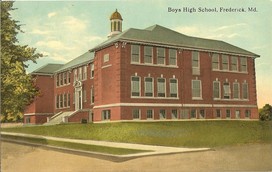

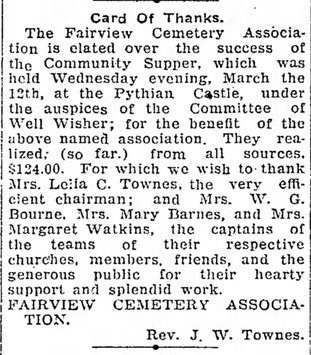

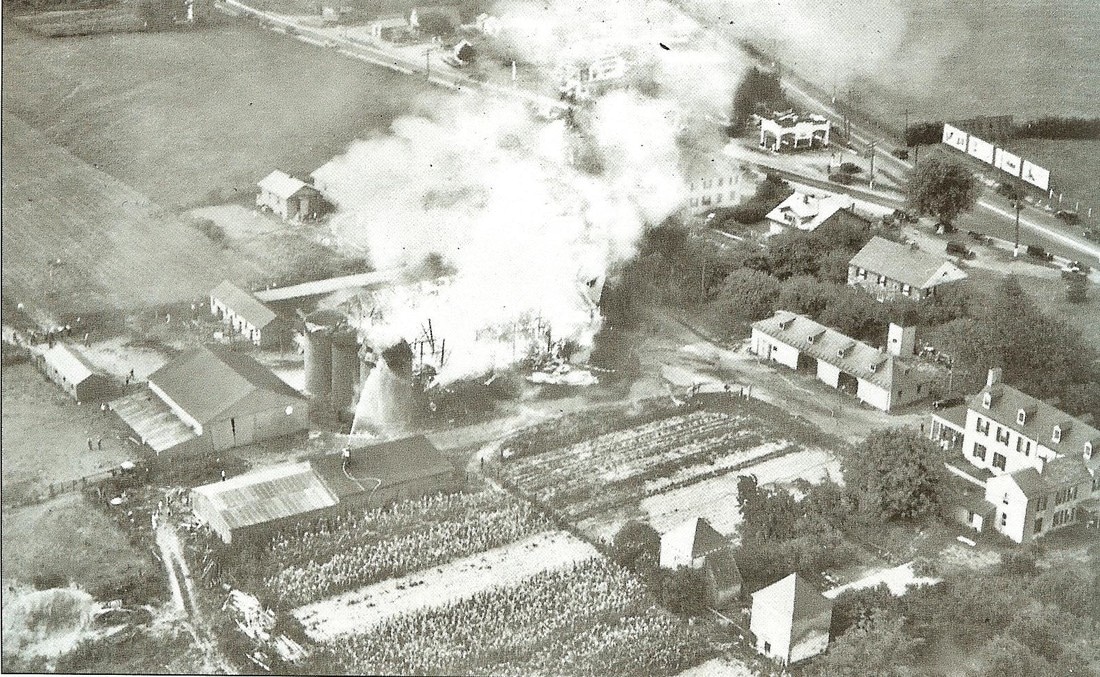

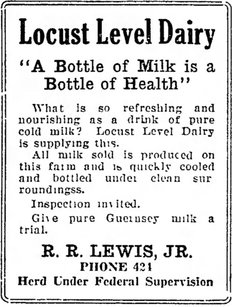

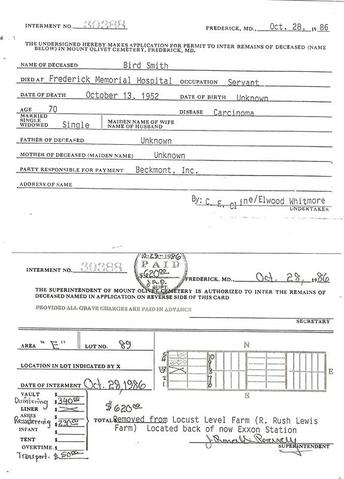

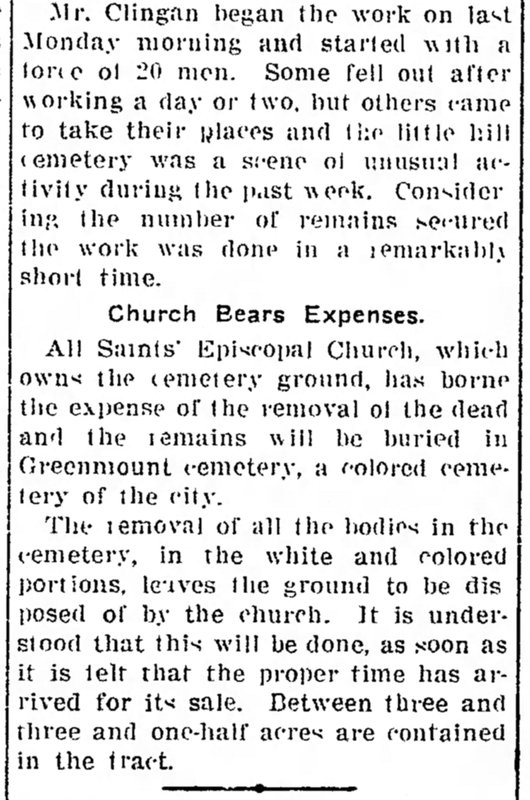

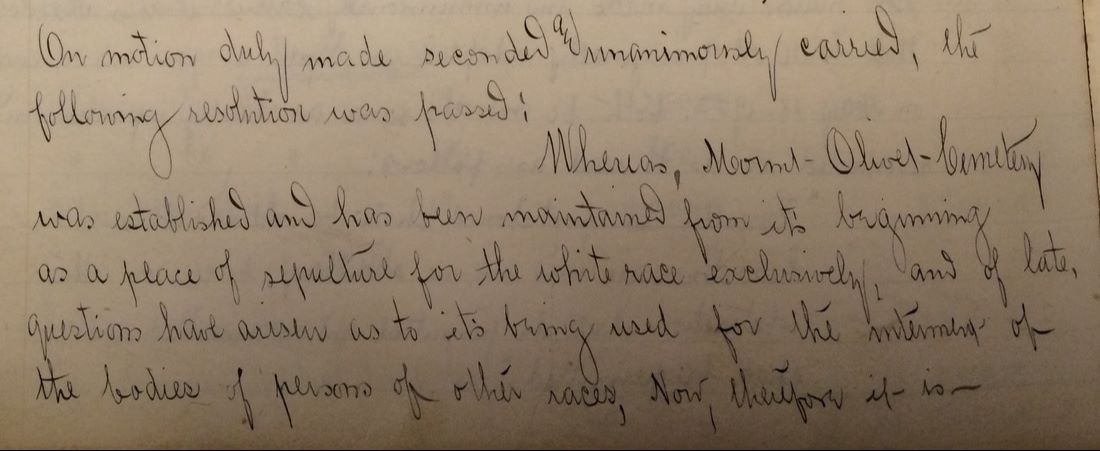

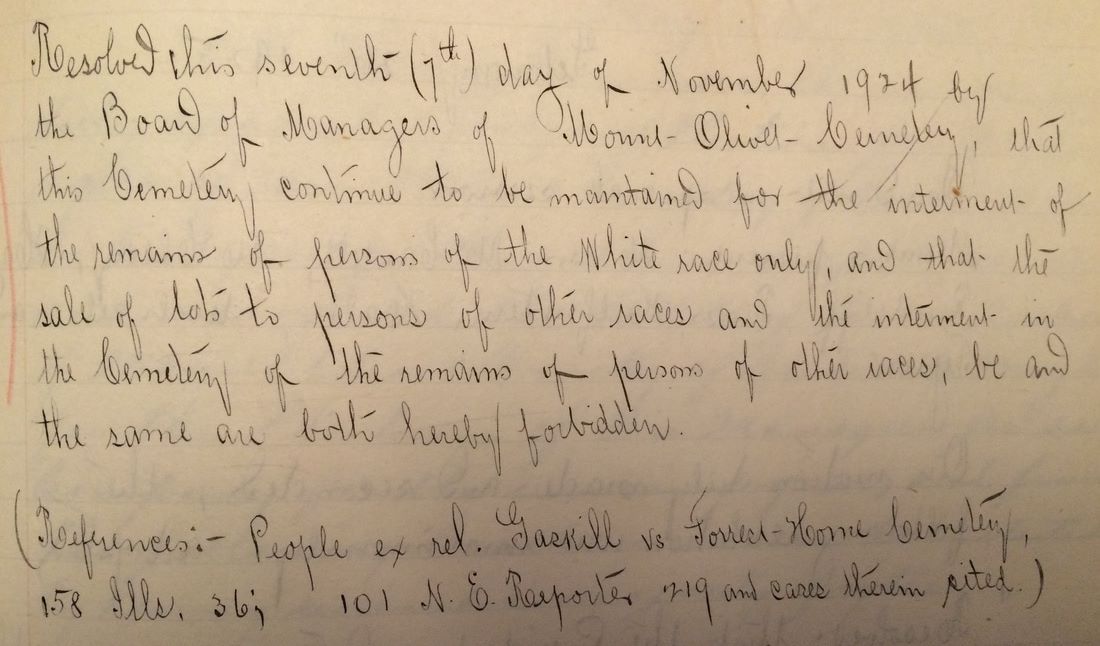

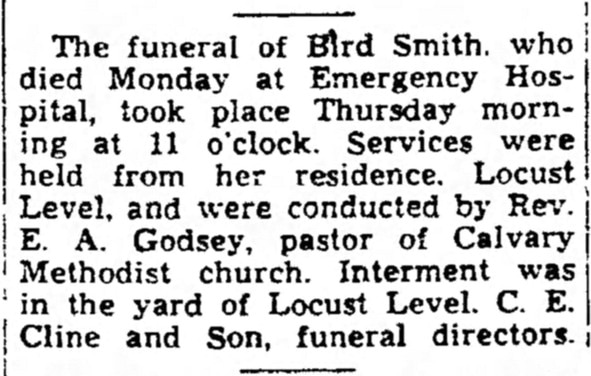

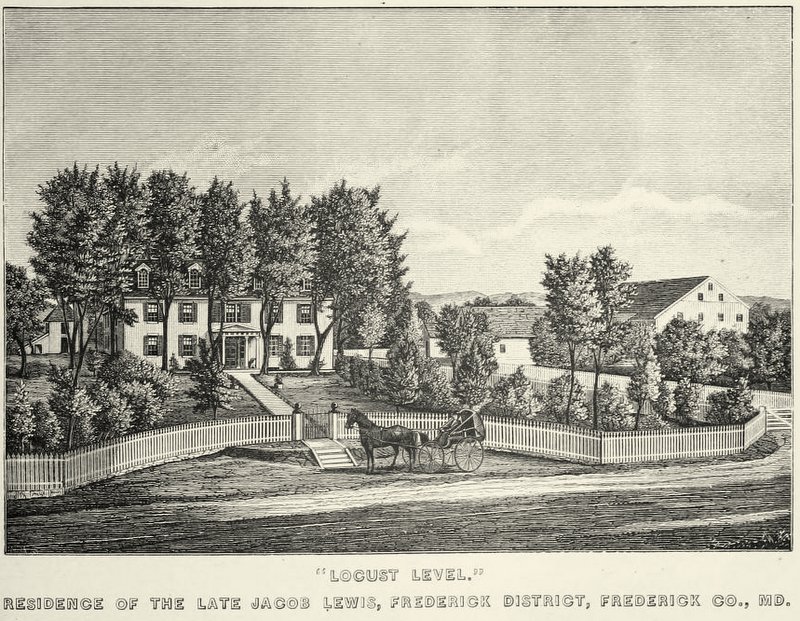

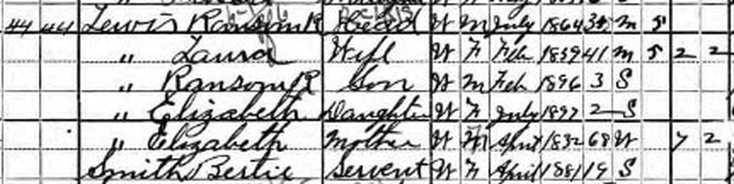

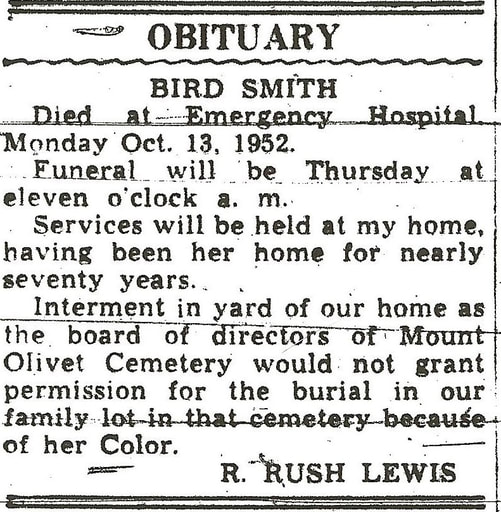

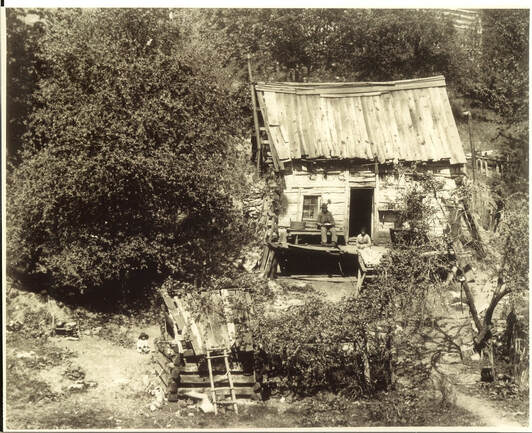

(Part III) Sidestepping a Color Barrier: The first Black Residents buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery3/11/2017  Frederick City Hospital (ca. 1906) Frederick City Hospital (ca. 1906) The year was 1913. As the defunct All Saints’ Cemetery of Frederick was being eyed as an eminent site for business and industry along Carroll Creek, the Greenmount Cemetery property on the northwest side of town was becoming increasingly more important and attractive—especially to people not looking to purchase a burial plot. Although major real estate development was being planned for this suburb of downtown, Greenmount also represented a strategic opportunity for a burgeoning young medical facility. The Frederick City Hospital organization had been formed in 1897 with the aim of establishing, and maintaining, a central place of care for the surrounding community. This became a reality on May 1st, 1902, when a 16-room structure opened on Park Place, a long-gone, house-lined street that once paralleled Trail Avenue. Miss Emma J. Smith, first president of the Frederick City Hospital, graciously gave seven acres of land—land that bordered Greenmount Cemetery. The hospital grew rapidly over its first decade of existence. Wings were added, boasting the name of Hood, a tribute to James Mifflin Hood and wife Margaret Scholl Hood, Frederick’s “benefactress extraordinaire.” A nurses’ school and home would be built in 1911-1912 on a neighboring site in close proximity to both the hospital and cemetery. The Frederick Boy’s School would simultaneously be constructed as a public secondary school for boys. This structure served as such until 1938 when it would be converted into a junior high school which would carry the moniker as the Elm Street School. The Building backed up to the south edge of Greenmount.  Greenmount Cemetery (center of picture) located on the south side of W. 7th St. ca. 1899 Greenmount Cemetery (center of picture) located on the south side of W. 7th St. ca. 1899 Unfortunately, or fortunately, Greenmount had much more land than possibly needed. Developers knew this, and so did the hospital. This could also be the reason to explain why the Working Men’s group changed from a beneficial order to a stock company. Whether an offensive maneuver, or a defensive stand to stave off other uses, the Frederick City Hospital made the Greenmount trustees a purchase offer for their unused parcel—roughly half of their property. This happened in 1913, for $3,000. The Greenmount land sale did nothing to deter plans for the willing acceptance of bodies from the “Old Hill” colored burying ground in early 1914. I’m assuming the Vestry of All Saints’ Church was required to purchase re-interment lots, as they had done the year before with Mount Olivet. All in all, 380 bodies were moved to Greenmount in April, 1914. Seven years after the Working Men’s Stock Company sold half of Greenmount’s Cemetery land to the Frederick City Hospital, an offer was made by the hospital to purchase the entirety of the largest black cemetery in Frederick’s history. Expansion was of key importance, but there was also a psychological component—most of the hospital's patients were happy to look out their window and see a beautiful green mountain, but not a cemetery. Forty years in business had netted nearly 1,000 burials, not to mention the bodies re-interred from the All Saint’s colored burying ground in 1913. Many of the families related to burials at Greenmount are said to have moved away from Frederick in order to find to work in metropolitan areas such as Washington, DC, Baltimore, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. Other families, pardon the pun, simply “died out.”  Boys High School of Frederick Boys High School of Frederick The talk by many in both the black and white communities back in 1913 forecasted the future of both Greenmount and Laboring Sons as one day becoming abandoned cemeteries. Articles in the local newspapers shared the demoralizing view. But Frederick had seen earlier white cemeteries fade in time, their land used for other purposes like that of the All Saints’ Cemetery. In 1920, the Working Men’s group sold their burial ground to the hospital, described as 146' and 6" along the south side of W. Seventh St. and 689' back, adjoining the Boys High School lot (later Elm Street School). I strongly believe that the subject of openly allowing blacks the opportunity to be buried in Mount Olivet had to be broached in 1922-23. Although I have yet to see a published account, it’s hard to imagine the question not being asked in light of the climate of growth taking place. The City of Frederick, Frederick City Hospital and real estate developers likely thought about the potential need to relocate the deceased residents of Greenmount, not to mention the urgent need of finding a new burial ground. Laboring Sons Cemetery was not an option. It had been in freefall for years. Articles of Laboring Sons unkempt and deteriorating condition, peppered with occasional brush fires and trash dumpings did not make this “burial ground” an ideal choice at this time. It would languish for another 25 years until something was done with/to it. Couple the need of a suitable new location for blacks to be buried with William Jarboe Grove’s folksy local history book (The History of Carrollton Manor) which must have been read by many in town upon its release in 1923. The importance here was that Mr. Grove had let the proverbial “cat out of the bag” so to speak, by publishing the fact that Mount Olivet allowed a black person in Hester Houston, be buried within the cemetery’s gates in 1896. This wasn’t a reburial or charity case, but a one-time slave/domestic with an at-need burial. Whatever the case, something prompted the Mount Olivet Board of Managers to issue the following resolution during one of their quarterly meetings, held November 7th, 1924:  The resolution plainly stated that Mount Olivet was a place for white burials only. As I said earlier in Part One of this article, the original bylaws of the cemetery did not contain any written restrictions based on the race of the deceased. I also could not find anything in the cemetery’s Board meeting minutes book as well—these dating back to 1852. The cemetery was simply set up as a non-denominational, community (of shareholders) owned cemetery. I believe there was a silent push to allow blacks, or possibly reinter blacks (from Greenmount) at hand. The resolution of November 7th firmly set out to put that talk to rest—or better yet, “bury it.” At the same time, perhaps this language was designed to send a firm message to the cemetery’s superintendent and lot-holders thinking they could freely dictate what could be done with funerary property. Keep in mind that the time period between 1915 and 1925 was especially turbulent for black-white relations. The D.W. Griffith film “Birth of a Nation” came out in 1915 and played to sold-out crowds across the country, including a multi-night engagement at Frederick’s City Opera House. Local theaters were segregated, having separated entrances and seating areas for black patrons, if indeed, they were allowed entry at all. “Colored” soldiers returning from Europe and military duty after World War I found newfound hostilities back home, as many whites refused to acknowledge their equivalent role in protecting the country. This began with the “red summer” of 1919, in which racism and brutality against blacks soared all over the country, both north and south. Incredible riots broke out in Washington DC during the summer of that same year. Frederick had not been immune to lynchings and Klan activity, it happened here, and not just rural settings out in the county. Jim Crow was real, and the climate of Frederick was not ready to abolish the “separate but equal” policies that were a way of life. Schools, hospitals, stores, restaurants, and municipal parks were all segregated here in Frederick—even places like the YMCA. This was only 50-60 years removed from the mixed emotions and sympathies portrayed here through the white citizenry during the American Civil War.  Fundraiser activity for Fairview Cemetery (Frederick News, March 15, 1924) Fundraiser activity for Fairview Cemetery (Frederick News, March 15, 1924) Back to the Frederick burying ground dilemma, a formidable solution was gained by a group of active and progressive religious, business and social leaders of town. A new cemetery association was formed, and its name borrowed from a nearby thoroughfare within a stone’s throw of Greenmount Cemetery was utilized. This was Fairview Cemetery. The Fairview Cemetery Association of Frederick County, Inc. was established in 1923. A committee of Rev. John W. Townes, M. E. Jenkins, and Dr. Charles E. Brooks was assembled to find and purchase an appropriate lot of ground. Another committee, comprised of William R. Diggs, Dr. U. G. Bourne, Dr. Charles Brooks, Thomas Clark, Albert Dixon, George Norris, M. E. Jenkins and Rev. Townes, was tasked with raising the funds to purchase the lot. On October 12th, 1923 the Association paid $500 as down payment on their $5,500 purchase from L. Edgar Betson and his wife Dora. The 6-acre property was located on the eastern approach to town on E. Church Street extended, better known as Gas House Pike.  Present day site of Greenmount Cemetery (1880-1926). This is a parking lot for Frederick Memorial Hospital, located directly south of intersection of W. 7th Street and Toll House Avenue. (photo taken from atop the hospital's parking deck facility) Present day site of Greenmount Cemetery (1880-1926). This is a parking lot for Frederick Memorial Hospital, located directly south of intersection of W. 7th Street and Toll House Avenue. (photo taken from atop the hospital's parking deck facility) The land deal would be completed in 1924, interments began in late 1924. Burials in Greenmount would continue through 1926, however the hospital had decided the previous year that no more burials would be allowed here. With Greenmount’s closing, people of color looked at their new cemetery with hope and adoration— filling rapidly in those infant years thanks to as many as 284 Greenmount burials moved to the Fairview Cemetery in 1927. One of which was Greenmount cemetery founder Richard Jackson (died 1910) and his wife Emily (died 1899). Interestingly, twenty years later (1945), the family of the last official president of the Laboring Sons Cemetery Association, John Makel, would choose Fairview over his own cemetery to serve as his final resting place. Through all of this, the trustees of Laboring Sons would fail to move any of their cemetery inhabitants to Fairview. As Mount Olivet represents the sum of the city’s earliest burying grounds, Fairview has carried the “tongue in cheek” moniker of being "the Mount Olivet of the black community. " Historic monuments, pleasant looking grounds and “a who’s who of Frederick” go far to prove that point, while black residents of Frederick have continued to make Fairview the largest and leading black burial ground for 90+ years. “A Bird in Hand” In 1952, a 70-year-old black woman named Bird Smith breathed her last. Uterine cancer would take her life, one that had mostly been spent working as a life-long domestic/maid for a local farm family living just south of town near the local landmark of Evergreen Point.  Today's view of the once-glorious "Locust Level" estate and manor house. (looking south across US I-70 from the Costco parking lot) Today's view of the once-glorious "Locust Level" estate and manor house. (looking south across US I-70 from the Costco parking lot) Ms. Smith actually served multiple generations of the Ransom Rush Lewis family on their 200-acre farm, named Locust Level. This property is only a short distance south of Mount Olivet. In fact Mr. Lewis, Sr. delighted in purchasing lots for his family that were in clear view of his farm. We know this location today by commercial landmarks replacing the former manor farm first established in the 1700’s. Here one can find Costco, Interstate 70, plus properties located off Francis Scott Key Drive: the Econo Lodge, Enterprise Rent-a-Car and Sheetz.  Aerial view of the Lewis family's Locust Level manor estate from August, 1934. A fire had engulfed the main barn on the property. Note the location of Evergreen Point in the upper right of the photo. This is the intersection of MD355 and MD85, today a major interchange located roughly a quarter mile south of Mount Olivet on S. Market Street.  Advertisement in the Frederick News (June 30th, 1923) Advertisement in the Frederick News (June 30th, 1923) Before we get to the few details known about this woman of color boasting an interesting name, let’s talk about her employer. Mr. R. Rush Lewis had a successful career as a leading farmer and prominent businessman. His father, Jacob Lewis had originally moved to Frederick from Chester County, Pennsylvania and purchased Locust Level in 1854. Born in 1864, R. Rush Lewis spent his youth on the family farm and stayed active in agricultural pursuits, particularly dairy farming. In addition, he was chosen president of the First National Bank of Frederick in 1909, and served as president of the G. & L. (Garber & Lewis) Baking Company, vice president of the Borough Peoples Fire Insurance Company, and a director in the Central National Bank. I haven’t found anything substantial on Ms. Smith other than the fact that she was a Maryland native, born in April 1881, and never married. Her unusual name was written as Bertie in an early census, perhaps giving a hint that her real name was possibly Bertha or Roberta. Bird Smith faithfully served three generations of the Lewis family. She was a true part of the family, playing a “nannie” type role to Rush and Laura Lewis’ two children—Ransom Rush, Jr. (b. 1896) and Elizabeth (b.1897). Unfortunately, Bird Smith would not leave the nest of Locust Level farm site after her passing. Ransom Rush Lewis had gone to Mount Olivet, in order to make burial arrangements for Bird within his pre-purchased family plot (Area E Lot 89). His request would be rejected by the cemetery’s Board of Managers. They referenced the minutes of the November 7th, 1924 resolution upholding “white only” burials. The policy was again written, verbatim, within the Mount Olivet minutes book in early November, 1952, nearly 30 years after it s first writing. The Lewis family was deeply upset in seeing their lifelong friend and family member denied access for burial. The cemetery was literally a next door neighbor to the Lewis farm. R. Rush Lewis had already buried two wives here, first wife Laura Yerkes Lewis in 1924, and Margaret Duvall Lewis (second wife) in 1947. Lots had been purchased for R. Rush’s children and faithful Bird.  R. Rush Lewis R. Rush Lewis R. Rush Lewis didn’t settle for help and memorialization in Fairview Cemetery, as you would expect. Instead, he had Bird Smith buried in the yard of Locust Level Farm. It must have been extremely frustrating for Mr. Lewis, a man of considerable wealth and influence in Frederick, but powerless in this particular situation involving race discrimination. All the while, Mr. Lewis took out a scathing classified ad in the Frederick News, made to look like an obituary. In doing this, he directly called out Mount Olivet’s Board of Managers, chastising them for not allowing the burial of Bird Smith based solely on the color of her skin. It was a bold and historic move. I’ve heard that he started a litigation process against the cemetery, but did not follow through because the cemetery had the right to enforce its own rules because it was a private cemetery.  Lewis family plot in Mount Olivet Lewis family plot in Mount Olivet R. Rush Lewis died in 1958. Years passed as Bird Smith would eventually be the last reminder of the Lewis family on the property. The farm had been deeded to the Frederick Home for the Aged and City of Frederick in 1858 before Mr. Lewis’ death. However, it was subsequently sold by the Home for the Aged to developers in 1964. The property became bisected by a superhighway (US70) in the late 1950’s. The proud Locust Level Farm had traded in its dairy parlors for gas pumps— the Pure Oil Truck Stop was opened on the north side of the former Lewis property in December, 1965. The grand manor house of the 1700’s was demolished, to make room for an Exxon gas station. Evergreen Point and MD routes 355 and 85 sprouted into a major commercial cluster of car dealerships, fast food restaurants shopping venues anchored by the Francis Scott Key Mall, opened in the late 1970’s. Bird Smith’s “cemetery of one” remained, about 30 yards from the highway to the rear of the gas station, next to an asphalt parking lot. Her gravesite, outlined with bricks, was buttressed by stanchions to safeguard it from being hit by lawnmowers. A small 2’x1’ granite monument stood at the head of the grave and boasted a Bible passage from Revelations 2:10. It read: “In loving memory of Bird Smith who has served on this farm for seventy years. Be thou faithful unto death and I will give thee a crown of life.” In 1986, a representative for a company called Beckmont, Inc. out of California visited cemetery superintendent J. Ronald Pearcey at his office. Beckmont was the development company that owned the present property that once belonged to the Lewis family. The representative explained to superintendent a quandary he had on his hands. There was an opportunity to build a motel on the former farm site on the parcel immediately behind the gas station, and along the highway. However, there was one small problem, Bird’s gravesite. It had to go. Superintendent Pearcey was in his fourth year at the helm of Mount Olivet, but had originally started back in 1966. He immediately recalled hearing the story of Bird Smith from his predecessor Robert Kline. Mr. Kline was not the superintendent in 1952, but was on the cemetery staff. He explained to Pearcey that he felt very guilty with the stand made by the cemetery’s board against the Lewis family’s wish to bury Bird Smith in the family lot. Mr. Kline reiterated that there were sympathetic members on the board, as well as staff members like himself. However, there were also strong lot holders who helped in pressuring the board to hold firm to a “white only” policy. On a personal level, Mr. Kline grew up in an environment in which he had many black friends and a cerebral approach to "separate but equal." Kline’s father once ran a canning factory in town, boasting many black employees, many of which became close friends and confidantes of the Kline family. There were now no obstacles in place as there had been three decades earlier. Pearcey shared Bird’s story with the Beckmont representative, and suggested that he would attempt to make contact with Elizabeth Lewis Peters, daughter of R. Rush Lewis. Pearcey thought to himself that this could be an opportunity to make things right after all these years. He subsequently met with Mrs. Peters, who lived on the corner of Record and W. Church streets in downtown Frederick. The 88-year-old woman immediately supported the idea with Pearcey’s assurance that the job could be handled correctly and with dignity. Tuesday, October 28th, 1986 began as a somewhat pleasant day with showers forecasted for the afternoon. The gravesite in Mount Olivet had been opened and sat ready to receive its long overdue decedent. The special day was October 28th, 1986. Superintendent Pearcey, current-day foreman Tyrone Hurley and other staff members journeyed the quarter-mile to the Locust-level site and Bird Smith’s grave with necessary tools needed for rare occasion of grave removal, not placement. The team carefully exhumed the burial vault that had been placed within the ground of the old Lewis home place. They placed this within a van for transfer up the Georgetown Pike to the cemetery.  Bird Smith's interment card at Mount Olivet (dated October 28, 1986) Bird Smith's interment card at Mount Olivet (dated October 28, 1986) Thirty-four years, and fifteen days after her death at Frederick Memorial Hospital, site of the former Greenmount Cemetery, Bird Smith’s body made its way through the large iron-gated entry of Mount Olivet Cemetery. The lifelong black servant was finally placed where she was supposed to be, amidst her extended Lewis family, in plain view of her former home of Locust Level. Over this duration, the Civil Rights movement had conquered “separate but equal,” opening the gates for equality. The staff placed Bird Smith in her new resting place and it came time to close the grave. The gravestone from Locust Level was brought as well and awaited its final placement atop the head of the grave. There was just one final step left, which involved a promise made by Superintendent Pearcey to Mrs. Peters. She wanted to inspect the grave before. It was afternoon, and the skies had opened-up, drenching the area with steady rain. Pearcey ventured downtown to the Court Square area of Frederick to pick up the widowed octogenarian. He recalls she was particularly quiet and somewhat pensive. The superintendent drove her to the nearest spot that the grave could be seen from a cemetery lane. The rain continued to fall, and Mrs. Lewis was familiar with the location as she had been attendance for other funerals here including her parents and brother who had died in 1972. Pearcey was taken aback when Mrs. Peters asked if she could inspect the grave from up-close. He gladly obliged, grabbing an umbrella from under the seat then rushed around to open Mrs. Peters door. Holding the umbrella over the diminutive woman, Superintendent Pearcey escorted Mrs. Peters to Bird’s open gravesite. Once there, Mrs. Peters stared intently down the hole, saying nothing. Ron says that a sense of great relief seemed to be-fell the senior, perhaps releasing the weight and emotional pain associated with the initial burial rejection, her family’s disappointment/anger and a 34-year time passage before Bird’s mortal remains could reunite with the rest of her former family members here at Mount Olivet. After about a minute, Ms. Peters told Pearcey that she was satisfied and it was time to head back home. Less than three years later, Elizabeth Peters would take her place beside Bird and the others. She had witnessed the “righting of a wrong” in today’s context. Segregation was a practice that was a known part of life, and in this story’s case—death, in earlier times. The story of Bird Smith is a fascinating one. It is also a painful and embarrassing moment in the cemetery’s rich story. But such is the history of any person, place or thing—a collection of trials and tribulations, successes and failures. The cemetery is richer to have Bird Smith, Hester Houston, Maria Harper, Martha Snowden, Abe Brighton and Julia Hill among its interred population. These individuals somehow triumphed the institution of “separate but equal,” to be laid to rest in Mount Olivet, either by accident or design. This is especially important when viewed in context to cemeteries and burial places—distinct places where the journey of life is complete, and our God judges us not by the color of our skin, but simply by our earthly good deeds and charity toward others. We gladly invite any further information and, or, photographs pertaining to Bird Smith.  History Shark Productions Presents: "UP FROM THE MEADOWS: The Class" Are you interested in learning more about the incredible African-American heritage story of Frederick City and Frederick County, Maryland? Check out this author's latest, in-person, course offering: Chris Haugh's "Up From the Meadows: The Class" as a 4-part/week course on Tuesday evenings starting March 12th, 2024 (March 12, 19, 26 and April 2). These will take place from 6-8:00pm at Mount Olivet Cemetery's Key Chapel. Cost is $79 (includes all 4 classes). For more info and course registration, click the button below.

7 Comments

3/12/2017 09:19:40 am

Outstanding series....my heart is filled with so much emotion for these blessed souls....thank you for sharing rich history new to me....and the context past and present

Reply

Jocelyn Wetzel

3/12/2017 06:05:45 pm

Wonderful series Chris.

Reply

H. Walker Smith

3/13/2017 11:54:04 am

Interesting reading. I would like to point out a minor error in the account regarding Grove's "History of Carrollton Manor". The publish date is 1928, not 1923 as stated. I have a copy that belonged to my father. Opposite page 141 is a picture of then "Smith's Mill" in Doubs, referred to as "Carroll's Mill" in the book. Taken in 1927, standing on the porch are my father, Walker R. Smith, and grandfather H. Ray Smith, the mill's owner.

Reply

3/13/2017 01:02:45 pm

Hi Mr. Smith,thanks so much for taking the time to comment and share info regarding "Smith's Mill." As for the the publishing of the book, I think you have a later edition than the original that is in my collection. Upon closer inspection you are correct in correcting me as the work was made available two months earlier than I had read with an old press release in early 1923. Mr. Grove dates his preface (within the book) March 29th, 1921. The cover of my original copy boldly says 1922 on the cover.

Reply

H. Walker Smith

3/13/2017 01:45:29 pm

I take it that the reply I received via email doesn't allow a return email so I'll comment here.

Reply

3/13/2017 02:42:34 pm

Hi Mr. Smith, thanks again for the info on your incredible collection! Superintendent Pearcey knew your dad. Please stop over and see us someday, we would very much like to talk history with you and hear more about the collection. In the meantime, feel free to contact me anytime at my work email: [email protected] or phone (301)662-1164.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed