|

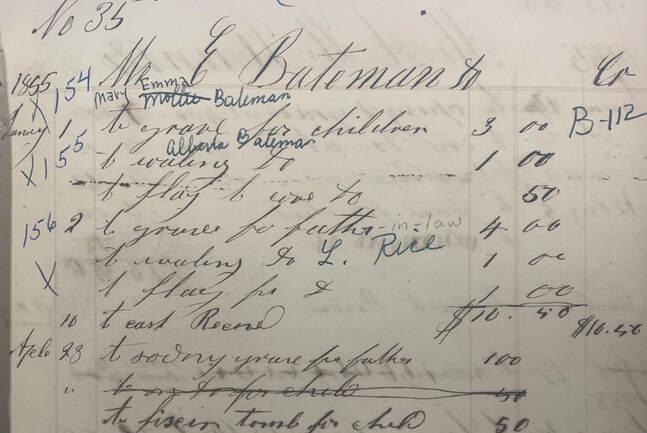

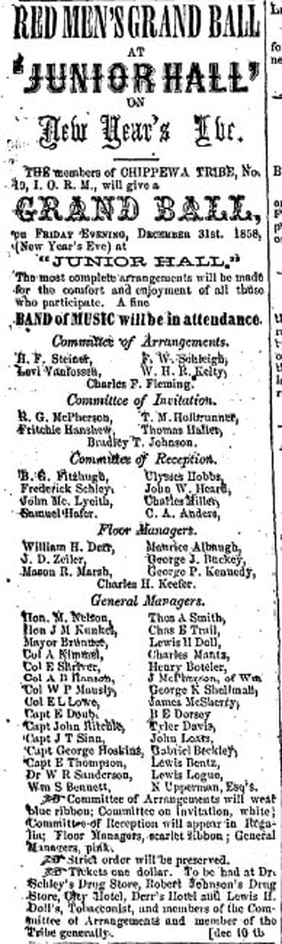

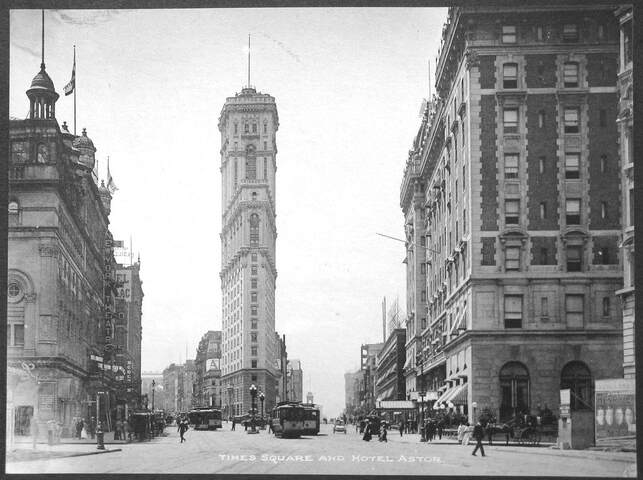

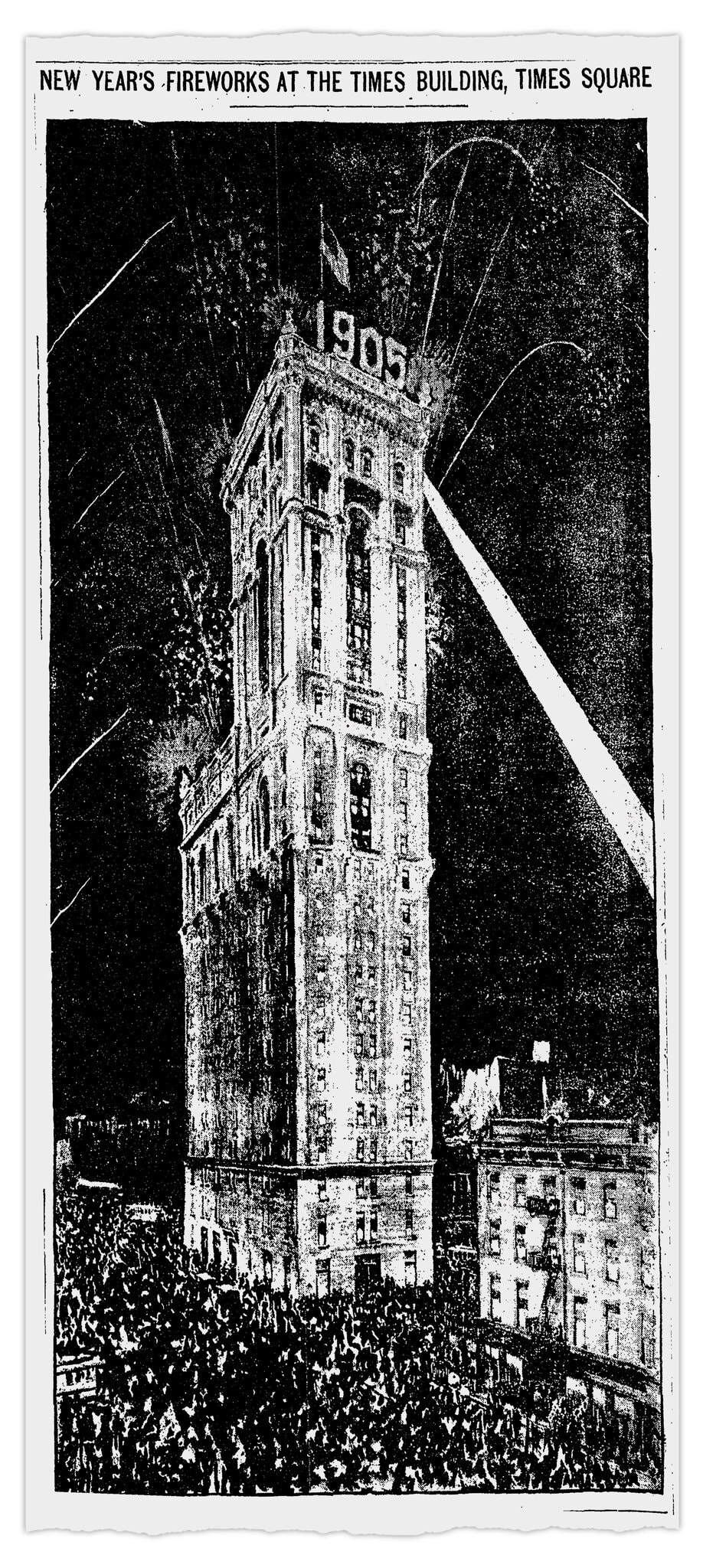

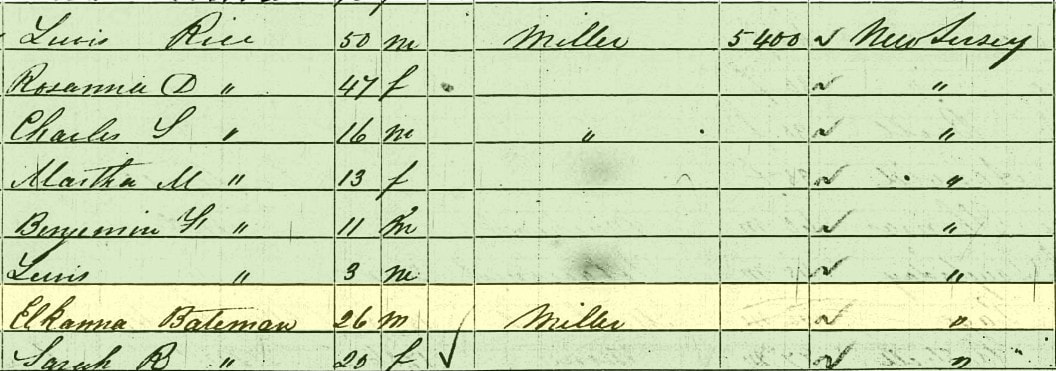

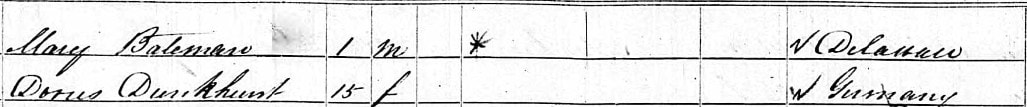

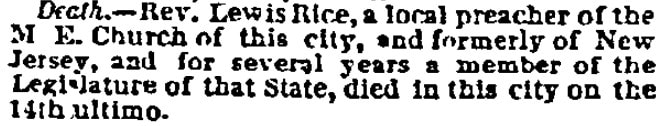

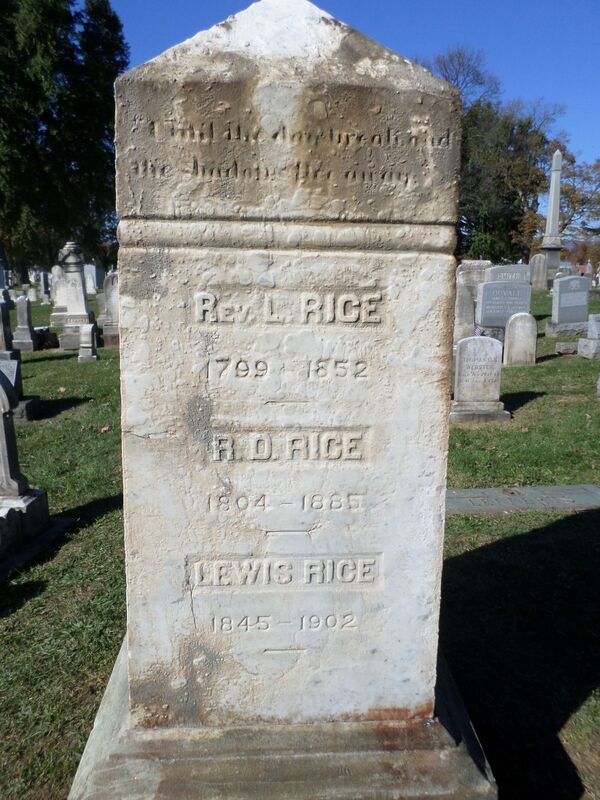

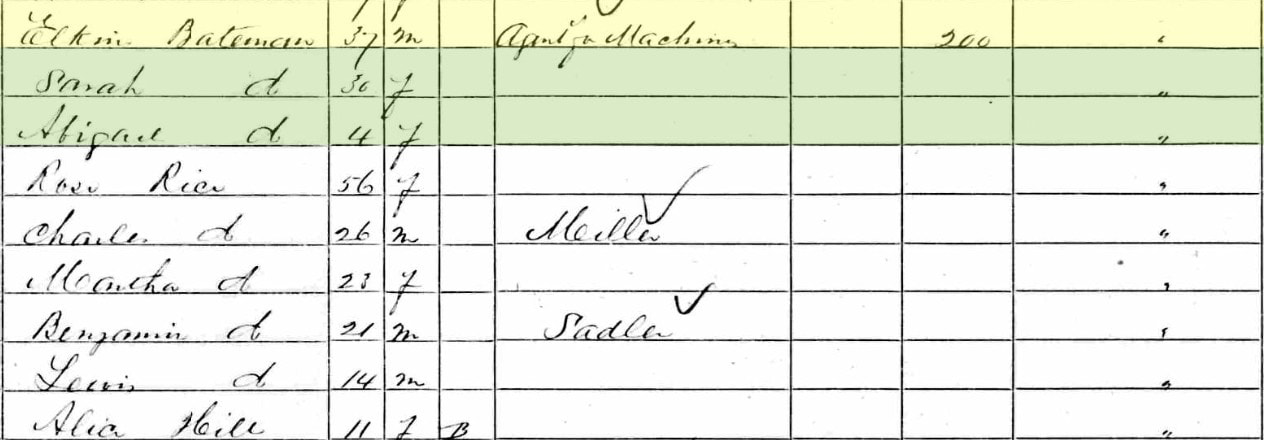

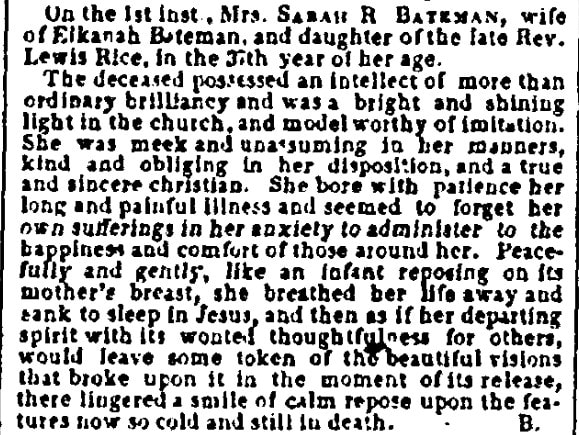

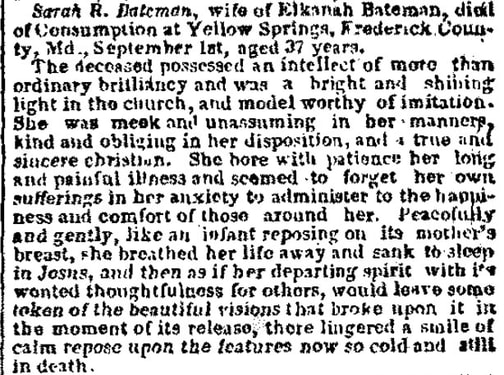

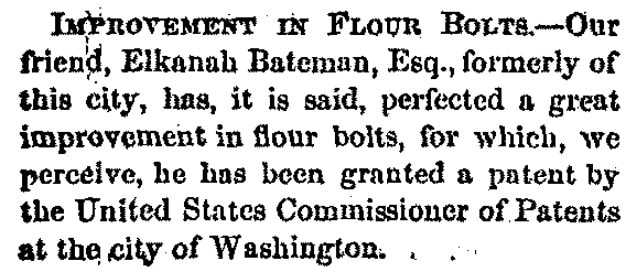

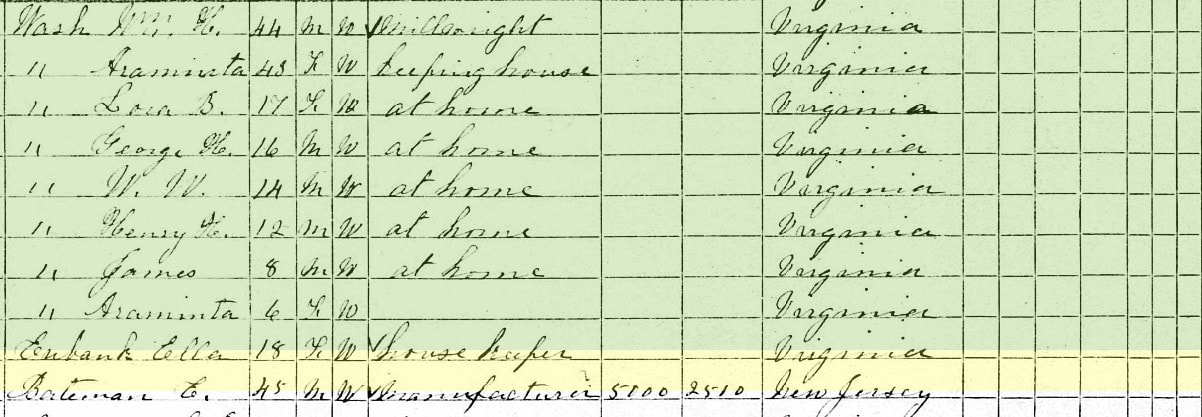

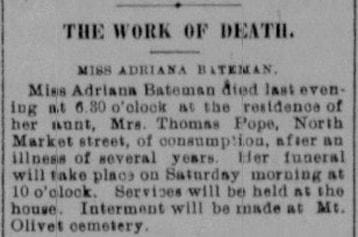

New Year’s Day and I’m actually working at the cemetery. It is a Monday and all, but our Mount Olivet staff is fortunate to have this as an official day off. Hey, I’m not complaining at all, as I truly love my job, and my co-workers to boot. While the workplace setting is open 365 days/year for family visitation and tourist exploration, today is one of a handful of weekdays in which the administrative office is quiet—or dare I say the four-letter word you think I may utter sarcastically? I won’t but it both starts and ends with a “d.” Speaking of which, I became engrossed in thinking of the cemetery’s early history on holidays such as this. This led me to search to see if anyone was ever buried here on New Year’s Day. Knowing that it had to have happened many times over, I reduced my quest to see if the happenstance occurred on Mount Olivet’s first New Year’s Day in 1855, having been officially opened seven months earlier in late May, 1854. Our aged, and very first, cemetery interment book contains a few entries pertaining to two young females buried on January 1st, 1855. These included two daughters of Frederick residents Elkanah Bateman and wife Sarah (Rice) Bateman. The children in question were named Mary Emma ("Mollie") and Alberta. I soon discovered that both sisters are buried beneath a very unique, grave monument called a “cradle grave.” This is not the only design of its kind here in Mount Olivet as we possess several “cradle graves.” These were also known as bedsteads because they mimicked the design of grand beds of the day—complete with marble pieces crafted to resemble a headboard, footboard and side rails. (NOTE: Please read our earlier “Story in Stone” on “cradle graves,” originally published in October of 2020.) The girls’ gravesites are found within Sarah Bateman’s Rice family plot located in Area B/Lot 112. Other members of Sarah’s greater Rice family are buried here beside the two girls mentioned above, and a third sister, Ada Bateman, who lived to be 46 years of age. Elkanah and Sarah, along with Ada, each have their names etched upon a large monument representing the various other nuclear families in the plot. These three family members also have individual footstones simply marked with the decedent's initials: “E.B.,” “S.B.,” and “A.B.” Now with my initial query of a burial on New Years’ answered, my curiosity was piqued as to the question of cemetery business being conducted on a holiday, or so I presumed. Further inspection in the newspapers of the time period showed that “New Year’s Day” was not officially treated as a special work-related holiday per se, like it is today with many bank, business, school and government closures. Time for a bit of history of the day, courtesy of our friends at Wikipedia, which states: “In the Gregorian calendar, New Year's Day is the first day of the calendar year occurring on first day of January. Most solar calendars (like the Gregorian and Julian) begin the year regularly at or near the northern winter solstice, while other cultures and religions that observe a lunisolar or lunar calendar celebrate their Lunar New Year at less fixed points relative to the solar year. In pre-Christian Rome under the Julian calendar, the day was dedicated to Janus, god of gateways and beginnings, for whom January is also named. From Roman times until the middle of the 18th century, the new year was celebrated at various stages and in various parts of Christian Europe on December 25th, March 1st, March 25th and on the movable feast of Easter. In the present day, with most countries now using the Gregorian calendar as their civil calendar, January 1st (according to Gregorian calendar) is among the most celebrated public holidays in the world, often observed with fireworks at the stroke of midnight following New Year's Eve as the new year starts in each time zone. Other global New Year's Day traditions include making New Year's resolutions and calling one's friends and family.[1]The first of January represents the fresh start of a new year after a period of remembrance of the passing year, including on radio, television, and in newspapers, which starts in early December in countries around the world. Publications have year-end articles that review the changes during the previous year. In some cases, publications may set their entire year's work alight in the hope that the smoke emitted from the flame brings new life to the company. There are also articles on planned or expected changes in the coming year.” Many readers are aware that this day is traditionally a religious feast, but since the 1900s it has also become an occasion to celebrate the night of December 31st as New Year's Eve. As a matter of fact, New Year’s Eve, with its parties, public celebrations (often involving fireworks shows) and other traditions focused on the impending arrival of midnight and the new year, has somewhat eclipsed New Year’s Day in attention, if not, popularity in many cultures like ours in the western world. Watchnight services are observed by many, at least those that can stay up until midnight, but to those living in the days when candles and gaslights provided the primary illumination for residents, staying up for hours “after dark” was difficult to do. What was the purpose, other than reading by the fireplace or bed stand candle? Without electricity and all the innovative devices for information and entertainment that would come into existence over the next century, sitting in a chair staring at a grandfather clock or pocket watch was a pretty dull way to spend a night—especially if you had to work in the morning. One early New Year's event that was going on during this period was a grand ball held by the local Chippewa Tribe of the United Order of Red Men. Going back to our story of the Bateman family, I searched the newspapers of the 1850s in Frederick. I saw some interesting happenings on New Year’s Eve and Day, however it generally seemed that January 1st was “business as usual” kind of day. I did see some townspeople that wanted to stray from this notion, and it would all come in good time as they say. Now, let me get you in the mindset of New Year’s Eve (December 31/1854) and New Year’s Day (January 1st) 1855. As a matter of fact, it was a two-day period devoid of “polar bear plunges” and college football “bowl” parades and games. There was no ornate “ball dropping” at midnight in New York City’s Times Square, as that event was first organized by Adolph Ochs, owner of The New York Times newspaper. The legendary “ball drop” was first held on December 31st, 1904 to welcome 1905 as a successor to a series of New Year's Eve fireworks displays held at the New York Times building (hence the name Times Square) to promote its status as the new headquarters of the newspaper. The drop at Times Square has been a center of attention ever since, as it has been held annually except in 1942 and 1943 in observance of wartime blackouts. So by now you certainly have figured out that there was no Dick Clark’s Rockin’ New Year’s Eve in the 19th century either. This latter audio/video extravaganza could not happen way back then because the music aficionado (Dick Clark) would not be born until 1929, and “rock ‘n’ roll” is considered to have had its inception with Elvis Presley recording his first single (“That’s All Right”) in 1954. So if anything else, dazzle your friends and family with the trivia fact that Mount Olivet was a century old when rock music came onto the scene. When you really think about it, the cemetery has served as an open-air “rock amphitheater,” since its opening. No music, just polished forms of marble and granite. As usual, I digress. Mary Emma Bateman was affectionately given the name "Mollie." She was born the day after another holiday we have been proudly celebrating since 1776. The Batemans welcomed their first daughter on July 5th, 1849. She would sadly die at the tender age of two and an half on January 22nd, 1852. Nothing is really known about her, as our cemetery records cite an obituary for this child appearing in the January 28th edition of the Frederick Examiner. No cause of death was given, as it just listed the child’s parent’s names and age of 2 years, 6 months and 19 days. Now this was a time that predated the official opening of Mount Olivet, so Mary Emma Bateman was originally laid to rest elsewhere. I don’t know what burying ground in town that would have been, but my initial thought was based on past experience with the name "Rice" being Germanic, thus pointing perhaps to the Lutheran burying ground at East Church and East streets, or the German Reformed graveyard at the corner of West 2nd and North Bentz streets. I was actually pulling for the German Reformed graveyard (today's Memorial Park) because of an interesting event that occurred in 1852 that I discovered while trying to find the original cemetery young "Mollie" Bateman was originally buried in. When perusing Jacob Engelbrecht’s diary for any info on the Batemans, I learned of an event involving this ancient, former burial ground which still contains about 300 bodies buried beneath the impressive military monuments that adorn the space today. In July (1852), a robbery was committed on the City Hotel and its manager, Mr. Norman B. Harding. Apparently a hand valise/carpetbag containing clothing and $150 worth of bank notes was also gotten, the property of a Mr. Martin of Baltimore. Two days after the theft, the hand carpetbag of Martin was found in the German Reformed graveyard. It had been cut open and was hid under some gravestones. Captain Ezra Doub, an early constable working the case, found that the robber had overlooked all the money which was found “all snug wrapped up in one of the vests” the victim had in his bag. Engelbrecht went on to say that the the robber was later apprehended in Waynesboro, Pennsylvania and committed to jail as he was in possession of several items of Mr. Harding and Mr. Martin. It's a great story, but as for the German Reformed graveyard being the first resting place for Mollie, I would find later that I was wrong. She was most likely buried elsewhere, but more on that in a minute. When perusing Jacob Engelbrecht’s diary for any info on the Batemans, I learned of an event involving this ancient, former burial ground which still contains about 300 bodies buried beneath the impressive military monuments that adorn the space today. In July (1852), a robbery was committed on the City Hotel and its manager, Mr. Norman B. Harding. Apparently a hand valise/carpetbag containing clothing and $150 worth of bank notes was also gotten, the property of a Mr. Martin of Baltimore. Two days after the theft, the hand carpetbag of Martin was found in the German Reformed graveyard. It had been cut open and was hid under some gravestones. Captain Ezra Doub, an early constable working the case, found that the robber had overlooked all the money which was found “all snug wrapped up in one of the vests” the victim had in his bag. Engelbrecht went on to say that the the robber was later apprehended in Waynesboro, Pennsylvania and committed to jail as he was in possession of several items of Mr. Harding and Mr. Martin. It's a great story, but as for the German Reformed graveyard being the first resting place for Mollie, I would find later that I was wrong. She was most likely buried elsewhere, but more on that in a minute. "Mollie's" sister, Alberta Bateman, lived a far shorter life of just four days. She was born on December 27th, 1854, a belated Christmas gift to her family. Just as the holiday flies by for so many of us, the infant would be gone by week’s end, dying on New Year’s Eve. Our records show that she was buried here in Mount Olivet on New Year’s Day, proving that staff members were on hand to perform the task. Alberta’s death gave cause for the Batemans to reconsider Mollie’s grave location. The decision was promptly made that the sisters be buried together in Mount Olivet. They were placed side by side, and the cradle grave shown earlier would soon be crafted for use over "Mollie" and Alberta Bateman's final resting places. I would learn that the girls’ maternal grandfather, Rev. Lewis Rice, would be re-interred to this same burial plot in Mount Olivet’s Area B/Lot 112 on January 2nd, 1855. His obituary, which I found in the Baltimore Sun, gave me a better clue of where "Mollie" (Mary Emma Bateman) had been originally buried. This was the Methodist Episcopal Church’s graveyard that once existed east of Maxwell Alley (formerly known as Middle Alley) on the south side of East 4th Street. It was now time to wrap things up by seeking information on the Bateman parents, Elkanah and Sarah. Starting with Mrs. Bateman, I located an obituary that perfectly described her life and character. Her death occurred a decade after she had her father and daughters buried in Mount Olivet. Sarah's actual death date was September 1st, 1866. However, I had to smile when I saw her birth date in our cemetery records. It was January 1st, 1828. I suddenly saddened realizing that she had buried her baby daughter Alberta on her 27th birthday. This woman’s lengthy obituary appeared in both the Frederick Examiner and Maryland Union newspapers. This was generally an uncommon thing for women of the period. Elkanah was now left to raise daughter Adrianna “Ada” into adulthood. She was born in Frederick in 1856, and was around 10 at the time of her mother’s death. The head of the family was also the bearer of a very interesting name. I soon found its meaning defined as follows: “In the Book of Samuel in the Torah and Old Testament, Elkanah was the husband of Hannah and the father of her first son, Samuel. This Hebrew boy's name is an alternative way of spelling Elqānāh. It means "god has purchased," and comes from the words el, meaning "god," and qaneh, which means "to acquire." Our subject was born in Fairfield, Cumberland County, New Jersey on December 19th, 1823. Unlike his wife, he had been baptized in the Presbyterian Church. He was raised in New Jersey by parents Elkanah Bateman (1788-1833) and wife Sobrinah Elmer (1788-1855). Our subject, Elkanah, Jr., married Sarah Rice in 1842 in Cumberland, NJ. Rev. Rice appears to have been a minister here before relocating to Frederick. This likely explains not only where Elkanah met his wife, but also why the Bateman family came to Frederick, Maryland, with Sarah following her parents to town. Elkanah was a laborer early in life and worked within the realm of milling and was dedicated to the making, packing and the delivering of flour. He and his father-in-law (Lewis Rice) were partners in a milling business, trading as Rice & Bateman, until the death of Lewis Rice. The location of this operation was known as "Keefer's Prospect" and contained 21 acres with a mill, buildings and water rights obtained from Michael Keefer in 1850. It was known as Keefer’s Mill and was situated on Ballenger Creek, just east of where Ballenger Creek Pike crosses over the tributary. It was sold in 1853, a year after Rev. Rice’s death. In the 1859/60 Williams' Frederick Directory City Guide and Business Mirror, Elkanah is said to have been either living or working on the east side of Love Lane (East Street) between Patrick and Church streets. This is the site of today's Everedy Square, and I'm assuming that Bateman was located closer to Patrick Street because of the former site of a Lutheran cemetery on the southeast corner of Love Lane and East Church Street. The family lived in Yellow Springs, north of Frederick City in the 1860 census, taking up residence with Sarah's mother and other siblings. Since I grew up out that way, I venture a guess in wonderment regarding any connection Elkanah ever had with an old mill that was located at the intersection of Walter Martz Road and Yellow Springs Road. This no longer exists in a new landscape of traffic circles, and was in a state of decay when my elementary school bus passed it in the mid-late 1970s. A year after Sarah’s death, I found an article in the Maryland Union newspaper praising Elkanah for an important advancement made in “bolting” flour. His invention led to having a US patent registered under his name. Here’s a description from a website for the Old Stone Mill national historic site in Delta, Ontario, Canada which helps differentiate bolted flour from traditional milled flour. “The flour from the grindstones is a mix of the entire wheat kernel which consists of bran (the outer layer), endosperm (food for the seed) and germ (the root). This is our Whole Grain flour - it contains every part of the kernel. However, it is a very heavy flour and cannot be used in all baking applications. To be able to have a finer flour (one rises more to make a lighter bread and can be used for things like cakes), the flour needs to be separated to extract the finer portion. This is done using a machine called a bolter. The bolter contains spinning screens with various hole sizes. The flour enters one end of the bolter, the end with the finest screen. The lightest part of the flour, the fines and superfines come out from this screen. Gravity carries the remaining flour, separating out the "middlings," the "shorts," and finally, the bran."  Footstone of Elkanah Bateman Footstone of Elkanah Bateman Elkanah moved to Virginia sometime after this as I next found him living in St. Annes Parish in Albemarle. He was living with millright William H. Wash and continuing his “rising” career in the flour business. He made a career change in the late 1890s though. On February 21st, 1897, Elkanah Bateman was appointed postmaster for Cabell-Floyd, Virginia. I last found him within the 1900 census. He was living in Madison, Virginia (also within Cumberland County). It’s interesting to note that he started and ended life in Cumberland County, just two different states (New Jersey and Virginia). Elkanah Bateman would breathe his last breath in early July, 1901 in Virginia. His body would be brought to Frederick and laid beside the other members of his immediate and extended family in Area B. I looked in vain for his obituary, but couldn't find it anywhere. Perhaps a deeper dive is needed in Virginia newspaper archives. Our cemetery records state that he was placed in the grave on July 4th, 1901. Damn, somebody was working here at Mount Olivet on that holiday as well! Just over a year later, the last member of the Bateman family died, leaving no surviving heirs for this family that came by way of New Jersey. Adriana Bateman would never marry. She died on July 23rd, 1902 and was buried next to the two sisters she never had the chance of knowing, and the same that were buried on New Year's Day, 47 years earlier. Happy New Year, and thanks for your support of us at Mount Olivet and these “Stories in Stone” articles throughout 2023.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed