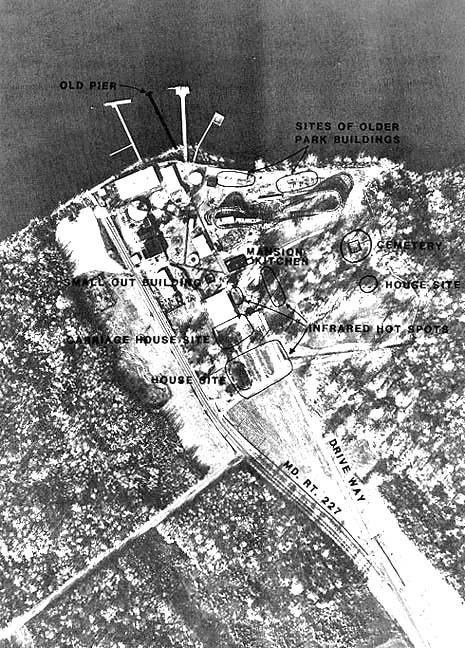

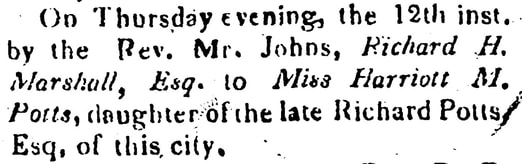

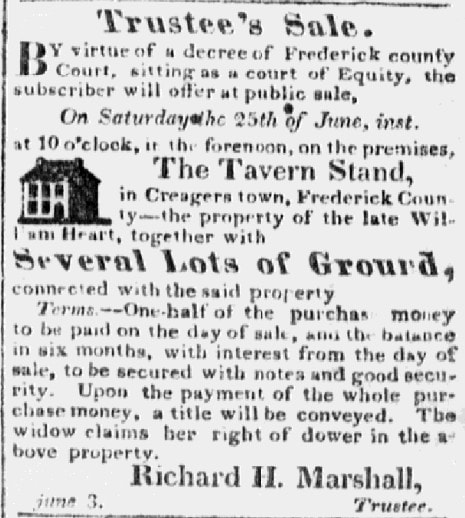

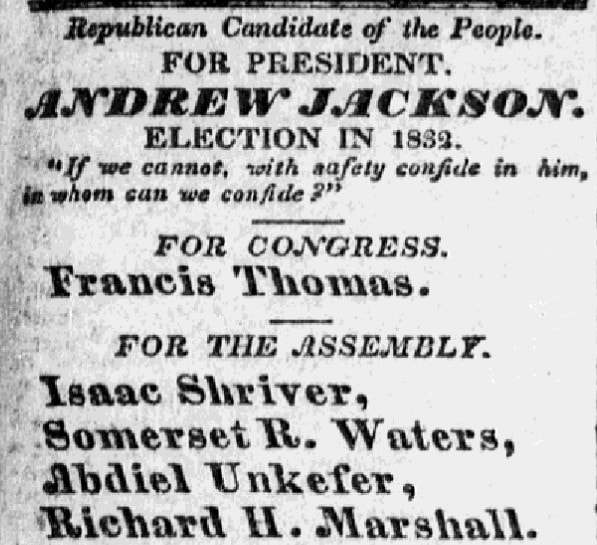

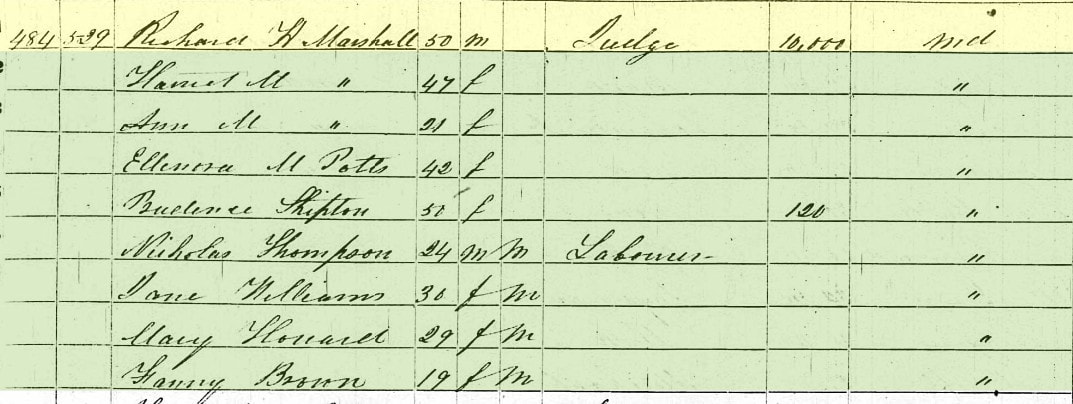

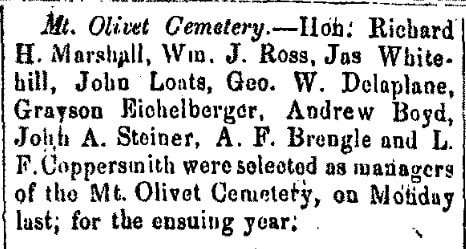

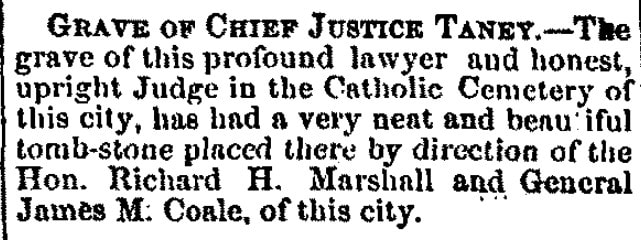

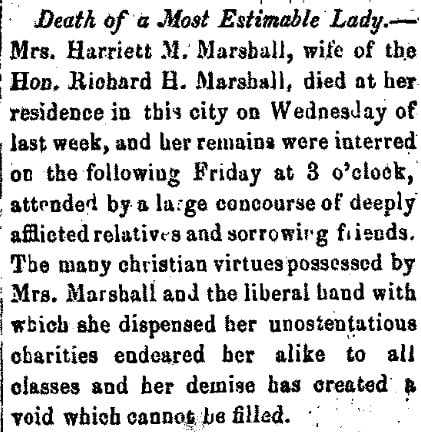

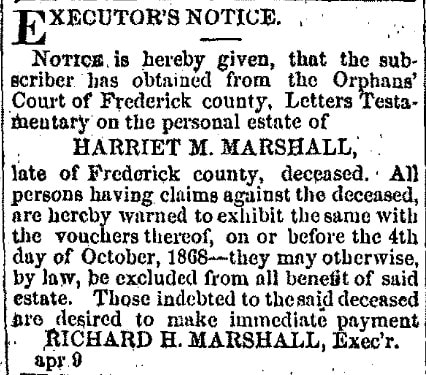

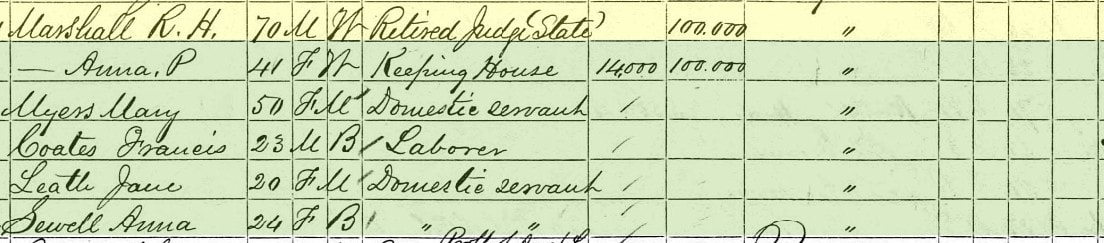

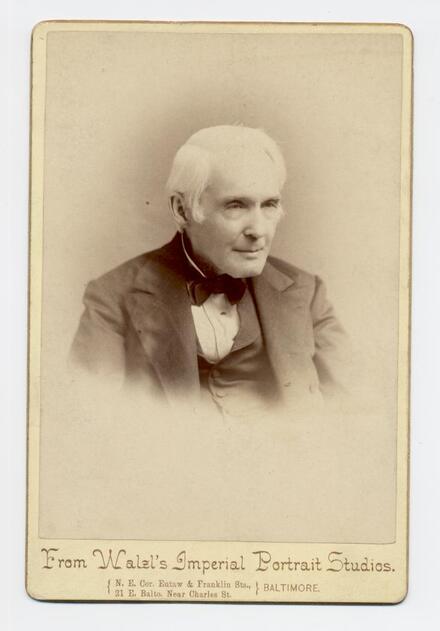

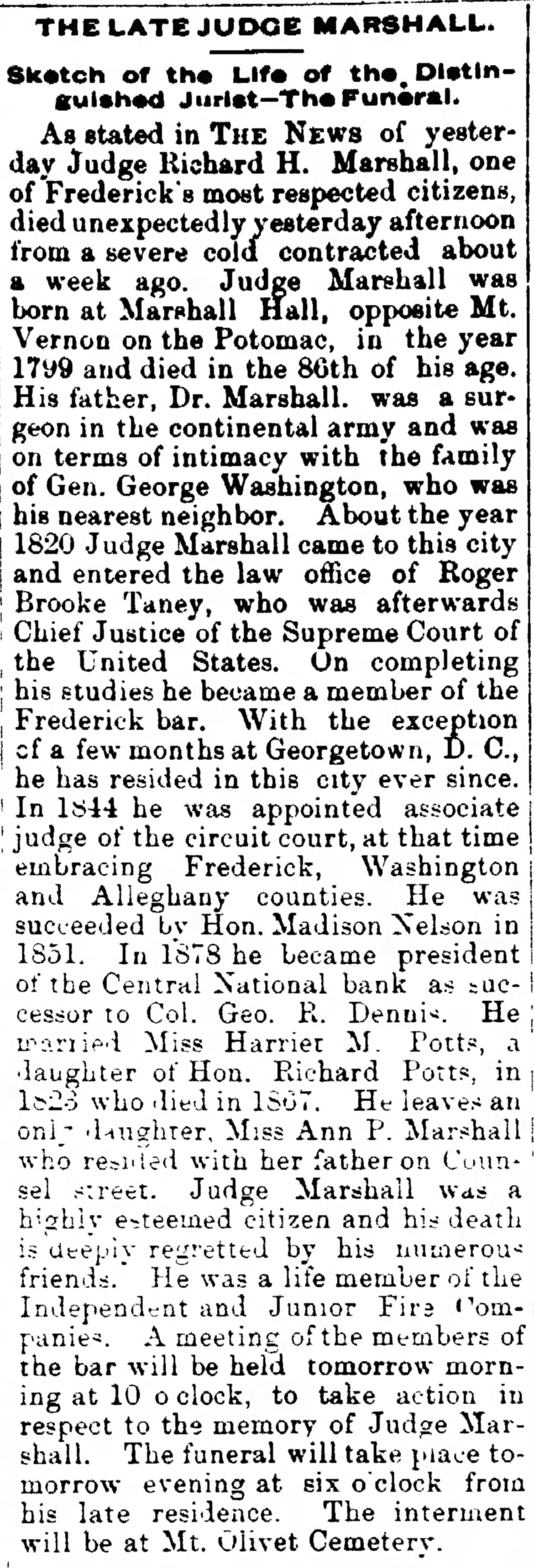

While conducting walking tours, I usually joke with visitors that the Potts Lot in Area G is Mount Olivet’s only “gated community.” This is an area on the northeastern approach of Cemetery Hill that includes a large, multi-plot collection of a few of Frederick’s most prominent families—primarily hailing from the Courthouse Square neighborhood of Frederick. The Potts Lot is surrounded with decorative, iron railing—a delineation barrier that dates from the cemetery’s earliest days in the 1850s, when it was not uncommon to see many family lots “fenced-in” so to speak. The practice was both practical and decorative. Iron railings and fences, complete with closeable gates like the one here at the Potts Lot, started with a simple purpose in mind—keeping unwanted animals out. We are not just talking simply about woodland creatures here, but more also cattle, pigs, sheep and large wild animals. As far as cemeteries are concerned, fencing has also served as a sign of respect to buried loved ones and added a degree of attractiveness and panache to family lots. This practice was also accomplished by the construction of stone and brick walls around church yards and cemeteries. Based on the early burials (and reburials) found within the Potts lot, it’s not hard to see that the graves here date primarily from the early to mid-1800s. The surrounding fence is authentic and shows the talent and work of craftsmen of a time before pre-fabricated shapes and mouldings. The Potts Lot fence is hand-hammered with evident grooves and dents. No one is quite sure when this fencing was added, but it is thought that it was done within the first few years of the cemetery which opened in spring of 1854. I once had a brief conversation about the fence with my friend, Elizabeth Comer, longtime professional archaeologist and president of the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society. We both agree that there is an possibility that this particular railing could have been forged at the Catoctin Furnace due to connections to this Potts family of decedents, and relatives of another that has been forgotten here to time—the Marshall family. Liz and I promised one day to make a study of the Potts Lot's fencing to see if it matches other known exports of Catoctin Furnace. One particular example of fencing from Frederick history seems like a good starting point to this exercise. I’m talking about Courthouse Square, a place where many of the decedents buried here in the Potts Lot once resided. As a matter of fact, I broached the subject exactly five years ago back in March 2019 when I wrote a story about Gen. James C. Clarke, a transportation captain of industry and namesake of Frederick’s Clarke Place who helped add to the beauty of our town’s Courthouse Square. Frederick became incorporated as a city in 1817 by an act of the state assembly. Prompted by animals grazing on the courthouse lawn, an ordinance issued that same year ordered that all hogs and geese found wandering in the streets be impounded. Notice of their arrest was made by public outcry at the Market. To prevent animals from using the courtyard as a pasture, residents and officials decided to enclose the Courthouse grounds with iron railings and ornamental iron gates much like a London square. Authorities were stunned by the expense of the proposed project, however a leading citizen and neighbor in Col. John McPherson agreed to donate the railings. Beginning in 1818, Courthouse Square resident, Col. John McPherson began installing iron railings around the Frederick County Courthouse and subsequent public lawn. This material was forged at McPherson’s Catoctin Furnace operation located in the north sector of the county between Lewistown and Mechanicstown, destined to become Thurmont. Apparently, the neighbors of “the Square,” consisting of the town’s “upper crust,” were annoyed with the recent phenomena of rogue animals grazing on the prestigious courthouse lawn that once boasted legal luminaries such as Francis Scott Key, Roger Brooke Taney and Reverdy Johnson. What seemed like a philanthropic venture by McPherson soon angered the general citizenry as they saw this “fencing” symbolizing an obtrusive wall to a public place and access to courthouse amenities and officials. It also seemed an extension of the adjacent affluent neighbors hoping to keep all others out of their prestigious neighborhood unless they had official court business to perform. The squabble would last for many decades. Seventy years later, the railings were finally removed in 1888. To help pacify the masses, Gen. James C. Clarke found it necessary to offer an olive branch to all citizens by providing a perfect centerpiece to the courthouse green—an ornamental fountain. The Clarke fountain was duly dedicated to all people of Frederick. That’s all well and good, but doesn’t exactly connect dots to Mount Olivet and our Potts Lot. Or does it?There are several unique connections among this cemetery, the Potts Lot and the history of Catoctin Furnace. It has more to do with former residents and entrepreneurs than the actual manufacture of iron. Outside of the Potts Lot, one can find the graves of the Fitzhugh girls about 30 yards to the north. These were daughters of one-time Catoctin Furnace owner Perigrine Fitzhugh who later moved to California. In Area H/Lot 416 sits the gravestone of Isabella Hudson (Fitzhugh) Perryman (1844-1864) and three sisters: Amy, Amelia and Henrietta Fitzhugh. Isabella was the namesake for the existing iconic second stack structure of the once booming pig-iron furnace operation. I wrote a "Story in Stone" about this family of Fitzhughs in October, 2017. To the east, about 20 yards from the Potts Lot, we have the graves of the fore-mentioned Col. John M. McPherson (1760-1829) and his son in law John Brien (1766-1834). These two gentlemen were partners in ownership of Catoctin Furnace in the early 19th century (before the Fitzhughs), and were also next door neighbors in “Court Square.” For it was these gentlemen who built impressive twin mansions at 103 and 105 Counsel Street, now spelled Council Street. These structures date to 1817, and Col. McPherson is best remembered for his role in helping to bring the Marquis de Lafayette to town in late 1824. The French hero of the American Revolution was wined and dined by Col. McPherson, himself, at that time in the home that still stands today. Today these homes are known by the names of later owners as the Ross and Mathias mansions. A mother and daughter tandem, part of the same local Mathias family that produced Sen. (and noted statesman) Charles McCurdy “Mac” Mathias, are the current residents. The elder Theresa Mathias Michel owns the house formerly owned by her parents (Charles McCurdy Mathias, Sr. and Theresa McElfresh Mathias) and grandparents (Charles B. and Grace Trail). Daughter Tee Michel owns the former Ross Mansion next door. However, this house (originally known as the McPherson Mansion) could also go by the name of the Potts Mansion, or Marshall Mansion as it did during other ownerships. I’ve had the good fortune to dine within and explore the interiors and gardens of both houses over the years. To do this though, I had to gain entry through the heavy wrought iron front gates that are reminiscent of those found in places like Charleston, South Carolina and New Orleans. Since the original builders of these houses owned the furnace, it’s no wonder how they got here. The iron railing in front of these homes on Council Street also provides a tangible example of the quality of the former fence that once surrounded Court Square. To think that Gen. Lafayette gained entry to the Ross/McPherson home by use of this same front entryway. Another individual of major patriotic fame to do so was more of a frequent visitor to the Ross Mansion in the early 19th century—Francis Scott Key. Key’s supposed law office was a stone’s throw away on North Court Street. The “Star-Spangled Banner” author regularly looked in on his first cousin, Eleanor Murdoch Potts (1773-1842), who resided here in the house after McPherson’s ownership. Eleanor Potts is one of 42 family members holding that surname and buried within Mount Olivet’s Potts’ Lot. She and husband Judge Richard Potts (1753-1808) are more than worthy of having their own “Story in Stone” written, which I will surely do on another day. Eleanor and Judge Potts died long before the opening of Mount Olivet, and originally reposed at the All Saints’ Protestant Episcopal burying ground along Carroll Creek. Our records don’t specifically say the exact date, but it is safe to assume that they were among the first two individuals placed in the Potts Lot around the time of Mount Olivet’s opening.  Upon closer inspection of the entrance of the Ross home, one will notice a polished, brass “doorbell pull” at the top of the front door landing. Etched directly below this entry accoutrement is the name “R. H. Marshall.” "Who is this gentleman, you may ask?" Well, his full name is Richard Henry Marshall, and he would be the one I’d love to have had the opportunity to ask about the Potts Lot fence here in Mount Olivet. Mr. Marshall, a lawyer, was not only one of our original cemetery founders, but was a member of Mount Olivet's first Board of Directors from 1852-1865. In looking at old "minute books," I saw that Richard Marshall actually proposed the location for the superintendent’s house to be built in the northeast corner of the property and directly adjacent the entrance off South Market Street. It was also Mr. Marshall who is responsible for establishing this large, fenced plot area known as the Potts Lot, in which he would have re-interred his wife Hariett's family members from All Saints’ Protestant Episcopal Cemetery. I soon learned that Richard H. Marshall purchased lots in which to move Francis Scott Key’s parents (John Ross and Ann Phoebe Key) and the Taneys including Ann (Key) Taney (1783-1851) and daughter Alice on behalf of his old friend and legal studies mentor, Roger Brooke Taney. They occupy the Potts Lot as does another interesting individual Marshall moved from All Saints’ by the name of Arthur Shaaf. Mr. Shaaf was a cousin of Francis Scott Key and local lawyer who served as a mentor to both Key and Taney. The Marshalls actually have the largest grave monument within the Potts Lot. I also have noted that the surname can be found upon the fore-mentioned Potts Lot fencing. So, this is why I have always wondered why this area is not referred to as the Marshall Lot? My question was answered when I found that Richard Marshall married Miss Harriet Murdoch Potts, a daughter of Hon. Richard Potts and wife Eleanor, in 1823. Mrs. Marshall died in 1867, just 13 years after the cemetery opened. In conversations with a few friends of mine with a commanding knowledge of Court Square lore and history, I learned that Mr. Marshall certainly helped his own standing, both professional and personal, by marrying into one of Frederick’s wealthiest and most respected families. This led to his eventual place of residence becoming the later known Ross mansion on Council Street, originally built by Col. John McPherson and once the home to Marshall’s in-laws—Richard and Eleanor Potts. So, just who was this Mr. Marshall? Richard Henry Marshall Richard Henry Marshall was born March 8th, 1799 at Marshall Hall, a former plantation located diagonally south and across the Potomac River from George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Marshall Hall is near Bryans Road in Charles County, and sits on the majestic banks of the lower Potomac River. I had the opportunity to visit this place last June after my son’s participation in a nearby baseball tournament. It was certainly worth the look. Although only ruins remain today, it's not too hard to imagine that Richard H. Marshall’s upbringing here was “not too shabby” to say the least. Multiple generations are contained within a “Marshall Lot” here on the old grounds within a fenced-in burial space. This includes Richard H. Marshall’s parents, Dr. Thomas Marshall II (1757-1829) and Anne Claggett Marshall (1778-1805). In this private family plot are Richard’s two brothers in Thomas Hanson Marshall (1796-1843) and George Dent Marshall (1802-1820); and grandparents Capt. Thomas Hanson Marshall I (1731-1801) and wife Rebecca Hanson Dent Marshall (1737-1770). For good measure, one will also find our subject’s great-grandparents here as well: Thomas Marshall I (1694-1759)and Elizabeth Bishop Marshall (1693-1750), first owners of Marshall Hall. With his whole family tree within one family lot, it’s not hard to imagine why Richard saw the importance in keeping the Potts family of his wife together, along with having a place for his own offspring to be buried with himself and his spouse. In its heyday, the Marshall family retreat was a classic colonial-era mansion, and what remains of it is now part of Piscataway Park operated by the National Park Service. The home is said to have been “one of the finest built on the Maryland shore of the Potomac in the early 18th century” as the Marshall family were minor gentry and owned as many as 80 slaves by the early 19th century. Marshall Hall, patented as “Mistake” in 1728 by Thomas Marshall, was the home to this family from sometime after 1728 until 1857. The mansion house dates from the earliest period and was erected as a one and one-half story brick house and enlarged c. 1760. Soon after the Civil War, the site became a highly frequented picnic ground because of its proximity to Mount Vernon. Steamship lines, originally established to ferry tourists from Washington DC and Alexandria to/from Mount Vernon, discovered a new source of revenue in the park across from the historic estate. In the 1880s, the Mount Vernon and Marshall Hall Steamboat Company ran large ships between Washington, Alexandria, Mount Vernon and Marshall Hall: the round-trip fare at that time was $1, and included admission to Mount Vernon. Washingtonians fled the summer heat of the city for all sorts of events at the picnic grounds, from exclusive catered events to popular cultural events such as a swimming exhibition given by the daredevil Robert Emmet Odlum in the summer of 1878, seven years before his death at the Brooklyn Bridge. Marshall Hall later became one of the first amusement parks in the Washington, DC area in the 1890s, offering numerous "appliances of entertainment" for visitors who wanted to do more than picnic, many of them arriving by river boat. Starting in the 1870s, annual jousting tournaments took place at the site. In the last century, the site of Richard H. Marshall’s childhood home and family estate was known as a small amusement park opened in the early 1920s, and included a small wooden roller coaster. It was a favorite of Washington, DC residents who continued to arrive via an excursion boat. New attractions were added throughout the 20th century, and gambling became a major draw for a while after World War II. Between 1949 and 1968, the Southern Maryland area offered the only legal slot machines in the United States outside of Nevada. A larger wooden roller coaster was built in 1950, but would be destroyed by tornado force winds in July 1977. This was the beginning of the end for the amusement park which officially closed in 1980. The National Park Service gained control of the park after Congress, acting upon a request from the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association, mandated that the views from Mt. Vernon had to be protected and returned to something resembling the days when George Washington sat on his colonnaded porch and looked across the Potomac. The term "historic viewshed" was coined for this act of preservation and the Park Service tore down all vestiges of the amusement park in 1980, whose popularity had declined due to competition by much larger, newer parks. A fire destroyed much of the colonial house soon after in 1981. In January 2003, a truck driver slammed his rig through the remaining hulk. The damage done to the brick shell was repaired the following year. Getting back to Richard H. Marshall, he was the son of Dr. Thomas Hanson Marshall I, a surgeon in the continental army during the American Revolution. He is said to have been “on terms of intimacy with the family of Gen. George Washington, who was his nearest neighbor.” I couldn't find anything on Richard Marshall's childhood, but I'm sure he was provided with an education which would prepare him for the study of law, and the mentoring he received from Roger Brooke Taney in Frederick around the year 1820. On completing his studies, he became a member of the Frederick bar. With the exception of a few months at Georgetown, DC, he would reside in our fair city. As stated earlier, he married Harriet Potts on June 12th, 1823. The couple would have multiple children, however only one lived to maturity in Miss Ann Potts Marshall (1827-1890). The others included Eleanor Ann Marshall (1824-1827), Harriet Potts Marshall (1826-1826) and Mary Elizabeth Marshall (1831-1833). The family resided at 101 Council Street. Mr. Marshall certainly involved himself in town activities including delivering a patriotic address on July 4th, 1825 in conjunction with a parade culminating in a public celebration held at the Frederick Courthouse. In 1844 Marshall was appointed associate judge of the circuit court, at that time embracing Frederick, Washington and Allegany counties. He was succeeded by Hon. Madison Nelson in 1851. In 1878, he became president of the Central National Bank as successor to Col. George R. Dennis. Judge Marshall appears in the early newspapers quite often in conjunction with legal handlings, trustee sales and the many boards he served on. Harriet Marshall died a week before Christmas in 1867. This too would cause his name to appear in our local weekly papers, including an executor's notice which was rare to see for a woman at this period of history, but not in Mrs. Marshall's case. Richard H. Marshall died on September 3rd, 1884 at the age of 85. He would be laid to rest next to his wife who had predeceased him nearly 17 years earlier. Here, Marshall had erected a large monument to her memory. A few yards behind this grave marker, one can find three small monuments marking the reburials of the couples young children who died in the 1830s and were originally buried in the All Saints’ burying ground. The last member of the immediate Marshall family here in Frederick died in 1890 at the age of 62. This was only six years after her father's death. Ann Potts Marshall never married and the surname of this mighty Maryland family ceased with her. This, more than anything else, explains why the Potts name has stuck to this unique gated lot within Mount Olivet’s Area G.

Richard H. Marshall's grave lot in Mount Olivet, and former home in Frederick, don't carry his family name, but there exist subtle reminders, etched and forged, in metal. At least an old rollercoaster and amusement park once carried the mighty name of Richard's prominent colonial family—but that too is slowly becoming a faded memory of yesteryear.

1 Comment

4/10/2024 12:20:21 pm

We can also glean so much from the response and conduct of friends and families of the deceased themselves. Any opportunity to witness and/or practice resiliency can be a sacred experience.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed