|

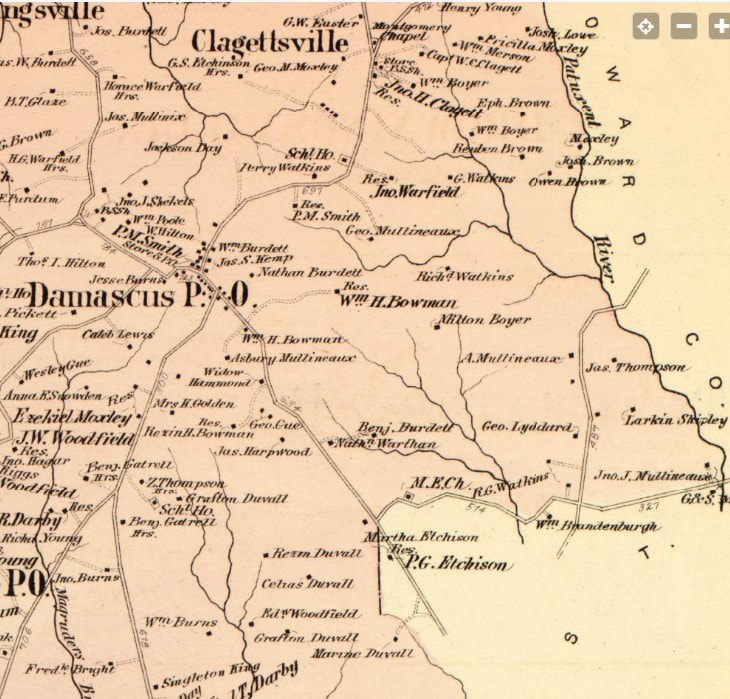

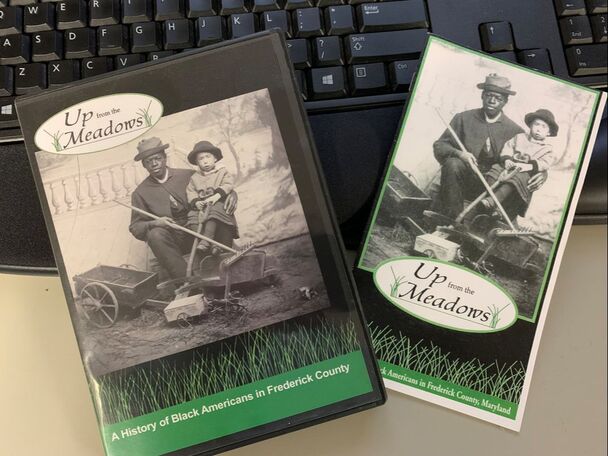

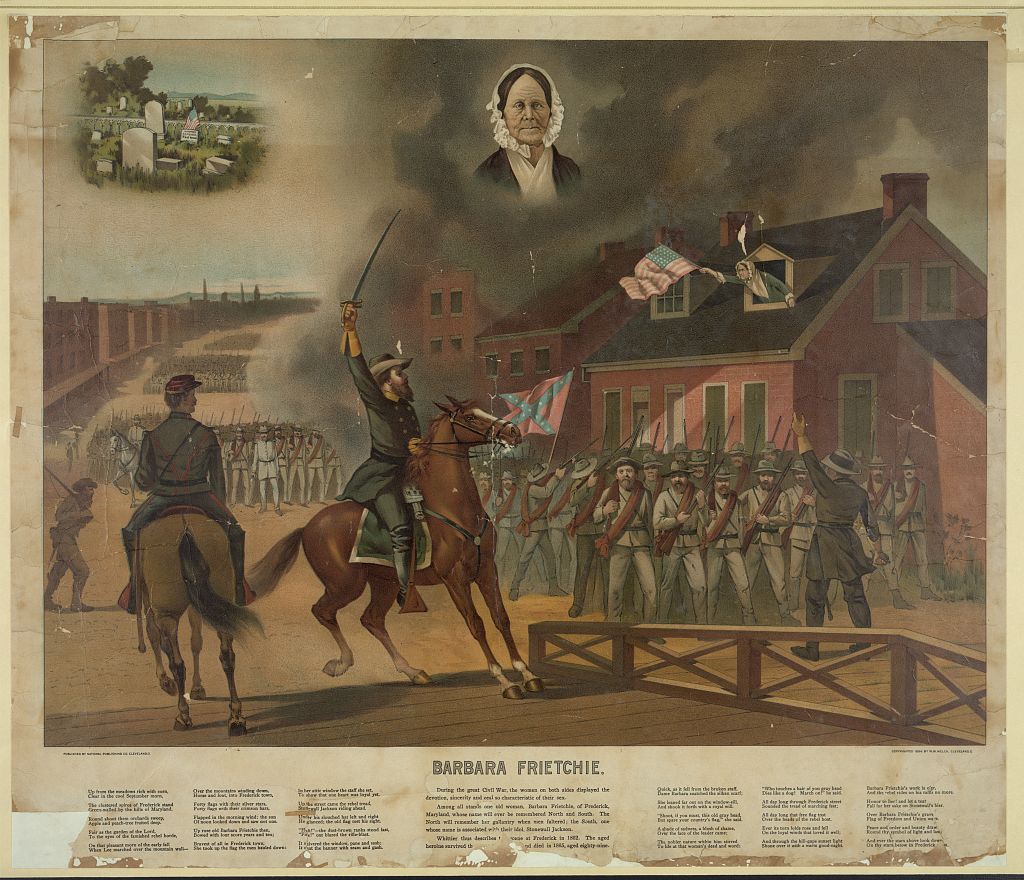

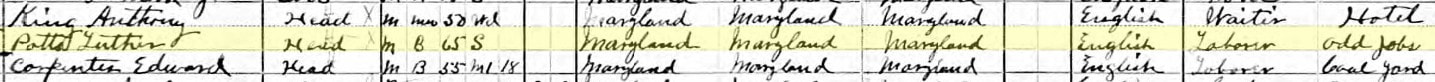

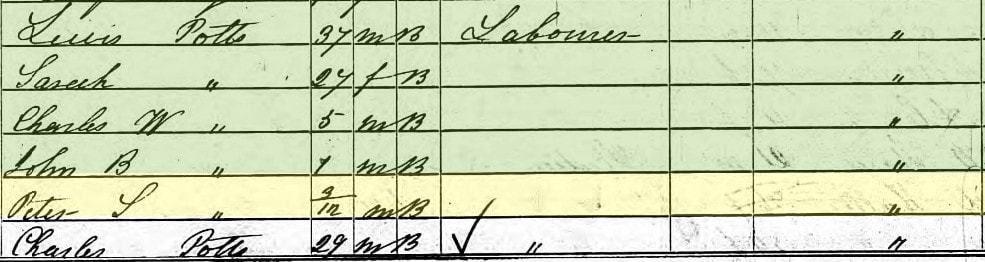

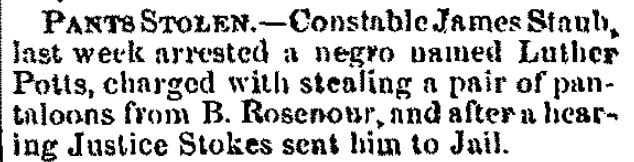

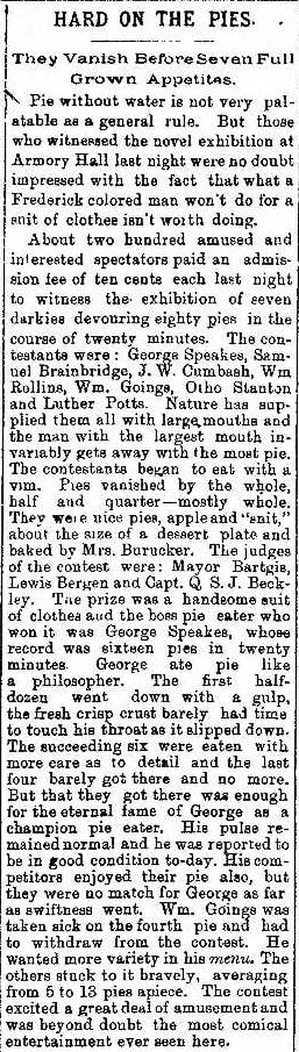

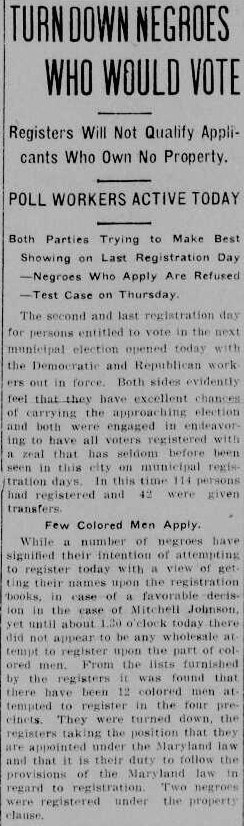

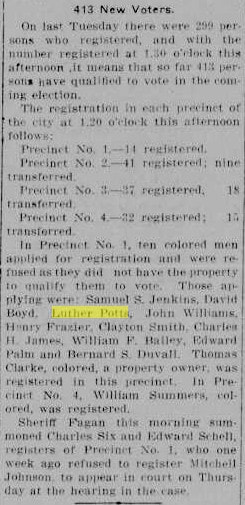

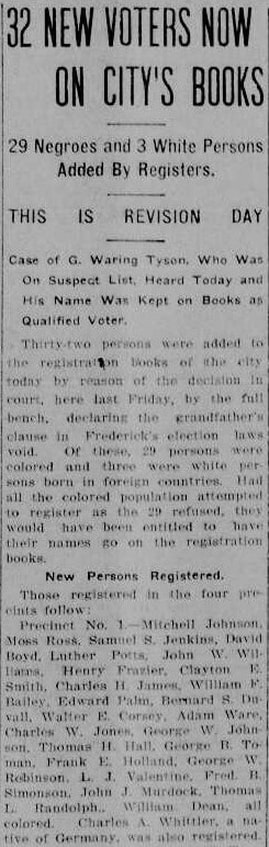

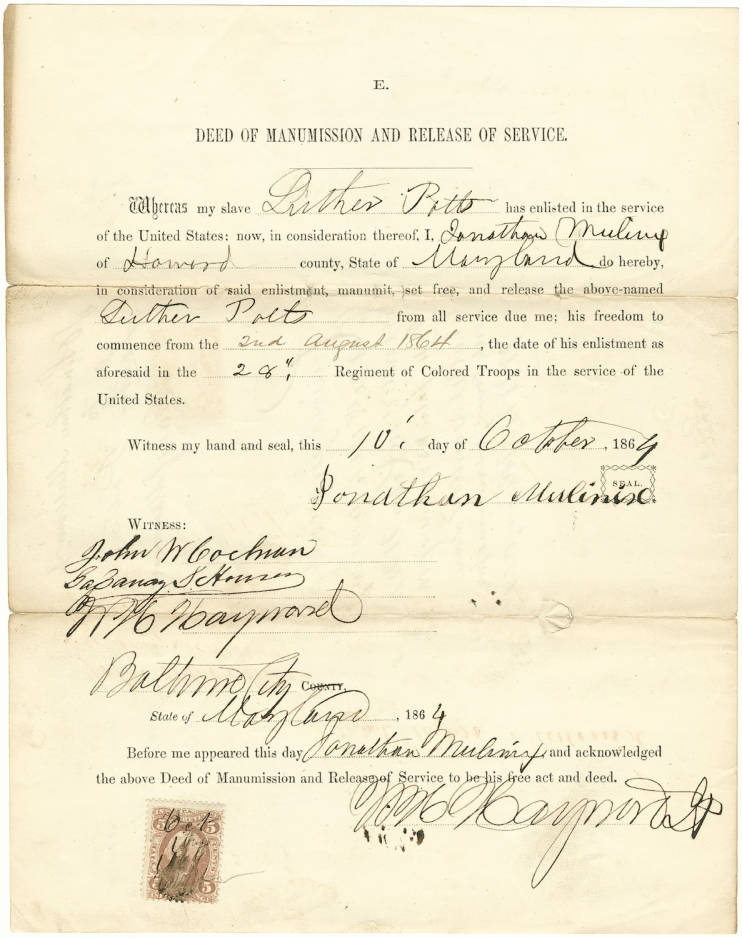

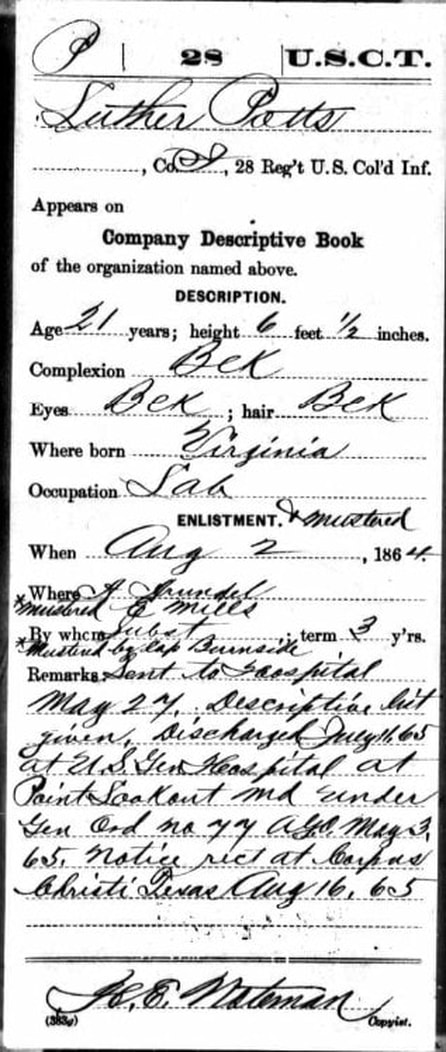

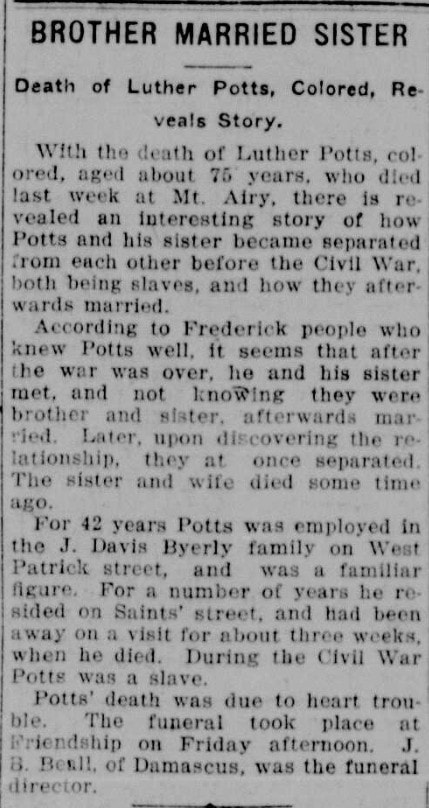

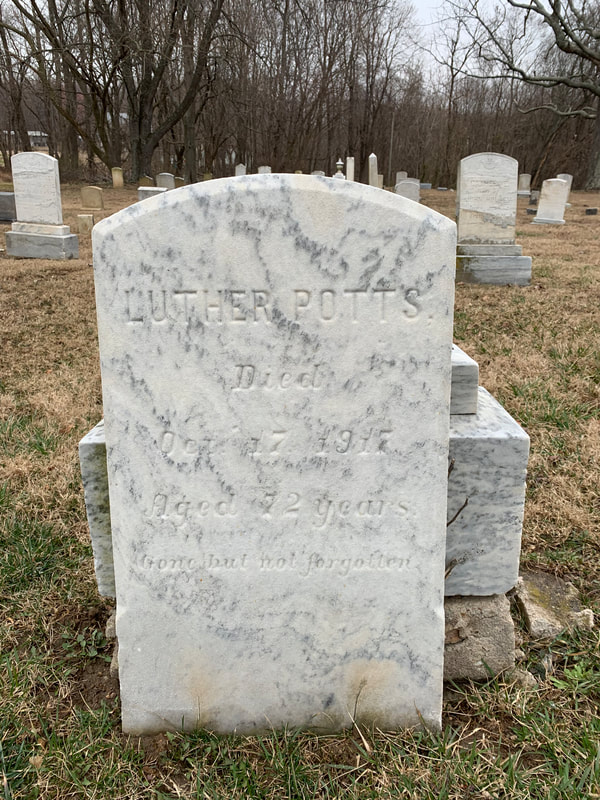

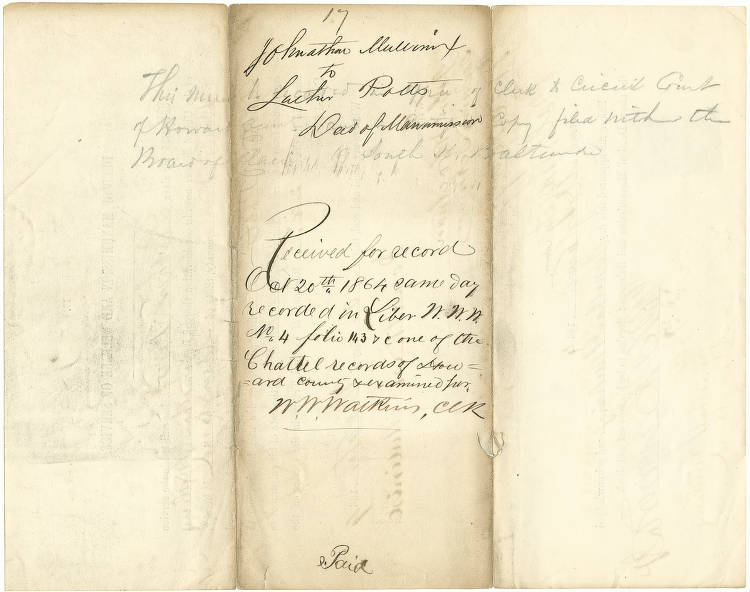

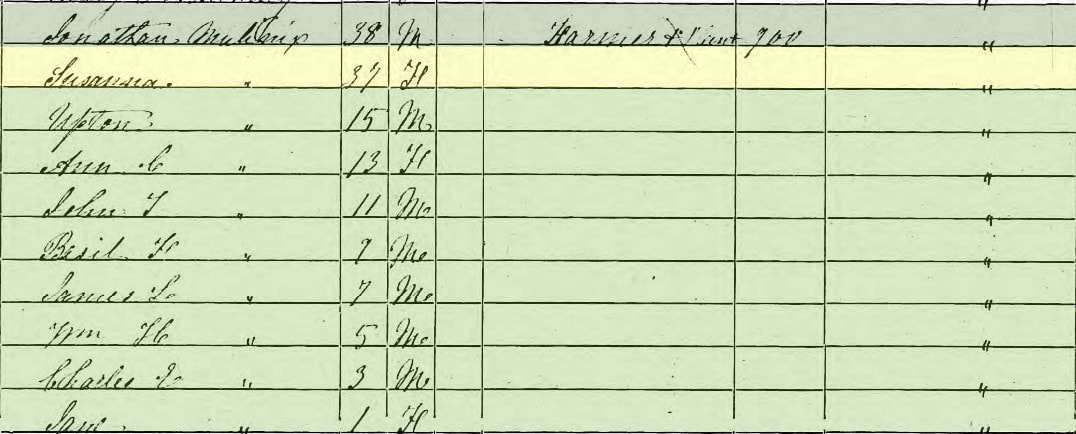

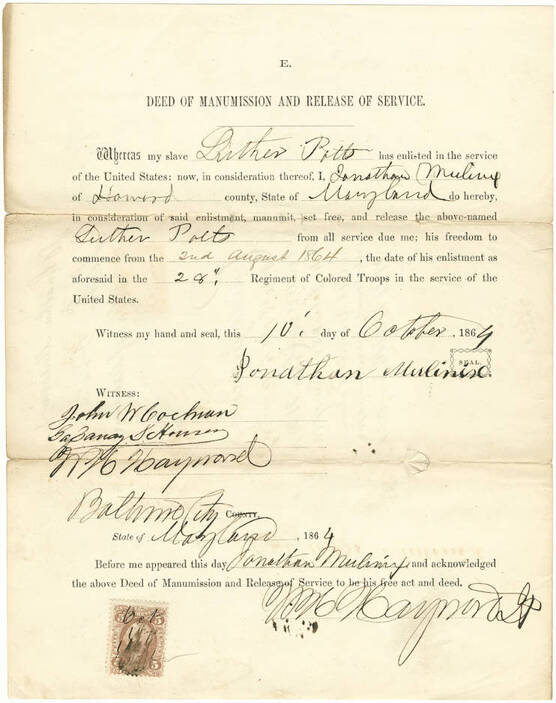

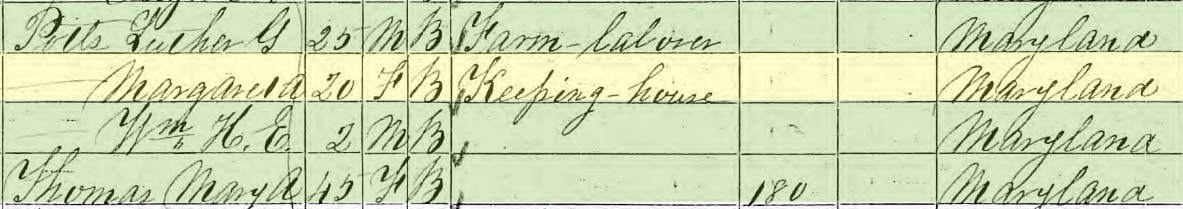

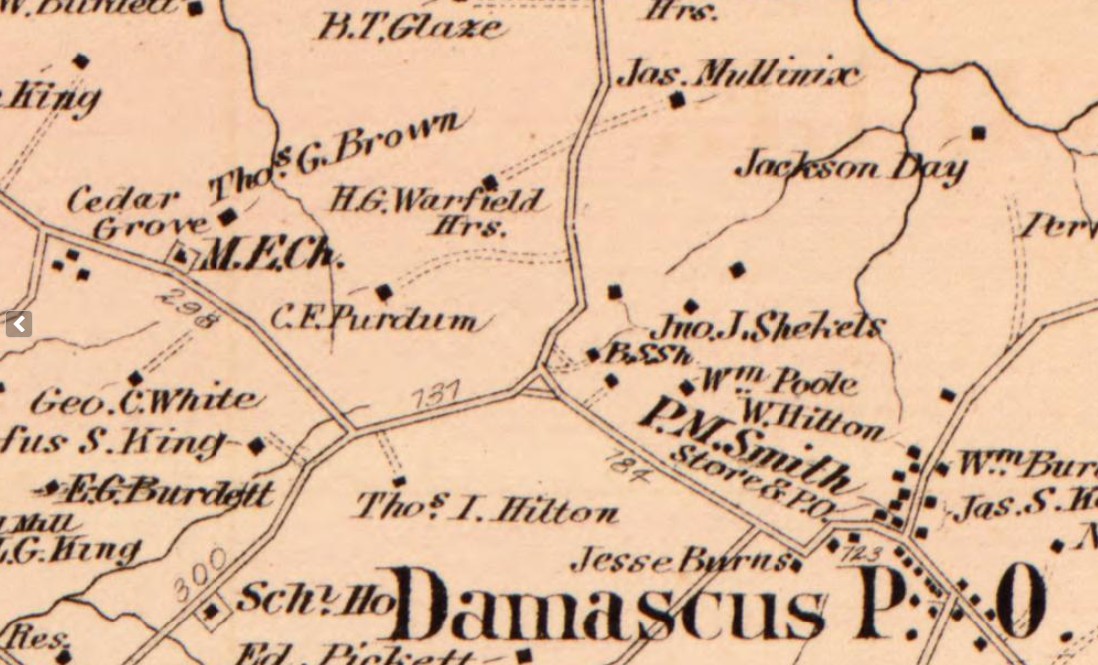

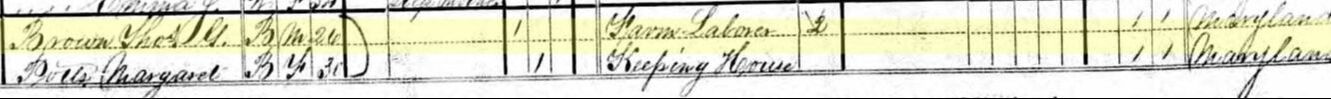

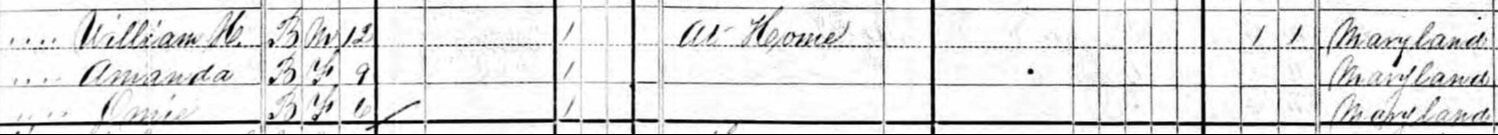

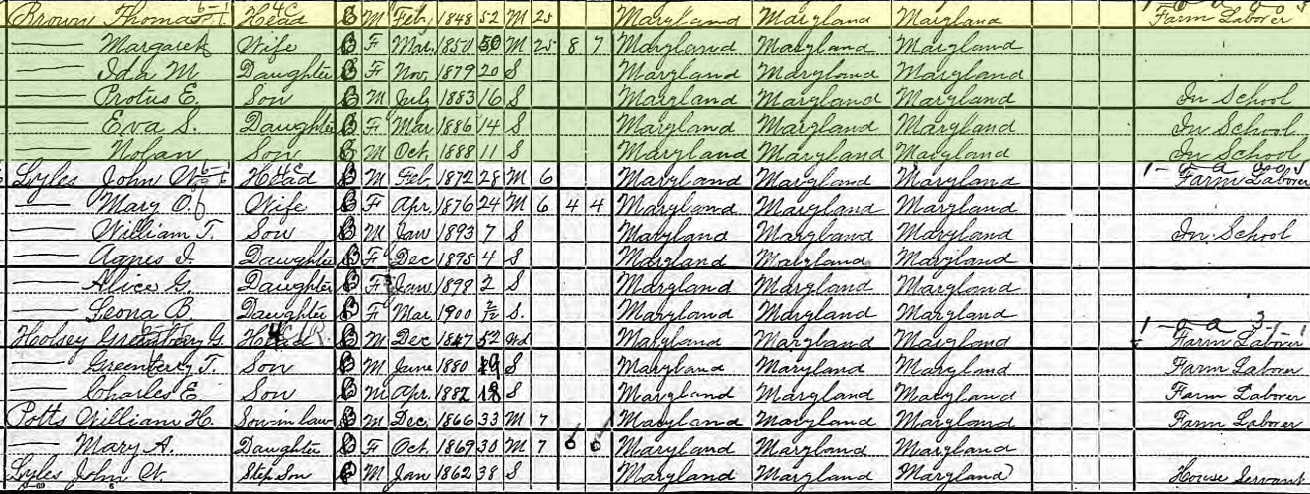

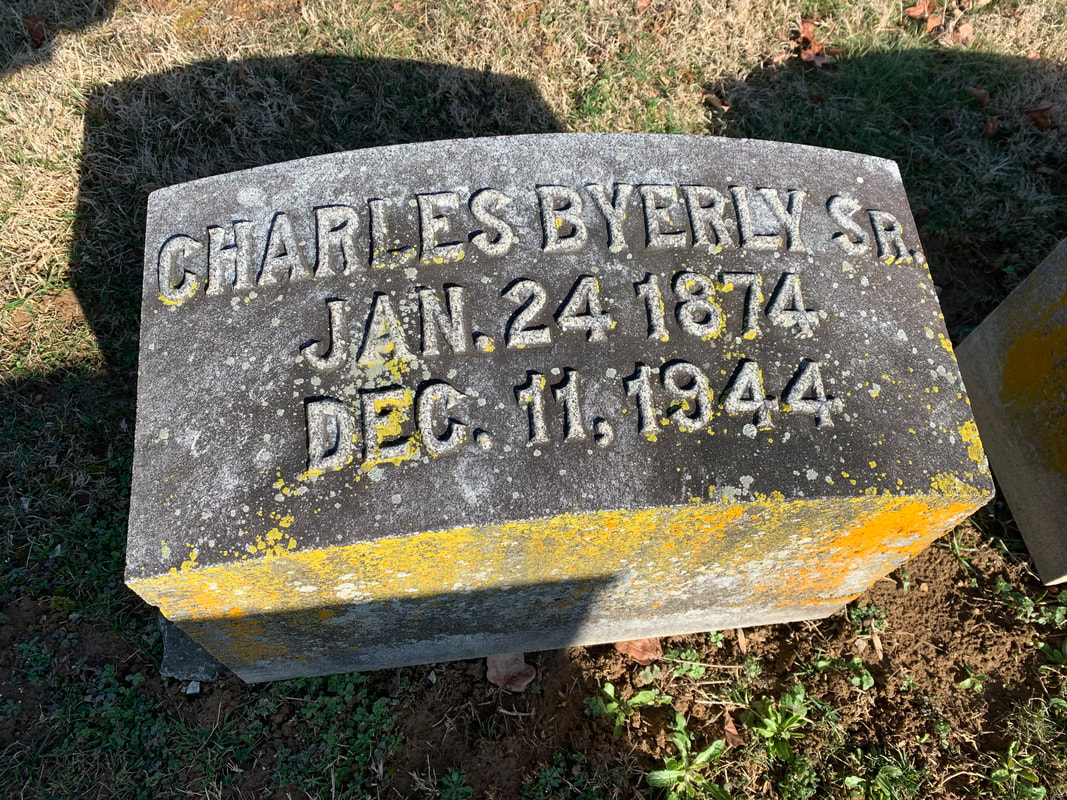

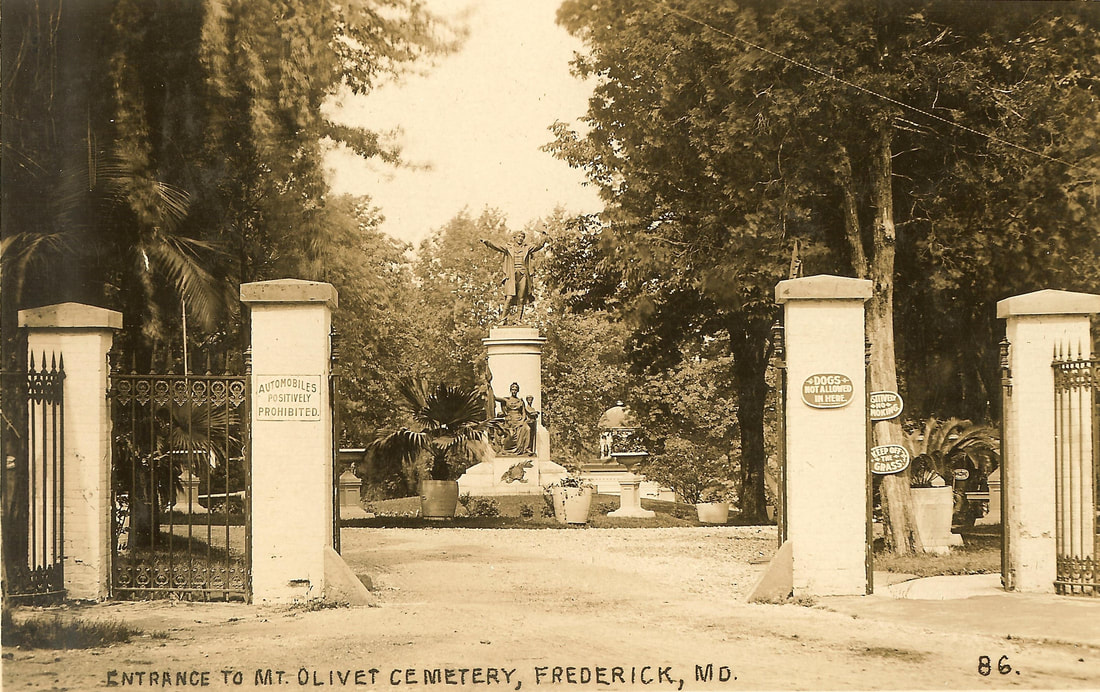

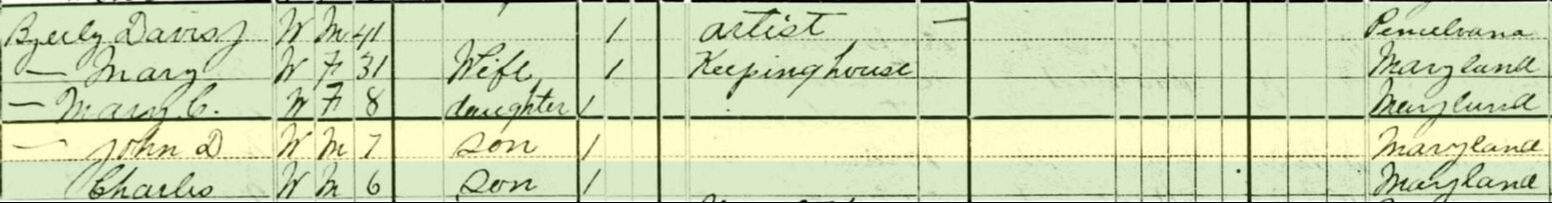

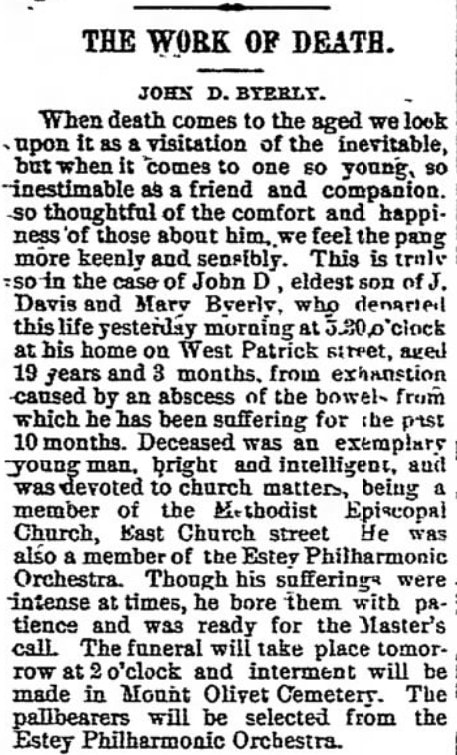

I truly can’t believe it’s been 25 years. Late February of 1998 was a very exciting time in my professional life as it marked the culmination of a documentary project that not only taught my local community a great deal about itself, but it had the same effect on me. The recipient of several local and national awards, this film afforded me the chance to travel to San Diego, California as the film had been nominated for a best documentary in the telecommunications industry. Subsequently, this work, which I titled Up From the Meadows: A History of Black Americans in Frederick County, Maryland won the Beacon Award of Excellence from CTAM—the Cable & Telecommunications Association for Marketing. The 5.5 hour video documentary originally aired the previous March (1996) on Cable Channel 10 of our local cable company of the era, GS Communications, which was co-owned with the Frederick News-Post by the Delaplaine and Randall families. While Cable 10 and GS Communications are memories now from Frederick’s past as well, the documentary (which was originally available on an equally ancient format called VHS) was remastered to dvd in 2014. It can still be purchased at the Frederick Visitor Center, and from time to time I am delighted to hear from new viewers who have stumbled upon it and learned from its rich content as I did while researching and writing it. The true magic comes from the the film’s amazing array of on-camera commentators and local historians. None of these people are still with us today, but their stories and words remain. As the title suggests, this program includes a comprehensive study of Blacks in Maryland’s largest county through the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. Established in 1748, our north-central environ of the state serves as an amazing case study to explore cultural history through the past 275 years, although I only covered 250 of it. The story continues. My central premise with this project was that Frederick represented “a border county within a border state” during the American Civil War. As a coincidence of geography, we were situated below the Mason-Dixon Line and Pennsylvania, loyal stalwart of the North, while being positioned directly above the Potomac River, the only thing dividing us from Virginia—home to Richmond, the former capital of the South. Of course, European settlement patterns dating from the mid-1700s helped dictate Frederick’s situation in regard to slavery (and non-slavery) up through the Civil War, and later would have a definitive influence on segregation until its abolishment with the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. As many know, German historically settled north and west of Frederick City, while many English and Scots-Irish settled south and east of our county seat. Of course there are plenty of anomalies, but the Germans followed a model of family farms, while many English and Scots-Irish employed the slave plantation model. In Frederick’s case, we had early French families who brought slave labor to the area as well. Again this is very generalized, as I invite you to watch the film if you have continued interest. This unique backstory helped me understand and explain events occurring here in Frederick throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. We had “brother vs brother/neighbor vs neighbor “ confrontations during the Civil War, and Frederick was a place of supposed “separate but equal” policies up through the 1960s which included restaurants, shops, theaters, and even Mount Olivet Cemetery as I wrote about in a three-part “Story in Stone” blog back in February-March of 2017. As I said at the time, I was very humbled to be in the position of making this film. As a 30-year-old white guy at the time of its debut, I served as nothing more than a conduit for several talented historians, researchers and former citizens who allowed me to share their stories and information. In 1997, the internet certainly did not afford the dissemination opportunities it does today, and the chance to make this documentary available to tens of thousands of people through our cable channel and VHS tape sales was more than worth the incredible amount of work and effort put into the project which boasted a shoestring budget and less than a handful of video production specialists. As I drive each day through the fore-mentioned Mount Olivet, I think of the Black residents of Frederick who have been buried within our gates today over the last five+ decades, and a small collection of folks I chronicled that died before the Civil Rights Movement and were interred or re-interred here anyway. One such could even be the long-lost daughter of President Thomas Jefferson and slave Sally Hemmings. I also think of the cemetery serving as the eternal resting place for Civil War soldiers from both sides, along with former slaveholders and local abolitionists. Along the lines of the latter group mentioned, we have two abolitionists to thank for the fame of our beloved Barbara Fritchie—author John Greenleaf Whittier of Massachusetts and E.D.E.N Southworth of Georgetown. Miss Southworth was the top-selling female novelist of the 1800s, and is credited with sending the “alleged” story of Dame Fritchie’s flag-waving heroics to Mr. Whittier. I could give you another history lesson here, but I will save it for another time. What I will say defiantly, is that this poem put Frederick “on the map” as they say, and filled readers’ heads worldwide with the vision of a sleepy little town characterized by its “clustered spires” framed against “the green-walled mountains of Maryland.” As many have already noticed, I borrowed my documentary title from the opening lines of Whittier’s Ballad of Barbara Fritchie: “Up from the meadows , rich with corn, Clear in the cool September morn.” I just thought it fit for so many reasons, as I recall explaining to Lord D. Nickens, one of my central mentors for the project. We were driving around the countryside near his former home in Flint Hill, southeast of Buckeystown, and he asked me what I planned calling this thing. He smiled, and said “I like it.” Now that I had a title, I needed to incorporate a brand which included a logo, color scheme and central image. The talented staff at the Frederick News-Post art department came up with a great logo and I had in hand what I thought to be the perfect vintage photo to use. When I started the project in late 1995, I relied heavily on the amazing collection of Frederick’s past, both housed and interpreted at the Frederick County Historical Society, today known as Heritage Frederick. The photograph and manuscript collection was not filled with a plethora of Black artifacts, but there were a few standout items. Among these was a vintage photograph that instantly struck me upon first sight. It was the photo of a young Black gentleman with a young child on his knee. The photograph dates from the late 1870s, and was taken by a local professional in his studio once located in the heart of downtown Frederick. Many have seen this image as it has appeared in other publications since my usage in the late 90s. Last fall, David J. Maloney, Jr. posted it on the Frederick Maryland Old Photos Facebook page. David is an expert when it comes to antique assessment and all things curatorial, and mentioned in his accompanying post that his offering was a glass plate scan from his own collection courtesy of Heritage Frederick. He described this image as “Portrait of a Black Man, Luther Potts, and John Francis Byerly (son of the photographer).” David pointed out the prominent presence of agricultural implements in the hands of both subjects and went further to include a close-up view of the bottom of the photo pointing out that Luther’s clothing shows evidence of wear. At their feet is an assortment of props including a child’s wagon and wheelbarrow. There is also a horse drawn toy wagon marked “HARD & SOFT COAL/COKE AND KINDLINGS/COAL.” Upon my first viewing of this photograph at the Historical Society back in 1996, I was unsure of the race of the child, thinking perhaps it could be a mixed-race child. I soon read the description attached to the Society’s collection which confirmed for me the young boy as being white as I was already familiar with the Byerly family of photographers. In 2007, Mark Hudson, former director of the Historical Society of Frederick County, worked with staff and volunteers to produce a few brown-book pictorial histories under the title of Frederick County and Frederick County Revisited under Arcadia Publishing’s Images of America series. On page 113 of the second book, one can find the photograph in question, with a more detailed caption: "John Francis Byerly took this photograph of his son, Charles, and Luther Potts, the family’s handyman, about 1880. Potts was an organizer against Frederick’s registration law in the 1913 municipal election. The law required that only those males who owned more than $500 worth of property and were eligible to vote, or were male descendants of someone who was eligible to vote, in a state election before January 1, 1869, could register. The law was aimed directly at the local Black community. It was challenged in court, and pending a decision, Potts and about 30 others tried to register but were refused because of the “grandfather clause.” They believed that the law was in conflict with the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution; city attorneys claimed that the amendment regarded only federal elections. On May 16, county judges disagreed and declared both clauses unconstitutional." I wanted to learn a bit more about these two photograph subjects, and readily assumed that I would likely not find Luther Potts here in Mount Olivet due to our past history of burial. Interestingly, we have many people of that surname interred here and even a special gated lot in Area G, which holds the relatives of former early congressman Richard Potts. In contrast to Luther, I easily located the final resting place of the younger subject, and his photographer father, just 20 yards to the south of the Potts Family Lot, and along the central drive that passes by both. I will start with just a few things I could find through Ancestry.com and local papers on Luther Potts. He appears in the 1910 US Census living in Frederick at 65 years of age. This dictates that he was born roughly 1845, which would make him around 35 in the Byerly photograph. In the 1910 census, his listed occupation was that of odd jobs which seems to match that of having served as a handyman for the Byerly family at that 1880 time period. I could not find Luther Potts in another local census at first, however I did locate a Lewis Potts in the 1850 census. Lewis and Sarah Potts lived in Frederick City at the time and had children, one under the named Charles who was listed as being five years old at the time. This matches our Luther's approximate 1845 birthdate, however the name is nowhere close. Back to the drawing board, but maybe these folks are relatives of some sort? I found a couple of newspaper articles mentioning Luther from the 1879 and 1887, but these do not showcase Luther in a positive light. On the other hand, I did find some articles from 1913 to back up the claims of Luther’s role as an organizer against Frederick’s unjust voter registration law. The last two remaining tidbits, I uncovered through my quick research, may provide clues to Luther’s whereabouts during (and before) the American Civil War. I found an interesting document for a Luther Potts of Howard County who was released from bondage to join the Union Army’s 28th Regiment of Colored Troops. Could this be our Luther? Although, I could not locate a traditional obituary for Luther Potts, I did learn of his death in the fall of 1917 courtesy of an odd news story which appeared in both Frederick and Westminster newspapers. It claimed that Luther was a former slave, and confirmed Luther’s employment relationship with the Byerly family. His home was also addressed as having been on All Saints Street, however he had some sort of connection to Mount Airy, and also the Damascus area of Montgomery County, as his final resting place would be in a small hamlet called Friendship (about two miles north of Damascus on MD 27). I found Luther’s gravestone in the Friendship Methodist Church Cemetery along Ridge Road (MD27) with a death date of October 17th, 1917 (age 72). I was inspired this past weekend to visit the gravesite of the man who has graced my documentary cover for the last 25 years. Unfortunately, his tombstone needs to be placed back up on its pedestal, but it looked as if it had been recently been cleaned. While at the graveyard, I also found other folks holding the last name of Potts as well: Potts, Amelia, d. Mar 11 1917, age 65yr 3mo Potts, Caleb G., d. Dec 10 1922, age 46yr 8mo 15da Potts, Caleb, d. Jul 21 1916, age 77yr John Henry Potts (1870-1946) unmarked grave Joseph Washington Potts (1883-1959) unmarked grave Potts, Lillian M., b. Jun 4 1892, d. Dec 24 1940, age 58 years Potts, Margaret, d. Oct 25 1906, age 60 years Potts, Mary E., b. 1872, d. 1947 Potts, William E., b. 1867, d. 1945 In doing a little more sleuthing, I learned more about Friendship, and a nearby slave plantation that likely held the answer to Luther’s days as a slave, and also his manumission. Jonathan Mullinix (1811-1899) was very wealthy man who owned an enormous amount of property and slaves in northeastern Montgomery County near the county line with Howard County. Friendship is located to the south of Clagettsville (where Kemptown Road (MD80) and Ridge Road (MD27) converge. Named for Friendship, the farm to the north, it had its origins as a Black community. One of its earliest dwellings, perhaps with roots dating to the 1830s, is the Inez Zeigler McAbee House on Holsey Road. Tradition holds that this dwelling was built on land conveyed in 1835 to John Holsey, a Black farmer, by the Mullinix family, The Holseys and other Black families who settled in the vicinity were former slaves on the Mullinix plantation named Long Corner, among other Mullinix properties in the area.  Section of the 1879 Bond Atlas Map of Montgomery County showing plenty of Mullinix farms (Mullineaux) in the vicinity east of Damascus. Friendship Cemetery is on the road between Damascus and Clagettsville and below the Jno. H. Clagett residence on this atlas but not in existence at the time of this map. I immediately flashed back to the Civil War record for Luther I had found. The witness who had signed it was Jonathan Mullinix. This explains why Luther enlisted in Howard County. As a matter of fact, Luther was manumitted so he could serve. Another military record shows that Luther was listed as a substitute. I think it is highly likely that he took the place of one of Mr. Mullinix’ sons. Speaking of the Civil War, I found that Luther’s brother, Caleb Potts, Sr. served in the USCT as well. He lived in the Mount Airy-Woodville area. Luther was likely visiting Caleb’s son at the time of his death, his brother having died the previous year. He is buried only a few yards behind Luther at Friendship. Most interesting was the discovery of Margaret Potts. Her final resting place was positioned in the northwest extreme of the small burying ground that extends to the side of route 27. Her stone seems as if it were not in the right place as it faced east while most other stones here faced west. It was oddly placed away from the pack as well. Had it been moved? So just who was Margaret you may ask? Well, I searched for her on Ancestry.com and made an incredible discovery. In the 1870 US Census, she can be found living in Friendship. More interesting is that she was living with Luther as his wife. The couple had a 2-year-old son also listed , William H. E. Potts. If we are to believe the article that appeared in local papers at the time of Luther’s death in 1917, Margaret was Luther’s sister and also his wife. I found Margaret again in the 1880 Census, but Luther was not living with her. However, housemates included son William and two other children—Amanda and Omie. The head of household listed was a Thomas G. Brown. I found his name, and the location of this dwelling a mile west of the cemetery, on the Bond Atlas of 1879. That little graveyard at Friendship held the graves of a few of Luther's children and I just kept thinking of Luther holding each on his knee, as he had done with the Byerly child in the famous photograph. The Byerlys This is a family that I have been planning to write a “Story in Stone” on since this blog’s inception in fall of 2016. I will go in-depth with a “part II” of sorts next week. For now, I’d like to stick with our Black History focus and the image of Luther Potts captured by the camera of long-time Frederick photographer John Davis Byerly (1839-1914). I will give a brief prelude by saying that John Davis Byerly was the son of Jacob Byerly (1807-1885), founder of Frederick’s first photographic studio in 1842. J. “Davis” Byerly took over the family business upon his father’s retirement in 1869, and is credited with so many well-known vintage images in, and around, Frederick during the late 1800s, before turning over the firm to his son Charles. The latter continued making incredible photographs of Frederick’s people and places, including several iconic photographs of Mount Olivet Cemetery in the early 1900s. So, is Charles the young boy in the photograph with Luther Potts as reported in the Frederick County Revisited book of 2007? Or is it John Francis Byerly as David Maloney added to his Facebook post this past fall of 2022 on the Old Frederick Photos Facebook page? Either way, both gentlemen are buried in the Byerly family lot in our cemetery in Area G/Lot 36 and 37, along with father J. Davis Byerly. There is one glaring problem however. John Francis Byerly is definitively not the name of the child in this photograph that has been dated to c. 1880. That’s because John Francis Byerly was the name of a son of Charles Byerly, and would not even be born until 1904. This was not a typo or error by Mr. Maloney, as it simply goes back to an error that is attached to the record of the photograph in the files of the old Historical Society of Frederick County. And here is that record from Heritage Frederick’s extensive archive: Black Man (Luther Potts) and Child (John Francis Byerly) Photo taken in studio of young black man and child in his lap. Farming tools and toys. [Mrs. Howard Kelly, in an interview at the Historical Society in 1998, identified the little boy as John Francis Byerly, son of Charles Byerly (b. 1874). She further identifies the man in the picture as Luther Potts who was a gardener or handy man who worked for the Byerlys. She did not know anything else about Luther.] And there you have it, all is fine until some meddling, cemetery historian comes along and spoils the party. I have to say, that I see now that I, myself, could have been the cause of the problem solely by my interest and use of this photo for my documentary in 1997. Perhaps that curiosity led to the 1998 interview with Mary Elizabeth Kelly who passed away in 2006 at the age of 94. She was the daughter of Mary Catherine Byerly (1871-1937), a daughter of photographer J. “Davis” Byerly, and sister to Charles. This would make John Francis Byerly a first cousin to Mrs. Kelly. That leads me back to the family of John Davis Byerly. Since the photo at hand was said to have been taken in 1880, let’s simply look at the 1880 US census for guidance, shall we. Davis and Mary have three children, the aforementioned Charles, Mary Catherine and one more, John Davis Byerly, (Jr.). That’s it, error solved, did Mrs. Kelly mean to say John Davis Byerly instead of John Francis Byerly? She was 86 when the interview was conducted, and certainly a forgivable mistake—more impressive was her identification of Luther Potts. John Davis Byerly (Jr.). was born on August 25th, 1872. He was the middle child of Davis’ children, but just a year and a half older than brother Charles. This photo was likely taken a few years before 1880, because the young boy seems to be about four or five in my estimation. So now we have a conundrum on our hands—W as it John Davis (Jr.) or Charles sitting on Luther’s knee? We may never know, but for Mrs. Kelly to bring up John’s name instead of Charles, I would go with the old expression, “Where there’s smoke, there’s fire.” I’m leaning toward John Davis Byerly (Jr.). Now I have one more opportunity for those among you who want to employ a facial analysis study. Mrs. Kelly provided several family photos for Gorsline, Whitmore and Cannon’s Pictorial History of Frederick—a must have for every Frederick history lover. One such photograph within this work (first published in 1995) is a family group photo including the Byerly and Markell families taken in the courtyard of the Byerly residence at 110 West Patrick Street. It was “snapped” in the year 1891 at the stately town home that sadly no longer exists, as it is now the site of the Frederick County Courthouse outside plaza area. My initial thought was “Who took this photo?” as all the professionals are within the shot. Interesting people of note here include J. Davis Byerly (Third Row extreme left with beard and moustache); Charles Byerly (Second Row extreme left); Mary Markell Byerly (second row to the immediate right of Charles); John Davis Byerly (Jr.) (second row extreme right); and Mary (Byerly) Chapline (front row, second from right in black and white dress and elbow on her grandfather George Markell’s knee). Take a look at the faces of both brothers, Charles and John Davis, and compare to the kid in the photo with Luther, and tell me what you think. As I said earlier, they are buried next to their parents on Area G/Lot 36-37, only a few yards south of the Potts Lot along our central driveway through the cemetery. I will talk more about Charles in our next installment, however, I want to bring up the fact that John Davis Byerly (Jr.) would pass not long after the family photo above was taken. He spent most of the year battling a painful malady, requiring frequent treatments in Baltimore. His death occurred on November 29th, 1891.

I will wrap this up this “Story in Stone” with another fascinating Byerly photograph from the archives of Heritage Frederick. This was also featured in the Frederick County Revisited publication with a caption that reads as follows:

“This photograph was taken by Charles Byerly about 1905 at his brother’s Mount Olivet Cemetery grave site. John D. Byerly died in 1891, at ager 19. While the photograph today may seem a bit odd, it would not have been when it was produced. At the time, public cemeteries, with their mixture of natural and monumental, were considered pleasant and respectable places for picnics and and other informal gatherings.”

2 Comments

Jacquelyn M Ebersole

3/4/2023 03:22:06 pm

Please include me in any of your writings. I live In Rosemont but am on the Brunswick Historic Commission. I am a Master Docent and have volunteered for a very long time at the Brunswick Heritage Museum, working with the photographs on several projects. I really enjoy your writings.

Reply

Kristi Edens

4/5/2023 05:44:49 pm

Sorry, somehow I missed this story when it first came out. Awhile ago, you published a story about my 4th great-grandfather, Frank Miller, and his swim accross the Potomac to stop Lee's army. Interestingly, my grandfather Frank Depro, the other Frank's great-grandson, was the minister at Damascus Methodist from the early sixties, but since Friendship didn't have a full time minister, my grandfather would preach there occasionally when I was a little girl..

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed