|

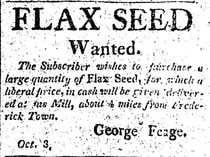

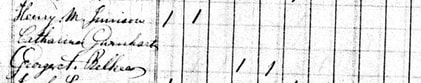

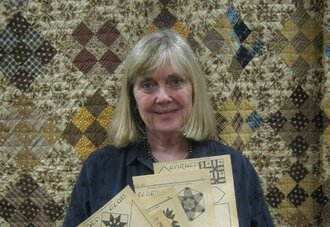

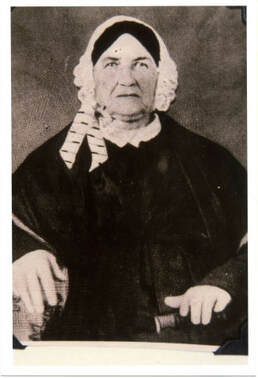

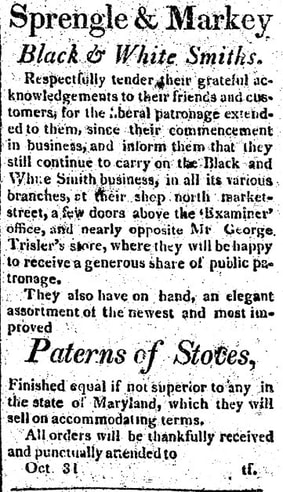

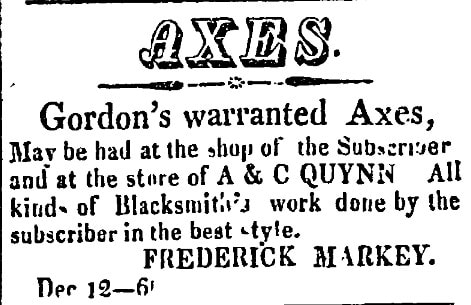

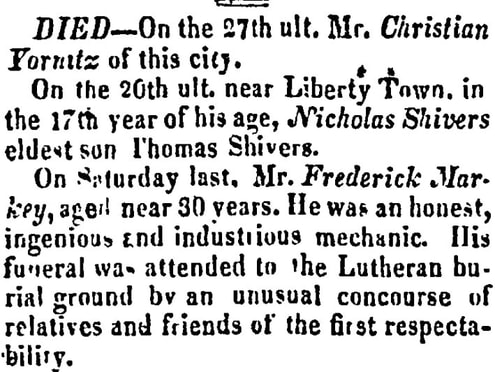

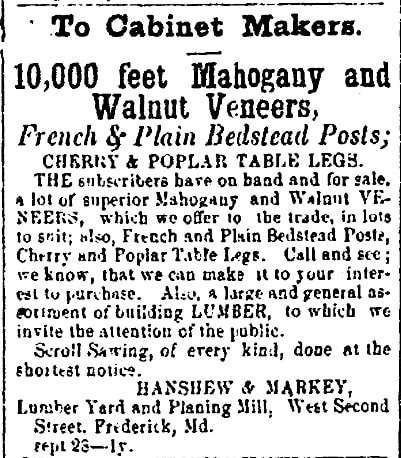

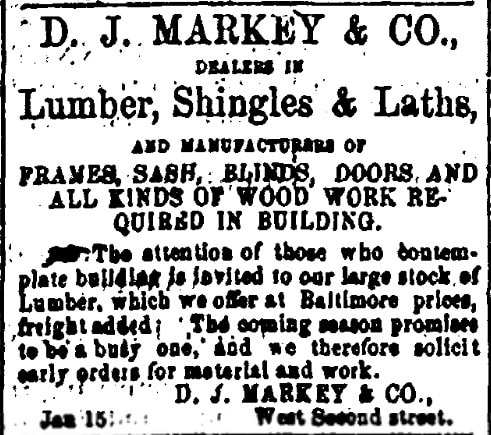

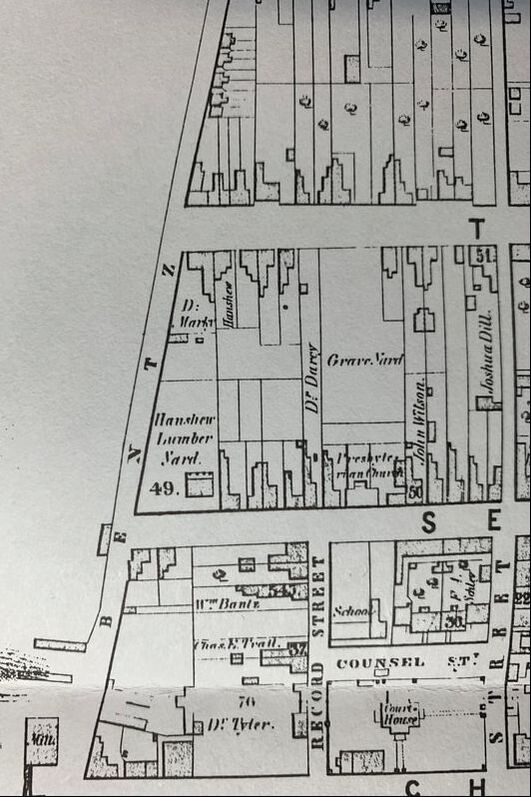

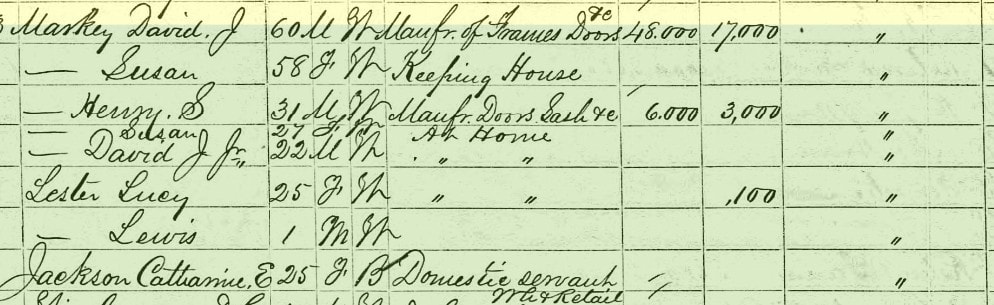

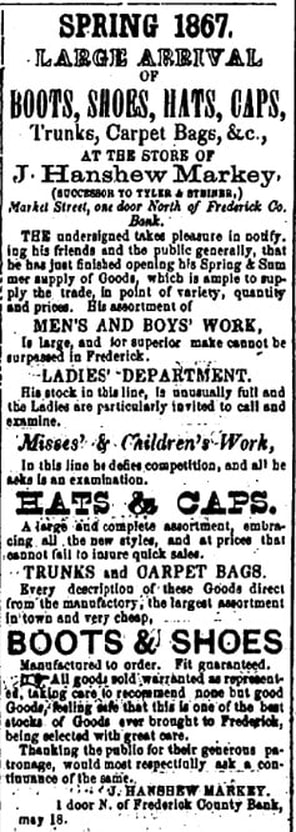

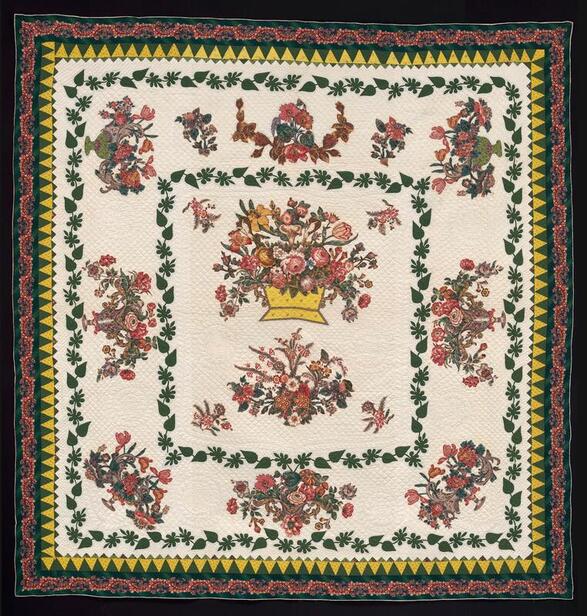

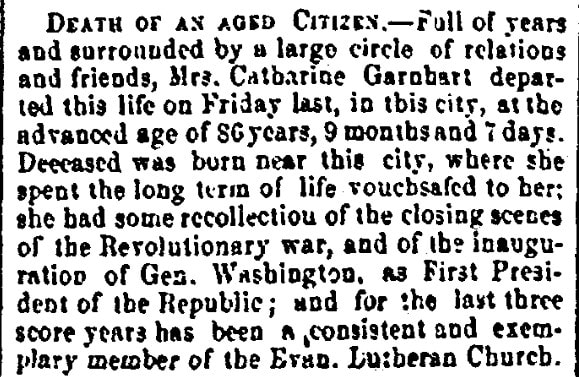

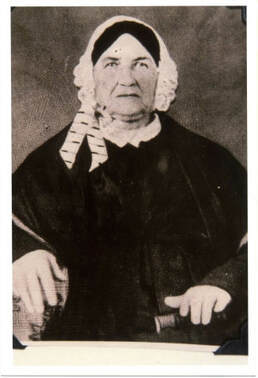

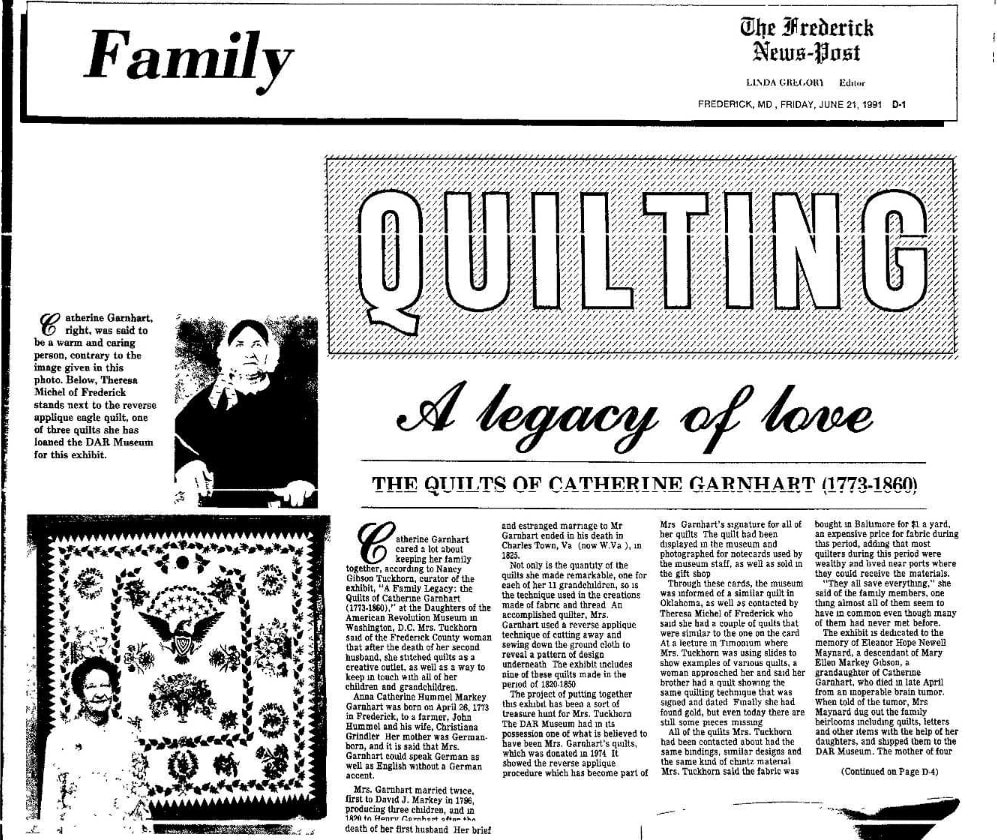

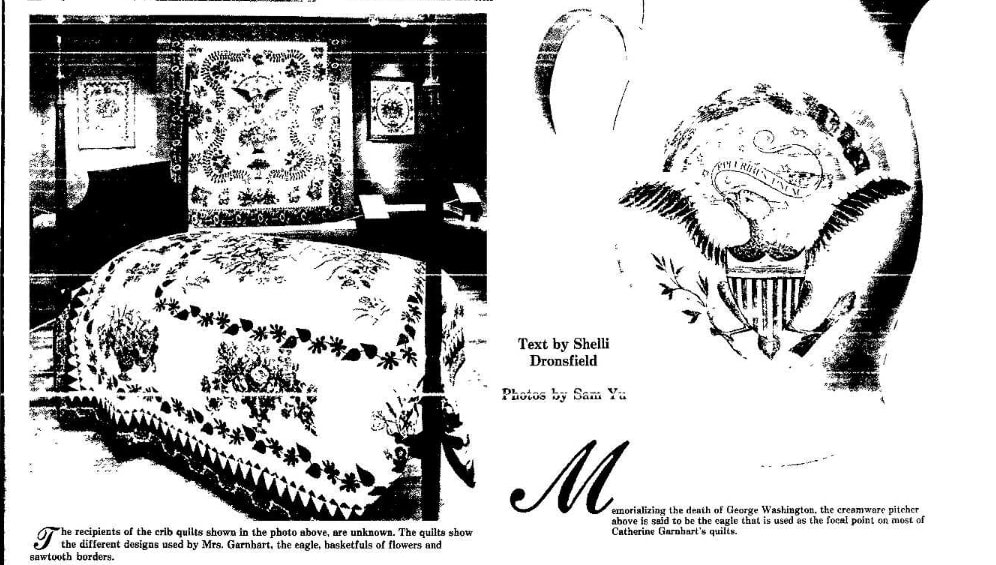

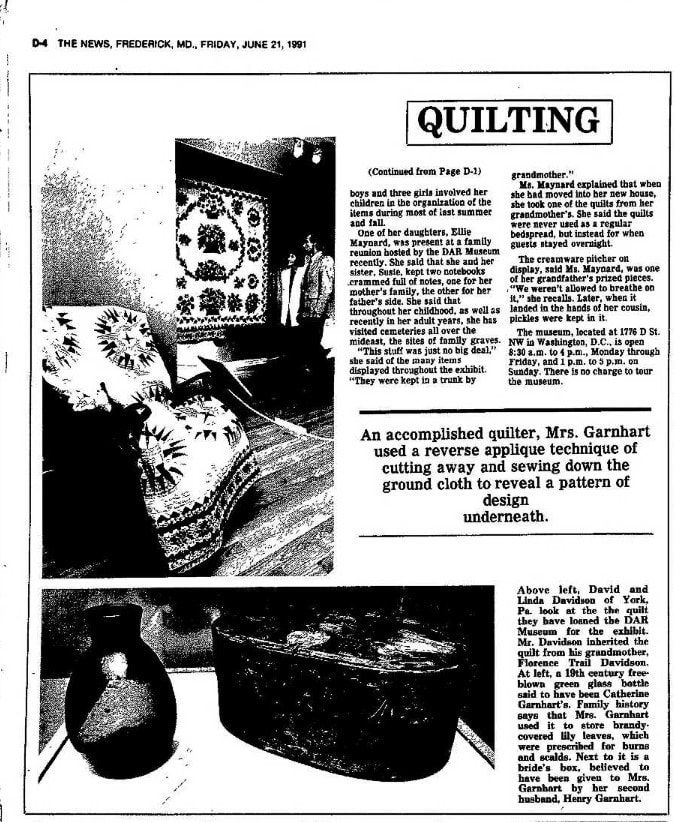

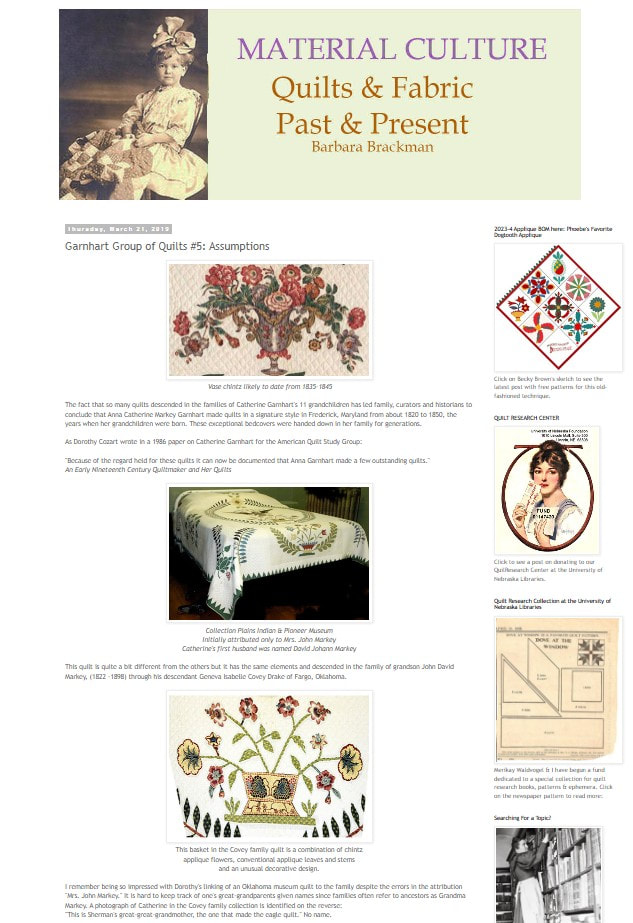

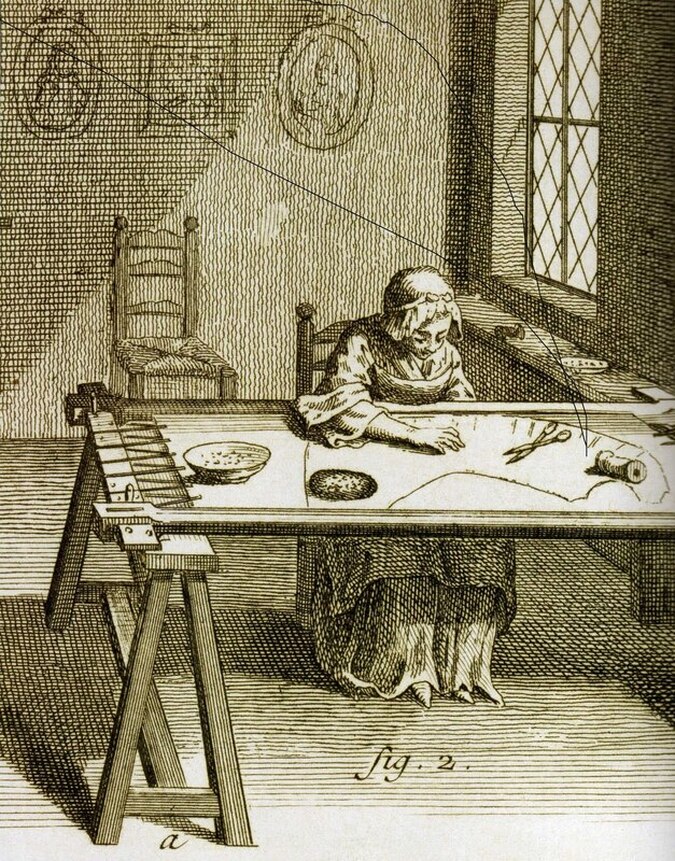

“In your life, the people become like a patchwork quilt. Some leave with you a piece that is bigger than you wanted and others smaller than you thought you needed. Some are that annoying itchy square in the corner, and others that piece of worn flannel. You leave pieces with some and they leave their pieces with you. All the while each and every square makes up a part of what is you. Be okay with the squares people leave you. For life is too short to expect from people what they do not have to give, or were not called to give you.” -Anna M. Aquino Nobody knew this concept better than Anna Catherine (Hummel) Markey Garnhart. Not only is her name a “stitched-together masterpiece” unto itself, but her life and family relationships seem to have been so as well. Add to this the fact that her chief hobby in life appears to have centered on the craft of quilting. Works of hers are well-known by applique quilt and coverlet experts as well as collectors around the country. Examples of her craftsmanship can be found in both private and museum collections. One such repository includes the DAR (Daughters of the American Revolution) Museum in Washington, DC, where one of Garnhart's signature quilts, "the Eagle Quilt," is displayed and bears as its central object an eagle. A corresponding label states that: "Eagles were a hot design trend in the decorative arts, throughout the United States and not only in quilts, from the early years of the republic through our semicentennial in 1826. Garnhart made four eagle quilts, probably all before about 1830, and all with her extensive use of reverse appliqué. The sawtooth borders are typical of this region." Catharine Garnhart's prime contribution to the trade comes in the form of applique quilting. Applique is a needlework technique in which one or more pieces of fabric are attached to a larger background fabric to create pictures or patterns. The fabric can be attached by hand, machine or fused. The word comes from the French meaning "applied or laid on another material." Catharine is said to have shopped in Baltimore, paying up to a dollar per yard for her chintzes - a lot of money back then. Over fifty small prints appear throughout Garnhart’s quilts, and over twenty large-scale chintzes. Many prints appear in several quilts. Many of this Catharine's quilts can be seen online including a site called the Quilt Index (www.quiltindex.org) and various other websites.  Evangelical Lutheran Church and Graveyard (c. 1854) Evangelical Lutheran Church and Graveyard (c. 1854) Catharine Garnhart Anna Catharine (Hummel) Markey Garnhart was born on April 16th, 1773 on the eve of the American Revolution. Her parents were immigrants including father John Hummel (1743-1781), whose mother brought him to America in 1749 from Wurttemberg, Germany, and twice-married Christiana Catharine (Grundler) Hummel Feaga (1747-1849), who emigrated to the New World (from Germany) in 1754. John Hummel would take part in the American Revolution and died in battle as a result. He served as a corporal in Capt. Jacob Baldy’s company of the 6th Battalion of Berks County (PA) militia commanded by Col. Joseph Hiester (this stated by Sons of the American Revolution records). Corp. Hummel’s grave is said to be located beneath the Frederick Evangelical Lutheran Church and cannot be seen or photographed. Anna, better known as “Catharine,” was a life-long resident of Frederick. Her mother, the fore-mentioned Christiana Grundler, immigrated to America as a young girl with her mother, father and four older sisters. During the passage, Christiana’s mother died and was buried at sea. After arriving in America, Christiana's father placed her with "adoptive" parents Friedrich and Catharina Wittmann, who needed the help of another child, and raised her in Frederick. These were (her future husband) Johann Hummel’s mother and step-father. Christiana was married for the first time in 1771 to husband Johann Hummel, a farmer, mill owner, and land investor. She gave birth to five Hummel children (including our subject “Catharine”) before losing her husband, Johann Hummel, in 1781. He was only 38 at the time. I couldn’t find the final resting place of this gentleman, but his namesake son, John Hummel (1777-1826) is buried in Mount Olivet’s Area NN. After struggling with Mr. Hummel's estate, Catharine’s mother married again in 1782. Her new spouse was a Hessian soldier and prisoner of war named Johann Philip Fiege (1750-1829). This former mercenary soldier came to America to fight under the British flag. He would be captured at the Battle of Yorktown and would be imprisoned in Frederick. Like many Hessian soldiers kept here in Frederick, they were loosely guarded at the aptly named barracks located a block from our cemetery’s front gate.  Political Intelligencer (Feb 6, 1819) Political Intelligencer (Feb 6, 1819) Upon war’s end, Philip Fiege and his comrades were welcomed wholeheartedly by Frederick’s German community, and decided to stay in this new country instead of going back to Germany where their leaders sold them out to Great Britain in most cases. Mr. Fiege had experience with mills in Germany, and soon made a successful business from the mill on Johann Hummel's property. He would eventually change the spelling of his name to Feaga and his sons would continue to prosper with the milling operation. In time, the hamlet where the family lived and work would take the family name of the former prisoner of war and principal landowner—Feagaville. This is located about four miles southwest of Frederick City on MD route 180. In this marriage, Christiana Feaga would have four more children. Philip Feaga died in 1829 and was originally buried in the Evangelical Lutheran Churchyard. He would be re-interred in Mount Olivet’s Area F/Lot 78 in 1860. Christiana died in January of 1849, and was moved here to Mount Olivet from Evangelical Lutheran as well. According to a great, great-grandson's family history, Christiana was a devout member of the Evangelical Lutheran Church and a financial supporter. She enjoyed good health and spoke English with a German accent while living to be over 101 years of age. Christiana outlived all but four of her nine children and remained financially independent throughout her 22 years as a widow. The young Catharine (Hummel) experienced the loss of her father at age eight, and the trials and tribulations of her mother’s life, but with the accompaniment of many siblings it appears. For a girl of her times, she would have been well-versed in cooking and home-keeping tasks, but it’s likely that her well-rounded mother taught her things such as writing, music and needlework. The latter being a given! Catharine married David Johann Markey (1771-1820) in 1796. They had three known children: Frederick Markey (1796-1827), David John Philip Markey (1809-1885) and Christina Catharine Markey, b. 1812 , about whom nothing is known as she likely died in infancy. David Markey worked as a wheelwright and served at least one term as Constable and was later Clerk of the Sheriff's office. Catharine’s husband, like her father, fought for independence against the British but in the second go-round with the War of 1812. Markey was one of the townspeople recruited by Capt. John Brengle and Rev. David Schaeffer on August 25th, 1814. He served in Brengle's company and is believed to have been engaged in the defense of Baltimore which helped win Francis Scott Key immortal fame thanks to a catchy song. David Markey died in 1820 and was originally buried in the All Saints’ Protestant Episcopal burying ground before being re-located to the Markey Family Lot in Area E/Lot 86 in 1868. The Markey family lived in Frederick Town and, in 1818, Catharine Markey is on record having bought what is now 218-220 N. Market Street from Jacob Gonzo. Following David Markey's death, Catharine would remarry. This gentleman was a widower with deep ties to neighboring Jefferson County, Virginia (at the time). His name was Henry Garnhart (b. 1754), and from what I could find was a tavern operator earlier in life before coming to Frederick. Sadly, Catharine would endure the loss of her adult son Frederick in 1827. Frederick Markey was formerly a partner on a blacksmithing/white-smithing business in town. He was married to Elizabeth Dill (1800-1866) and left three children.  Catherine Garnhart as head of household in 1840 US Census Catherine Garnhart as head of household in 1840 US Census Catharine’s second husband, Henry, would die the following year in 1828. He was buried in a small, family cemetery near Hall Town (today's WV), but would later be moved to Edge Hill Cemetery in nearby Charles Town (WV). I’m theorizing that our subject, Catharine, worked out her grief from both of these great losses by keeping busy with making her appliqués, once again defined as "ornamental needlework in which pieces of fabric are sewn onto a large piece of fabric to form pictures or patterns.” Catharine Garnhart still had her son David John Philip Markey at arm's reach, and "Jack" (as he was commonly called) was one to be extremely proud of. While still in his twenties, Catharine’s son perceived the need for a planing mill to produce window sashing, doors and moulding in the city. Trained as a carpenter and familiar with lumber milling thanks to his mother’s family, David John Philip "Jack" Markey partnered with John Hanshew to build and operate a highly successful planing mill at the northeast corner of North Bentz and West Second Street. Today this is the site of Calvary Methodist Church. The firm also acted as a building contractor with projects ranging from housing to the parsonage of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Frederick where Markey also served terms as elder and alderman. He was a prominent citizen of the community, co-founder and board member of the Mutual Insurance Company of Frederick and city councilman, alderman and Tax Commissioner. The home residence of David J. P. Markey and family was built near the mill around 1839 at the southeast corner of North Bentz and West Third Street (134 W Third). His marriage of over 52 years to Susan Bentz produced eight children, including Frederick shoe merchant John Hanshew Markey (1835-1895), father of David John Markey (1882-1963) who would be responsible for forming Company A of the Maryland National Guard, and this unit’s original home, the Frederick Armory, located cata-corner from the site of the family planing mill.  A memorial stone for David John Markey, great-grandson of Catharine Garnhart. This gentleman was quite impressive as he served as a politician, career Army officer, businessman, and college football coach. He served as a Major in the United States Army during the Spanish-American War, World War I and World War II. He was a candidate for United States Senator from Maryland in 1946. Although buried in Arlington National Cemetery, this memorial cenotaph can be found in the Markey family plot in Mount Olivet’s area E Anna Catharine (Hummel) Markey Garnhart was blessed with eleven grandchildren. She would make a quilt for each (including nine large quilts and three crib-size quilts which survive today). In addition to the previously mentioned John Hanshew Markey, most of these grandchildren are buried here in Mount Olivet. Out of David J. P. Markey’s eight children, all but one, Daniel Scholl Markey, are here. (D.S. Markey moved to San Francisco).  Appliquéd Chintzwork Quilt, by Catharine Garnhart. Two grandchildren’s quilts ended up in the same branch of the family, so it’s unclear whether this was made (ca. 1845) for Rebecca Markey or her sister Susan, both children of David Markey. Part of an exhibit in Colonial Williamsburg called "Art of the Quilter" in the Foster and Muriel McCarl Gallery (Gift of David and Linda Davidson)  Barbara Fritchie (1766-1862) Barbara Fritchie (1766-1862) As for Catharine, she had died at the age of 86 on February 3rd, 1860. She would be spared the stress and strain of the American Civil War, having lived herself through the two wars for independence. It's also safe to assume that she knew Barbara Fritchie, ten years her senior, but I'm sure they were both "cut from the same cloth." These ladies have the same bonnet and beautiful smile as evidenced by the fortunate fact that we have surviving photographs of both women. (Note: I'm being very sarcastic about the smiles.) Two days after her death, the body of Anna Catharine (Hummel) Markey Garnhart would be the first to be buried in the Markey family lot in Area E. As already mentioned, first-husband David Markey, and son Frederick, would be removed from Evangelical Lutheran to be buried on each side of her. Decades later, David J. P. "Jack" Markey and wife Susan would be placed here, and their children (Catherine's grandchildren) Lucy Emma Russel Markey and David Jacob Markey. Other family members, and generations, would surely follow to more recent times. Anna Catharine (Hummel) Markey Garnhart was so much more than I could find recorded about her. In writing and researching this story, its not hard to see the similarities between a patchwork quilt, and a family tree. That's something that will stick with me, as will my memories of my own loving grandmothers, and their role in "enveloping" families with love, tradition, support and kindness. When done correctly, it's kind of like that warm and euphoric feeling you experience on a cold winter day or night, when you wrap yourself in the cocoon of a heavy blanket or duvet. All this hits home as my grandmother Haugh even knitted me an Afghan when I was a kid, and it continues to be a prized possession. How many of you have a quilt or homemade textile made by your grandmother or great-grandmother? I originally learned about this woman from my good friend Theresa Mathias Michel of Frederick’s Council Street. She showed me a picture of one of Catherine's quilts that she actually owned, and had told me of Mrs. Garnhart’s fame in quilting circles. I soon learned that a collection of her quilts is being displayed at the DAR headquarters in Washington as I relayed at the start of this "Story in Stone." While digging through online newspaper archives, I was pleased to discover an article showcasing Mrs. Garnhart’s quilting work in the Frederick News-Post in 1991. Mrs. Michel and her quilt were featured as the article promoted the fact that a special exhibit of Garnhart's quilts was occurring that summer at the DAR Museum in Washington, DC. I soon learned a bit more about Catharine's handiwork by consulting the internet, specifically the website and blog of Barbara Brackman, a quilter, quilt historian and author. I would soon learn that Ms. Brackman was not just an enthusiast, but one of the country’s leading authorities on the subject, not to mention being a “Hall of Famer.” She was inducted into the Quilters Hall of Fame of Marion, Indiana in 2001.  Barbara Brackman Barbara Brackman Barbara has written numerous books on quilting during the Civil War including: Facts & Fabrications: Unraveling the History of Quilts and Slavery, Barbara Brackman's Civil War Sampler, Barbara Brackman's Encyclopedia of Appliqué, America's Printed Fabrics 1770-1890, Civil War Women, Clues in the Calico, Emporia Rose Appliqué Quilts, Making History–Quilts & Fabric from 1890-1970, and Quilts from the Civil War, all published by C&T Publishing. Her Encyclopedia of Pieced Quilt Patterns contains more than 4000 pieced quilt patterns, derived from printed sources published between 1830 and 1970. In 2019, Barbara Brackman conducted a deep dive of research on our subject Catharine Garnhart. She wanted to see if the Frederick woman was truly an originator and innovator of designs which would be later copied and found around the country. Ms. Brackman theorized that the Garnhart group of quilts are products of Maryland's commercial quilt-making workshops, seeing these as a parallel style to the more abundant Baltimore album-style quilts. She had her doubts, thinking that Catherine Garnhart was just a customer who purchased similar quilts—a generous grandmother who could afford to buy some fashionable luxury gifts for her family. Brackman carefully studied existing specimens and conducted intensive detective work, publishing her findings in the six posts below: Barbara Brackman concludes: "Catharine Garnhart bought her family quilts, possibly as gifts for grandchildren, probably purchased in the Baltimore vicinity where a group of seamstresses were selling basted and/or finished blocks and quilts in the kind of workshop I was looking for in Frederick. This group of designers and seamstresses making the Garnhart group may predate the high-style Baltimore album group which dates from about 1845 to 1855, but it seems likely that the two types of quilts overlapped in the late 1840s." I can’t say I know much, or, honestly anything substantial, about the textile trade, but Ms. Brackman certainly does. Read the blogs for yourselves, and feel free to post your own theories and conclusions in the comments after the story. Regardless of the authenticity of Catharine Garnhart’s quilts and talents, the greater family of Ms. Garnhart is quite a tapestry itself, one which certainly typifies the quote featured at the outset of this article, especially the following three lines:

“You leave pieces with some and they leave their pieces with you. All the while each and every square makes up a part of what is you. Be okay with the squares people leave you.”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed