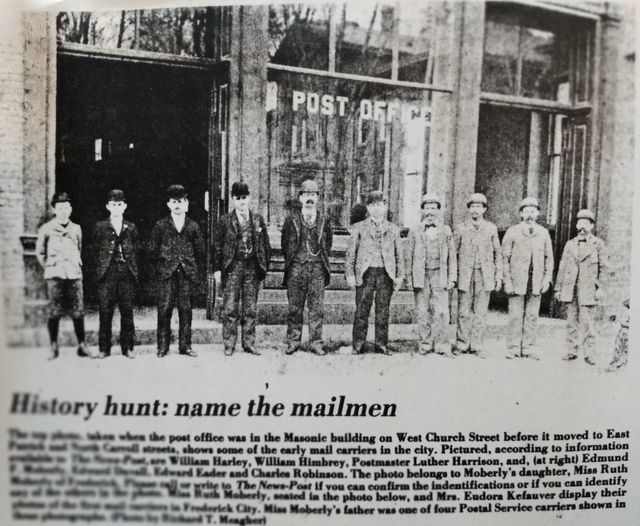

|

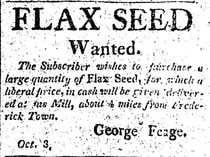

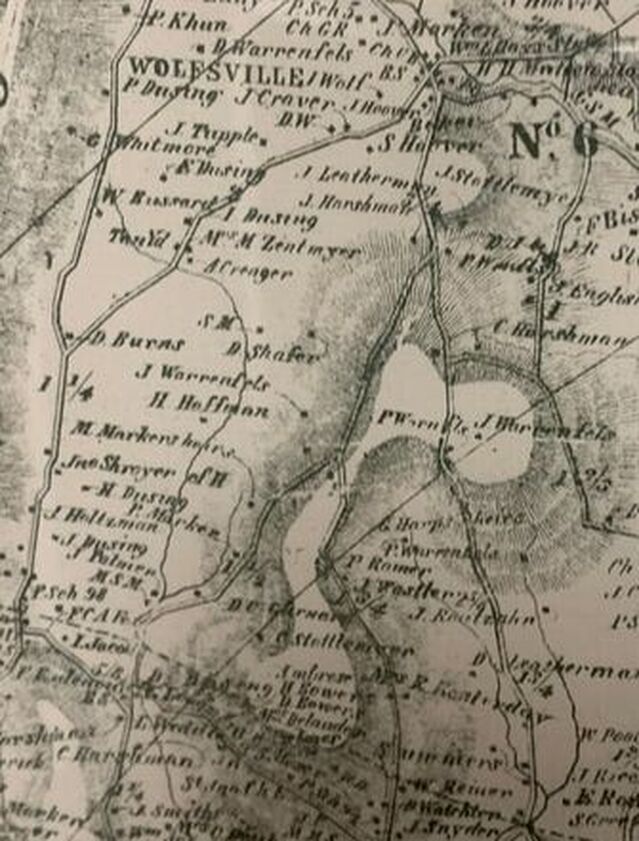

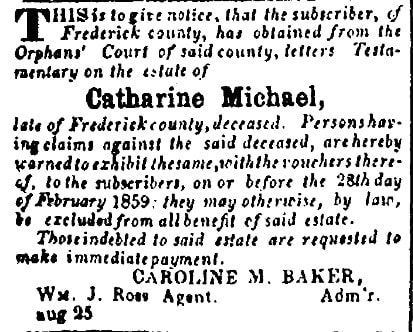

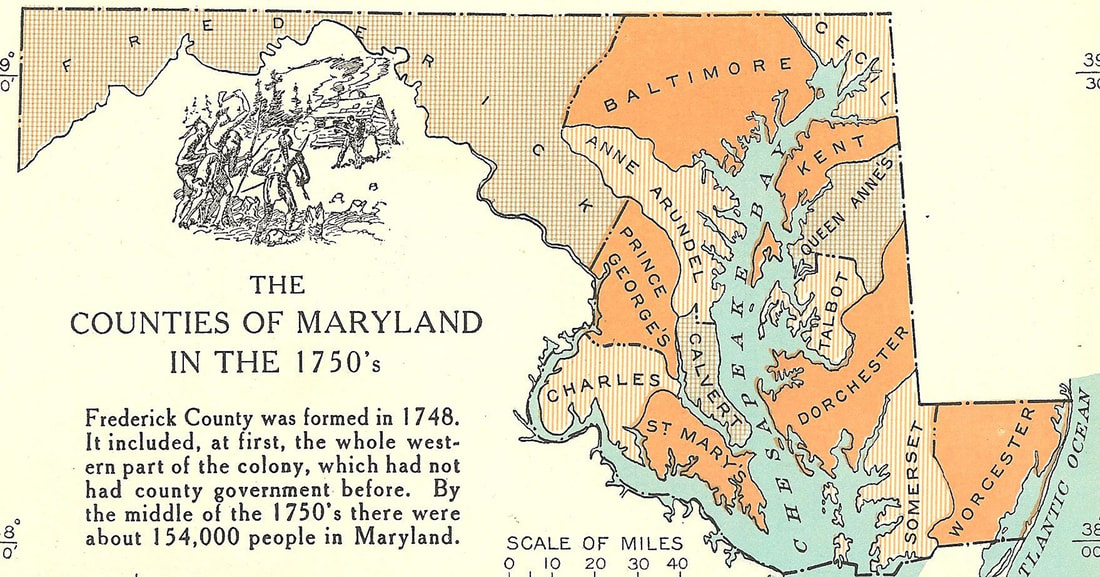

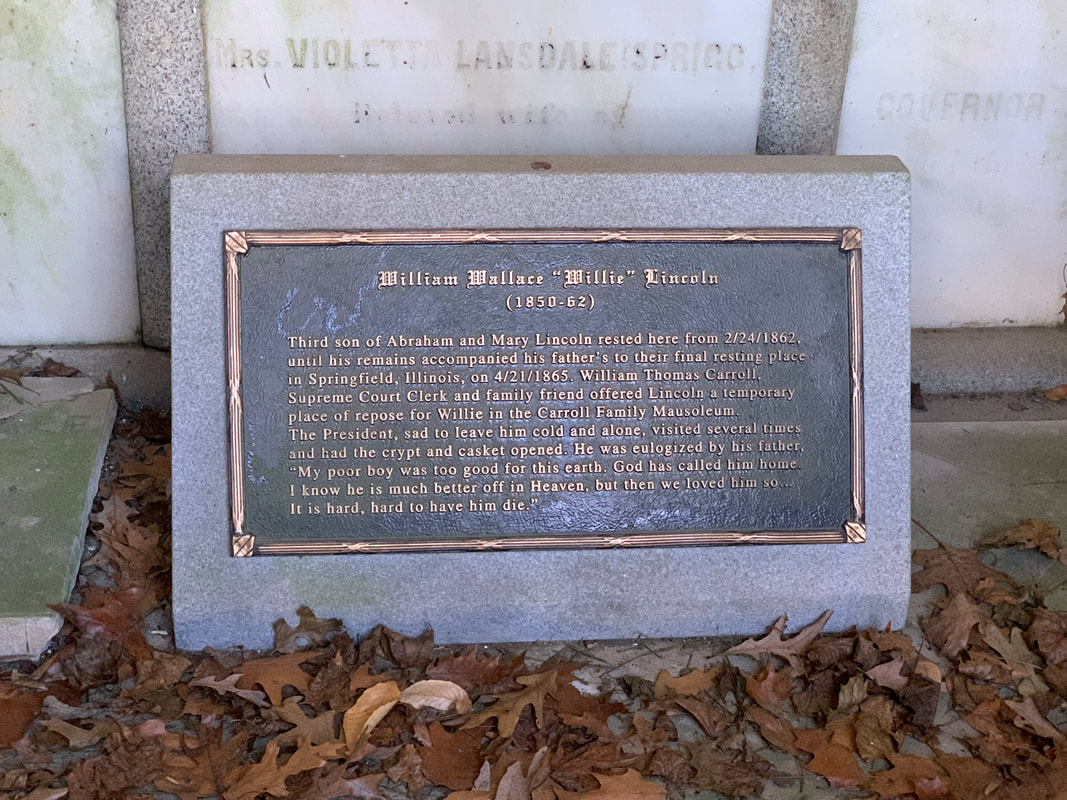

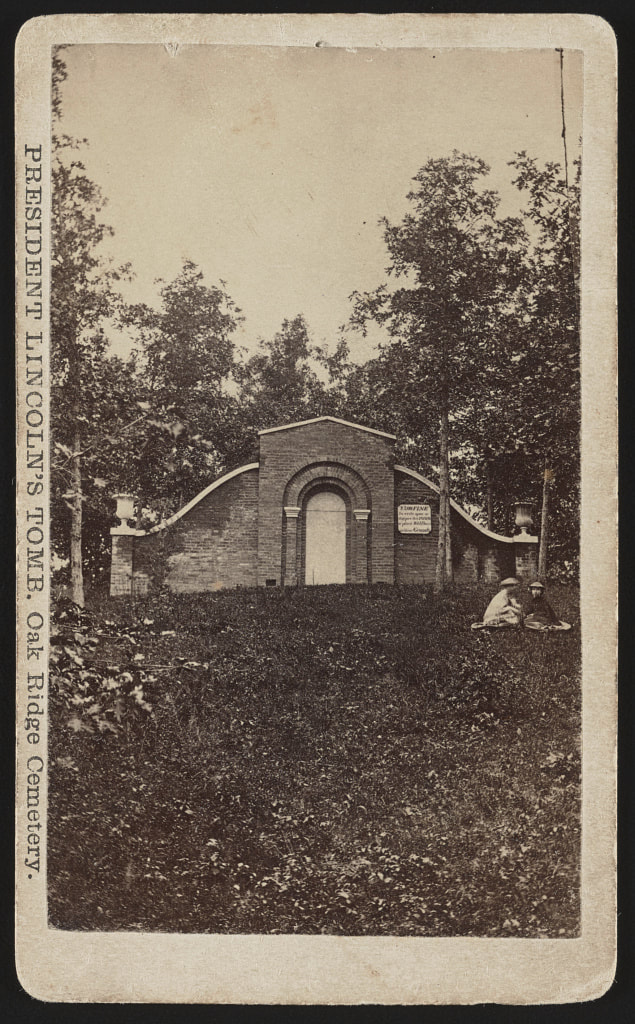

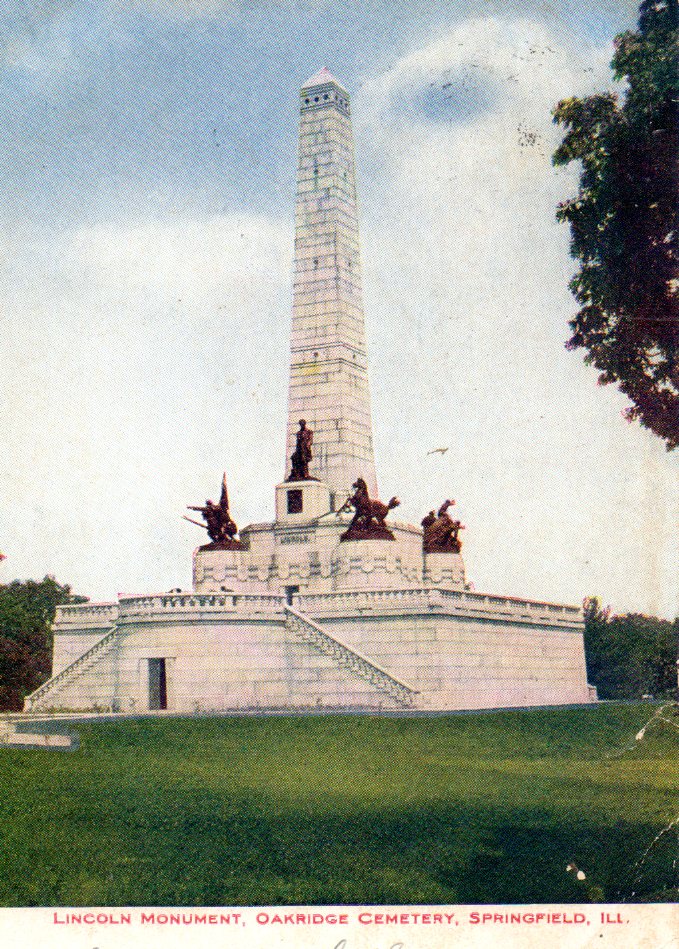

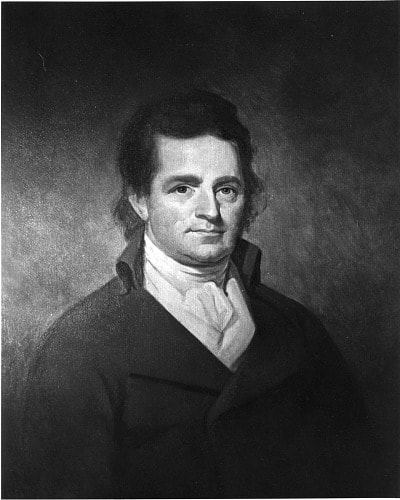

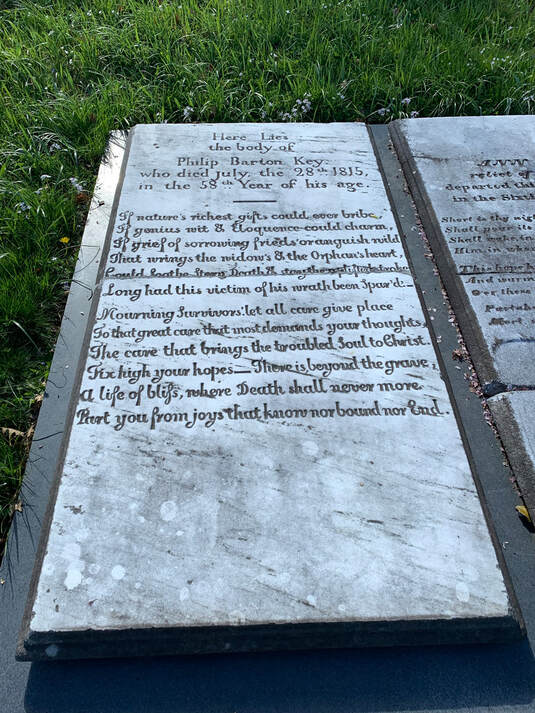

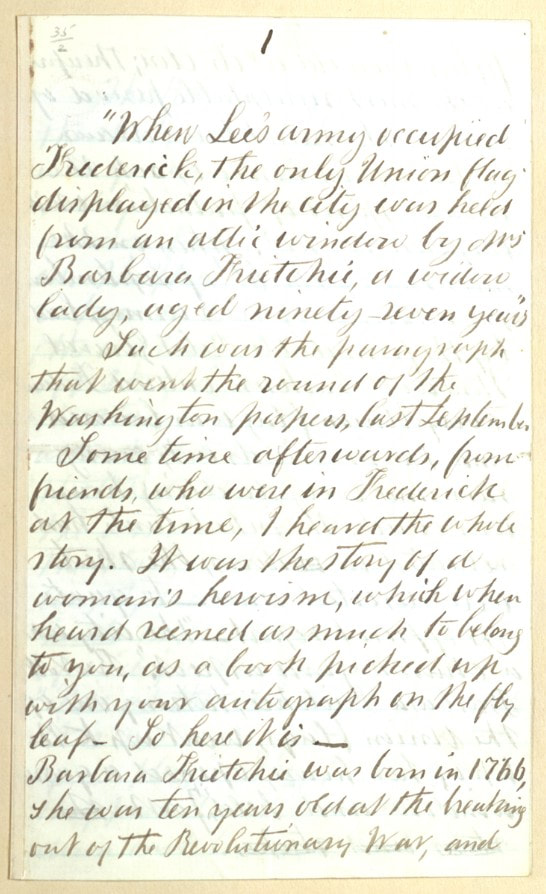

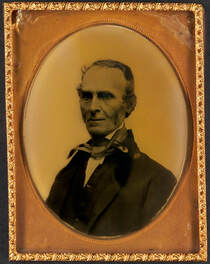

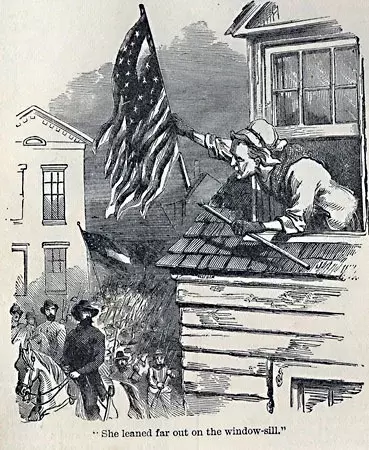

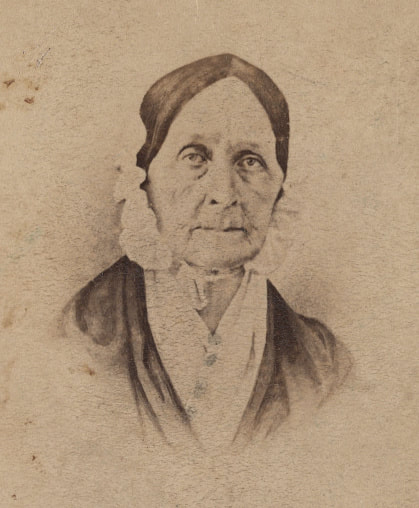

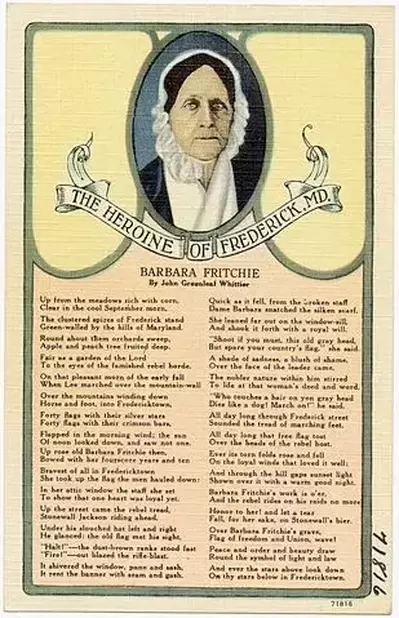

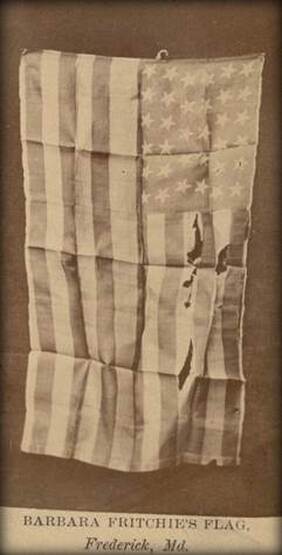

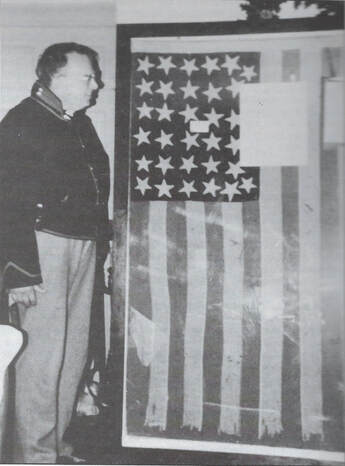

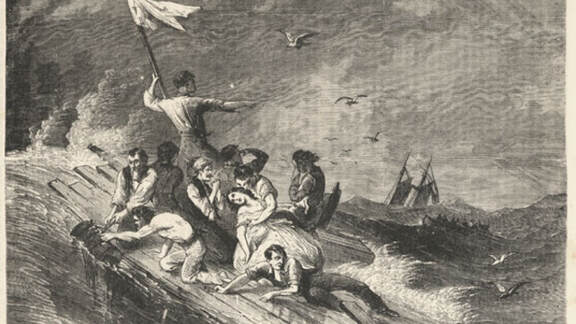

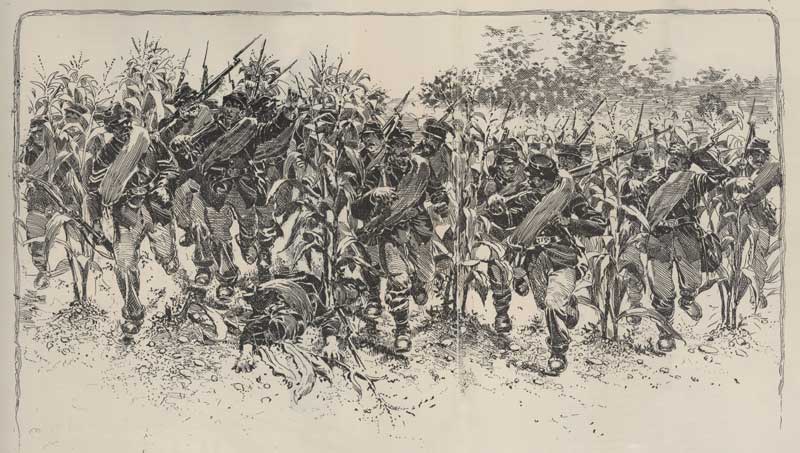

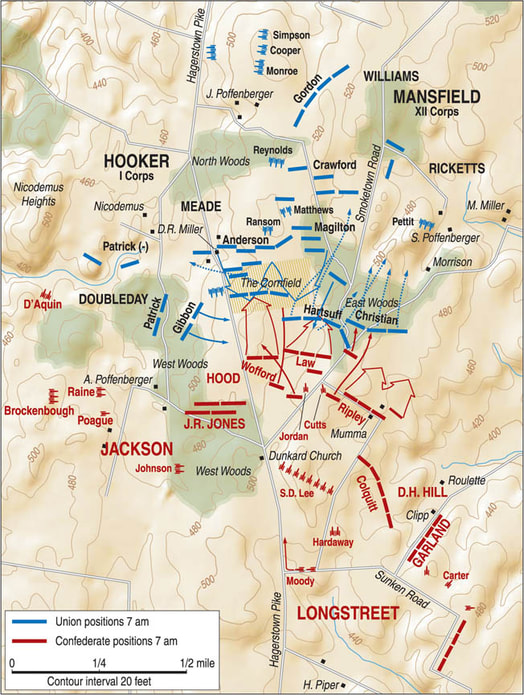

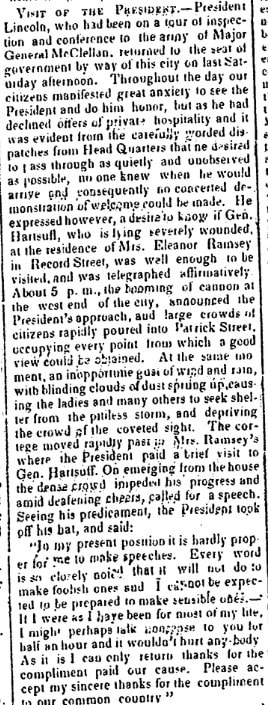

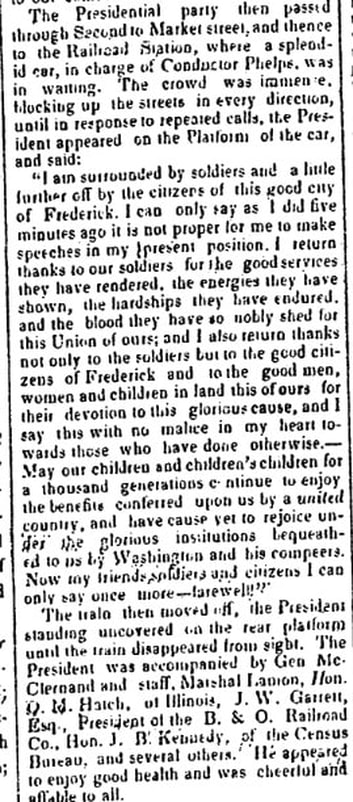

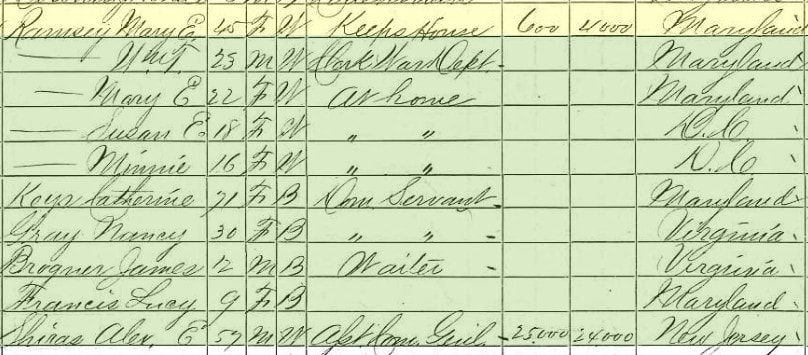

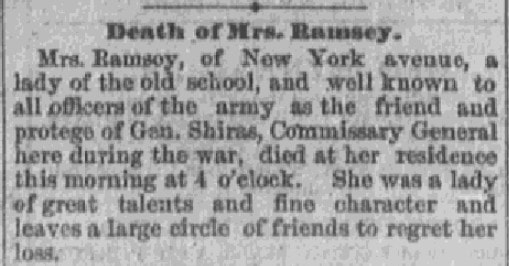

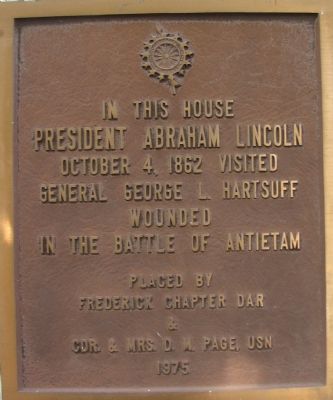

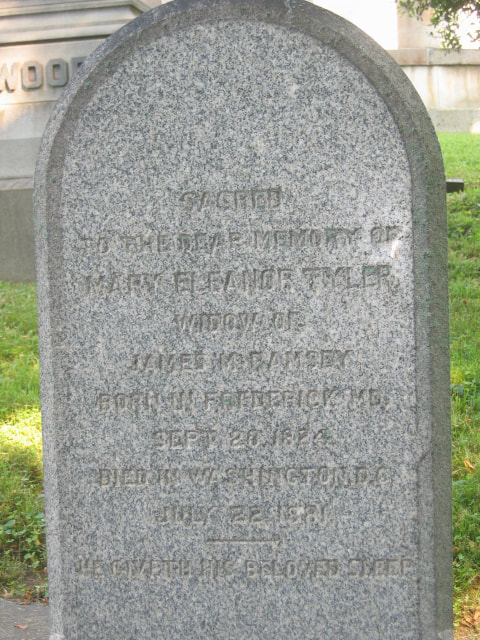

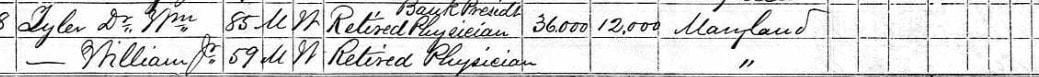

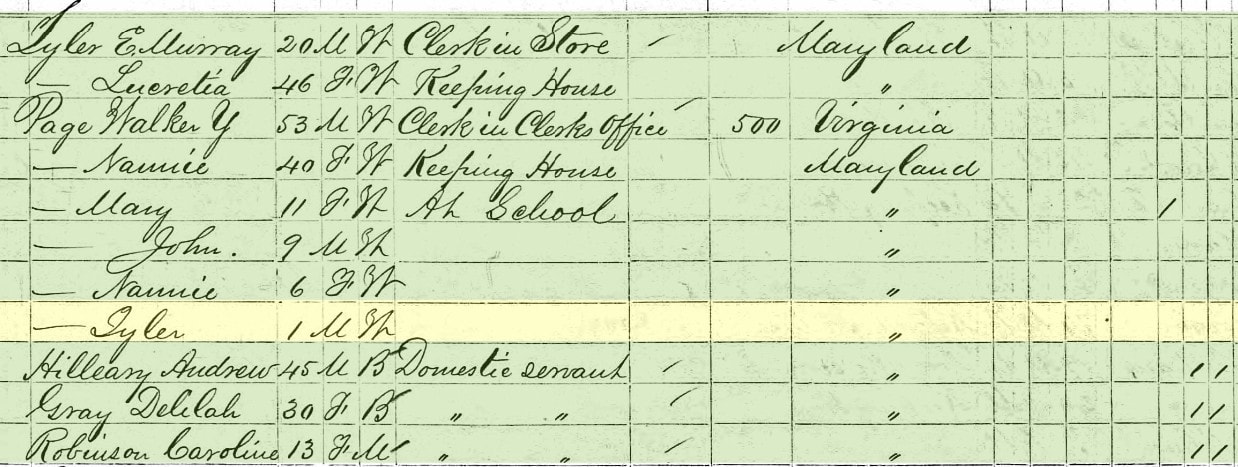

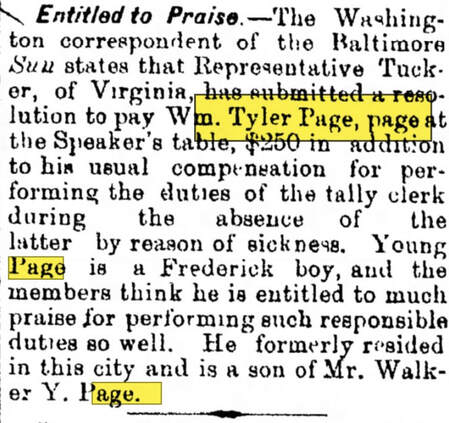

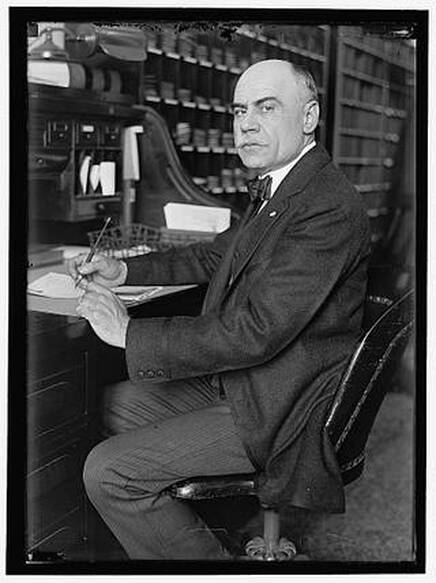

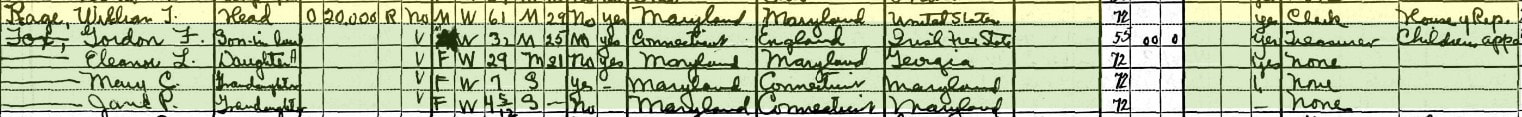

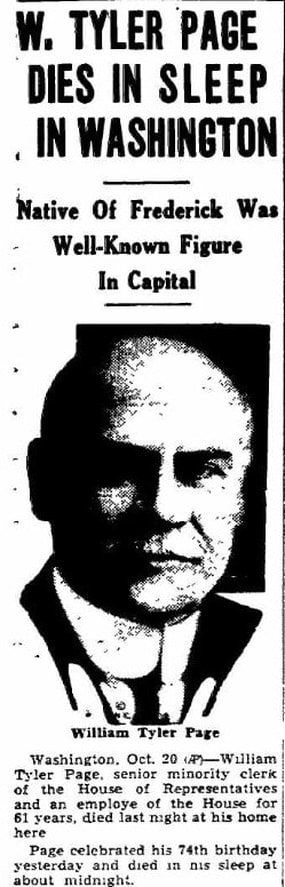

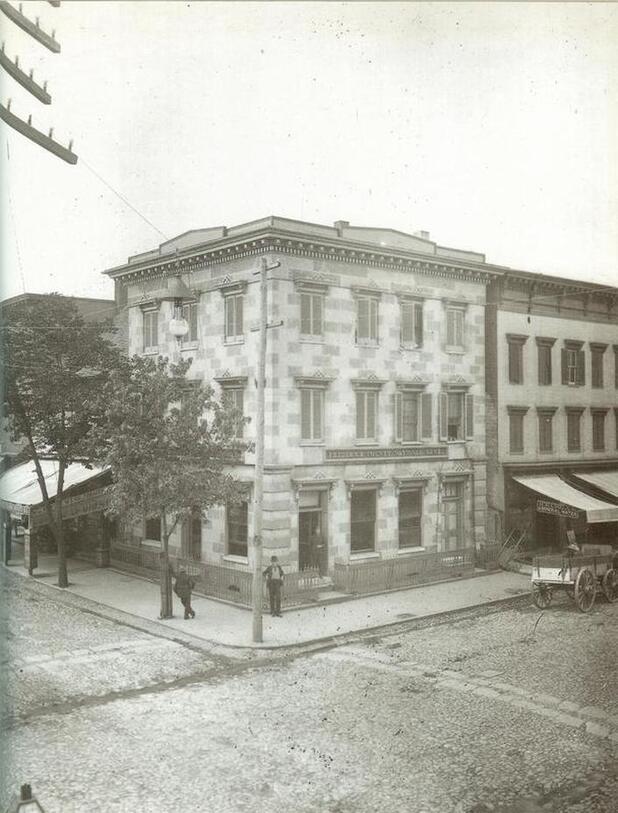

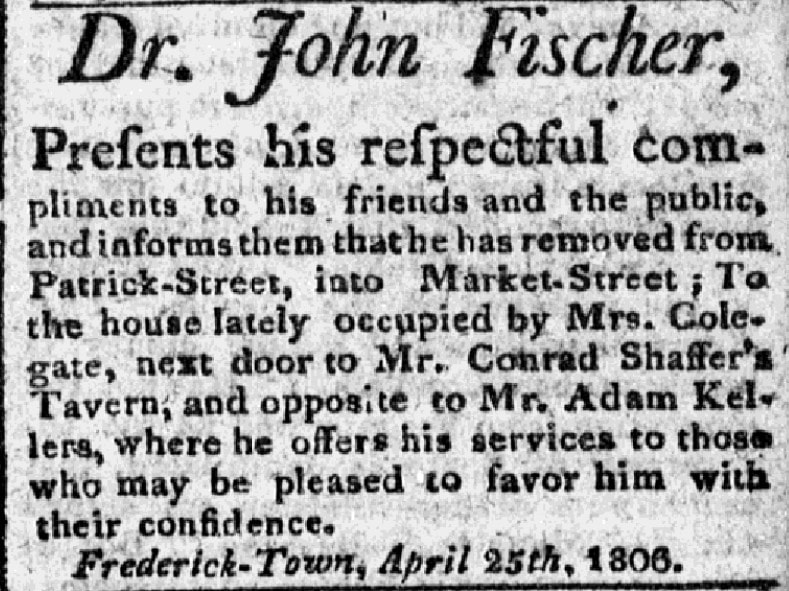

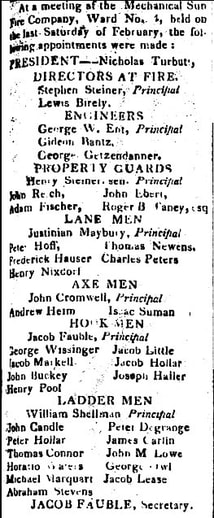

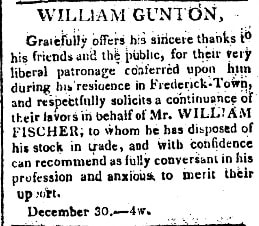

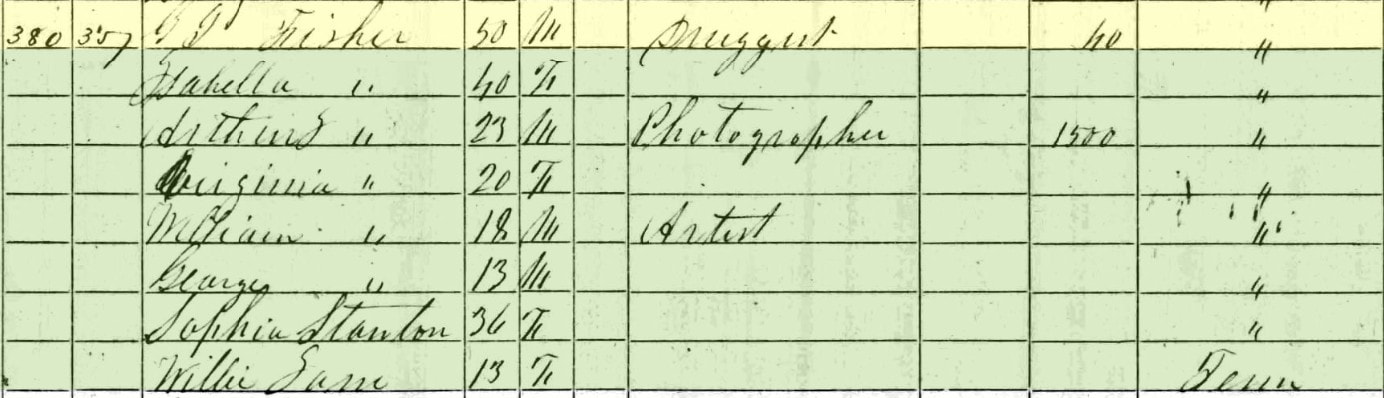

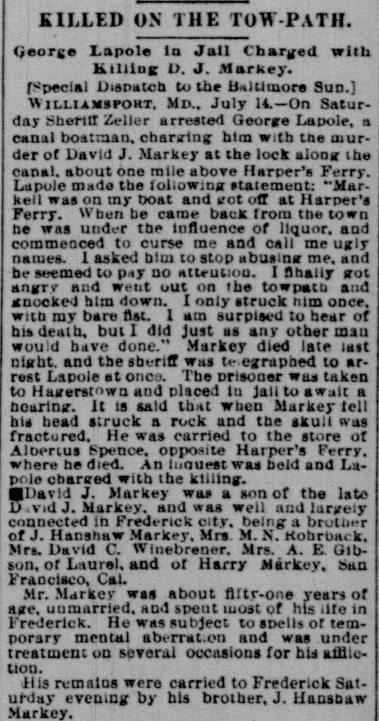

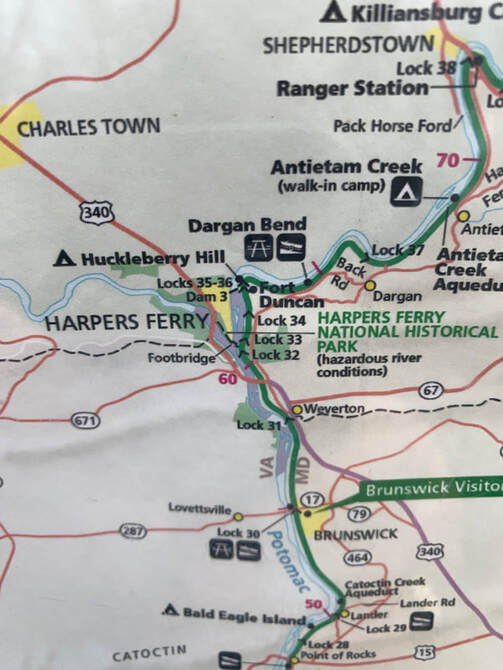

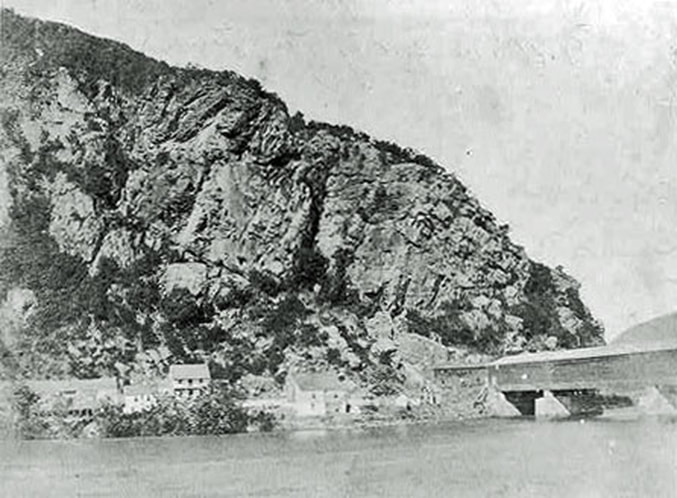

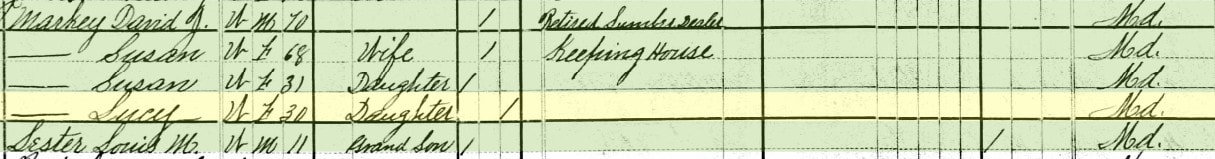

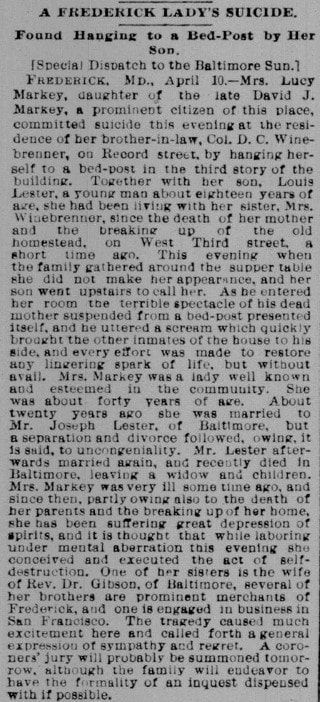

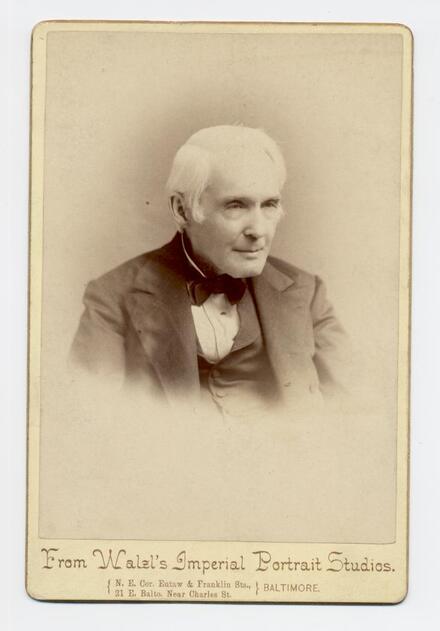

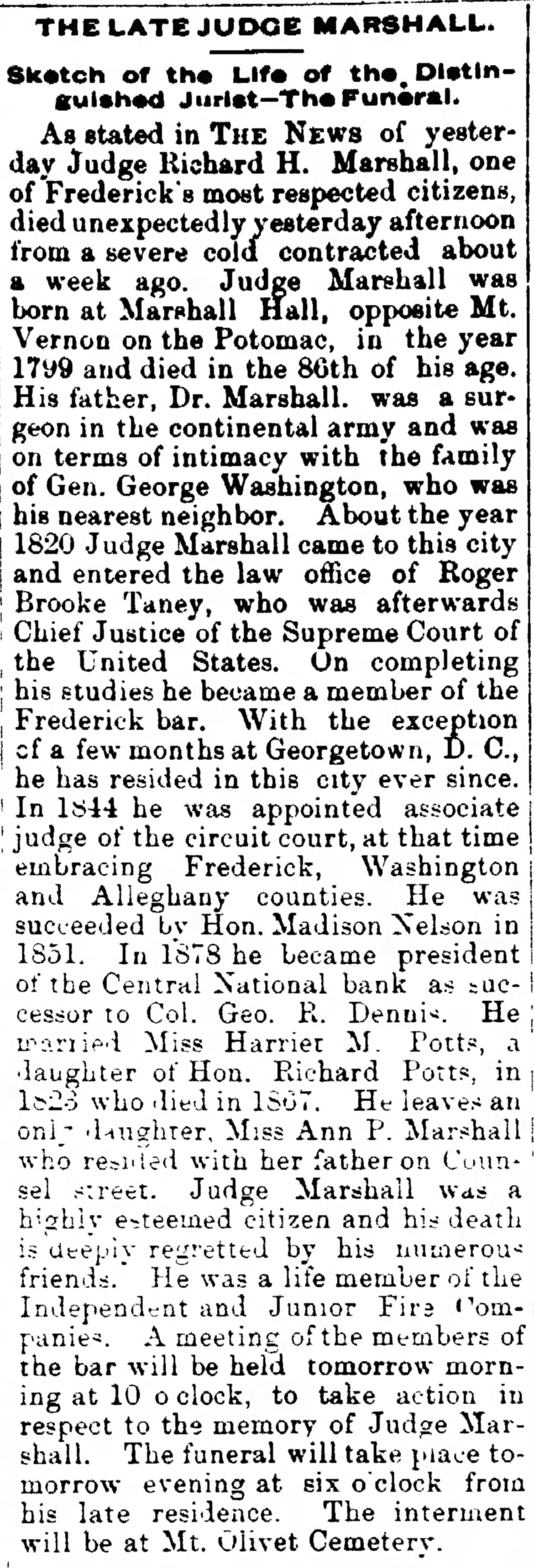

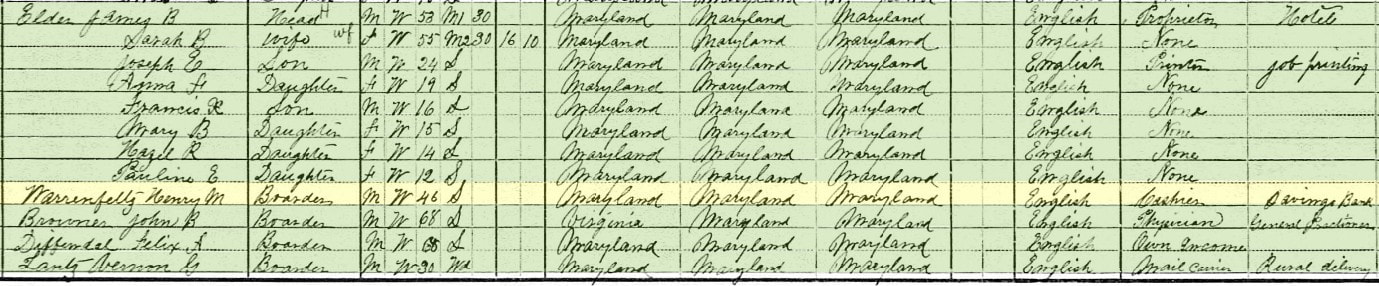

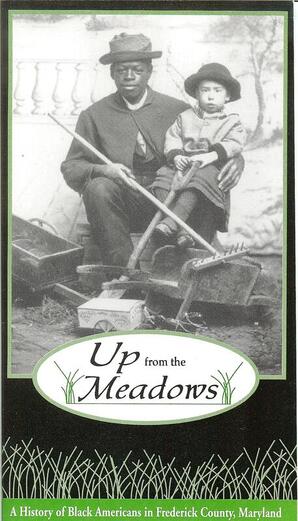

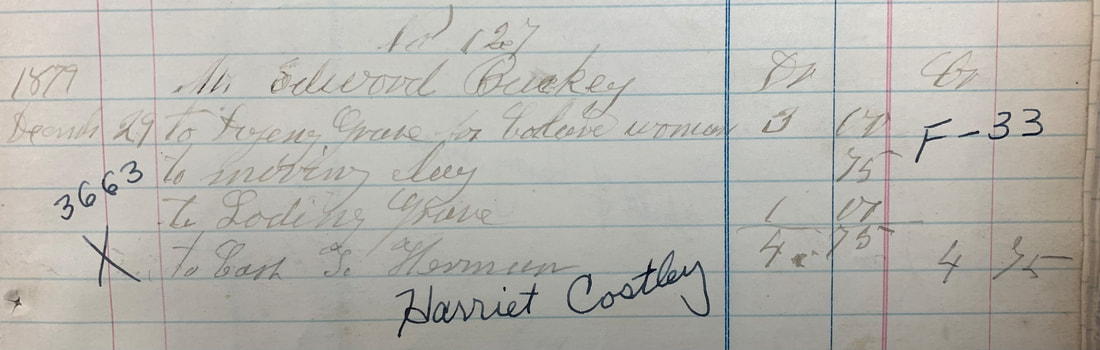

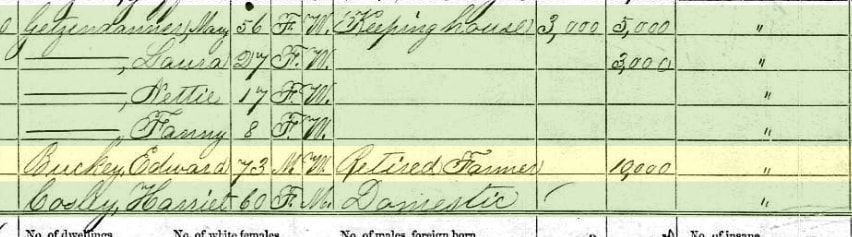

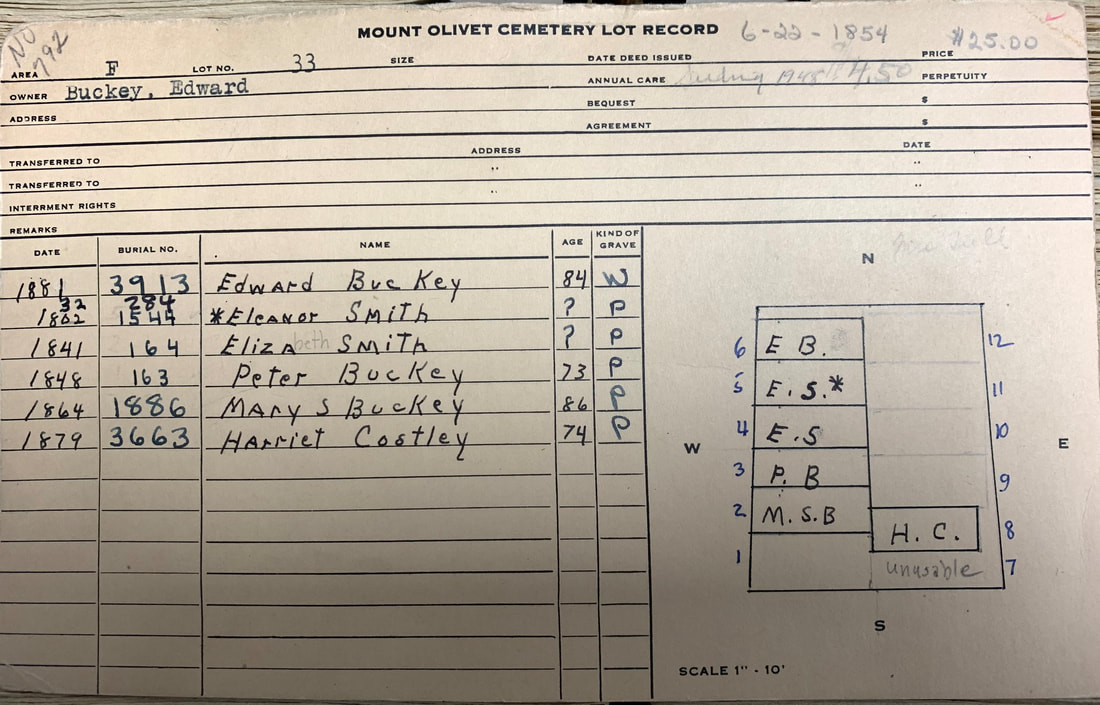

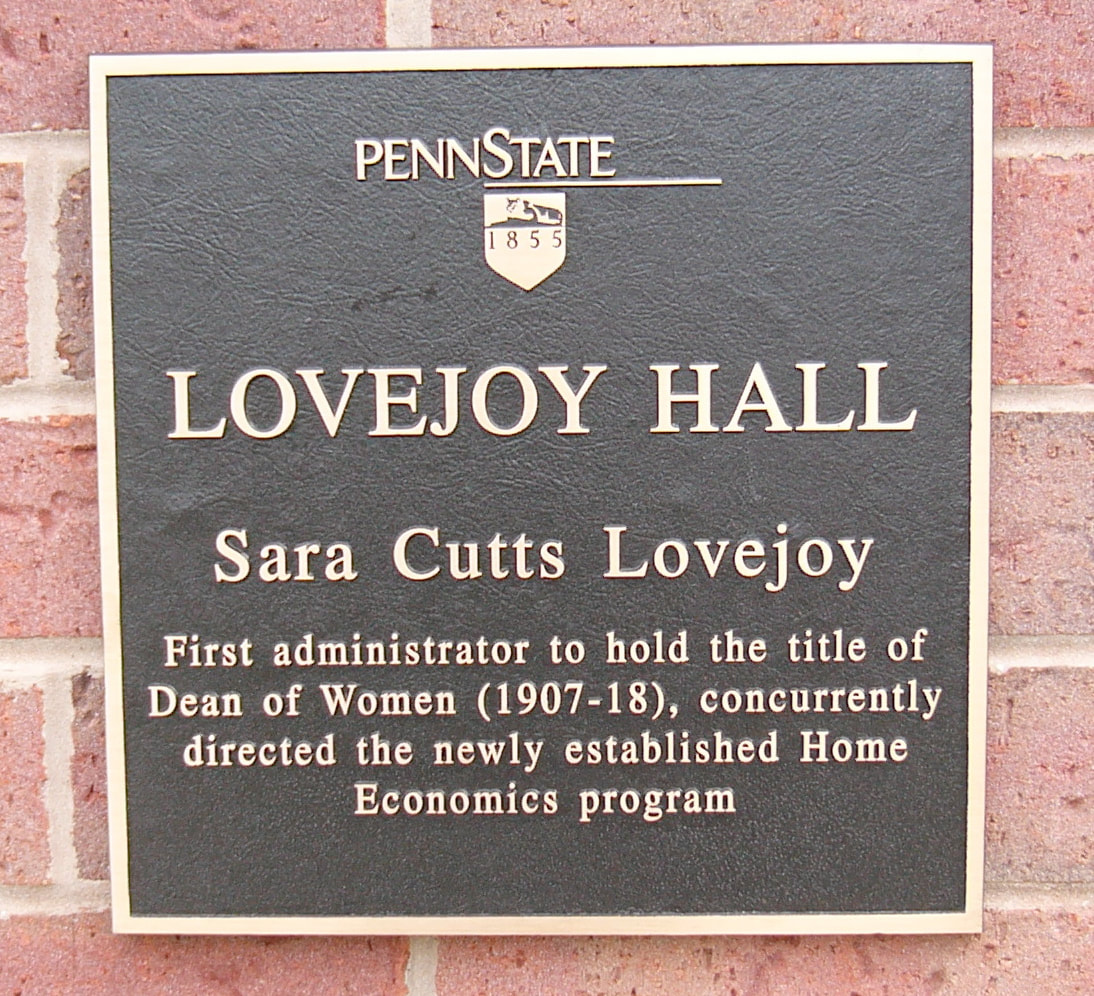

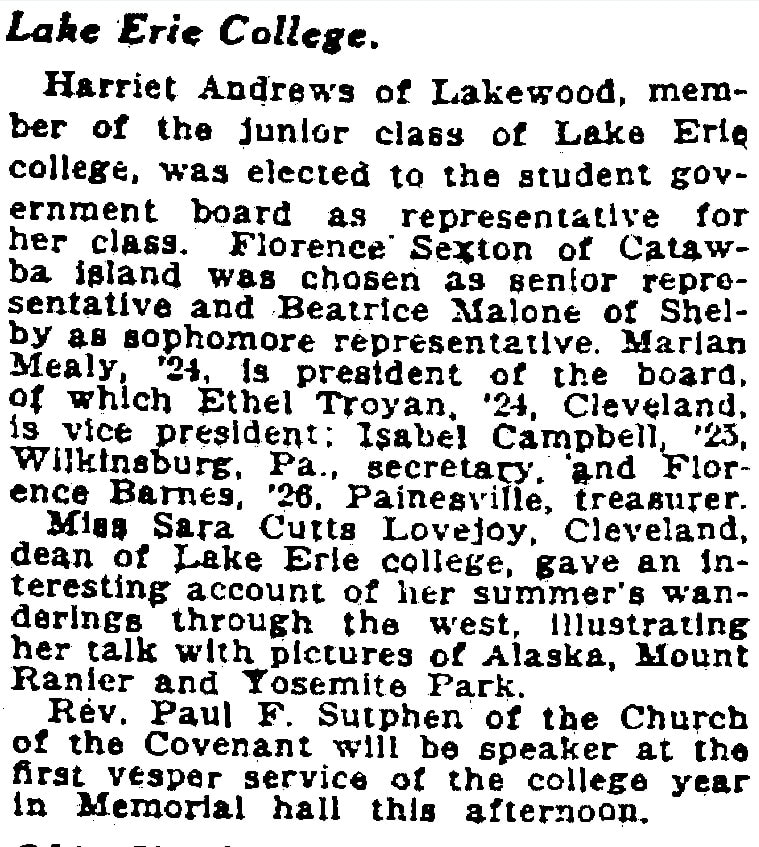

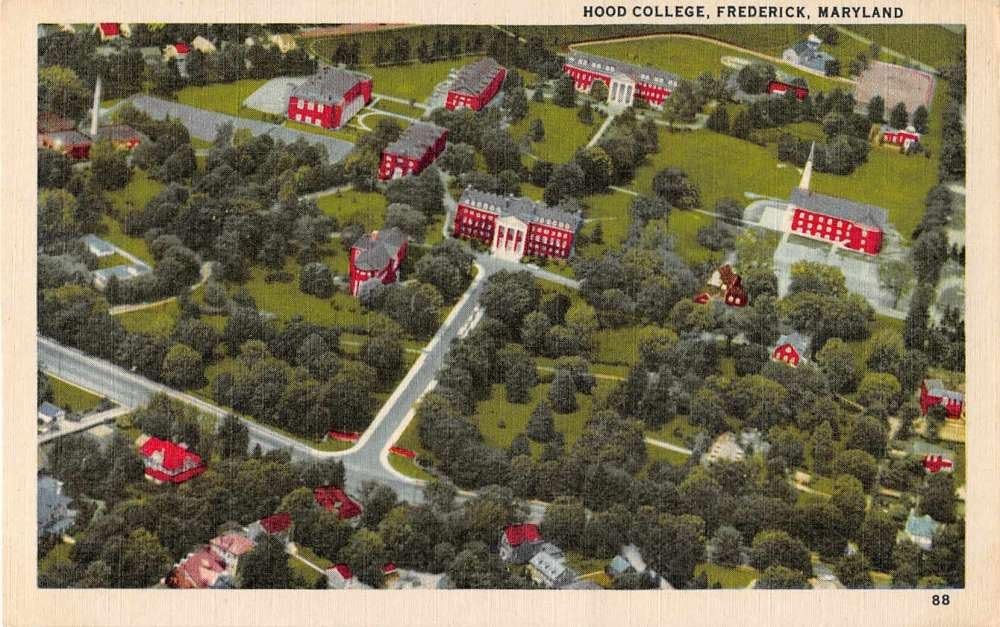

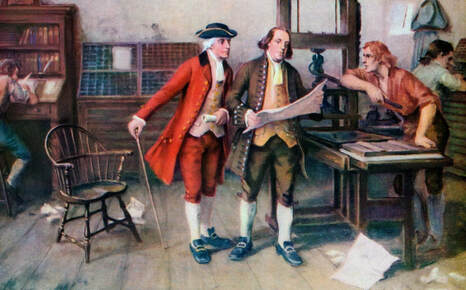

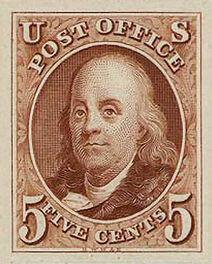

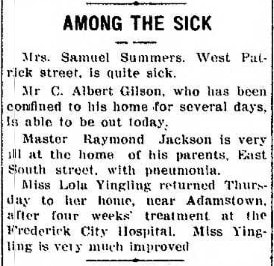

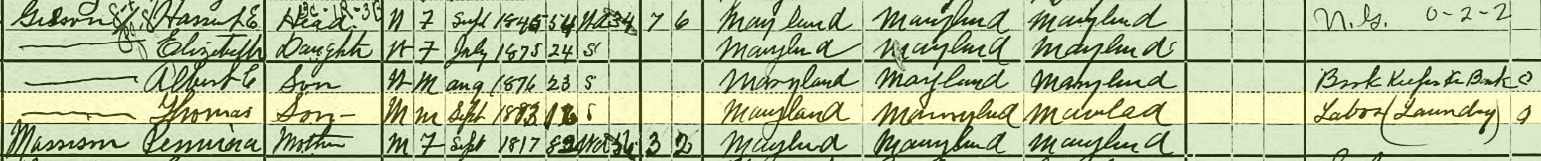

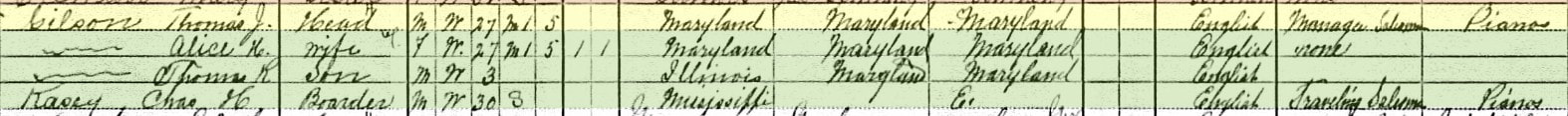

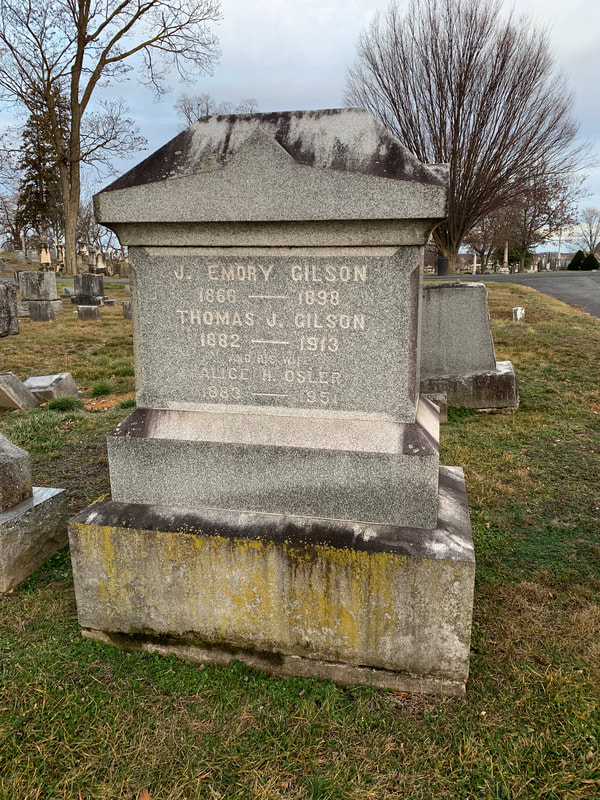

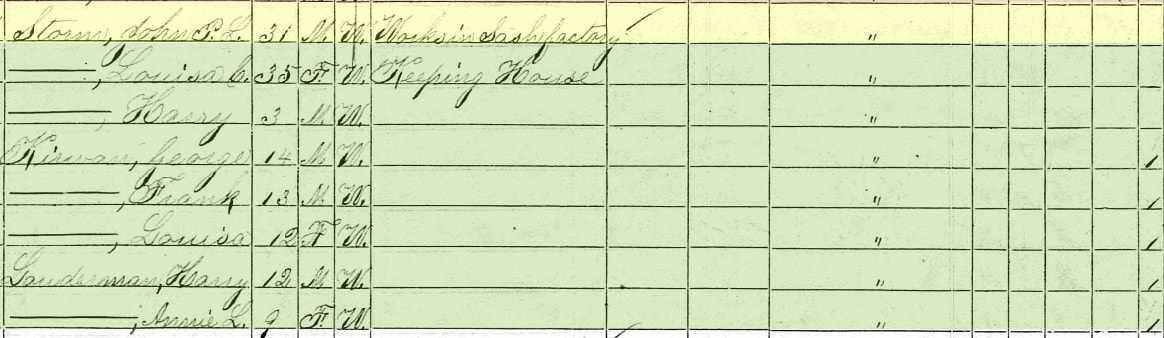

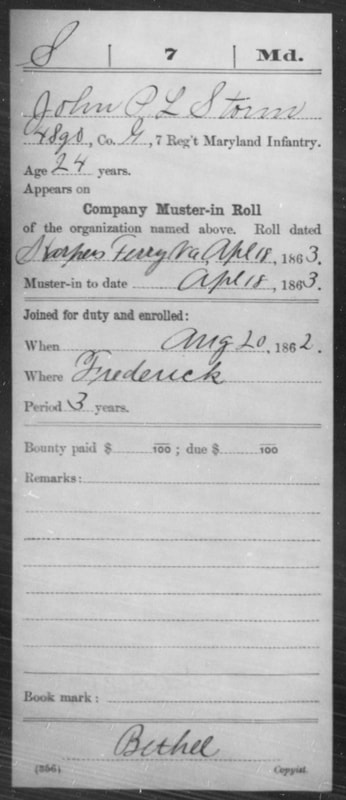

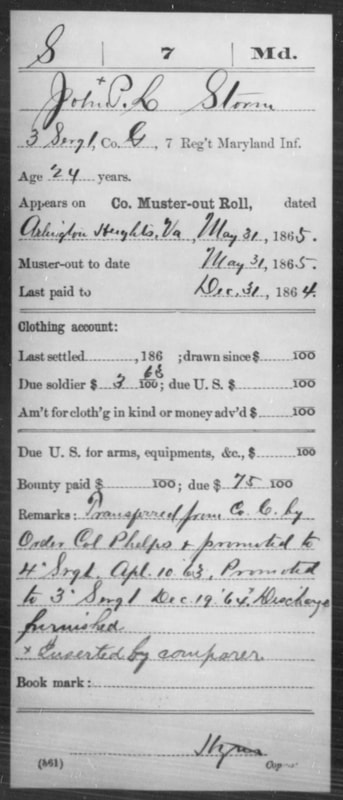

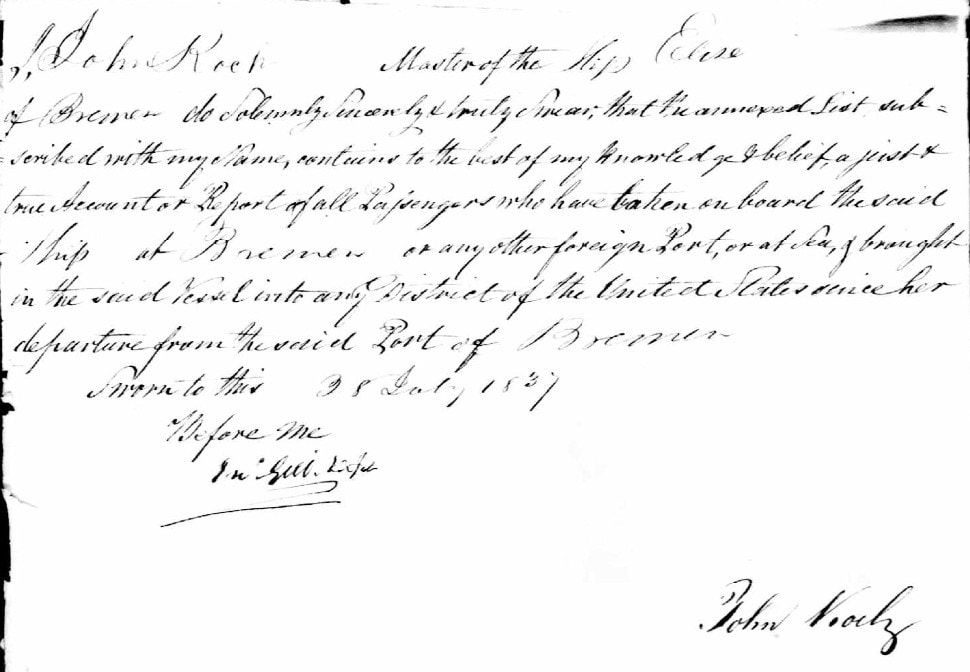

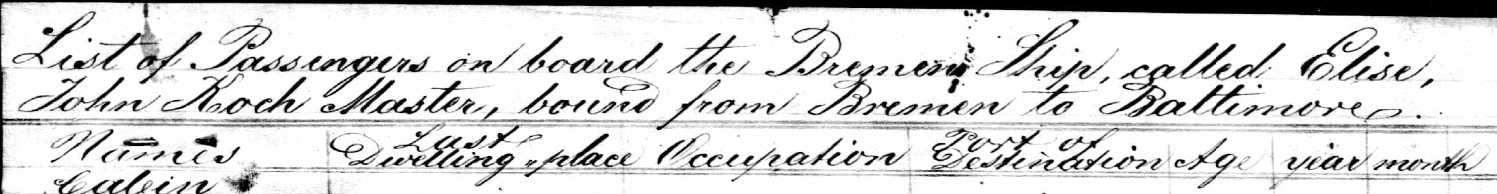

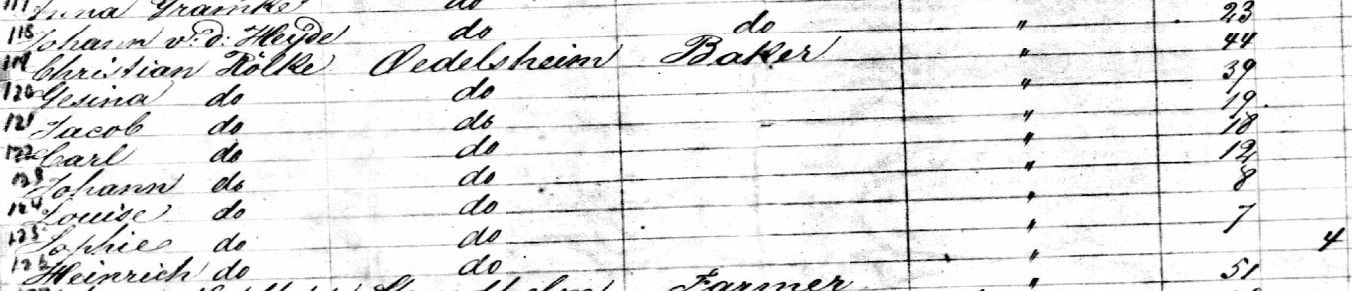

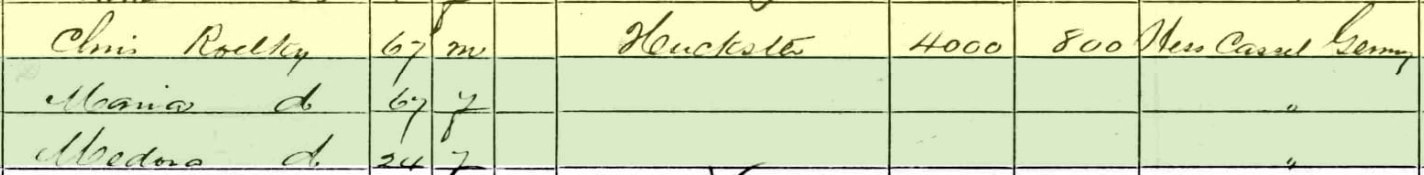

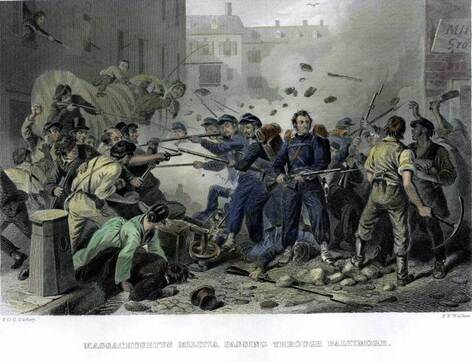

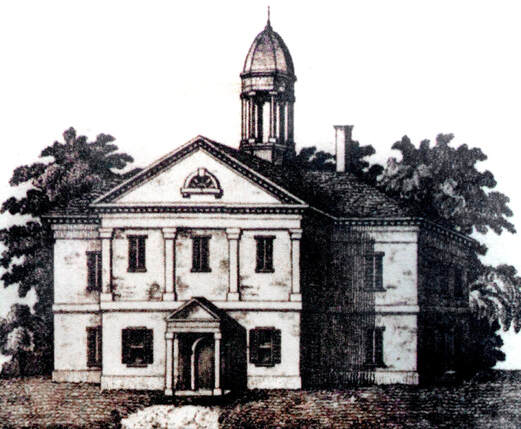

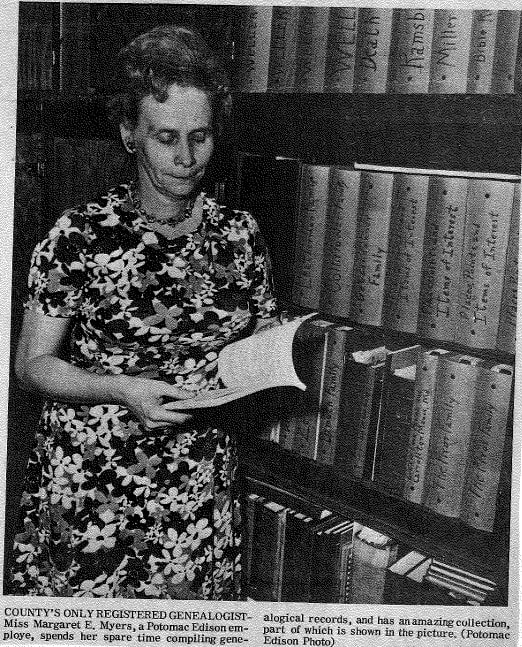

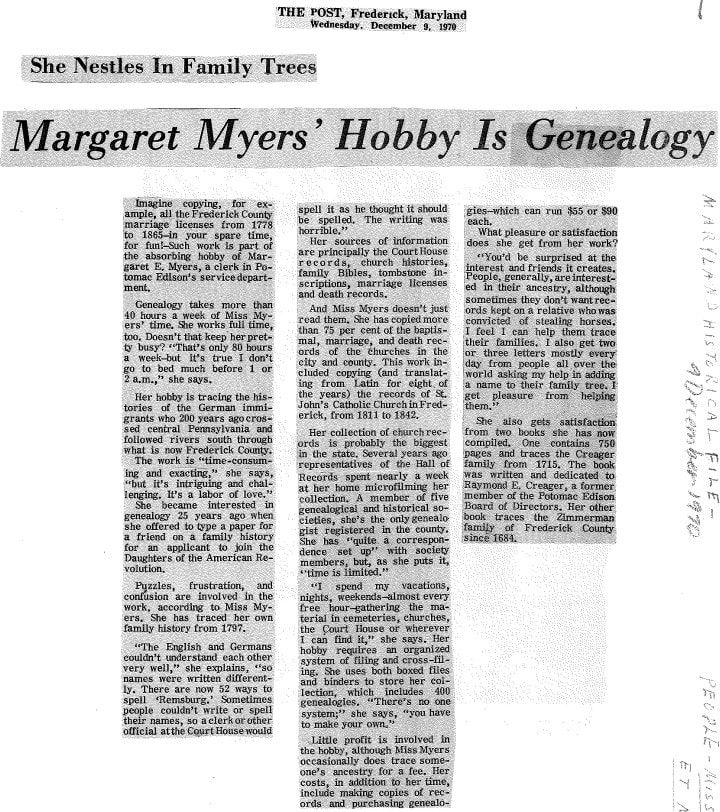

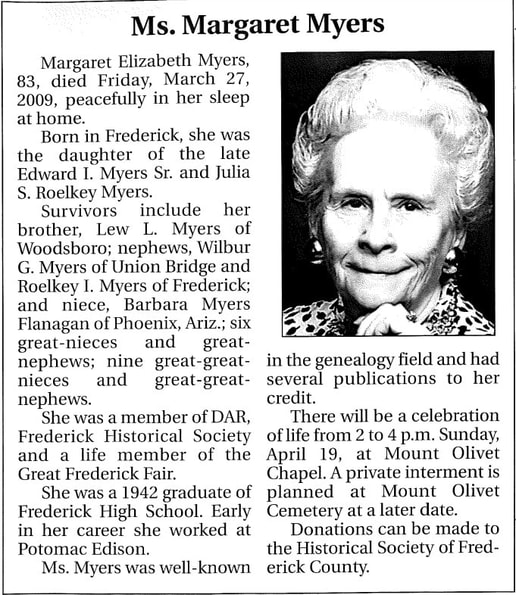

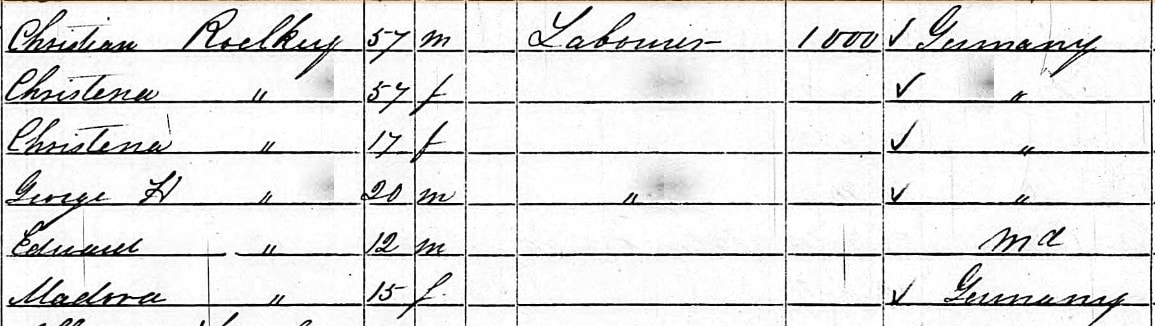

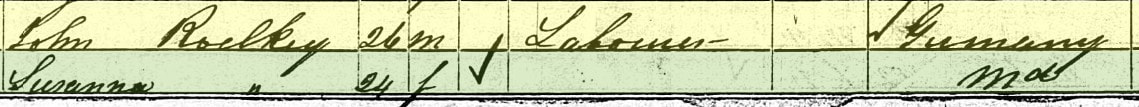

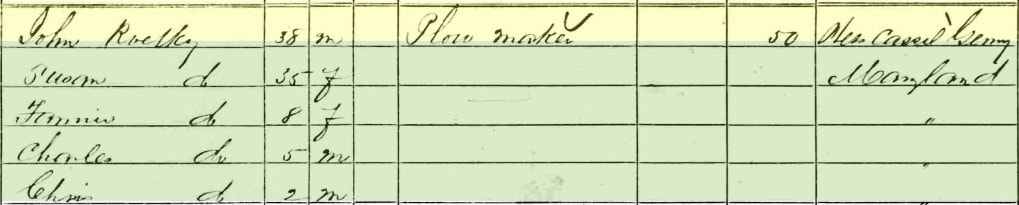

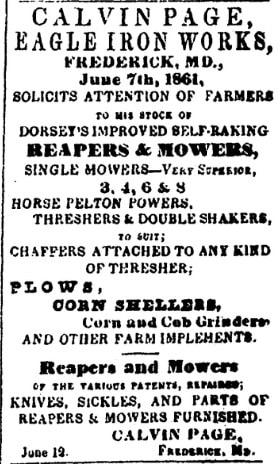

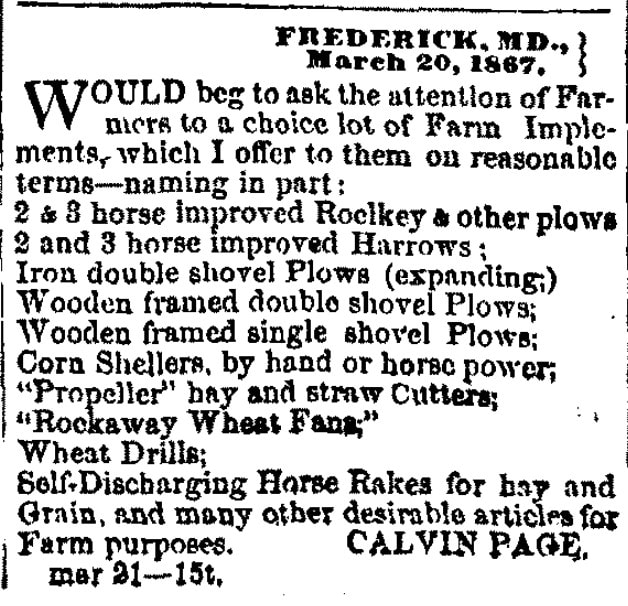

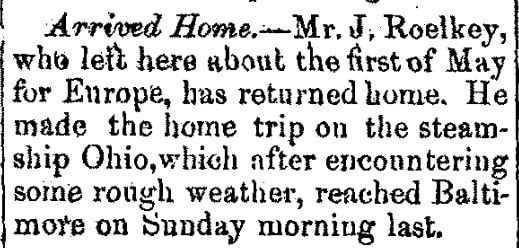

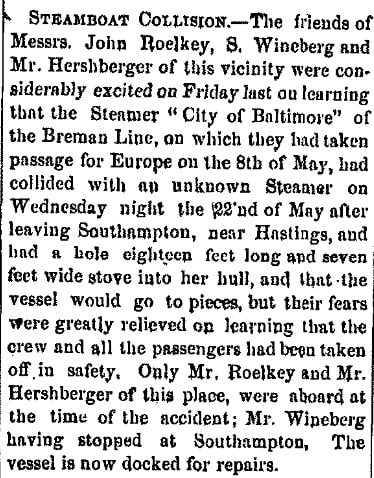

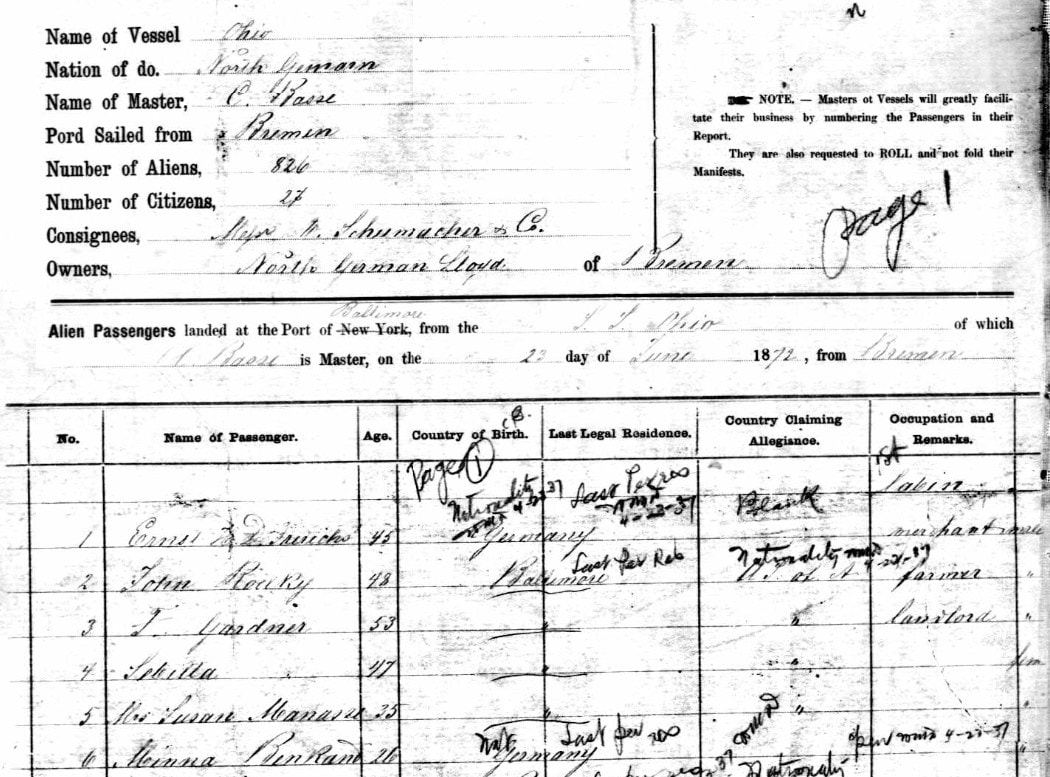

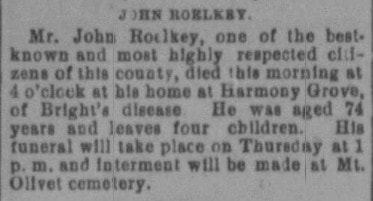

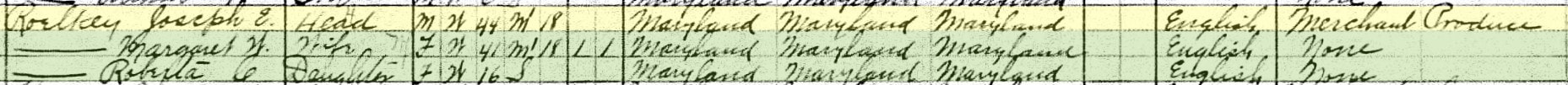

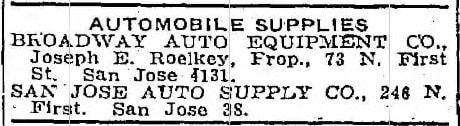

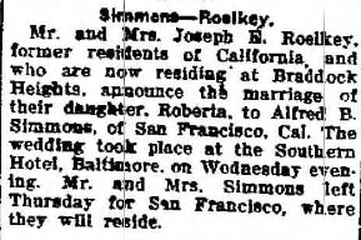

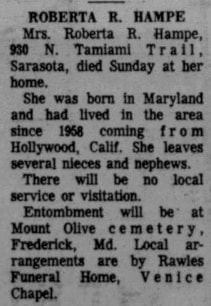

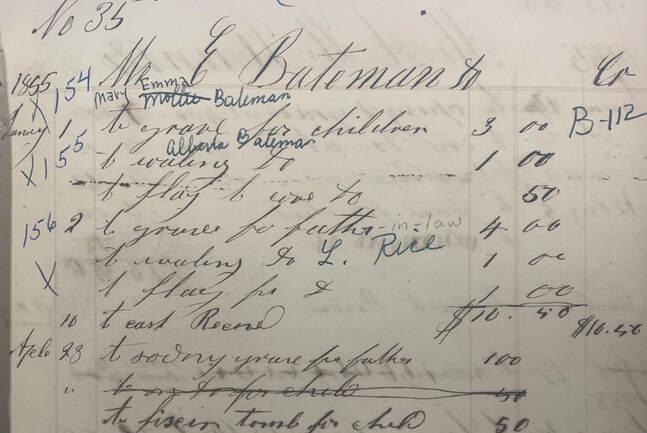

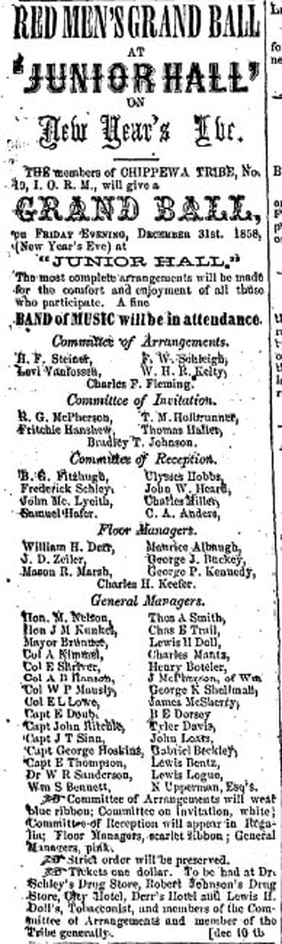

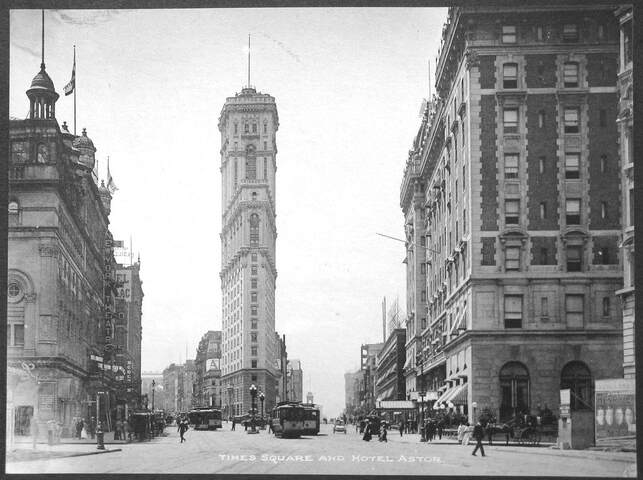

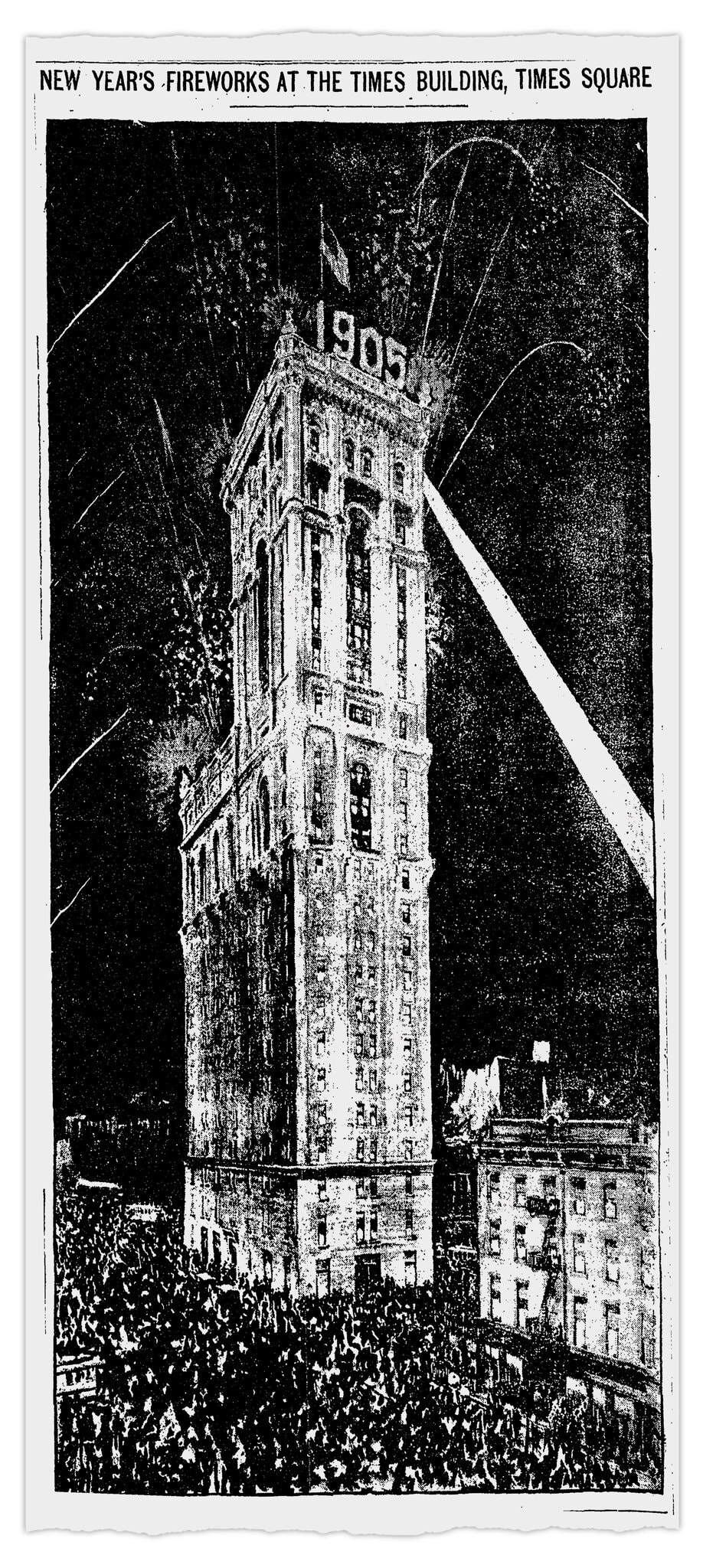

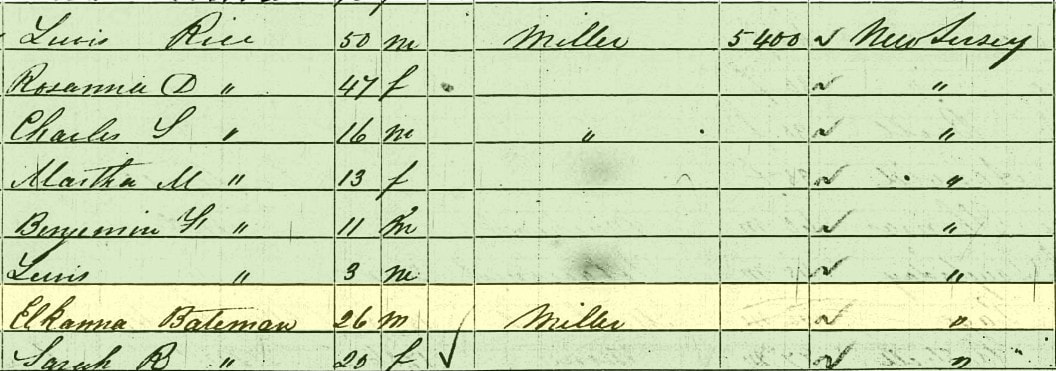

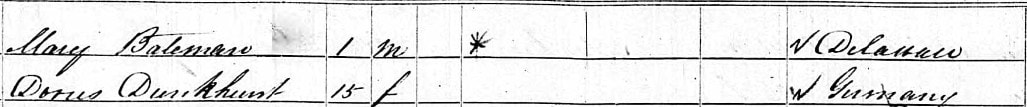

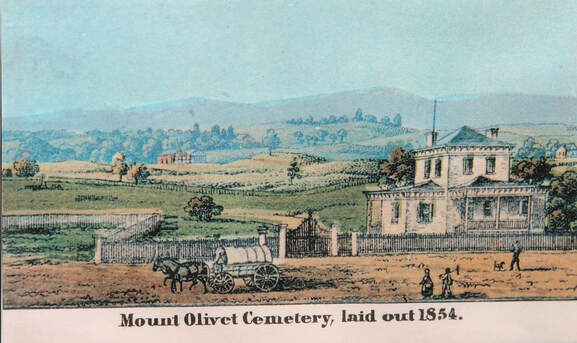

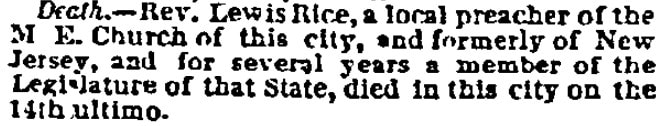

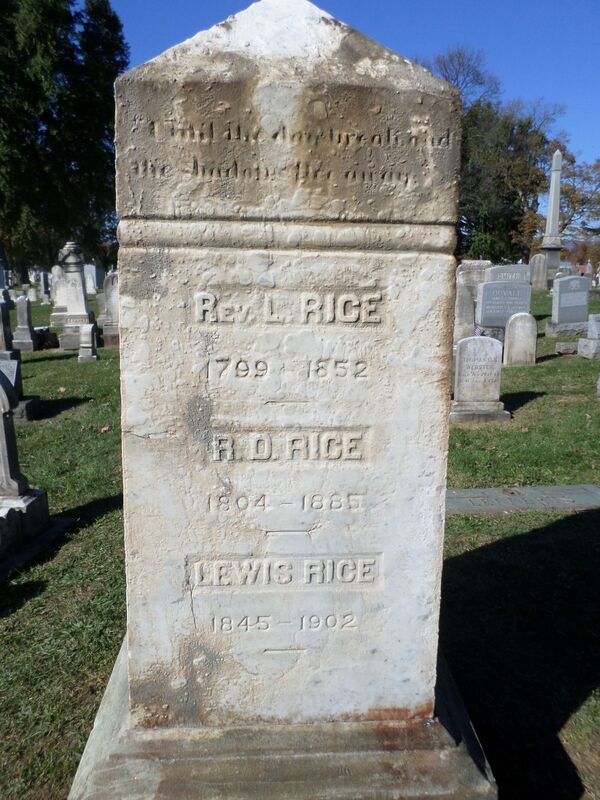

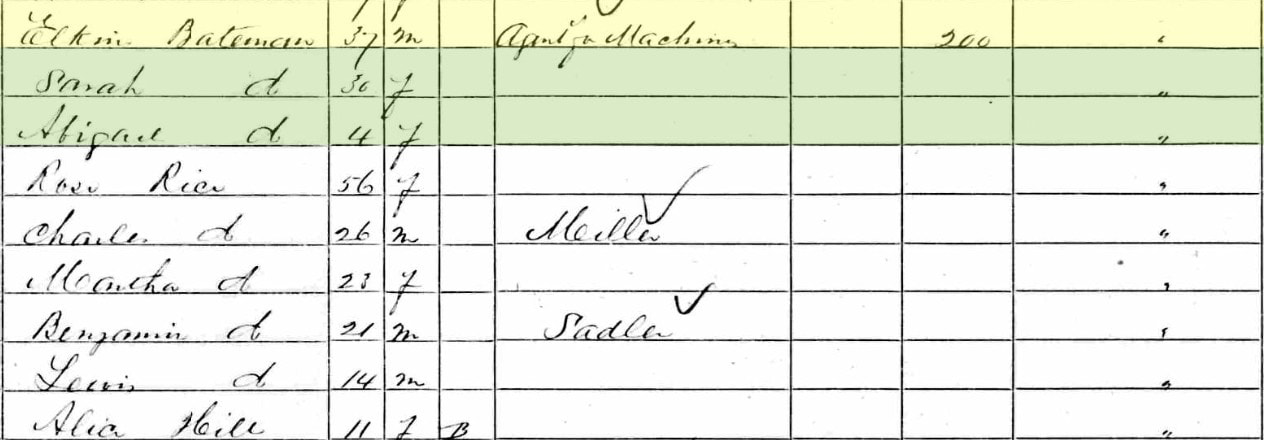

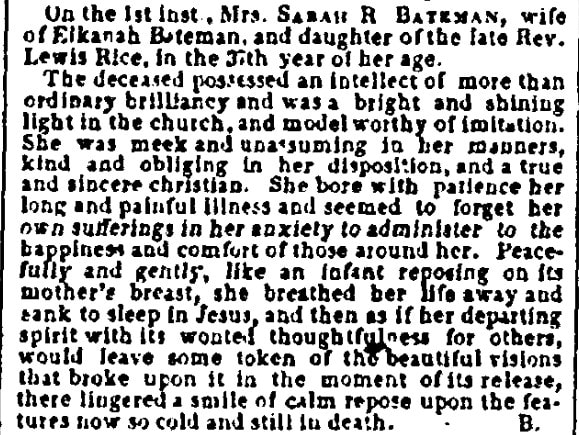

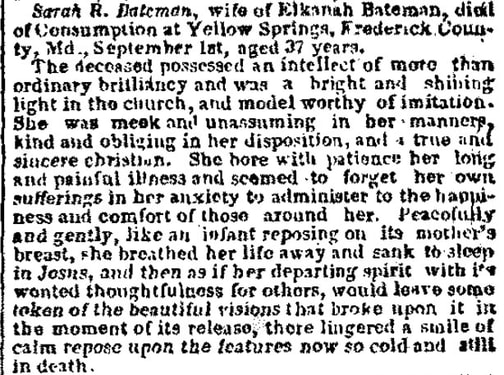

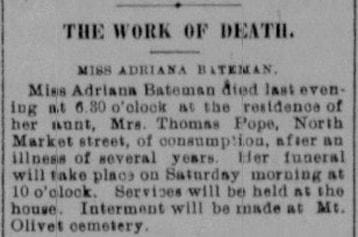

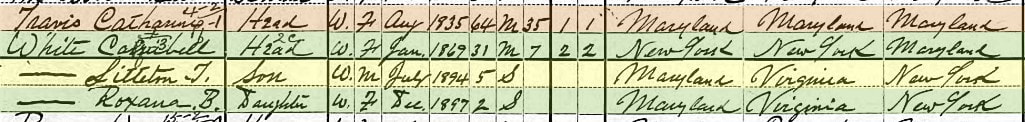

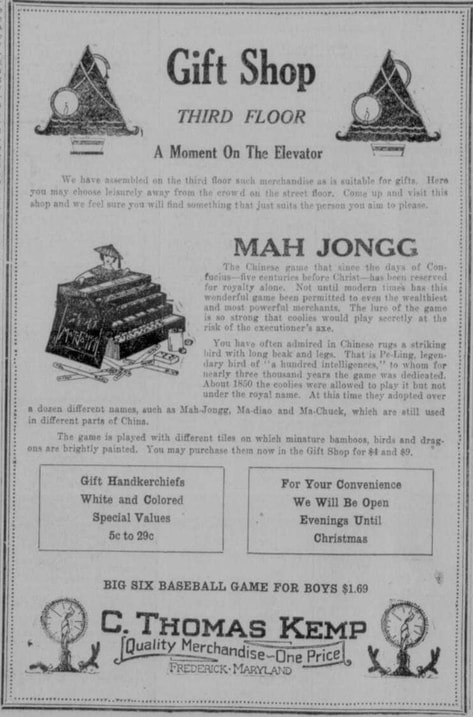

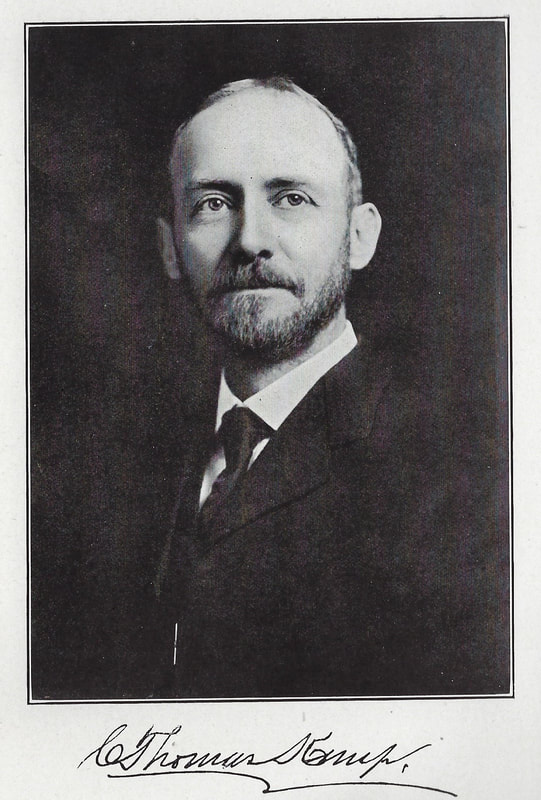

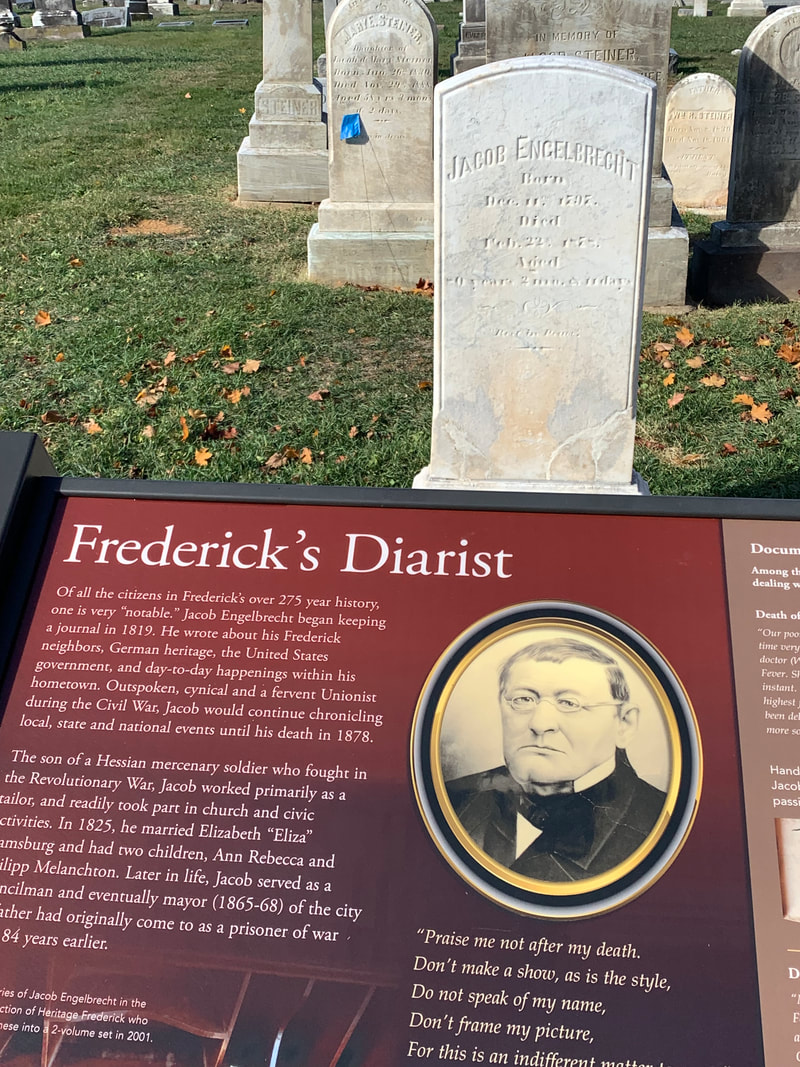

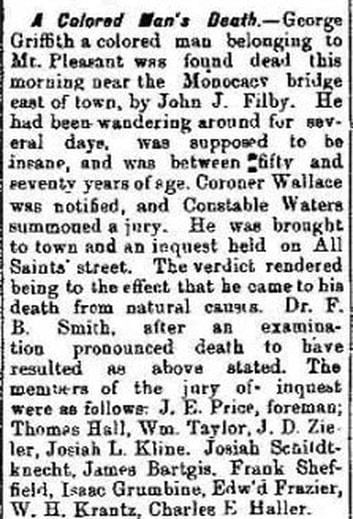

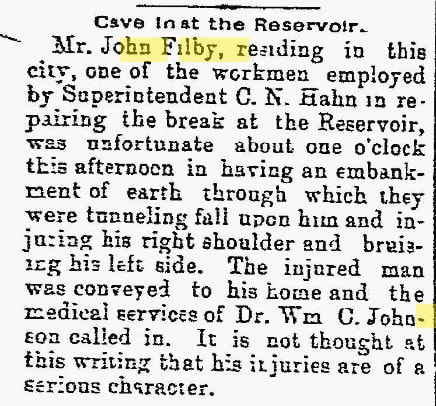

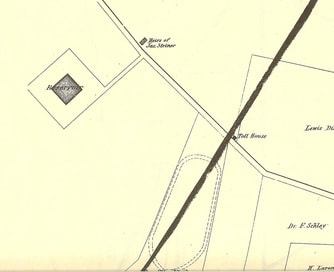

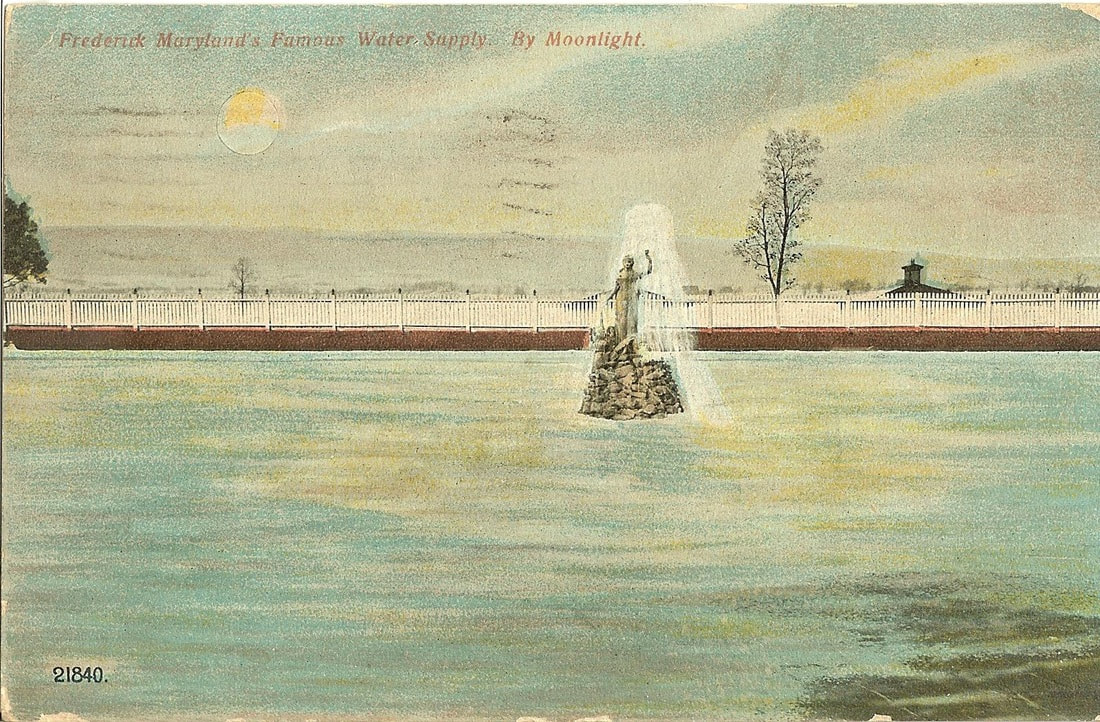

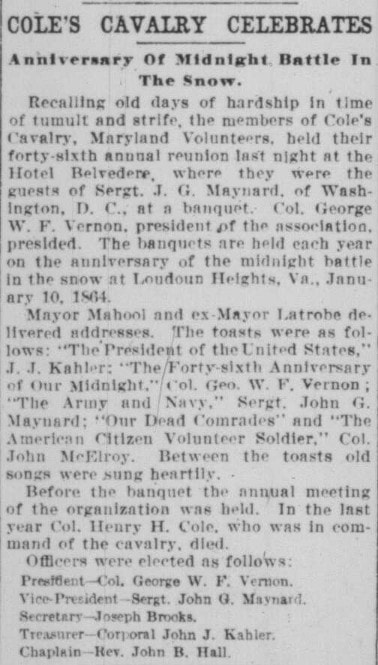

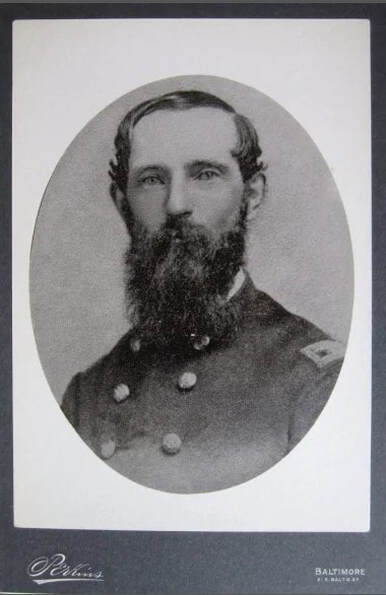

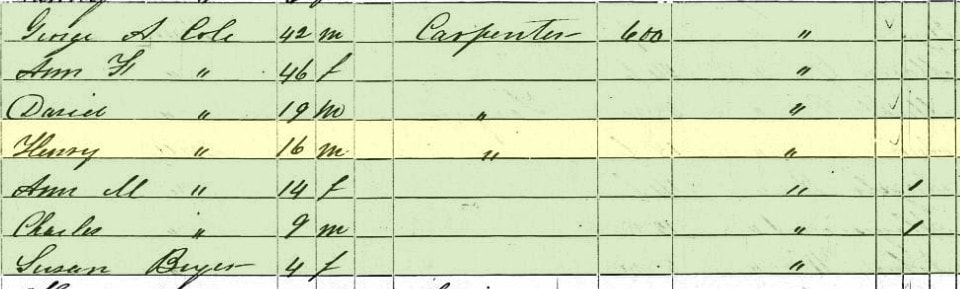

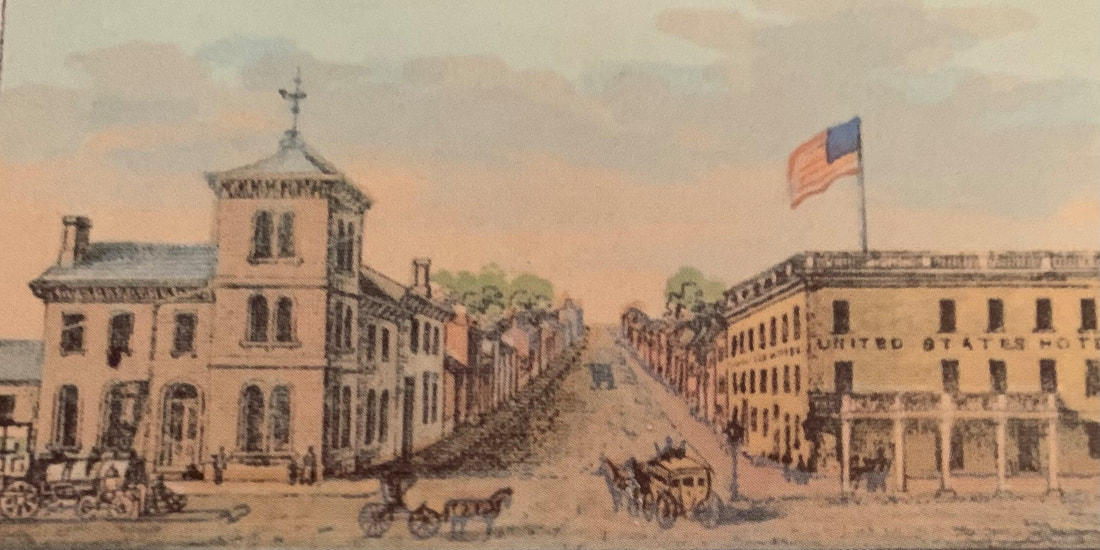

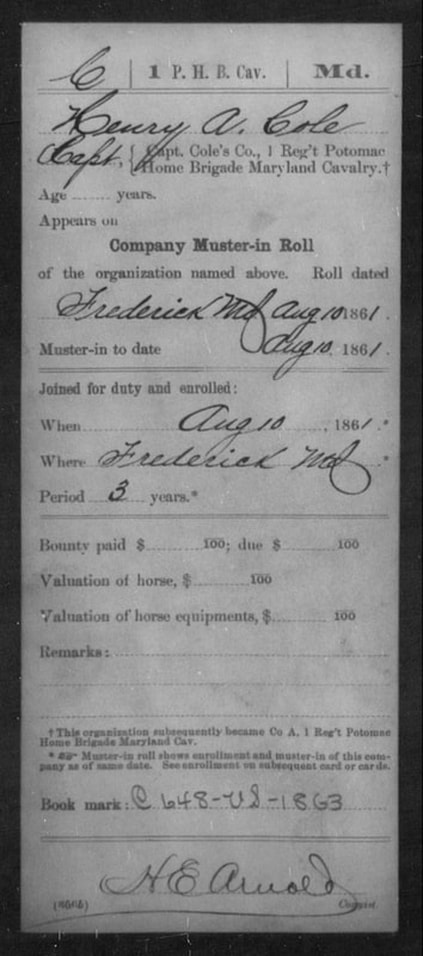

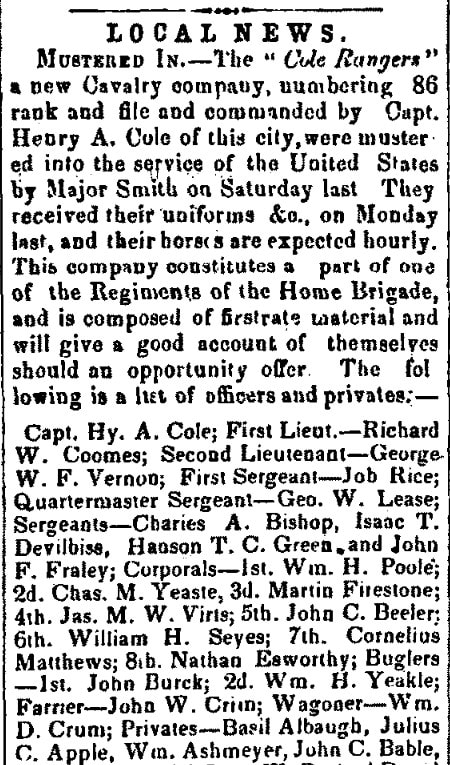

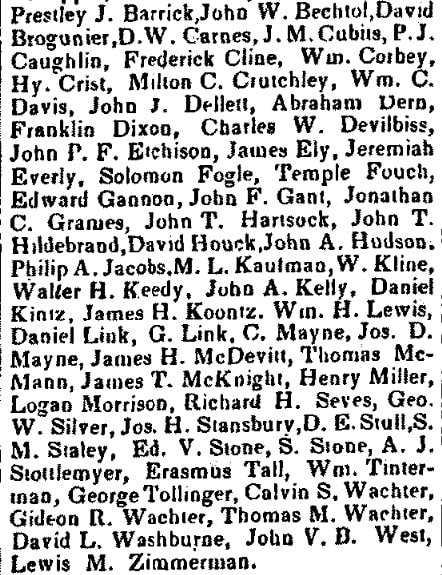

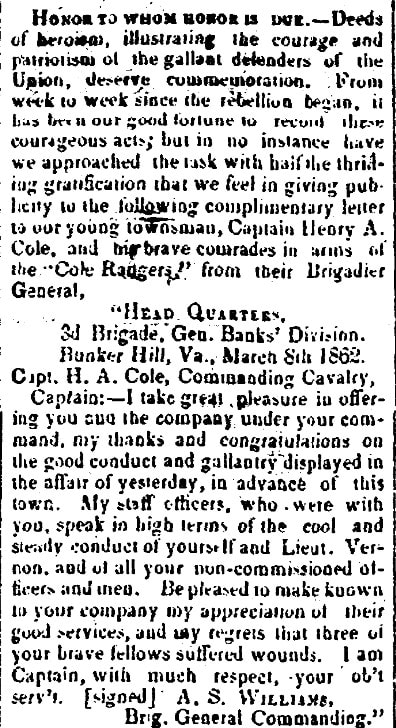

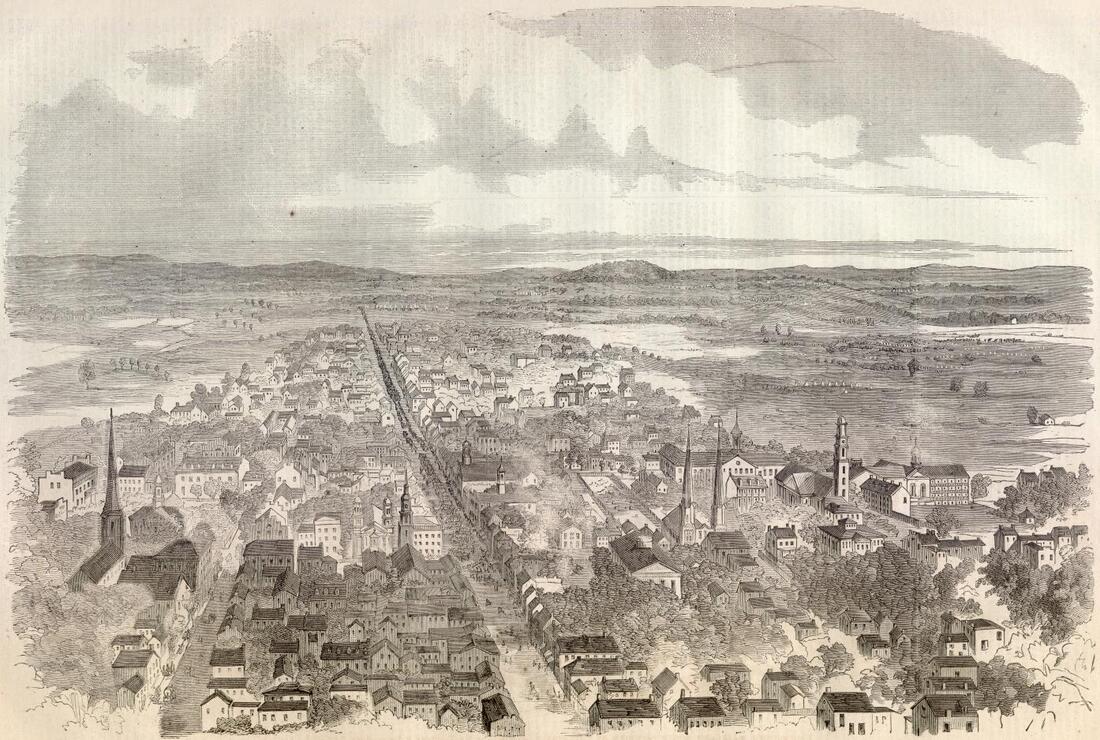

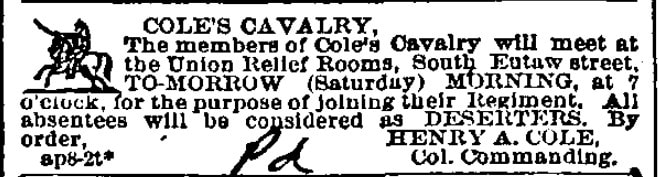

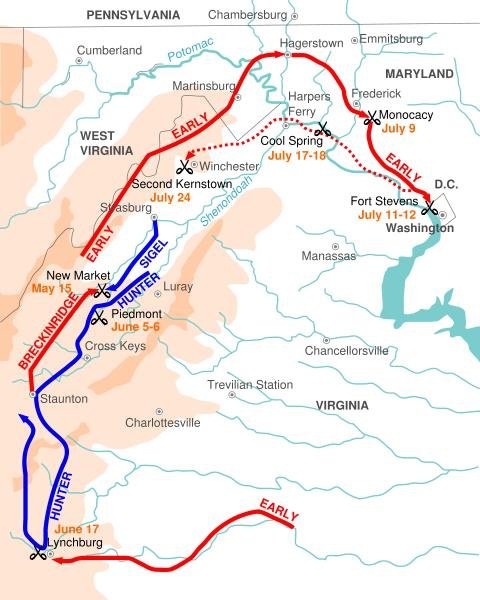

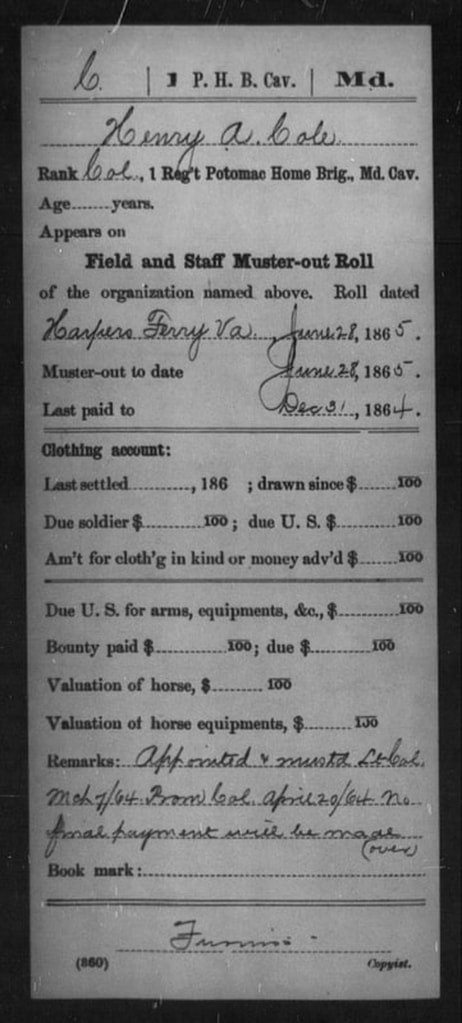

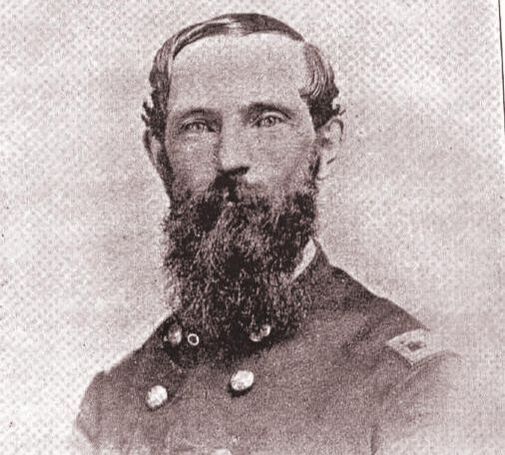

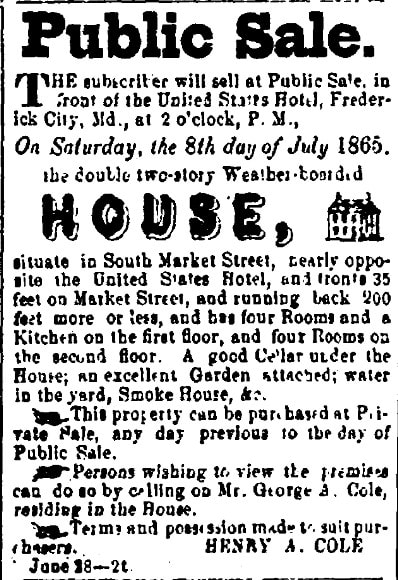

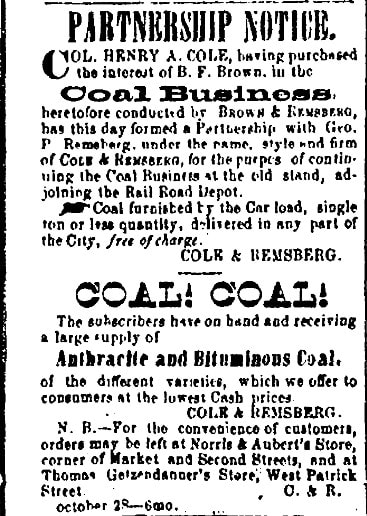

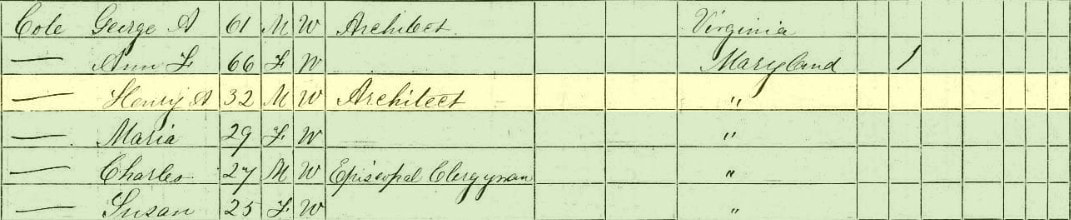

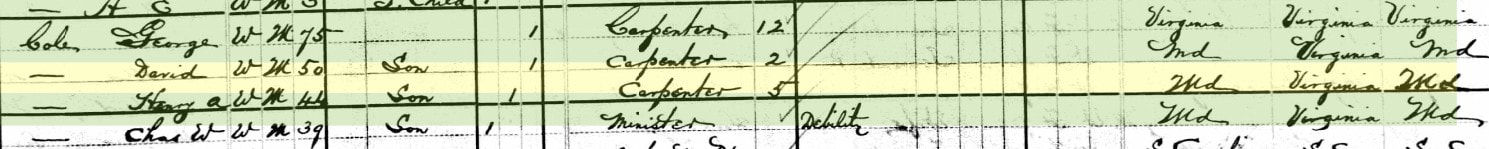

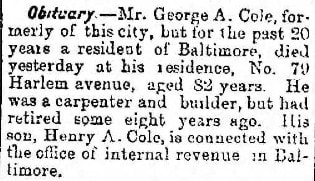

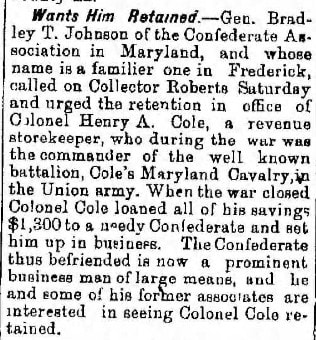

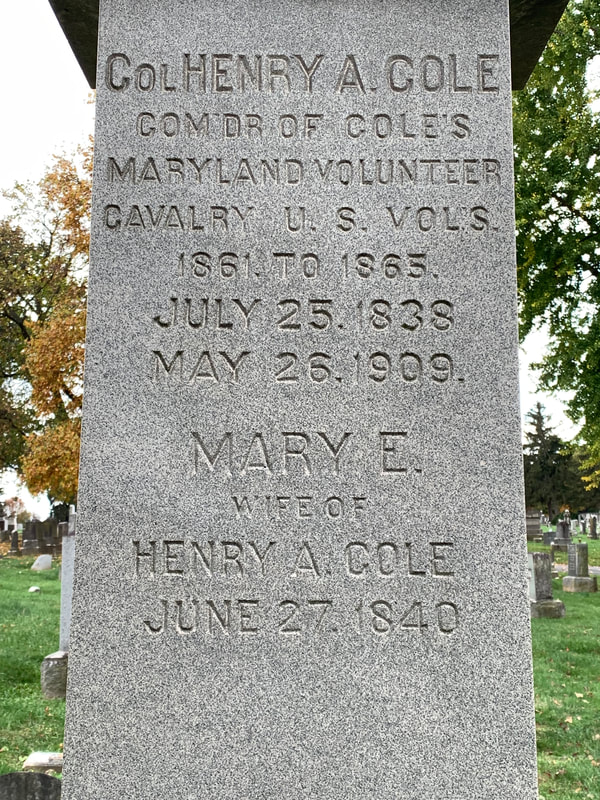

I’m still riding a high from recently checking off an item on my proverbial “bucket list.” This occurred thanks to a trip to a unique destination I’ve wanted to visit for quite some time. For those unfamiliar with the concept, a bucket list is “a list of the experiences or achievements that a person hopes to have, or accomplish, during their lifetime. A bucket list is an itemized list of goals people want to accomplish before they “kick the bucket” — or die.” The true irony lies in the fact that the place I traveled to recently is a location seldom relished by those among the living, yet a stark reality for those who are not. I’m talking about a trip to a cemetery. However, this isn’t any ordinary cemetery, rather it’s thee cemetery—Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts. My recent adventure was more than just a personal quest, it was a professional sojourn—one that will further help guide me, my co-workers and our Friends of Mount Olivet membership group in our quest to further enhance Frederick’s Mount Olivet, originally modeled after the Rural/Garden Cemetery movement of the early 19th century. Dedicated in 1831, Mount Auburn Cemetery is the first rural, or garden, cemetery in the United States. It is the burial site of over 93,000 individuals including many prominent New England families. Here one will discover noted politicians, inventors, social reformers, war heroes, and plenty of authors and artists of note. Mount Auburn Cemetery is also designated as a National Historic Landmark. The grounds are set with classical monuments in a rolling landscaped terrain. This marked a distinct break with Colonial-era burying grounds with rows of upright slate tombstones, many decorated with “death heads” featuring a central winged skull, sometimes with crossed bones nearby, or an hourglass, or any other mortality symbol. I saw several of these stones on the same trip to Massachusetts in various old graveyards located along Boston’s Independence Trail. One of the featured points of interest on the Trail is the Granary Burying Ground across from Boston Common on Tremont Street. Here, you will find immortal patriots like Paul Revere, John Hancock and Sam Adams. Ben Franklin's parents and Mother Goose are also here. The Granary is the most visited burying ground in the northeast with over one million visitors each year. Just up the street from here is Boston’s oldest graveyard with Kings Chapel Burying Ground. The third such graveyard for the “Tombstone Tourist” on the Independence Trail is Copp’s Hill Burying Ground on the North End of the city. Established in 1659, this is the city’s largest graveyard and it is within easy view of the fabled North Church’s steeple where Paul Revere had placed lanterns on that fateful night in April, 1775 signaling “one if by land, and two if by sea.” As said earlier, these three examples represent the accepted style for burying grounds here in North America until Mount Auburn Cemetery was planned, and dare I say executed, in the late 1820s leading to a dedication in 1831. The new burial ground project was designed largely by Henry Alexander Scammell Dearborn with assistance from Jacob Bigelow and Alexander Wadsworth. Bigelow, a medical doctor, came up with the idea for Mount Auburn as early as 1825, though a site was not acquired until five years later. Dr. Bigelow was concerned about the unhealthiness of burials under churches as well as the possibility of running out of space in Boston. Epidemics causing widespread death gave pause to rethink burial being conducted in the rural outskirts instead of in the heart of residential centers of our early large cities. With help from the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, Mount Auburn Cemetery was founded on 70 acres of land authorized by the Massachusetts Legislature for use as a garden, or rural, cemetery. The original land cost $6,000 and would later be extended to 170 acres. The first president of the Mount Auburn Association was a Supreme Court Justice named Joseph Story. I found his grave, and it soon made me reflect that if I were an employee of Mount Auburn (instead of Mount Olivet) and writing this particular blog series, I would certainly have a clever title for his fitting “Story in Stone.” I also learned that Justice Story's dedication address, delivered on September 24th, 1831, established the model for many more addresses in the following three decades with particular emphasis on President Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address which took place right up the road from Frederick. The national cemetery Lincoln would dedicate there in 1863 adjoins Evergreen Cemetery, a burying ground designed by the very same landscape architect who designed Mount Olivet. This was James Belden. The appearance of rural, or garden, cemetery landscapes coincided with the rising popularity of the term "cemetery," crudely translated from Greek to mean "a sleeping place.” This language, and outlook, eclipsed the previous harsh view of death and the afterlife embodied by old burying grounds and churchyards such as those previously mentioned in Boston. The land that became Mount Auburn Cemetery was originally named Stone's Farm, though locals referred to it as "Sweet Auburn" after the 1770 poem "The Deserted Village" by Oliver Goldsmith. Mount Auburn was inspired by Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris and is credited as the beginning of the American public parks and gardens movement. It was an inspiration to cemetery designers across the country, setting the style for other suburban cemeteries such as Laurel Hill Cemetery (Philadelphia, 1836), Mount Hope Cemetery (Bangor, Maine, 1834), Green-Wood Cemetery (Brooklyn, 1838), Green Mount Cemetery (Baltimore, Maryland, 1839) Mount Hope Cemetery (Rochester, NY, 1838), Lowell Cemetery (Lowell, Massachusetts, 1841), Allegheny Cemetery (Pittsburgh, 1844), Albany Rural Cemetery (Menands, New York, 1844), Swan Point Cemetery (Providence, Rhode Island 1846), Spring Grove Cemetery (Cincinnati, 1844), and Forest Hills Cemetery (Jamaica Plain, 1848) as well as Oakwood Cemetery in Syracuse, New York. It can be considered the link between Capability Brown's English landscape gardens and Frederick Law Olmsted's Central Park in New York (1850s). The 174-acre cemetery is important both for its historical aspects and for its role as an arboretum. It is Watertown's largest contiguous open space and extends into Cambridge to the east, adjacent to the Cambridge City Cemetery and Sand Banks Cemetery. It was designated a National Historic Landmark District in 2003 for its pioneering role in 19th-century cemetery development. Upon arrival, I was immediately impressed with the main entrance off Mount Auburn Street, and was given assistance by a guide positioned just inside the gate. The Story Chapel was a great place to start exploration with cemetery map/guide in hand. In the near distance, a beautiful pond could be found at the base of a hill topped with another, yet more majestic looking chapel known as Bigelow Chapel. I know this may seem crass, but looking at the well-manicured grass, bountiful plantings and these two chapel features at the entrance conjured up images of the entrance to DisneyWorld. I wonder if this place was an inspiration to Disney ground designers in any way? Regardless, with this being a cemetery, visitors can find themselves in a perpetual state of “Yesterland.” My exploration of Mount Auburn took place on a sunny and temperate Tuesday morning. The cemetery was not very crowded, and the vast canopy of trees provided plenty of shade. This shade also creates the magic of the landscape with light and darkness accenting the monuments and surrounding trees and vegetation. I had performed my advance work in reviewing notable residents of this place. There were plenty, such as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Julia Ward Howe, Winslow Homer, Henry Cabot Lodge, Arthur Schlessinger, Jr., and Charles Sumner. Of particular interest to me were three "more modern" residents: Hall of Fame sportscaster Curt Gowdy, architect-engineer R. Buckminster Fuller, developer of the geodesic dome, and psychologist-behavioralist B. F. Skinner, a Harvard professor who gave test rats and pigeons fits with his operant conditioning chamber (aka “Skinner Box”). Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include the poems "Paul Revere's Ride", "The Song of Hiawatha", and "Evangeline." He was the first American to completely translate Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy and was one of the "fireside poets" from New England. Winslow Homer (February 24th, 1836 – September 29th, 1910) was an American landscape painter and illustrator, best known for his marine subjects. He is considered one of the foremost painters of 19th-century America and a preeminent figure in American art in general. Largely self-taught, Homer began his career working as a commercial illustrator. He subsequently took up oil painting and produced major studio works characterized by the weight and density he exploited from the medium. He also worked extensively in watercolor, creating a fluid and prolific oeuvre, primarily chronicling his working vacations. Arthur Meier Schlesinger Jr. (October 15th, 1917 – February 28th, 2007) was an American historian, social critic, and public intellectual. The son of the influential historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr. and a specialist in American history, much of Schlesinger's work explored the history of 20th-century American liberalism. In particular, his work focused on leaders such as Harry S. Truman, Franklin D. Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, and Robert F. Kennedy. In the 1952 and 1956 presidential campaigns, he was a primary speechwriter and adviser to the Democratic presidential nominee, Adlai Stevenson II. Schlesinger served as special assistant and "court historian" to President Kennedy from 1961 to 1963. He wrote a detailed account of the Kennedy administration, from the 1960 presidential campaign to the president's state funeral, titled A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House, which won the 1966 Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography. Julia Ward Howe ( May 27, 1819 – October 17, 1910) was an American author and poet, known for writing the "Battle Hymn of the Republic" as new lyrics to an existing song, and the original 1870 pacifist Mothers' Day Proclamation. She was also an advocate for abolitionism and a social activist, particularly for women's suffrage. Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811 – March 11, 1874) was a U.S. Senator from Massachusetts, serving from 1851 until his death in office in 1874. A staunch and vocal proponent of the Abolitionist movement, he gave a speech dubbed the "Crime Against Kansas" condemning slavery on May 22nd, 1856, which prompted South Carolina Congressman Preston Brooks to assault and severely injure him while on the Senate floor. He was absent from the Senate on account of the injuries caused by Brooks from 1856 to December 1859. Curtis Edward Gowdy (1919 –2006) was an American sportscaster. He called Boston Red Sox games on radio and TV for 15 years, and then covered many nationally televised sporting events, primarily for NBC Sports and ABC Sports in the 1960s and 1970s. He coined the nickname "The Granddaddy of Them All" for the Rose Bowl Game, taking the moniker from the Cheyenne Frontier Days in his native Wyoming. Richard Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983) was an American architect, systems theorist, writer, designer, inventor, philosopher, and futurist. Fuller developed numerous inventions, mainly architectural designs, and popularized the widely known geodesic dome; carbon molecules known as fullerenes were later named by scientists for their structural and mathematical resemblance to geodesic spheres. Burrhus Frederic Skinner (March 20, 1904 – August 18, 1990) was an American psychologist, behaviorist, inventor, and social philosopher. He was the Edgar Pierce Professor of Psychology at Harvard University from 1958 until his retirement in 1974. Considering free will to be an illusion, Skinner saw human action as dependent on consequences of previous actions, a theory he would articulate as the principle of reinforcement: If the consequences to an action are bad, there is a high chance the action will not be repeated; if the consequences are good, the probability of the action being repeated becomes stronger.  Barbara Fritchie (1766-1862) Barbara Fritchie (1766-1862) I wanted to find a few individuals buried here in Mount Auburn with definitive connections to Frederick, Maryland and/or former residents buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery. Of these, most can be linked to the American Civil War, and our heroine Barbara Fritchie. The gray-headed “Grand Dame” gained universal fame due to a Massachusetts author named John Greenleaf Whittier (1807-1892). Many literary historians claim that Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's patriotic tale of Paul Revere (published in 1861) helped inspire fellow "fireside poet" John Greenleaf Whittier to write "The Ballad of Barbara Frietchie" in 1863. Whittier is not buried in Mount Auburn, but was laid to rest in his hometown of Amesbury, Massachusetts in Union Cemetery. I did, however, revel in finding some other decedents in Mount Auburn, who had once walked the same streets of Frederick that we all know and love. Perhaps some of these may have even visited Mount Olivet while they were here? The following are a few individuals that I specifically sought out while at Mount Auburn. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.  Edward Shriver Edward Shriver Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (August 29, 1809 – October 7, 1894) was an American physician, poet, and polymath based in Boston. Grouped among "the fireside poets," he was acclaimed by his peers as one of the best writers of the day. His most famous prose works are the "Breakfast-Table" series, which began with The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table (1858). He was also an important medical reformer. In addition to his work as an author and poet, Holmes also served as a physician, professor, lecturer, inventor, and, although he never practiced it, he received formal training in law. Holmes would come to Frederick in September, 1862 after learning that his son, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. had been wounded at the Battle of Antietam on September 17th while fighting with the 20th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment of the Union Army. While here, the elder Holmes interacted with several local residents in Frederick and Middletown. One such was Gen. Edward Shriver (1812-1896) leader of the Potomac Home Brigade, who is buried in Mount Olivet's Area MM /Lot 23. Holmes first met him in Baltimore on the way here. He writes of him: "General Shriver, of Frederick, a most loyal Unionist, whose name is synonymous with a hearty welcome to all whom he can aid by his counsel and his hospitality. He took great pains to give us all the information we needed, and expressed the hope, which was afterwards fulfilled, to the great gratification of some of us, that we should meet again, when he should return to his home." The elder Holmes would write an account of his desperate search for his son and titled this "My Hunt After the Captain." It would appear in the December, 1862 edition of the Atlantic Monthly magazine, the same publication that later printed Whittier's "Barbara Frietchie" poem ten months later.  The elder Holmes would write an account of his desperate search for his son and titled this "My Hunt After the Captain." It would appear in the December, 1862 edition of the Atlantic Monthly magazine, the same publication that later printed Whittier's "Barbara Frietchie" poem ten months later. It has been said that Mr. Whittier borrowed some of Holmes' eye-witnessed imagery of Frederick for his own work since he, himself, had never been to Frederick. Holmes wrote the following upon laying eyes on Frederick while traveling on the National Pike (today's US40-A), just west of town on the eastern slope of Catoctin Mountain: "In approaching Frederick, the singular beauty of its clustered spires struck me very much, so that I was not surprised to find “Fair-View” laid down about this point on a railroad-map. I wish some wandering photographer would take a picture of the place, a stereoscopic one, if possible, to show how gracefully, how charmingly, its group of steeples nestles among the Maryland hills. The town had a poetical look from a distance, as if seers and dreamers might dwell there." Of course this vivid description could have given rise to the immortal opening stanzas by Whittier for his poem: "Up from the meadows, rich with Corn Clear in the cool September morn. The clustered spires of Frederick stand, Green-walled by the hills of Maryland." The rest is history as they say, because we have been known for those "clustered spires" ever since.  Oh, in case you were wondering, Capt. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. was found by his father in Hagerstown. Holmes, Jr. is one of the most widely cited and influential Supreme Court justices in American history, noted for his long tenure on the Court and for his opinions on civil liberties and American constitutional democracy—and deference to the decisions of elected legislatures. Holmes retired from the Court at the age of 90 in 1932. I recall seeing his face often as it was immortalized on a 15-cent postage stamp in my youth. George Leonard Andrews George Leonard Andrews (August 31, 1828 – April 4, 1899) was an American professor, civil engineer, and soldier. He was a brigadier general in the Union Army during the American Civil War and was awarded the honorary grade of brevet major general. During the Civil War, Andrews served in a number of important commands, first as the colonel of the 2nd Massachusetts, a regiment which saw heavy action in the Battles of Cedar Mountain and Antietam, among other actions. Mentored by Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks, Andrews became part of Banks's staff and was assigned several command roles in the Army Department of the Gulf during the later years of the war. From July through November, 1861, Lt. Col. Andrews was stationed in garrison here in Frederick as he and his troops were responsible for guarding the Upper Potomac under Maj. Gen. Banks. Robert Gould Shaw  Shaw and 54th Mass Memorial in Boston Shaw and 54th Mass Memorial in Boston One of the men that served with Lt. Col. Andrews and the 2nd Massachusetts was Robert Gould Shaw (October 10, 1837 – July 18, 1863). You may recall this Boston native for his later command of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. The Oscar-winning movie "Glory" tells Shaw's story as the young colonel was portrayed by actor Matthew Broderick in the 1989 motion picture release. Robert Gould Shaw spent plenty of time in, and around, Frederick with the 2nd Massachusetts in late 1861/early 1862. I wrote about him in a two-part "Stories in Stone" blog back in late February-early March, 2020. (I have included a link to those stories below.) Letters home to his sister Effie reveal the names of local citizens, some buried in Mount Olivet. The earlier-mentioned Edward Shriver was one of these as Shaw actually spent time at the former Shriver home located on N. Court Street, across from Court Square. Like Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., Shaw would be seriously wounded during the Battle of Antietam in September 1862. While recuperating back home in Massachusetts, he would be appointed to serve as Colonel of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. This happened in March 1863. Among the first units to be made up of African-American recruits, the 54th Massachusetts proved itself in an ultimately futile charge on Confederate earthworks near Charleston, South Carolina on July 18th, 1863. Shaw was buried in a mass grave with his men at Fort Wagner. Mount Auburn contains a cenotaph for Col. Robert Gould Shaw as this type of memorial is a monument to someone buried elsewhere, especially one commemorating people who died in a war. On this same trip, I saw the famous relief sculpture memorial for Shaw and his men of the 54th at Boston Common. This was sculpted in 1884 by Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Dorothea Dix Dorothea Lynde Dix (April 4, 1802 – July 17, 1887) was an American advocate on behalf of the indigent mentally ill who, through a vigorous and sustained program of lobbying state legislatures and the United States Congress, created the first generation of American mental asylums. During the Civil War, she served as a Superintendent of Army Nurses and was well-acquainted with Frederick as it served as "one vast hospital" throughout the conflict. Dix set stringent guidelines for nurse candidates. Volunteers were to be aged 35 to 50 and plain-looking. They were required to wear un-hooped black or brown dresses, with no jewelry or cosmetics. Miss Dix wanted to avoid sending vulnerable, attractive young women into the hospitals, where she feared they would be exploited by the male doctors as well as patients. She often fired volunteer nurses she hadn't personally trained or hired. All of these demands "earned the ire" of supporting care groups such as the United States Sanitary Commission, which Frederick's Dr. Lewis Henry Steiner (1827-1892) headed during the war. Dr. Steiner is buried in Mount Olivet's Area G/Lot 85. You can learn more about Dorothea Dix at our local National Museum of Civil War Medicine on East Patrick Street. In my earlier research on Barbara Fritchie, author John Greenleaf Whittier reported that Miss Dix was one of his trusted sources for the September flag-waving incident with the Rebel horde in September, 1862. Caroline Healy Dall Caroline Wells Dall (née Healey; June 22, 1822 – December 17, 1912) was an American feminist writer, transcendentalist, and reformer. She was affiliated with the National Women's Rights Convention, the New England Women's Club, and the American Social Science Association. Her associates included Elizabeth Peabody and Margaret Fuller, as well as members of the Transcendentalist movement in Boston.As a young woman, she received a comprehensive education, encouraged by her father to write novels and essays, and to engage in debates about religion, philosophy and politics. In addition to private tutoring, she attended a private school for girls until the age of fifteen. Ms. Dall came to Frederick in the 1870s in search of the truth about Barbara Fritchie and her alleged confrontation with Stonewall Jackson during the Civil War. She spoke to Dorothea Dix and numerous Frederick townspeople and Barbara Fritchie associates while conducting her "investigation." Of those included were the abovementioned Dr. Lewis H. Steiner, diarist Jacob Engelbrecht, former mayor Valerius Ebert, store-owner/author Henry Nixdorff, niece Catherine Hanshew and Marie Diehl, instructor at the Frederick Female Seminary and daughter of former Evangelical Lutheran Church Rev. George Diehl. All but Ms. Diehl are buried in Mount Olivet. Miss Dall's writings on Barbara Fritchie appeared in newspapers, magazines and was published in hardback form in 1892 as Barbara Fritchie; A Study. At the end of the work, Ms. Dall makes mention of Mount Olivet, but not by formal name: "It was a sunny Sabbath afternoon when a few days later I drove out over South Mountain. Braddock's Road crossed mine almost at a right angle. A spring is still shown where his men stopped to drink. The hillsides are covered with chestnuts hung with vines. From the latter the Germans make a very fair claret. from the cemetery where Francis Key's body was laid, one may look far down the road which leads to Washington. It is a broad highway, traversing the distance with a mighty sweep. As I looked, I felt the poet's dry bones must have put on their flesh when the Rebel army marched into Frederick! Old Duvall, who had charge of the cemetery, had been on the spot all through the war. He saw Burnside enter, the sun gleaming on his bayonets, cavalry skirmishing along the road, and the artillery shells from the rear over both armies. I could see it all as I listened and looked down the turnpike, threading the beautiful hills on the way to Georgetown! When you are on the spot, Harper's Ferry also seems to be only a suburb of Frederick. Certainly, John Brown and dear old Barbara have long since shaken hands!" Dall was referring to Mount Olivet's first superintendent, William T. Duvall (1813-1886). Her book subject's body was not here at that time, as she had been originally buried at the Old German Reformed Burying Ground on the west side of town (at the corner of West Second and North Bentz streets). This is today's Memorial Park. Barbara Fritchie would be re-interred in Mount Olivet in 1913, just five months after Ms. Dall's death. Felix O. C. Darley Felix Octavius Carr Darley (June 23, 1822 – March 27, 1888), often credited as F. O. C. Darley, was an American illustrator, known for his illustrations in works by well-known 19th-century authors, including James Fenimore Cooper, Charles Dickens, Mary Mapes Dodge, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Washington Irving, George Lippard, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Donald Grant Mitchell, Clement Clarke Moore, Francis Parkman, Harriet Beecher Stowe and Nathaniel Parker Willis. I've seen plenty of Civil War scenes illustrated by Mr. Darley, but this is overwhelmingly my favorite. Some of those featured above may be new names to us Marylanders, but certainly were well-rooted and known in the greater Boston area. However, my favorite decedent, whose grave I visited on this particular July day at Mount Auburn, was that of an individual likely unknown to Massachusetts historians and genealogists. That said, many former local residents, now buried in Mount Olivet, knew her well during her lifetime which began in Frederick City nearly a century and a half ago. This was Nellie Cole, known after marriage as Pauline (Cole) Knissell (1876-1956). So here I will attempt to give you, the reader, a reverse-engineered “Story in Stone” about a former Fredericktonian turned permanent “Mount Auburnian” for eternity. Before departing Frederick, I conducted a number of web search trials looking for someone from Frederick who is buried at Mount Auburn. I finally came upon one in the aforementioned Ms. Knissell. I immediately researched her genealogy and found her parents and many siblings here in Mount Olivet. Her maiden name of Cole is a popular one around our parts, and her parents, Charles Edwin Cole (1847-1905) and Mary Catherine (Nichols) Cole (1851-1901), are buried in Mount Olivet’s Area R/Lot 140. In this same plot, I found Nellie’s brother, George William “Will” Cole (1886-1961). In addition, other siblings are buried here too, including Frank Warehime Cole (1882-1962) in Area AA/Lot 56; Clara May (Cole) Weller (1873-1944) in Area Q/Lot 140; and Charles Edward “Ed” Cole (1870-1935). This last gentleman worked as a linotype operator in the composing department of the Frederick News-Post for the majority of his life. I suddenly realized that I had interviewed this man’s grandson, Louis N. Cole, Jr., for a documentary project about the newspaper. This was in the early 1990s, and Mr. Cole had recently retired after working the same job in the composing department for his career, as his father (and grandfather) before him. These gentlemen are buried here in Mount Olivet as well and constitute a brother, nephew and grand-nephew of our subject (buried in Mount Auburn), Ms. Knisell. To learn more about the Cole family, I was tremendously aided by a family historian named Connie Houtz. Ms. Houtz has done incredible work detailing family members with biographies, obituaries and photographs on the popular site Find-a-Grave.com. Most all of the Cole family photos in this story are from Connie's collection. I first was made aware of her genealogical prowess while publishing a blog in this series titled “Eyewitnesses to the Battle of Monocacy.” In that story, I talked about families buried here in Mount Olivet who played pivotal roles in the July, 1864 "Battle that Saved Washington." In particular, one gentleman was the paternal uncle of our subject, Nellie, in the form of William G. Cole (b. 1815 in York, PA). He served as mayor of Frederick during the American Civil War, and is best remembered for delivering the $200,000 ransom demanded by Confederate Gen. Jubal Early. This was done to thwart any potential damage or destruction to the “clustered-spired” city. Information on Nellie Pauline (Cole) Knisell is scarce. I at least wanted to check her cemetery records. I was aided (onsite) by Mount Auburn’s Client Relations Coordinator, Caitlin Lowry Zouras, in pulling any information the cemetery had pertaining to the Knisell family lot , No. 8429, on Mount Auburn’s Birch Avenue. The Lot card was in a bank of file cabinets located just a few feet from Ms. Zouras' desk. From this exercise, I learned that there are five decedents buried on the lot under one central stone. Of particular interest was the fact that the date of purchase was May 3rd, 1950, and more so, that there existed a joint-ownership between Nellie Pauline and her sister, Mary Rebecca “Mayme” Cole (1889-1967). Now I had not just one, but two former Fredericktonians in Mount Auburn with Nellie and “Mayme.” Nellie Pauline’s husband, Edward Leavitt Knisell (1876-1969) is buried in the plot along with a daughter, Sarah Katherine (Knisell) Wheeler (1902-1995), and Sarah’s infant child, Douglas Robert Wheeler, who died in January, 1959 just 11 hours after his birth. Again, my sincere thanks to Connie Houtz who illustrated corresponding Find-a-Grave pages of these family members with photographs so I could put faces with names at real time speed. She also helped shed light on the girls’ upbringing here in Frederick through an extensive biography on their father, Charles Edwin Cole. Here is what she included on the Find-a-Grave memorial page for this man: Charles Edwin Cole was a printer by trade, having learned the trade with his father, Charles E. Cole, who published the Maryland Union in Frederick, Maryland until his death in 1882. After his father's death, Charles was a compositor on the Examiner until 1903 when he was obliged to retire due to failing health. He was a nephew of William G. Cole, who was Mayor of Frederick from 1859 to 1865 during the Civil War. Charles married Mary Catherine Nichols of Frederick on 26 November 1869. They were married by the Rev R. Hinkle. Charles was a life-long resident of Frederick, living at 22 East 5th Street, and a member of the Evangelical Lutheran Church and of the Junior Steam Fire Engine Company. He was known for his sterling character and kind and congenial disposition. Nellie's mother, Mary C. (Nichols) Cole, died on June 5th, 1901. Her husband would die four years later in late summer of 1905. Both would be buried here in Mount Olivet's Area R as I mentioned earlier. From deciphering interment records at Mount Auburn, I found that Nellie Cole was born on July 22nd, 1876. I found her in the 1880 Census living at the family home at 22 East 5th Street, now the site of modern condominiums. I don’t know how, or when, Nellie met her husband, Edward L. Knisell, but the couple married at Nellie's home on November 30th, 1899 by Frederick’s Evangelical Lutheran Church minister. She can be found in the 1900 US Census living in Glassboro, New Jersey with her husband’s family. Fittingly, Edward worked for a glass company as an assistant secretary. From a few later records, I found that Edward was employed by the Cape May Glass Company. The couple obtained their own home by 1910, in neighboring Pitman, NJ to Glassboro. They moved to the Boston area by the 1910 census. Nellie and Edward had three children, but only two reached maturity. These included son Leavitt (1900-1981), daughter Sadie "Sarah" Katherine(1902-1995) and another child, Pauline, who died in her first year (1908-1909). Pauline is buried in Glassboro, NJ. I’m assuming that Edward’s job would eventually take the family to Massachusetts as the Knisells can be found there in 1918. A draft registration card for Edward gives his employment as a sales manager for the Cape May Glass Company located at 40 Battery Ward in Boston. This likely may be the upscale Battery Wharf area of today. The Knisell's home residence is listed as 48 Edison Green in the Dorchester suburb of south Boston.  Trio of Yeomanettes during WWI at Charlestown Navy Yard Trio of Yeomanettes during WWI at Charlestown Navy Yard The 1920 Census shows Nellie and her family still living on Edison Green. An additional tenant residing with them is Mary Rebecca Cole (aka Mayme). Mayme is 30 years of age at this time and her job is given as working for the Paymaster Department of the Navy Yard. I would learn that this was the Charlestown Naval Yard in north Boston. Years later, her obituary mentions that she was the Chief “Yeomanette” of that facility. What's a "yeomanette?" The first large-scale employment of women as Naval personnel took place to meet the severe clerical shortages of the World War I era. The Naval Reserve Act of 1916 had conspicuously omitted mention of gender as a condition for service, leading to formal permission to begin enlisting women in mid-March 1917, shortly before the United States entered World War I. Nearly six hundred Yeomen (Female) were on duty by the end of April 1917, a number that would grow to over 11,000 in December 1918, shortly after the Armistice. The Yeomen (F), or "Yeomanettes" as they were popularly known, primarily served in secretarial and clerical positions, though some were translators, draftsmen, fingerprint experts, ship camouflage designers and recruiting agents. We have four know "Yeomanettes" buried in Mount Olivet, including the last living veteran of this rank from World War I in Charlotte (Berry) Winters (1897-2007). The Knisells moved to Watertown, Massachusetts before 1930 and can be found living at 258 Common Street. The house still stands and is less than two miles west off Mount Auburn. Sarah had married by this time, however son Leavitt and Nellie’s sister Mary were still living with the family. Nellie continued to keep house, while Edward remained working in the glass industry, now as a “commercial traveler,” which I’m assuming is the same as a traveling salesman. It appears from the 1940 census that son Leavitt is a salesman for the same glass firm his father was working for. Meanwhile, Mayme Cole was a stenographer at the Naval Base located in north Boston. I would find a few blurbs in the Frederick newspaper of occasional visits by Knisells to Frederick to see family. I’m sure she returned to Frederick and visited Mount Olivet for the funeral of her older sister, Clara May (Cole) Weller (b. 1873) in September, 1944. The 1950 Census shows the family still living in Watertown on Common Street. Leavitt has moved on, but daughter Sarah Katherine is living here with son Robert after her divorce from Robert Southwick Wheeler, Jr. Mayme is residing with them and Edward, at 73, was still employed as a glass salesman. Nellie passed away on January 15th, 1956. Her body would be brought to the Mount Auburn lot, #8429 on Birch Avenue, which she had purchased six years prior. A small article appeared in the January 24th edition of the Frederick News-Post saying that family members traveled to Boston for the funeral. Mary R. “Mayme” Cole retired from the Charlestown (Massachusetts) Navy Yard in 1955 and continued to live with Edward after her sister’s death. She died May 4th, 1967 at the age of 77 and was remembered with quite an obituary. Ms. Cole would be buried next to Nellie in the lot on Birch Avenue. As for Edward Leavitt Knisell, he outlived his wife by 13 years, dying on February 18th, 1969. Interestingly, he would live out his life right here in Frederick, but his body would make the trip to Massachusetts and Mount Auburn for burial. The story of these Cole sisters may not be one of the most riveting in this blog series, but it features several threads that bind us to Mount Auburn, the legendary rural/garden cemetery upon which Mount Olivet was modeled. If you are in the Boston area on pleasure or business, I strongly urge you to make time for a visit. You won’t be disappointed. Of course, feel free to visit the Cole sisters' parents in Mount Olivet's Area R/Lot 152 at anytime. If life had worked differently, they, perhaps, would be resting here in death. AUTHOR'S NOTE: Special thanks to Connie Houtz and Mount Auburn's Curator Meg Winslow and the kind staff of Mount Auburn Cemetery for their assistance with this "Story in Stone."

0 Comments

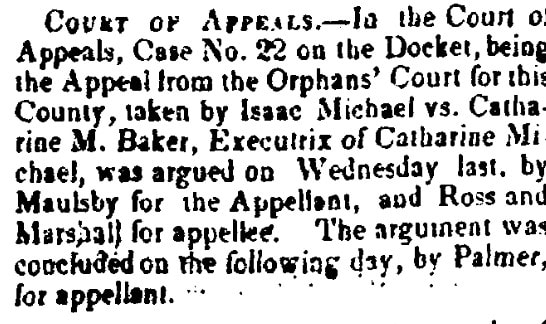

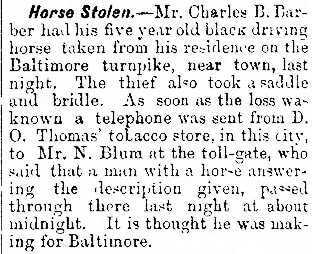

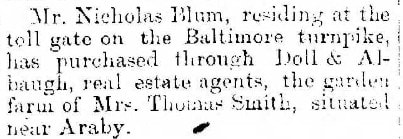

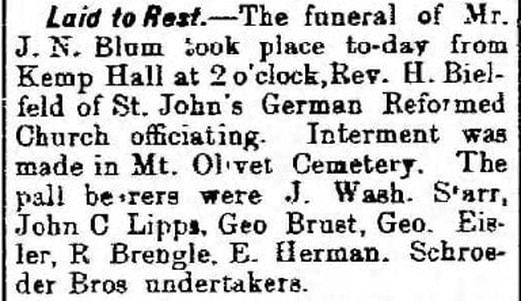

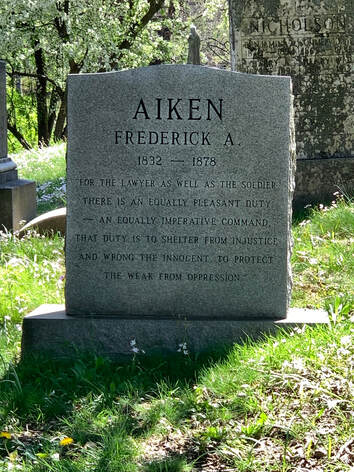

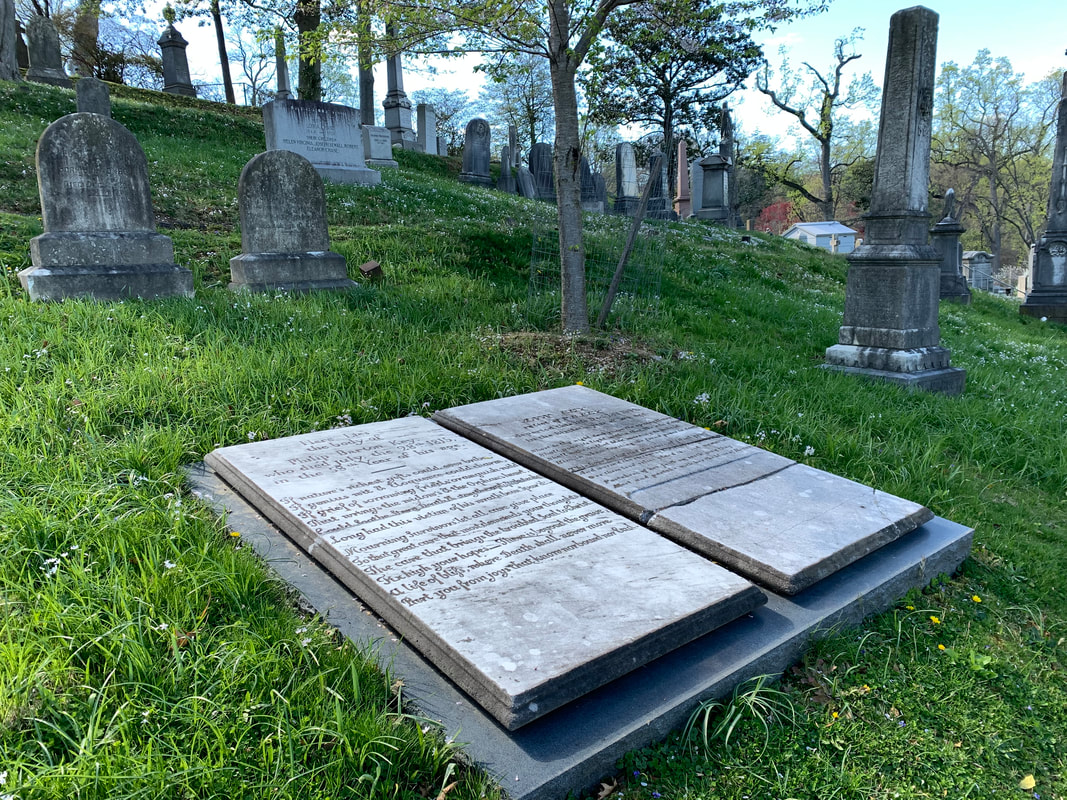

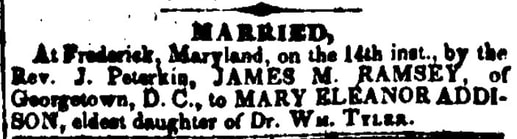

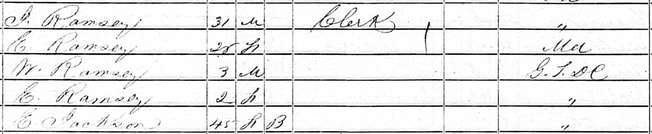

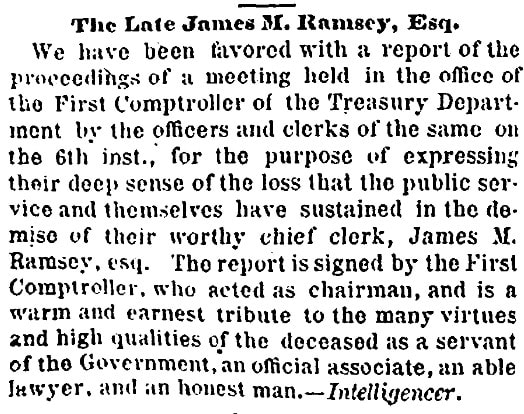

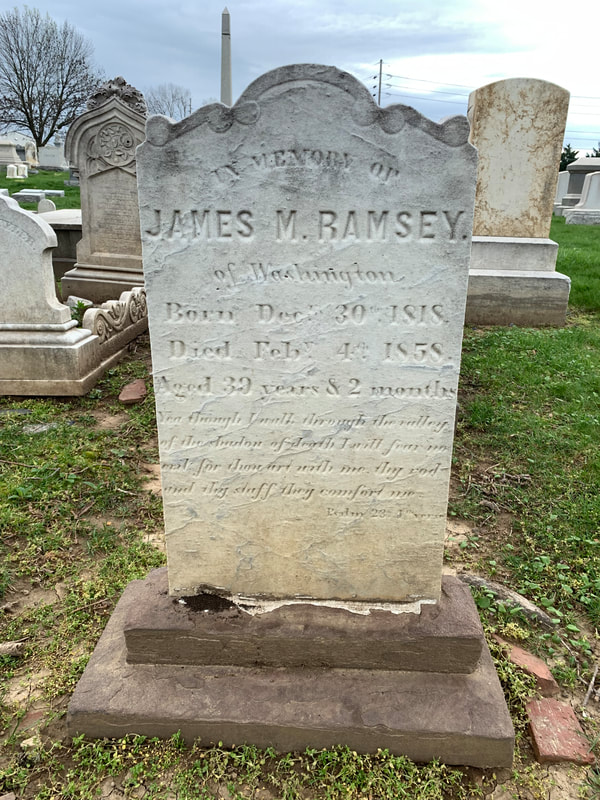

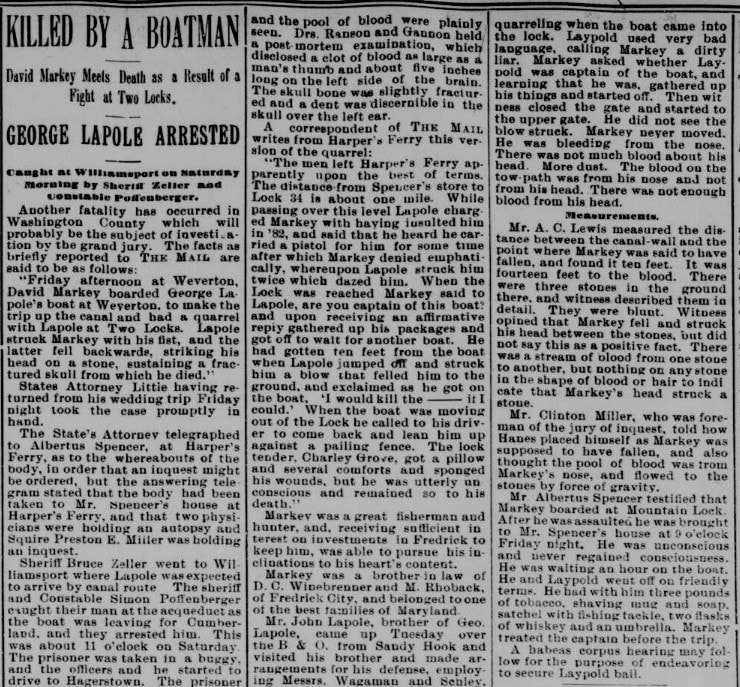

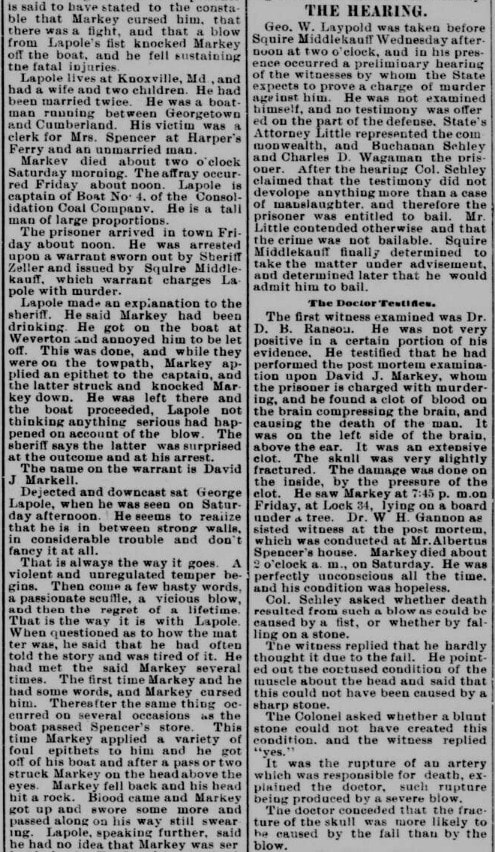

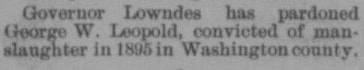

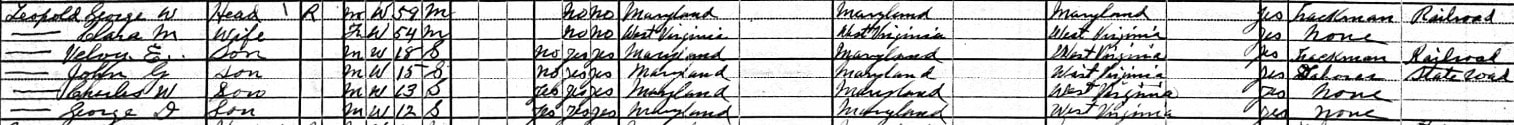

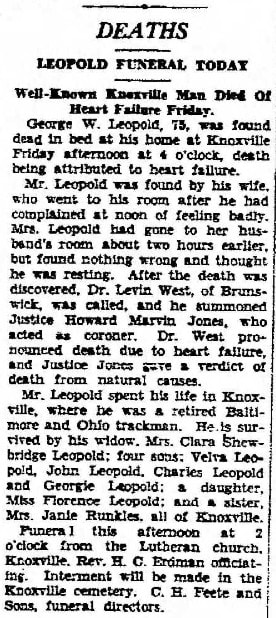

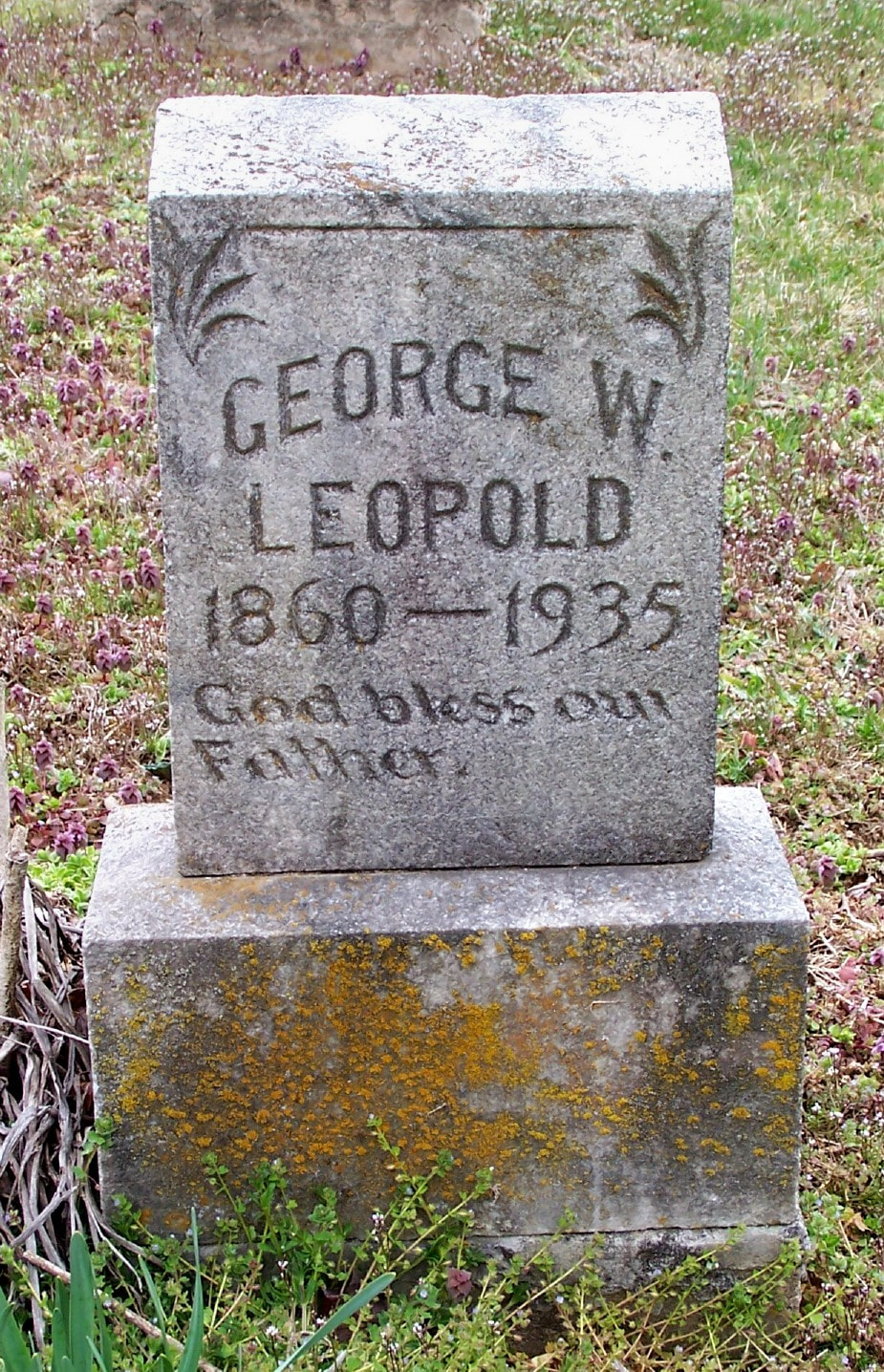

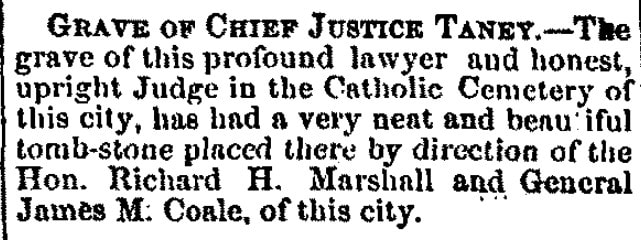

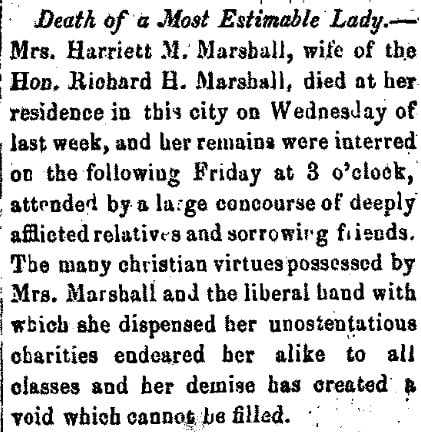

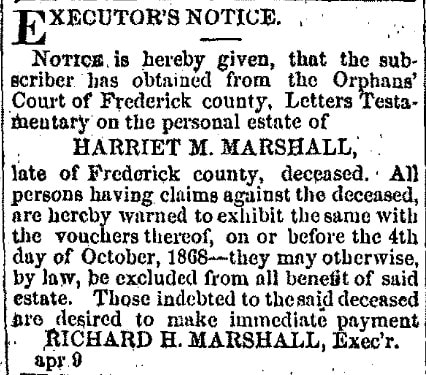

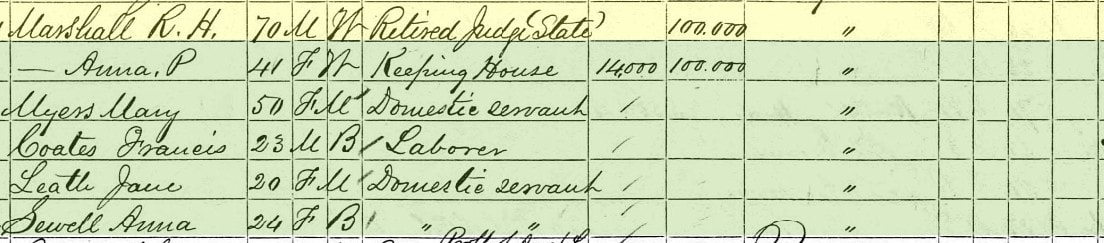

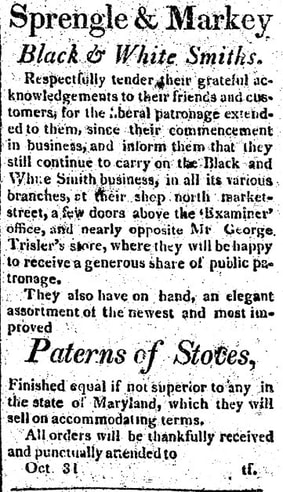

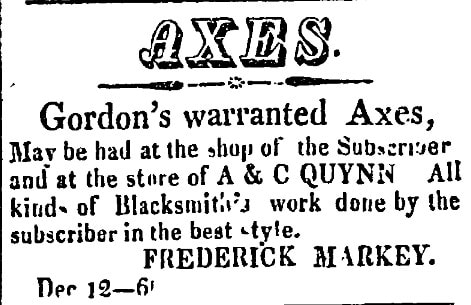

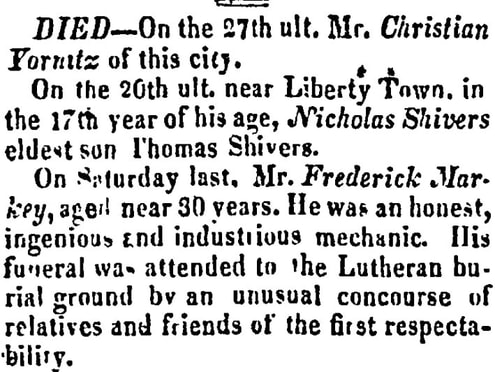

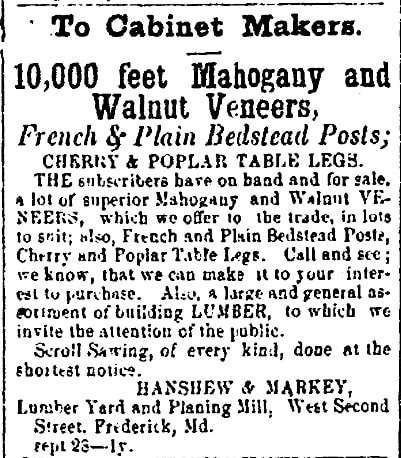

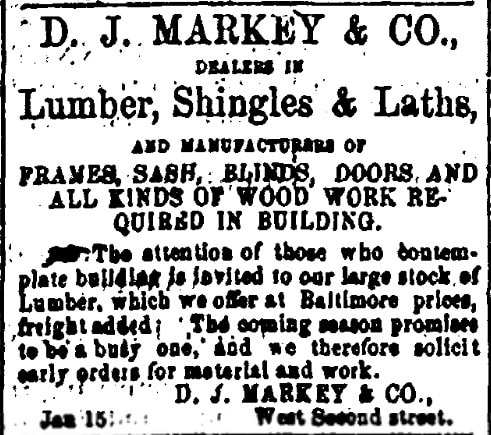

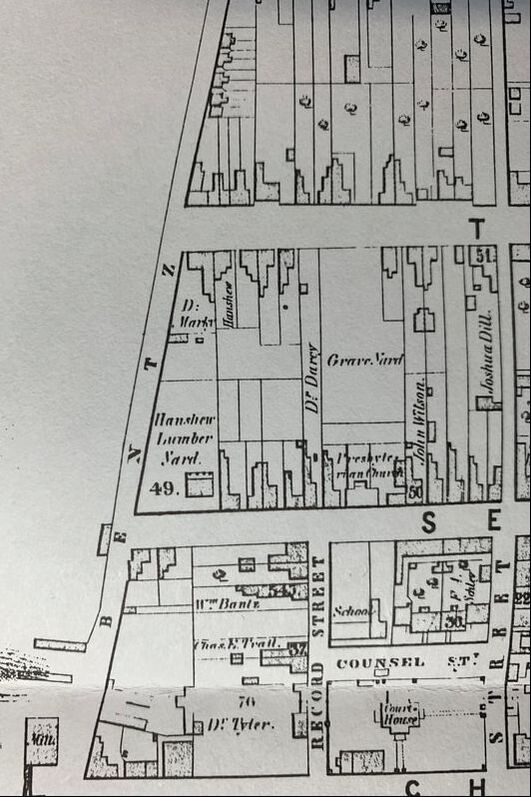

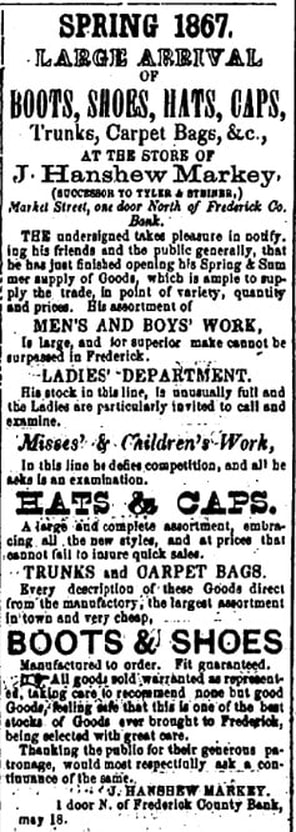

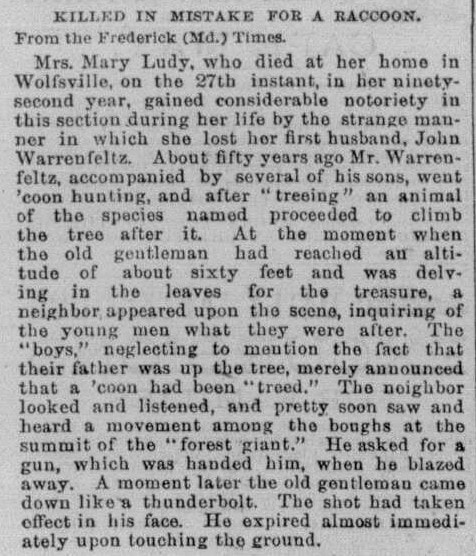

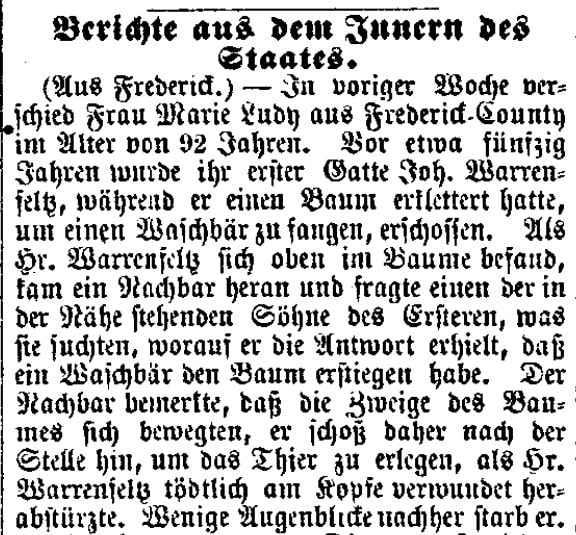

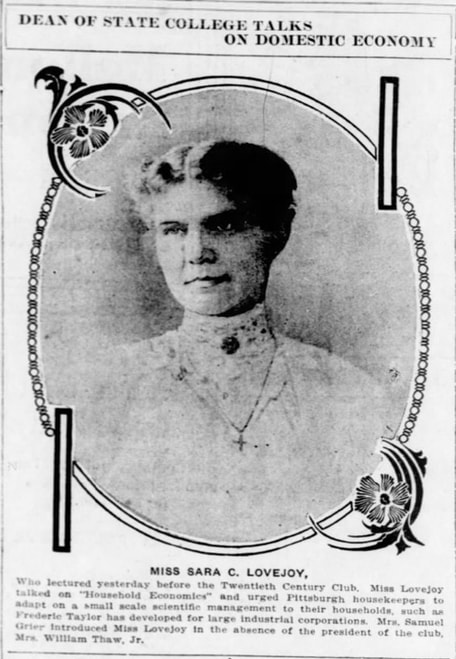

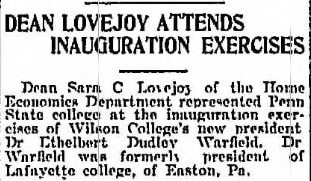

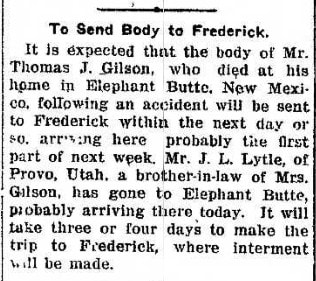

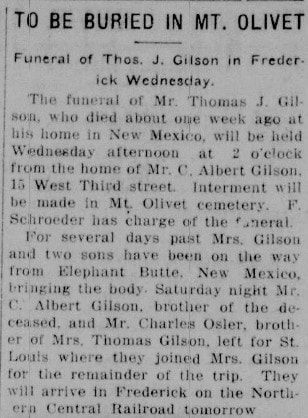

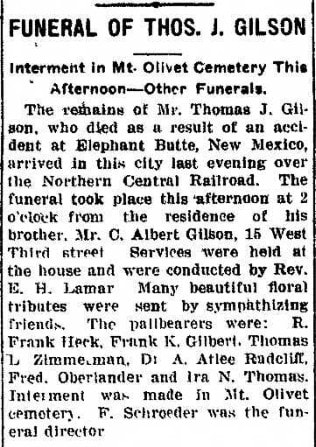

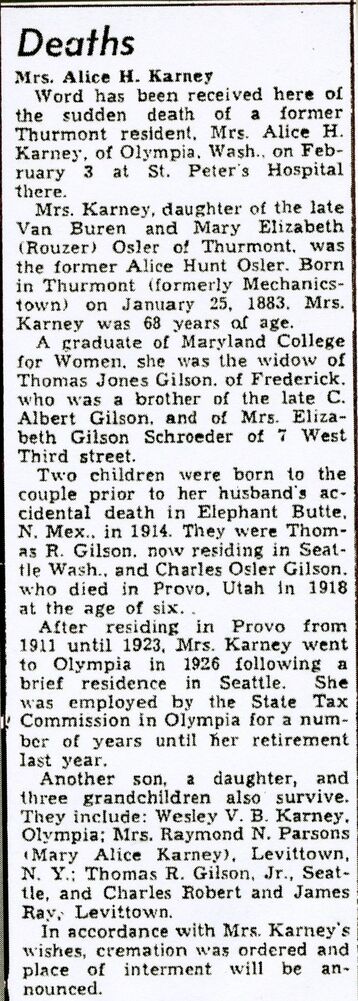

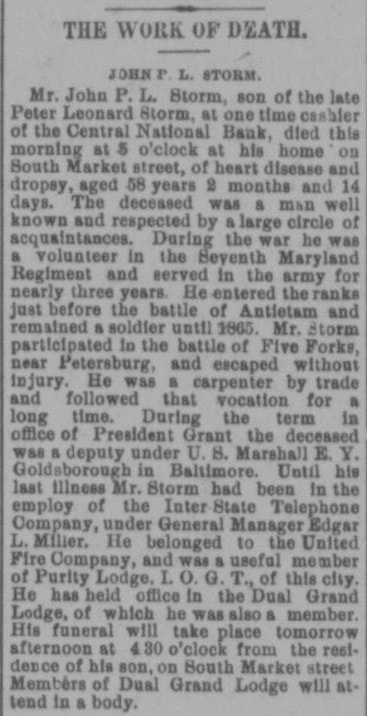

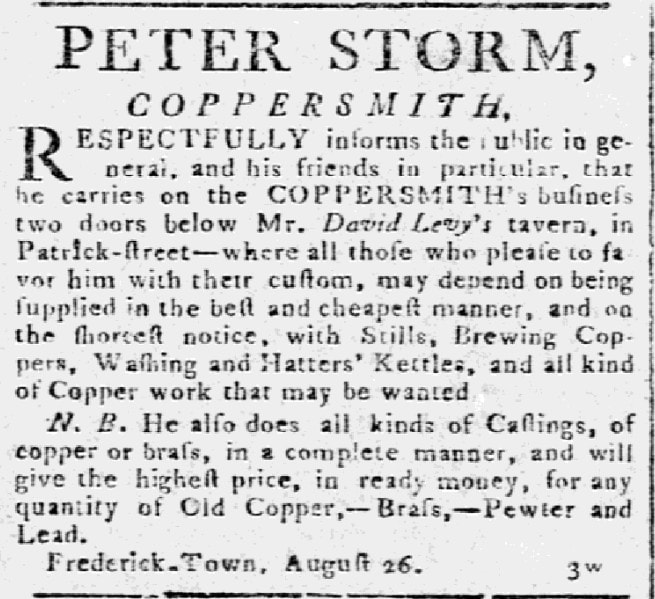

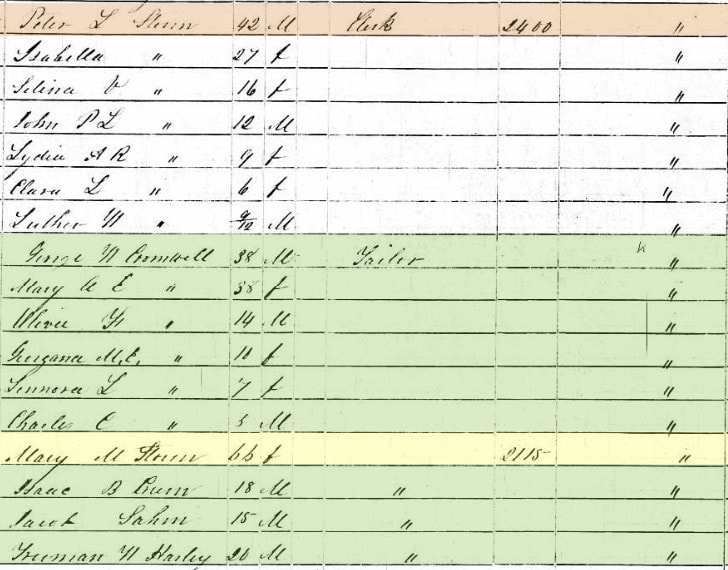

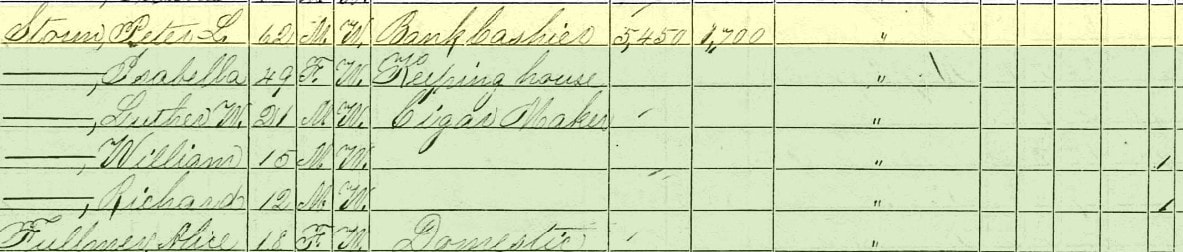

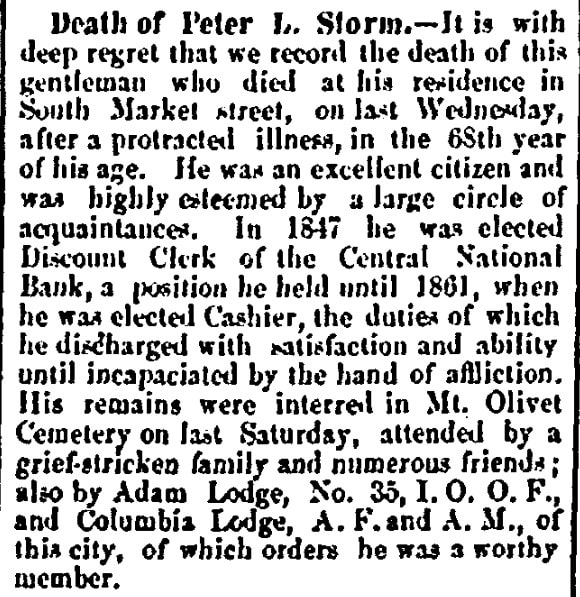

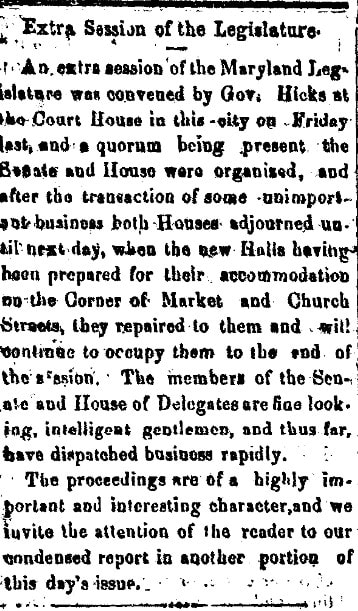

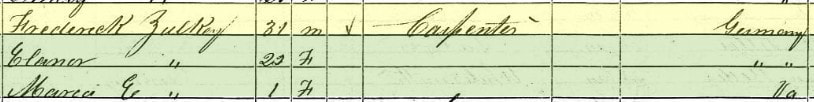

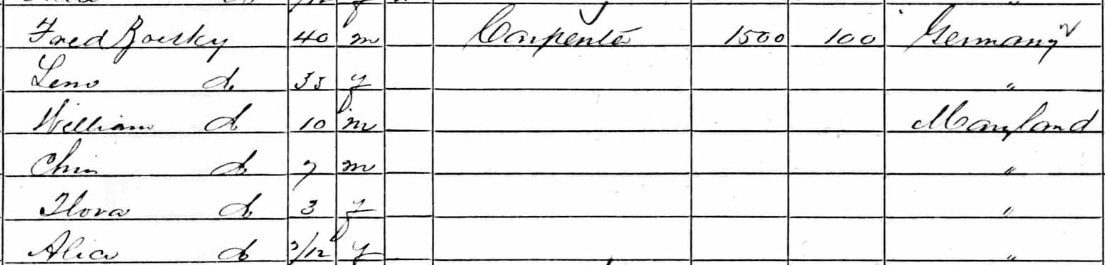

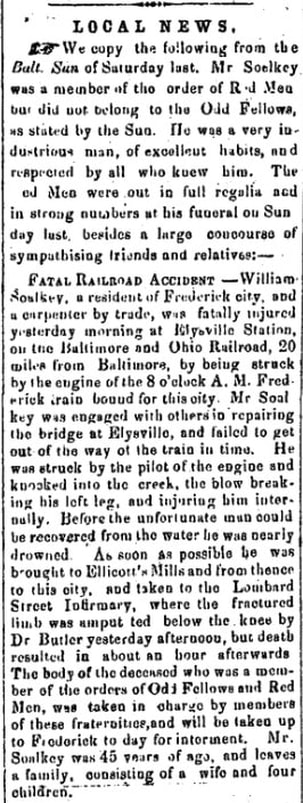

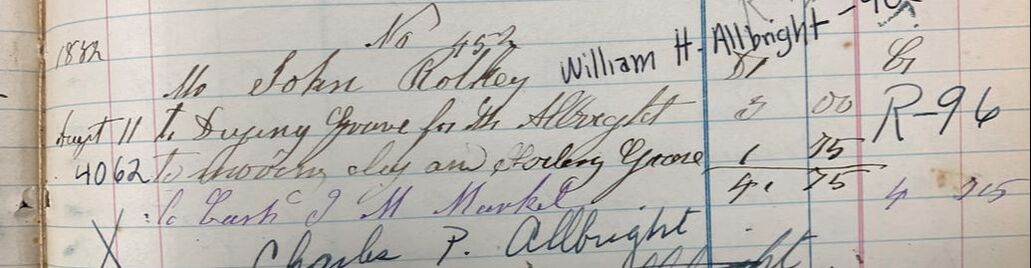

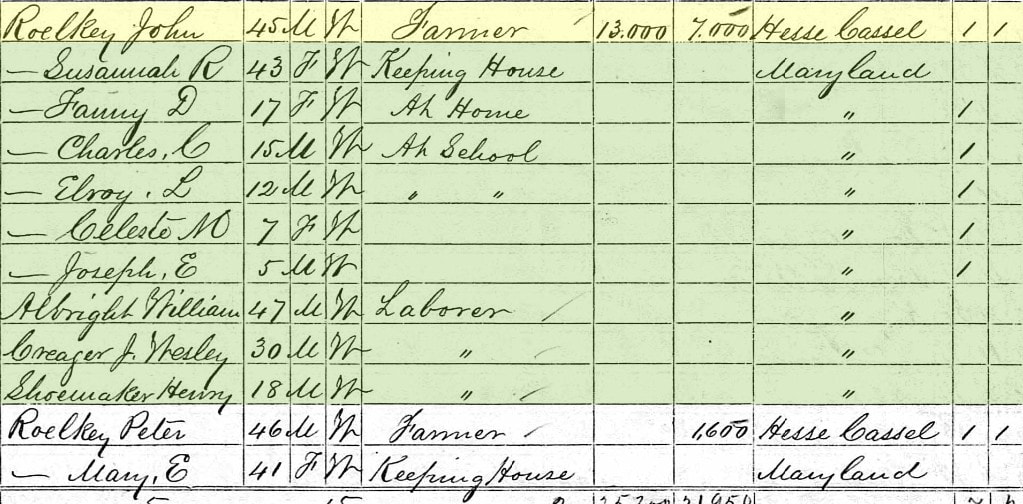

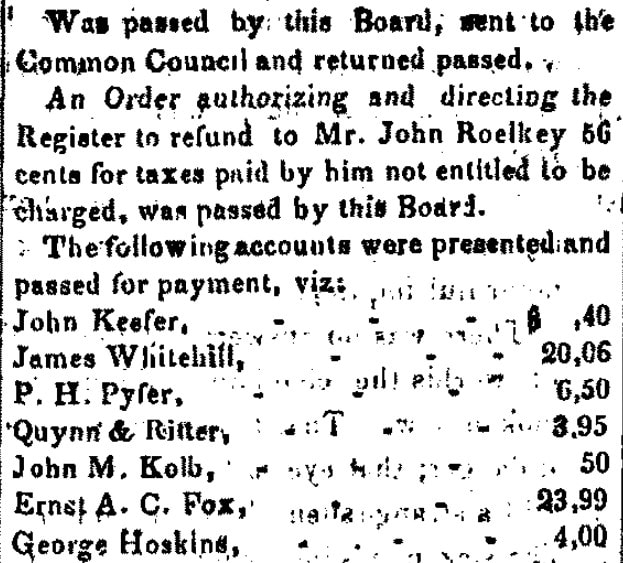

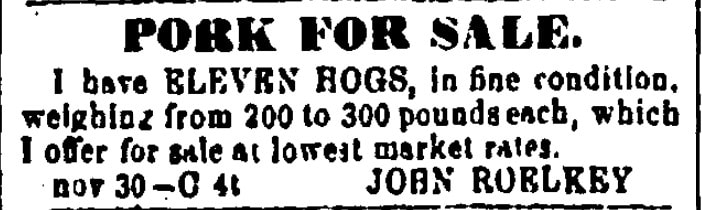

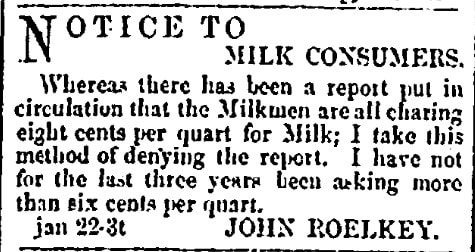

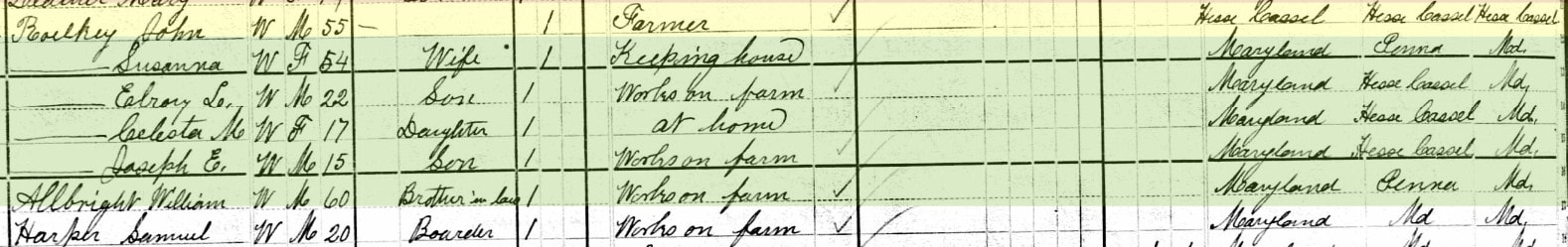

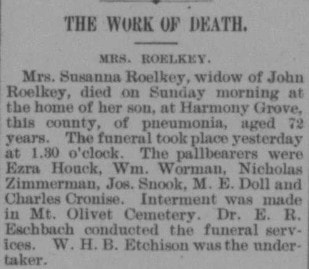

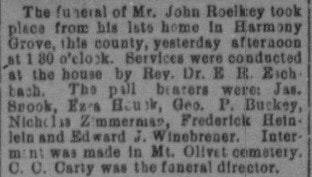

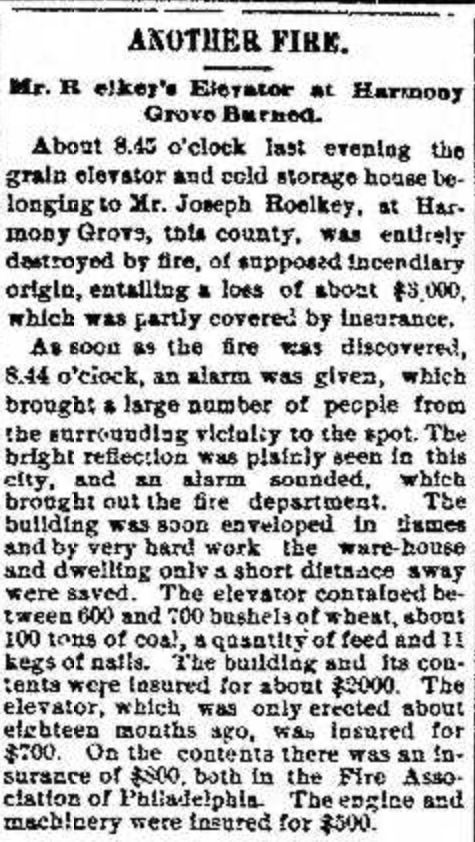

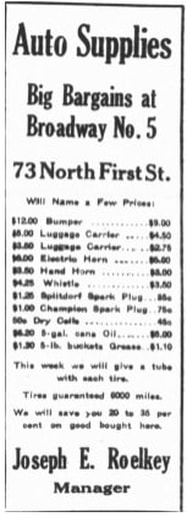

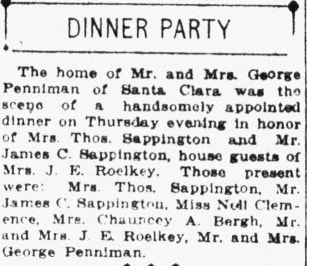

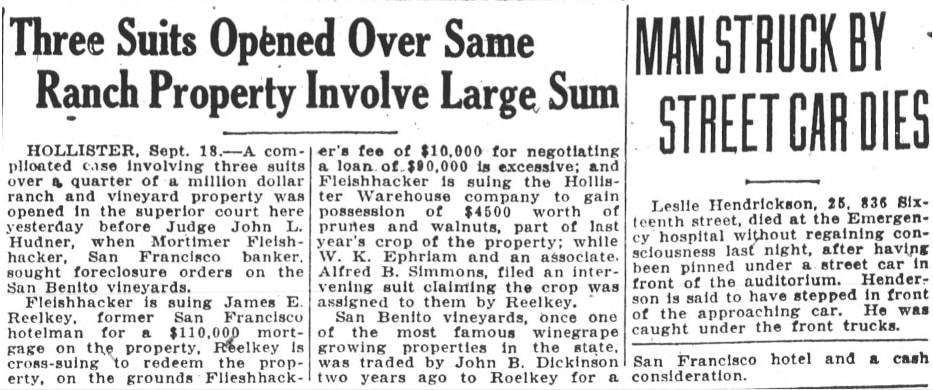

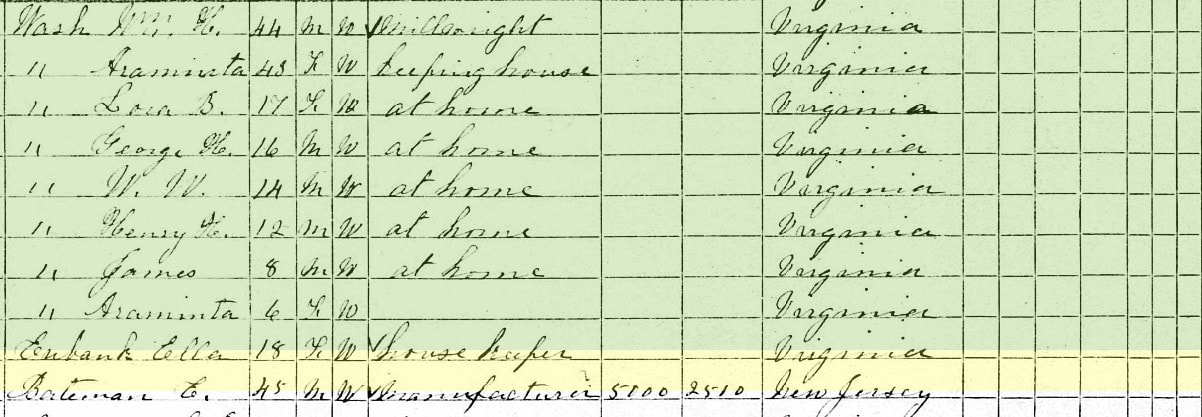

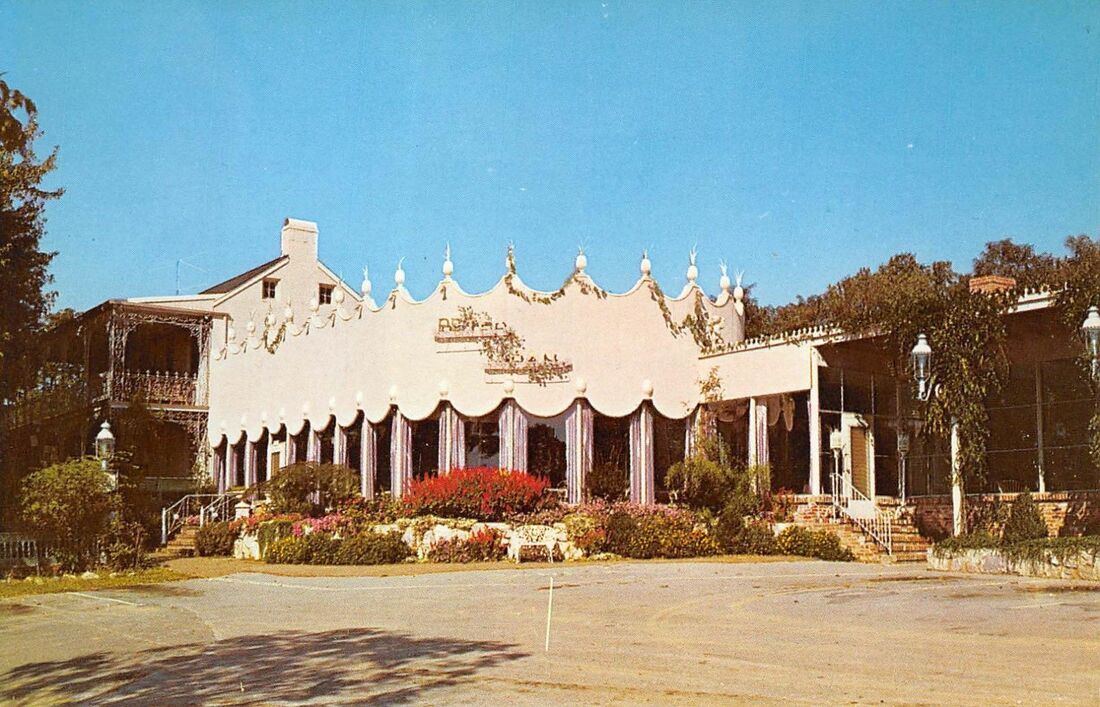

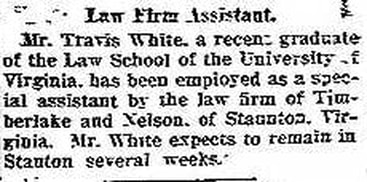

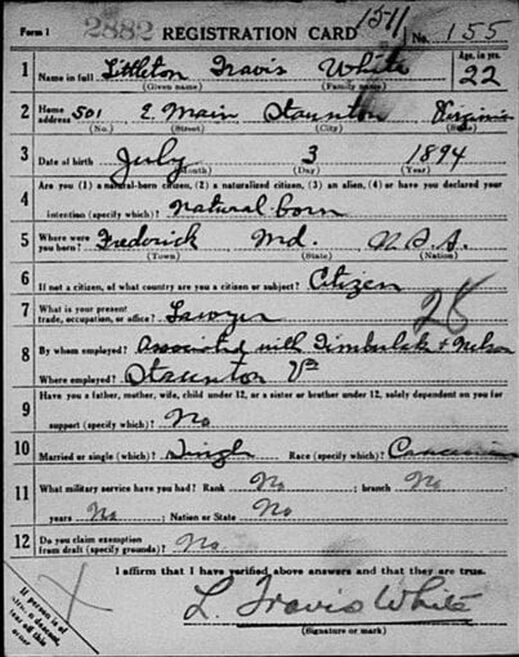

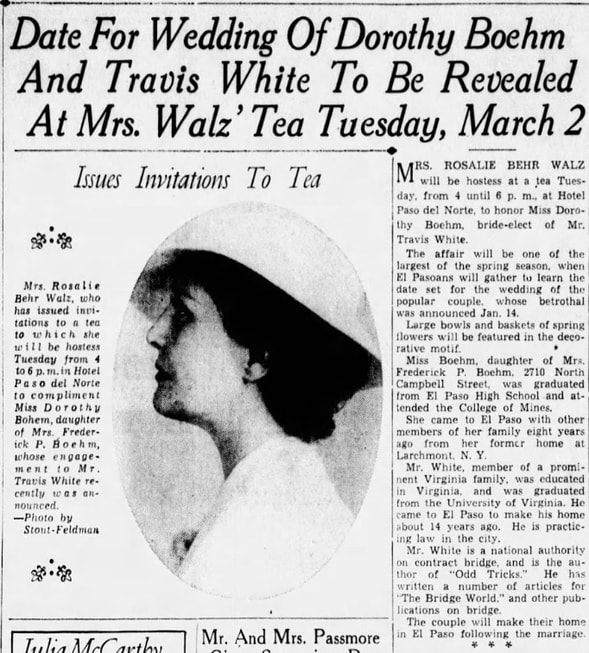

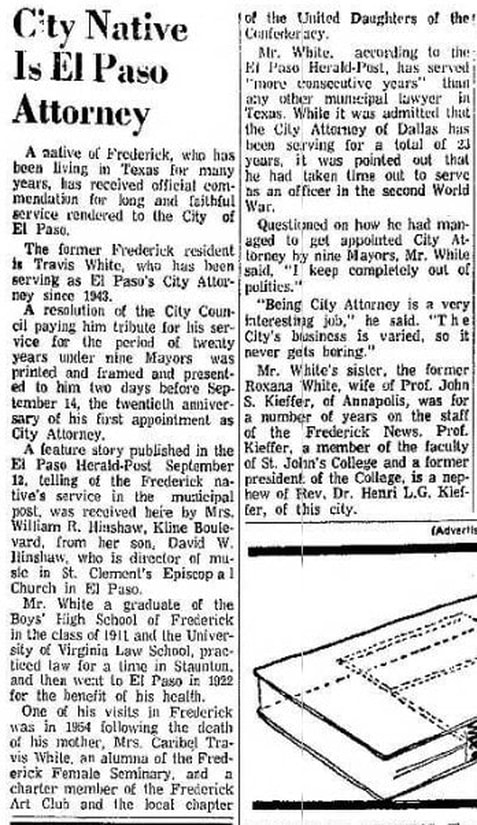

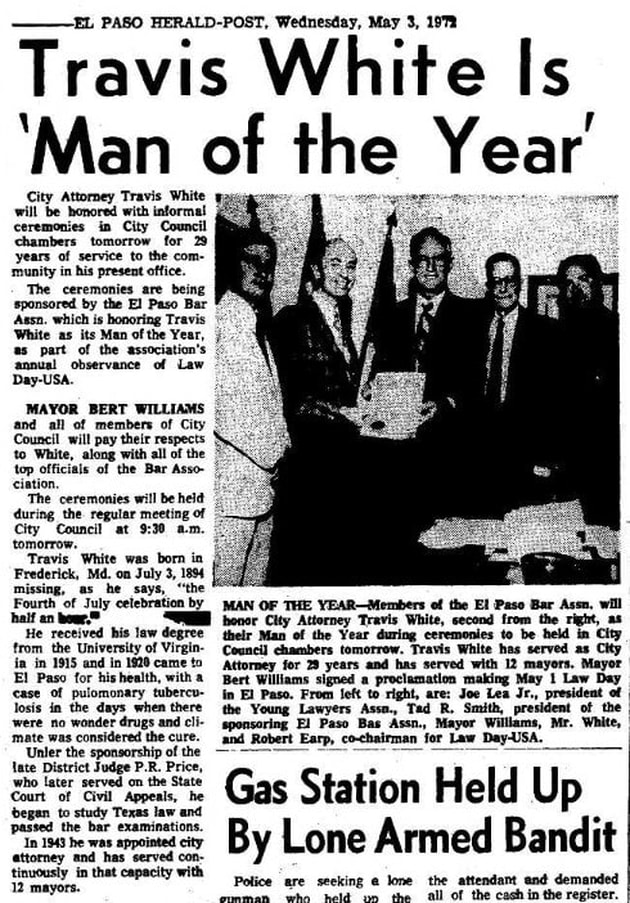

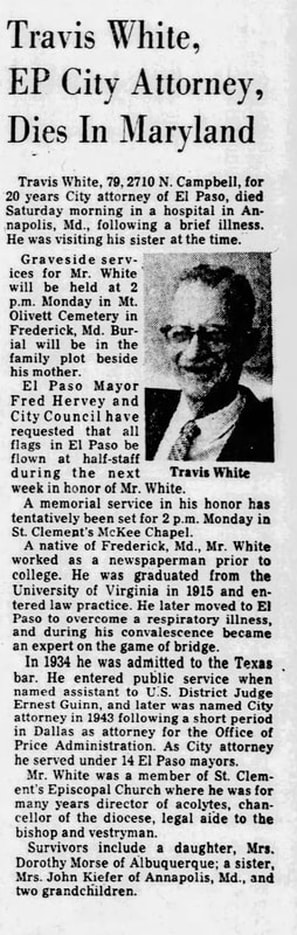

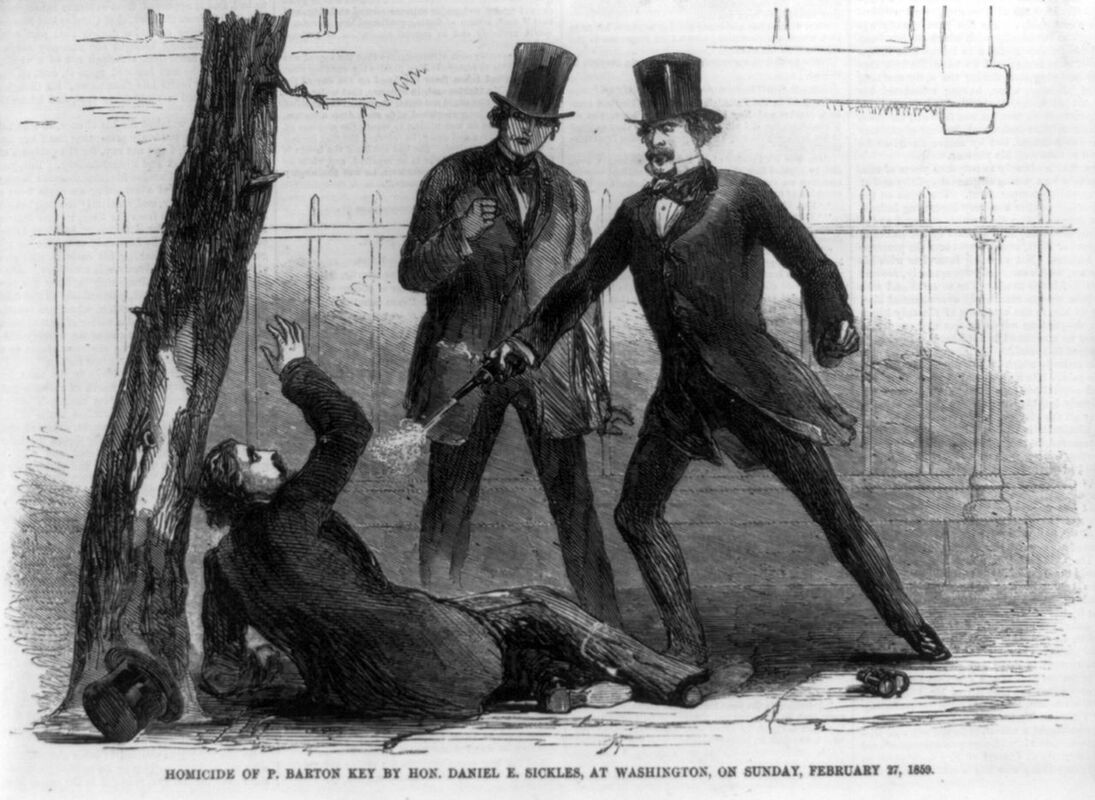

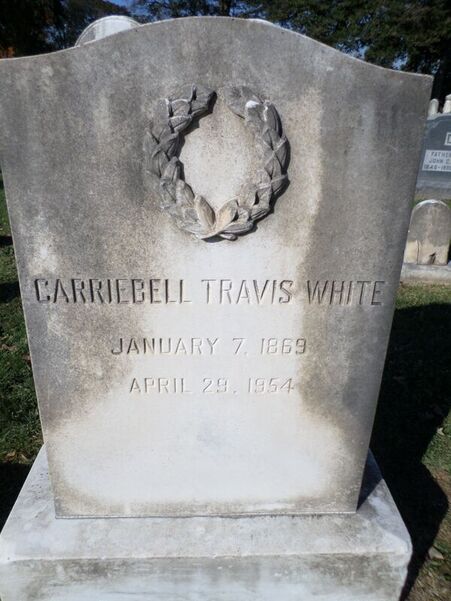

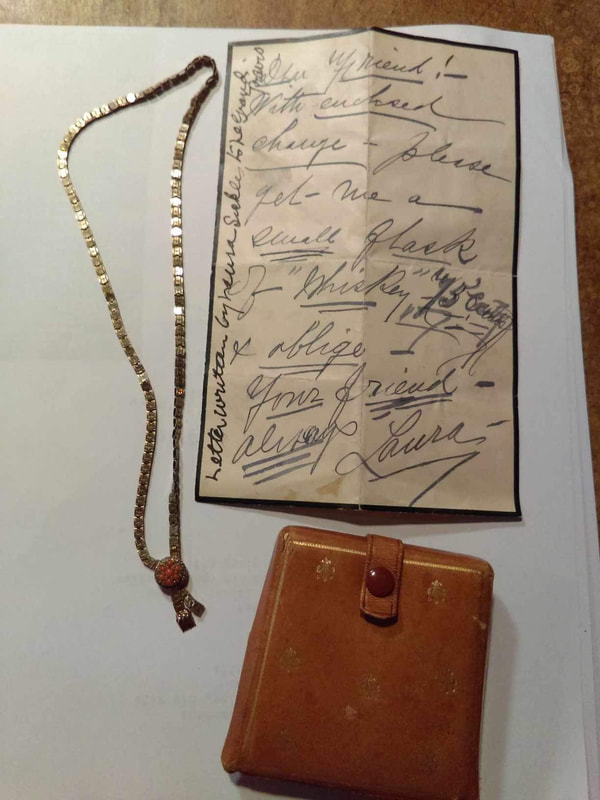

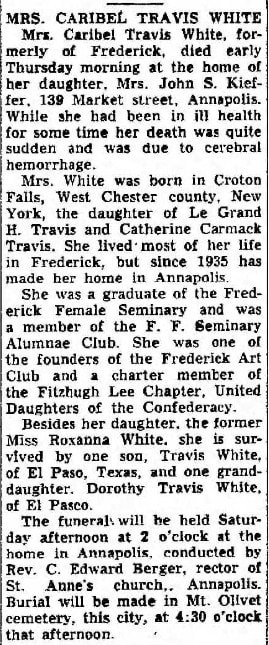

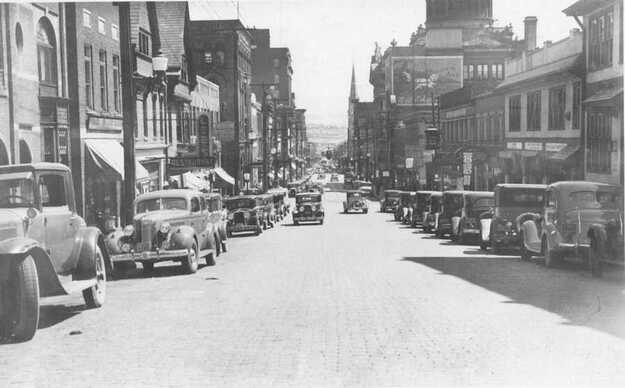

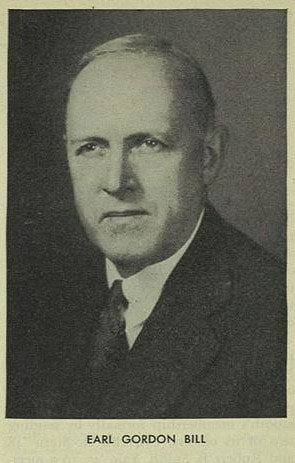

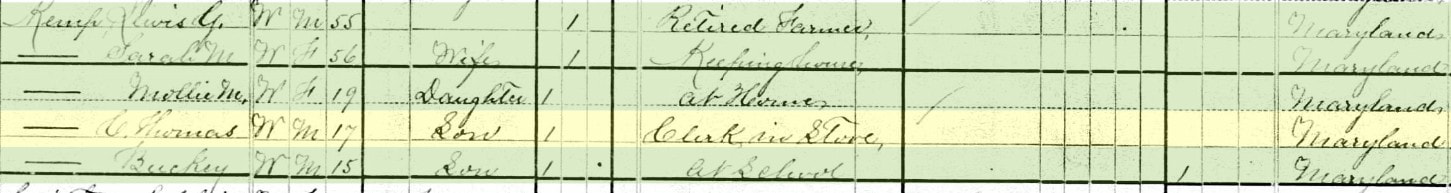

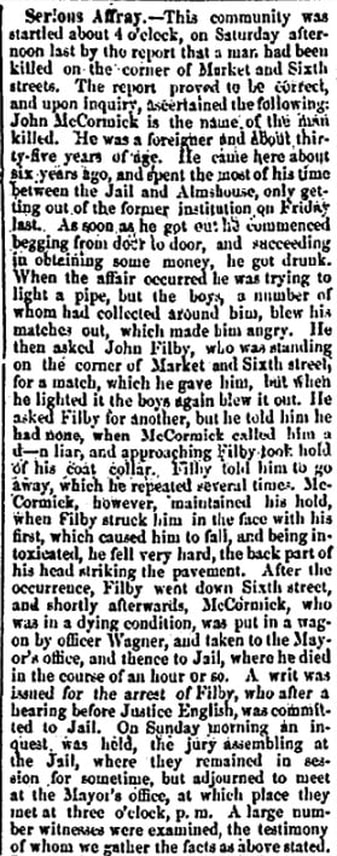

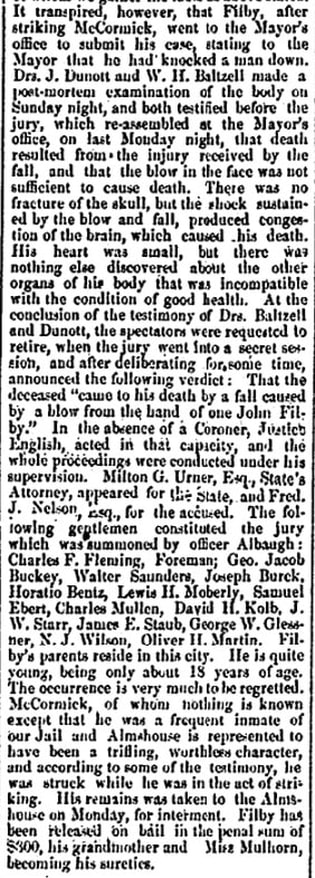

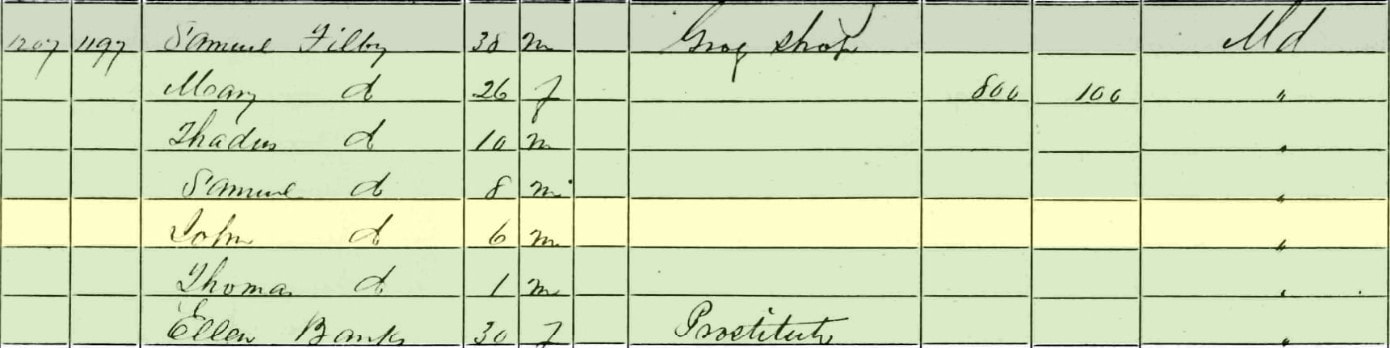

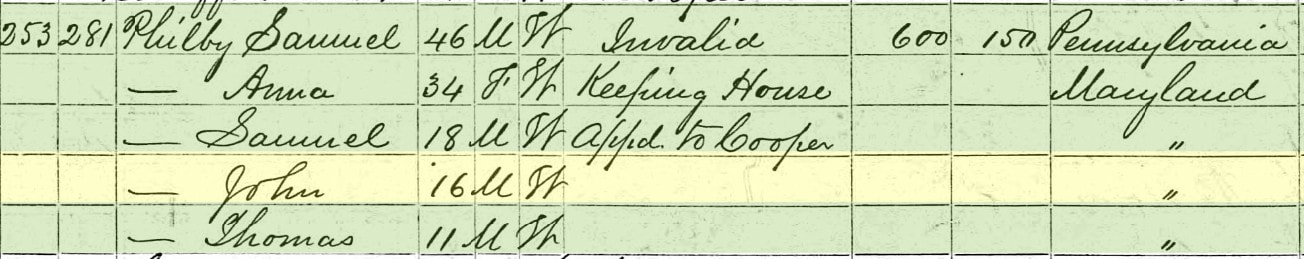

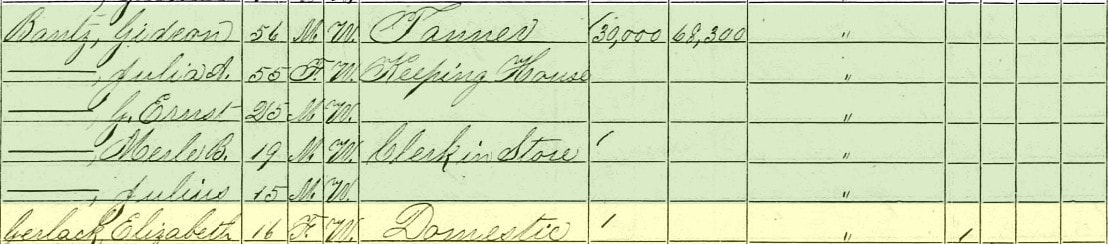

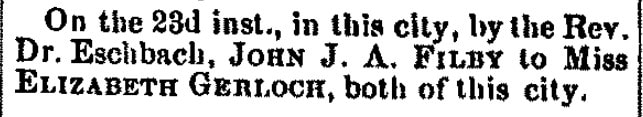

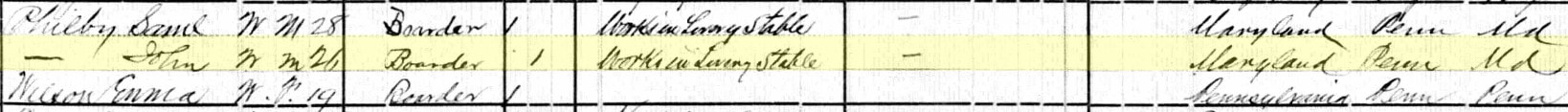

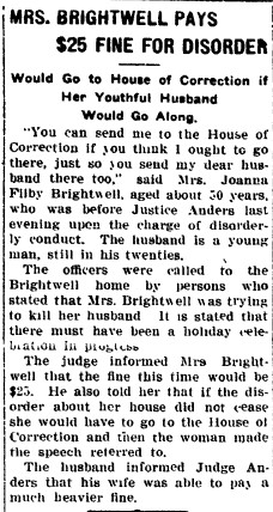

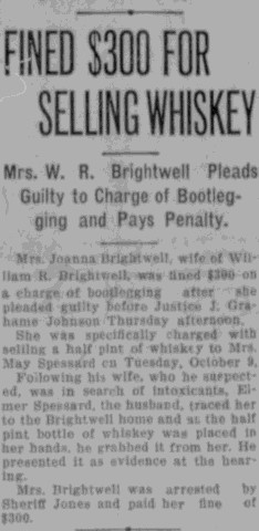

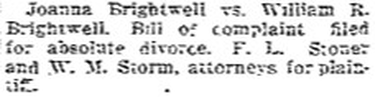

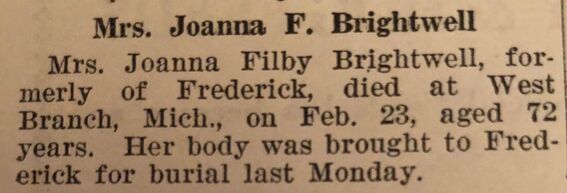

The title of this "Story in Stone" reads like the name of a big-city law firm --Rinaldo & Rashland. However, that couldn't be further from the truth as this contrived moniker has never graced a "hung shingle" in our fair city and is simply the combination of names of two complete strangers buried nearly next to one another in Mount Olivet's mysterious Area M. Fittingly this specific location is also known as "Strangers Row." We seldom know anything about people whom we call "strangers." When researching individuals in this particular sector of the cemetery, I have to be "lawyer-esque" in approach looking extra hard to find out things about my subjects. This includes a careful cross-examination of relatives, residencies and past employments to attempt to paint a better picture of my subject. I may even find out things about their relationship with the law as well. With two names, Rinaldo, a first name, and Rashland, a last name, I immediately had the vision of a law office in mind, and immediately thought of the practice of those in the profession hanging their proverbial "shingles." An online search for an early visual showed me the law office of our fifth US President, James Monroe, whose grandson and other descendants rest in our cemetery. I also thought of the alleged law office of our most famous legal duo in Frederick history annals. These two were not only "in-law," but were also in-laws, more specifically, brothers-in-law. In researching their lives, I had the opportunity to compare and contrast two individuals —one a humble carpenter, and the other a former actor turned lecturer. These two men were not related, and never met one another. They did not reside in the same town, yet they experienced life in the similar time period of history being born immediately after the American Civil War, and surviving into the Roaring 1920s, with one actually making it to the Great Depression. One of our subjects traveled the country in his vocation, while the other may not have ever ventured out of Frederick County or Maryland to my knowledge. One worked with talented hands wielding tools, while the other had a mouth and tongue that paid the bills by way of words, verse and prose as his work accoutrements. Both encountered life struggles --one had financial woes, while the other had problems with alcoholism. Each died suddenly, and not in the confines of one's own home or a hospital room. Their surprising deaths made headlines in the local newspaper while likely talked about by countless local residents not knowing either decedent personally. Last of all, neither subject had funds of family to purchase them a proper grave space. Charity led them to their respective, final resting places in Frederick's Mount Olivet Cemetery and not elsewhere. Now, permit me tell you the stories of Rinaldo & Rashland. Rinaldo C. Walters He was born on February 28th, 1868 and given a masculine Italian name (with German and Latin roots) which crudely translates to "wise power." Rinaldo was born in West Virginia, the oldest of six children to parents John Wesley Walters (1833-1916) and Annie Cecelia Pampel (1845-1928). Berkeley County was the likely home of Rinaldo's birth and paternal relatives as some records infer. Rinaldo spent his youth in both Frederick City and Shepherdstown, WV. and likely received little advanced schooling. He did, however, learn a trade — that of his father. He would work as a carpenter for the balance of his life, while his maternal uncles (Henry and David Pampel) would make their mark crafting iron instead of wood. The Pampels' father, Frederick (1800-1876), hailed from France and this surname can still be seen on several existing iron grates throughout town. We will look into their story at another time. Rinaldo and his parents would eventually move to Frederick in the early 1900s and lived on West Patrick Street according to an obituary for Rinaldo's youngest sister, Violet, who died in Baltimore at 20 years of age in August, 1908. We also learn from this obit that three other siblings lived in Baltimore at this time (Ira, Eugene and Mary "Mamie"). I also saw records that another brother, Harry, married in Boston and eventually lived in New York City. Violet would be laid to rest in Mount Olivet's Area K/Lot 26. Interestingly, I found two other family members here in a lot where Violet never received a gravestone. Charles L. Walters, an infant nephew of Rinaldo and Violet (and son of brother Ira) had been buried here in February, 1896. Sadly, the child died on his first birthday. Twenty years later, on March 11th, 1916, Rinaldo's father (John W. Walters) would be buried here next to Charles. In the first decade of the twentieth century, Rinaldo is listed as working as a carpenter in a blacksmith operation. This could likely have been the Pampel Foundry, once located on West South Street. Regardless, this would be the last census record I could find for our subject as he was living with his mother at the time at the family home on North Market Street. Meanwhile, Rinaldo's father was residing in the county home at Montevue. In 1915, he is listed as a blacksmith in a Frederick City directory and his exact address was 210 West Patrick Street. Not much else can be found out about Rinaldo. He never married or had children. But, what Rinaldo did have was a drinking problem that included legal intervention from time to time. This comes from reading a few newspaper mentions, in which the issues were related to alcoholism and public drunkenness. From the article below, you can surmise that our subject certainly didn't pick the best location in Frederick to pass out. A newspaper article from 1919 states that Rinaldo was living on East 5th Street. The 1920 US Census backs this claim up by showing Rinaldo as a boarder of widow Jane Renner at 128 East 5th Street. Interestingly, a next door neighbor was William R. Diggs, namesake for the municipal pool located off West All Saints Street and the limousine driver for prominent banker, et. al. Joseph Dill Baker (namesake of Baker Park). By 1928, Rinaldo is back to being called a carpenter in the Frederick City directory and can be found living closer to Diggs Pool than Mr. Diggs, himself, as he was residing as a boarder at 26 West All Saints Street. This would be the year that Rinaldo's mother would pass as well. She is not buried in Area K with her husband, daughter and grandson, but rather in Baltimore where she had lived her final years with a granddaughter. I failed to find our subject in the 1930 census, although he died in 1934. I surmise that he was a patient at the Montevue Hospital located northwest of town on West 4th Street extended towards Yellow Springs on a road destined to hold the name of Rosemont Avenue. This institution was built in 1870 and catered mostly to wayward men giving it the moniker "The Tramp House." One year after the Stock Market Crash of 1929, and ushering in the Great Depression, Montevue served an array of transients including what have been described as "idle vagabond paupers, a recent class of professional vagrants, transients or "tramps" often sought out almshouses like this and jails for temporary room and board." Either by design or heavenly provenance, Rinaldo C. Walters had already found himself here as a resident since around 1928. As you may recall, his father lived his final years at Montevue as well. And here is where our life story ends for a well-marked "stranger" in Mount Olivet's "Strangers Row." Apparently, he was on his way either to, or from, Frederick City, but was found in an adjoining field. My surprise lies in the fact that he was brought to Mount Olivet for burial in a pauper's lot. Perhaps this was dictated by family, as he did receive a gravestone, something his sister and father don't have. I would assume that he would have typically been buried in the "potter's field" at Montevue, a burial ground for hospital residents which we have discussed in an earlier "Story in Stone." Frederick E. Rashland A month ago, I wrote about two other "strangers" in Mount Olivet's Area M that bookend the grave of Robert L. Downing, one of the greatest stars of the theatrical stage in the late 1800s. To Mr. Downing's left, is buried Eli G. Jones, MD (1850-1933). This man practiced for over 50 years, selecting methods he found truly useful from conventional medicine, Physio-medicine, Biochemic, Homeopathic and Botanical (Herbal) medicine. Dr. Jones wrote many excellent articles and books including Cancer: Its Causes, Symptoms and Treatment (originally published in 1922), in which he describes specific and different approaches to each type of cancer then known laying great stress on individualizing the course of treatment for each patient. The story of Dr. Jones directly led me to learn who the decedents were who occupied graves to his immediate left. The nearest grave monument belongs to Rinaldo C. Walters, whom we just chronicled. However, the nearest individual (in a grave) and actually placed beside the mortal remains of Dr. Jones is one Frederick E. Rashland with no marker or monument. I would soon learn that Rashland had an acting career like Robert Downing, but was nowhere near as famous. However, on a smaller stage in the field of education and oratory later in life, Mr. Rashland had quite the reputation that brought many to see and, most particularly, hear him. Funny how a man intent on leaving his mark on communities throughout the country with his talents, is buried in a cemetery without anything to mark and identify his final resting spot and an adventurous life seemingly well-lived. Frederick E. Rashland was born a year and three months before Frederick carpenter Rinaldo C. Walters. This occurred somewhere in New York on November 12th, 1866. I have experienced hardships in trying to find any specific information on this gentleman prior to the 1890s. From later census records, I learned that his father, John Rashland, was a traveling salesman from Baltimore, and his mother was from France. I found City Directories from 1890 and 1895 that show Frederick Rashland as an actor living in Syracuse. My only source of information prior to the US Census of 1900 has been newspapers which further talk of our subject's profession as an actor. The earliest I found was from 1891. In 1894, Fred Rashland starred in the lead role in a comedy play entitled "The Private Secretary." A review of a performance in Hamilton, Ontario specifically called him out for his "grotesque" portrayal. The clipping below introduced me to the woman I would eventually learn to be Rashland's wife. Anita Richards of Perry, New York, was born July 14, 1873 and would go by the stage name of Anita Leslie in her early years as an actress. The couple would marry on August 11th, 1898. Fred's big break seems to have come around the time of his nuptials as he was cast in a play titled "The Air Ship," billed as a farce comedy. This impressive traveling production would play to audiences around the country. I found advertisements of it being performed on stages in the northeast, mid-west and far west including: Anaconda, Montana; Dallas, Oregon; Laramie, Wyoming; Boulder, Colorado; Spokane, Washington; North Platte, Nebraska and Vancouver, British Columbia. This musical may have been prompted by widespread reports of a mysterious airship seen flying over California in Nov-Dec 1896 and throughout the Midwest in April 1897. It was something of a precursor to the UFO sightings of the postwar era, although most of those who saw the airship assumed it was the creation of a human inventor rather than an extra-terrestrial craft. In his blog, Voyages Extraordinaire Scientific Romances from a Bygone Era, Canadian author Cory Gross wrote the following about this particular musical: "Dubbed "a musical farce comedy," it tapped into both the public fascination with powered flight and the Klondike Gold Rush, which were the current affairs of the year. Samuel Langley had just made two successful flights with steam-powered model aircraft in 1896, which flew almost a mile after being launched from a catapult. Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt, became interested in possible military applications and began funding Langely's experiments. Meanwhile, a pair of civilians, Orville and Wilbur Wright, were only a few years off from their historic flight in Kitty Hawk. As the quest for the air was going on, hundreds of thousands of treasure-seekers clawed their way to the Klondike River in the Canadian Yukon Territory in the quest for gold. Unfortunately, by the time stampeding prospectors finally made their way across the treacherous Chilkoot Trail in 1897, most of the good sites had already been claimed. The North West Mounted Police - precursors to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police - acted quickly to ensure a peaceful and orderly gold rush, but hardship and hunger still plagued the Stampeders. Those who could eke out gold from the river bed and the hills became fabulously wealthy. Dawson City came to be called the "Paris of the North" and, practically overnight, the largest city west of Winnipeg." "J. M. Gaites' musical opened with an inventor flying his airship to Alaska and discovering a lake whose shores were literally coated in gold. Sadly his heavy-laden craft went down on the way back, along with all knowledge of the lake's whereabouts. Undaunted, the inventor's nephew decided to try his hand at aeronautical adventure. Reaching Dawson City with a farcical crew of comic characters and buxom beauties, they eventually manage to find the gold and return home in a harrowing thunderstorm. Critics decried what they perceived as a lack of plot, the show being carried by the music, dialogue, and effects. That is a familiar critique even today. Audiences, on the other hand, loved it. After its initial run in New York, The Air Ship went on tour and continued drawing full houses well into the 1910s. Of particular note were the air ship itself flying through the thunderstorm and the wintry scenes in Dawson, many celebrating these as masterful and as realistic as one supposes that a stage play can get. With the advent of The Great War and the widespread use of military aircraft, attitudes towards fanciful flights from before the Wright Brothers changed. Like with Jules Verne and Georges Méliès, the public was no longer interested in Scientific Romanticism. The hard reality of industrialized warfare dashed those aspirations. J.M. Gaites' greatest fame still lay in his future though, writing Vaudeville routines for the Marx Brothers." It seems as if "The Airship" had made its run by the summer 1899, but a few more shows in the Mid-Atlantic region were performed late in the year and early 1900. In the late summer/fall of 1899, Fred Rashland could be found in another production called "The Wyoming Mail." I had found mention of this in respect to a performance in Carlisle, PA, but our subject was well-acquainted with the imagery of the west that this production portrayed as he had recently traveled it. I found the Rashlands the following year in the 1900 US Census in Nettie's hometown of Perry, New York. The two are both listed as actors and living with Mrs. Rashland's parents, Albert and Eleanor Richards. Apparently the two were conducting their own productions that year under "the shingle" of the Rashland-Leslie Theater Company. The brief article below informs the public that the couple were canceling shows for the spring season due to a personal illness experienced by Nettie, but they were not sidelined for long. By 1903, they were traveling together performing benefit shows. One such was called "A Modern Match" and was performed in the greater New York, Pennsylvania and Connecticut region. From exhaustive newspaper research, I noticed a shift beginning in 1909, during a permanent residency in New York City. The twosome are not acting on stage, but Fred Rashland now possesses a Ph. D. and is working for Columbia University, or so say a few articles I read. He seems to be instructing elocution and oratory skills and is held on retainer by neighboring New York and New Jersey public school systems to train students in this fine art. Of particular interest is his inferred work under philanthropist Helen Gould. These lectures kept Fred busy throughout the decade, and into the next. Sadly, this line of work would be responsible for his death. More shocking than that statement is the fact that he would die here in Frederick County! More on that in a moment. In 1920, the Rashlands were living on Mount Vernon Street in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Mr. Rashland's occupation was listed as instructor. I was able to spot the tandem in the 1925 New York State Census. At least in June of that year, they were living in the boarding house of Emma Chapman, a 46 year-old nurse. This was located at 72 Washington in Binghamton, New York. And that brings us to Frederick Rashland's final "curtain call" here in Frederick County. The year was 1926 and the couple were supposedly residing at 100 Third Street in Washington, DC. Lectures and benefit readings were being performed in regional schools in the winter and spring months leading up to the fateful day of May 27th. On this occasion, Mr. Rashland would make an impromptu visit to the Walkersville School and offer his services for a lecture. As you will learn, the performance was never made. Frederick Rashland's visit to Frederick, Maryland would be a permanent one for his mortal remains. As I've said at the outset, he would be buried here at Mount Olivet in Area M. He preceded Rinaldo Walters, Dr. Eli G. Jones and fellow actor Robert L. Downing to the grave. I wonder if he knew Downing at all in the realm of acting? Regardless, I was fascinated with the story of this gentleman, however, I would further learn of two evocative anecdotes involving the seemingly struggling actors. The first involves Nettie's plight in Frederick. It is said that sympathizing friends helped Mrs. Rashland bury her husband in our fair cemetery. "Strangers Row" had been set for that same reason, however very few in this location have back stories like him, and Dr. Jones and Mr. Downing as I have shared. More mimic that of Rinaldo Walters. Mrs. Rashland found herself with no money, and decided to stay. I would learn that she was aided by our local Sisters of the Visitation here in Frederick. I didn't have time to explore this more fully, but I couldn't recall seeing any ties of this couple to the Catholic Church per se, or even religious at all. However, they did appear to be a bit crafty in terms of performing benefits with the seemed end game of benefitting themselves even if it was for daily survival. It seems that Nettie Rashland lived here through the Great Depression era. In 1931, a Frederick City Directory shows her living at the Colonial Hotel at 2 East 2nd Street and working as a waitress. A newspaper article the following year announced that fortunes were about to change for the former actress. Her name would appear on the front page of the Frederick Post. This was quite mind-blowing to me so I decided to go down the rabbit hole and found a follow-up article and the actual patent design in the 1932 edition of the Official Gazette of the US Patent Office. Unfortunately, that's as far as I got with the patent. I couldn't find anything further and don't know if the Visitation Academy received the money or not for Mrs. Rashland's invention of the first non-glare automobile headlights—something all of us certainly appreciate to this day. I could not find Nettie Rashland in the 1940 US Census, but I would learn that she spent the years around that time living at the Montevue Home. I wonder if she knew Rinaldo C. Walters, the man who would be buried next to her husband in 1935? Nettie requested the opportunity to move into a veterans' nursing home for women by proving that she was the daughter of a Civil war veteran. This was in Oxford, New York and was the same home her mother had lived in until her death in 1925. Anita (Richards) Rashland would be accepted for residency at the New York State Relief Corps Home in Oxford. She died four years later at age 75 on September 11th, 1948 and is buried at the New York Veterans Home Cemetery at Oxford in Chenango County. Like her husband, she didn't have to pay for her burial spot either. The last piece of information I "dug up" on this tandem is from a biographical history of citizens of Perry, New York. One such individual written about was Arthur Richards, Mrs. Rashland's father and veteran of the Civil war. I took a moment to read it and an article I had found on the man from a 20th century paper. I was saddened to read a bit about how our acting couple could have been involved in a case of "elder abuse" regarding Mrs. Eleanor Richards after the death of her husband. It reads as follows:  October, 1917 obituary of Albert Richards from Find-a-grave.com from an unidentified Perry, NY newspaper October, 1917 obituary of Albert Richards from Find-a-grave.com from an unidentified Perry, NY newspaper "RICHARDS, Albert - Private. Born 4 June 1832 in Claremont, NH, the son of Edward & Sally (Densmore) Richards. He was married 5 Oct 1854 in Perry, Wyoming Co., NY to Eleanor A. Wilcox, born 26 April 1835 in Warsaw, Wyoming Co., the daughter of Jerome Wilcox. They were married by Eben Francis, a Universalist pastor. Albert enlisted 1 Oct 61 at Perry, NY, a 29 year old Wagoner. Mustered in 7 Dec 61 as an Artificer. In 1862 he accompanied Capt. Lee and his sister on a visit to Bull Run battlefield. While on a scout off Newport Barracks he discovered the sawmill that became so useful to the Battery. Reduced, date not stated. Re-enlisted 1 Jan 64 at Plymouth, NC. Captured 20 April 64 at Plymouth, NC. Held captive at Andersonville, GA, Charleston & Florence, SC. While in Florence he had nothing to eat for three days and had meat to eat only three times during his stay. Paroled from Florence Stockade 10 Dec 64 at Charleston, SC. Arrived 16 Dec 64 at the General Hospital, Annapolis, MD. Sent to St. John's Hospital at Annapolis, MD. Sent home on a furlough. It was at this time he was carried off the train on a pillow - a mere skeleton. Later he returned to the battery when recovered. Transferred 28 May 65 to Battery L, Third NY Artillery. Mustered out 7 July 65. Discharged 17 July 65. After the war Richards lived in Perry and for many years ran the steamer Gypsy carrying picnic parties on Silver Lake. Albert joined the John P. Robinson GAR Post 101 on 21 Aug 1897. His widow Eleanor Richards gave the bulletin board that stands in front of the Universalist church. In later years her daughter, Nettie, married an actor, Frederick Rashland. They came to Perry and took the mother back with them to New York City. It is alleged they were looking for what little money the mother might have. At any rate, the poor little woman was found deserted on a doorstep a few days later by a former Perry boy who saw that she was placed in the Oxford Home where she died a few years later on 10 Aug 1925 at the age of 90. The Richards lived in a little house at 37 Lake St. and is where Mr. Richards died on 16 Oct 1917. Both are buried in Hope Cemetery at Perry." A sad story indeed, but the validity is not proven as far as my research took me. It does hold some credibility however based on the day to day financial struggle of this ever-transient couple to find work for survival, including Fred Rashland's final proposed performance in the Frederick, Maryland vicinity.

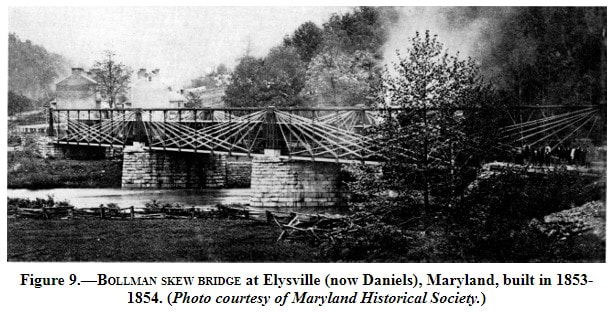

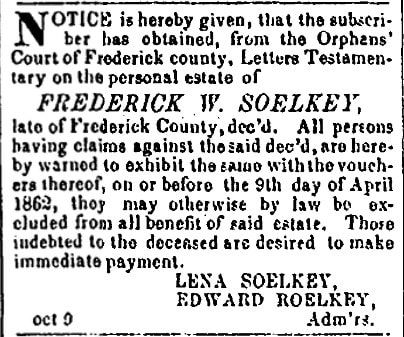

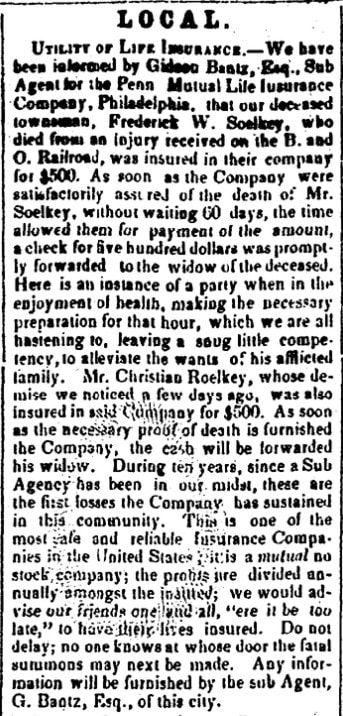

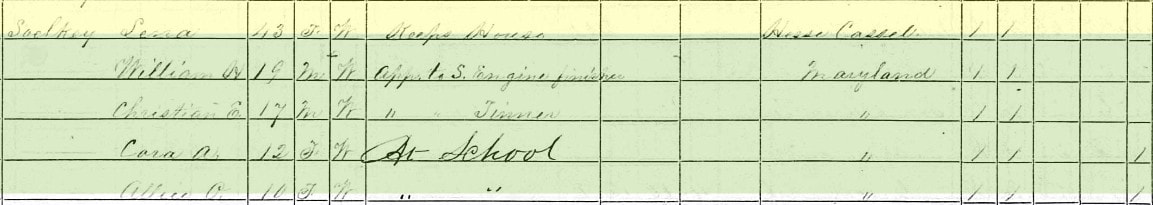

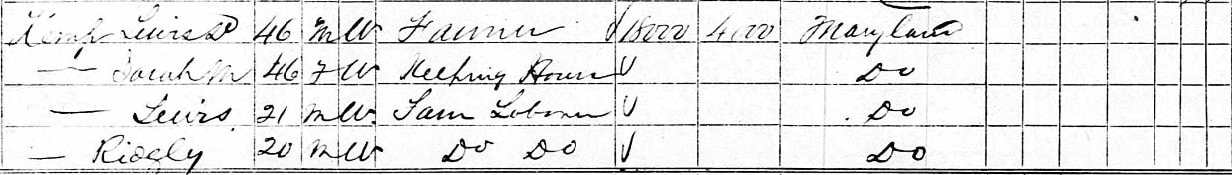

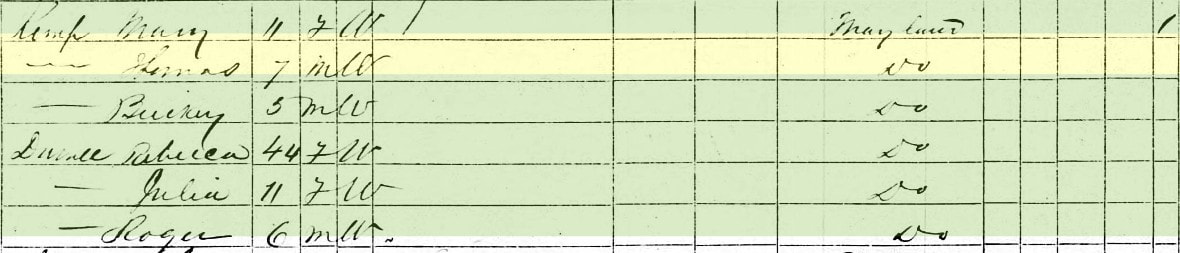

It also speaks to the possible remorse that Nettie felt when her patent for the non-glare automobile headlight was certain to yield a great payout. Maybe that is why she gave the money to those who had helped her in her deepest hour? It would be a decision that would explain why she died penniless and continuing to rely on the charity of others for her residency at our Montevue home, followed by the Oxford Nursing Home, and finally her final resting spot four and a half hours away by vehicle, some 230 miles, from that of her husband's in Mount Olivet. In keeping with our theme about "hanging up shingles," I will leave you with this quote from Italian actress and model Monica Bellucci: “I think the lawyers are such incredible actors. Can you imagine the performance they have to do every day?” This summer, our Friends of Mount Olivet membership group started a project to re-plant our collection of “cradle graves” throughout the cemetery. These unique funerary markers are also known as bedsteads. I wrote a Story in Stone article on these back in October of 2020 entitled “From Cradle to Grave.” A cradle grave consists of a gravestone, a footstone, and two low stone walls connecting them, creating a rectangle designed to hold plantings while memorializing the person buried below. It resembles a bed, with a headboard, footboard with bedrails on each side connecting them. Flowers planted resemble a lovely blanket of color and texture. We have several cradle graves in Mount Olivet, with some marking the graves of children. Popular in the Victorian era, cradle graves were first utilized as early as the 1840s, with most of ours ranging from the 1850s-1870s. Originally, most of these personalized gardens would have been planted and maintained by the family of the deceased. Over the last century, all have been abandoned, in many cases due to families moving away, or dying out. That said, I checked on a few of these cradle graves last month as we were preparing to feature them as part of our programming for Celebrate Frederick’s annual “Beyond the Garden Gates” garden tour. A little bit further out in the cemetery, a double cradle grave was under repair in Area H. It was for two young daughters of Perry Beall McCleery and wife Mary Jane (Doub) McCleery. Here, sisters, Ida Beall McCleery (January 31st, 1854-August 26th, 1854) and Esther Doub McCleery (Feb 25th, 1858-January 25th, 1859) are buried side by side with this twin version of a cradle grave placed above. After taking pictures of this site, I saw a few other monuments of interest just about 30 yards distant to the left and across the lane in neighboring Area G. I was struck by the design of two primary monuments at the front of this family lot belonging to the Bantz and Dukehart families in G/224. These were definitely not cradle graves, but a later “re-boot” on a bed-themed marker over the final resting places of Merle Bowman Bantz (July 3rd, 1850-March 14th, 1899) and Minnie Cecelia Dukehart (March 28th 1860-January 5th, 1906). I was perhaps just reading more into these monuments because I had “beds on my mind” thanks to the cradle grave exploration work I was conducting at the time. Upon closer inspection, these really seemed to “fit the bill” as the old expression goes. No flowers could grow out of these elevated granite markers, however, beautiful hand-carved plant-life is depicted on the face and sides of a faux slanted headboard. My next point of fascination came with the family names here. I was well-acquainted with the Bantz family of Frederick and patriarch Gideon Bantz, Jr.—grandfather of our subject Merle. Gideon Bantz, Sr. was the first president of the Farmers Club of Frederick County which eventually became known as the Frederick Agricultural Society. This is the same group that gives us the Great Frederick Fair each year. Mr. Bantz served as vice president for the first agricultural fair of the society which was held at the Frederick “Hessian Barracks” grounds in the fall of 1853. Gideon Ernest Bantz was born on February 9th, 1792, the son of Henry and Catherine Bantz. He owned farmland both inside, and outside, the town limits, plus a quarry east of Frederick on the National Pike. Bantz was best known for operating a tannery in downtown Frederick on “Brewer’s Alley.” It was positioned north of Carroll Creek along the west side of South Court Street (between the creek and West Patrick Street). Today this location is home to the Citizens Truck Company’s fire station, adjacent the Frederick County Courthouse and its parking lot. In October, 1854 Gideon Bantz found himself serving as acting president of the Frederick County Agricultural Society due to an illness to president Col. Lewis Kemp. This occurred when the Agricultural Society's Board of Trustees met on October 7th, just prior to the opening of their Exhibition on Wednesday, October 11th. Gideon Bantz attended opening day of the fair, but would travel to Baltimore on Thursday the 12th to represent Frederick County by attending the Maryland State Fair. While there, he contracted a sudden illness, blamed on oysters he ate for dinner. Mr. Bantz returned home, but died just 24 hours later stunning the community.  Grave of Gideon Bantz, Sr. (Area G/Lot 188) Grave of Gideon Bantz, Sr. (Area G/Lot 188) Now this Gideon Bantz is buried in Area G, but further down the driveway to the west from Merle and Minnie who I am spotlighting here. He is buried under a very large obelisk across from Confederate Row. However, this plot (where I have found my later bed monument models) was bought by Gideon Bantz, Sr.’s son Gideon Ernest Bantz, Jr., born October 4th, 1813. After his father's death, Gideon Jr. carried on the tanyard and mill business, along with other civic roles in the community. He served as a bridge inspector and spent the American Civil War working with Col. Lewis Steiner (buried close by) under the United States Sanitary Commission. Gideon Ernest Bantz, Jr. apparently died quite suddenly like his father. This occurred on July 21st, 1887 here in Frederick. Heart disease, not oysters, was found as the culprit for his demise. That brings us to Merle Bowman Bantz and Minnie. At first glance, I assumed that Minnie was Merle's wife and this is what brought the Bantz and Dukehart families together in this burial plot. I would soon learn that I was mistaken. As stated earlier, Merle was born July 3rd, 1850. He grew up in Frederick, the son of the fore-mentioned Gideon Ernest Bantz, Jr. and wife Julia Ann (Hartman) Bantz. As a young man, Merle attended the Frederick Academy here in Frederick. Around the year 1869, he re-located to Winchester, Virginia to assist his brother Theodore Marion Bantz in a mercantile business. T. Marion was a free-lance journalist who was very interested in politics and ran what has been called the oldest shoe establishment in Winchester at 14 N. Loudoun Street. He was a very close friend of Charles Broadway Rouss, a Woodsboro (MD) native who spent his formative years in Winchester and made it big in New York City to become a wealthy merchant. Their personal friendship made the Bantz family very popular in Winchester. Another brother, Julius Alton Bantz (1853-1920), would also help with the shoe store. In Winchester, Merle would help grow the family shoe business while his older brother served in other civic and political capacities. Like that of his father and grandfather, Merle's death came as a surprise and shock to his community of Winchester, as well of his old hometown of Frederick. He was a victim of spinal meningitis and died an excruciating death at the age of of 48. This occurred on March 14th, 1899. Merle Bowman Bantz' body would be brought back to his father’s grave plot where he is buried near his parents and other relatives including his brother Julius. I learned that his brother Theodore Marion Bantz is buried about a hundred fifty yards away in Area R. The Dukeharts Until I read Merle Bantz' obituary, I thought he married Minnie C. Dukehart because the beautiful monuments are identical. I was also confused in figuring out family members because a neighboring gravestone in this plot belongs to Merle’s aunt Julia Ada (Bantz) Dukehart, sister to his father (Gideon, Jr.) and Gideon Sr.’s only daughter. Julia, born in Shrewsbury, Pennsylvania, married a fellow named Capt. John Peck Dukehart of Baltimore. (More on him later as he has an interesting story as well). Anyway, Minnie Cecelia Dukehart is the daughter of Capt. Dukehart and the former Julia Ada Bantz, making her Merle’s first cousin. As I’ve said before, I had no judgment if they had been married, as I know that kind of thing happened regularly back in the day, especially between prominent families. I didn't learn much about Minnie at all through my research attempt. However, I did find her in the 1870 and 1880 census records living in Baltimore. I double-checked our cemetery records and they state that both Merle and Minnie were single. She was living with her mother in the 1900 US Census. Both Merle and her father had passed the previous year (1899), and the 1890 census is not available to check her whereabouts, but it was likely that she was living at home with her folks her whole life. Our co-subject of a bed-like memorial died on January 5th, 1906. She was only 45, and succumbed at her residence in Baltimore at 1406 West Fayette Street. I found Minnie's scant obituary from 1906 with no mention of a husband or children. Julia A. Dukehart had her daughter's mortal remains interred in the family plot in Frederick adjacent her father and grandfather, but next to cousin Merle. I find it interesting that Minnie's mother, Julia Ada (Bantz) Dukehart, employed the same design as Merle's monument. I would even find his marker praised in a Frederick newspaper article a year before Minnie's death. Perhaps she requested or mentioned to her mother that she'd prefer the same for her own grave monument? Minnie’s sister, Julia Bantz Dukehart, died as an infant in 1858 at 2-months old. This child and Minnie's brother, Eugene, are both buried in this plot here as well. I said earlier, I wanted to explain further my findings regarding Capt. John Peck Dukehart, Minnie’s father. He was a native of Baltimore, born July 31st, 1824, the son of an early Baltimore insurance agent named John Dukehart. I found John and wife Ann Dukehart in the folds of Baltimore’s Quaker Church. Capt. Peck was raised in the Society of Friends, along with his sister Sarah. I noted that the family also made frequent trips to Columbiana, Ohio in his youth but I could not establish exactly why. In the 1850 census, I found 25 year-old John Peck Dukehart employed as a hose maker. In subsequent censuses he would work for the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. As a conductor, he garnered the respect of both passengers and his colleagues by his actions on the job during a terrible blizzard in 1856. Capt. Dukehart continued working for the railroad until his death on September 27th, 1899. Instead of being buried with his parents in Baltimore, the decedent would be brought to Frederick for burial in the Bantz family plot. Thirty-one years later, Capt. Dukehart’s wife, Julia Ada (Bantz) Dukehart died in Baltimore in December, 1923. This woman had outlived her entire immediate family and had them buried in Frederick's Mount Olivet, all in the same family plot with her parents and siblings. She, too, would join them here in death and would be placed in a grave next to her husband. That pretty much wraps up my review of this plot, entirely influenced by me seeing those bed-shaped markers while observing a cradle grave a short distance away. After writing the piece, I found this article in a local newspaper from 1965 which sheds a little more light on this interesting family of Bantzes and Dukeharts.